Guest post by Katherine Manthorne, The Graduate Center, CUNY

St. Patrick’s Day offers the opportunity to pause and ponder its origins and relations to Irish American art and culture, with special attention to women. In medieval times people in Ireland began to honor the Roman Catholic feast day of St. Patrick on March 17. Closely associated with the festivities, parades were organized, initially not in Ireland but in North America: in 1601 in the then-Spanish colonial town of St. Augustine Florida. By the time of the American Revolution, homesick Irish soldiers serving in the English military marched in New York City to honor their patron saint and the ritual grew from there. In 1848, several New York Irish Aid societies decided to cojoin their parades into one official New York City St. Patrick’s Day Parade. These annual events helped consolidate Irish-American identity at a moment of large-scale immigration, but they were emphatically masculine, with men marching in uniform, carrying guns and playing military tunes.

Women’s Rights Movement Convention, 1848

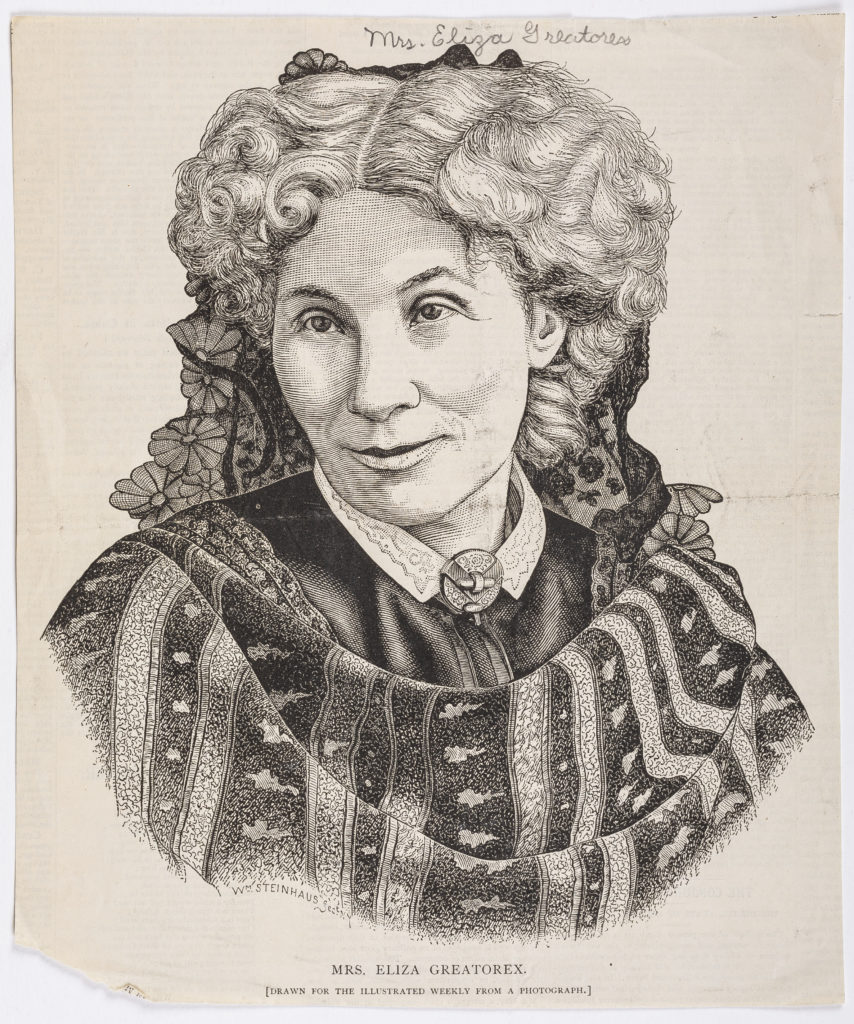

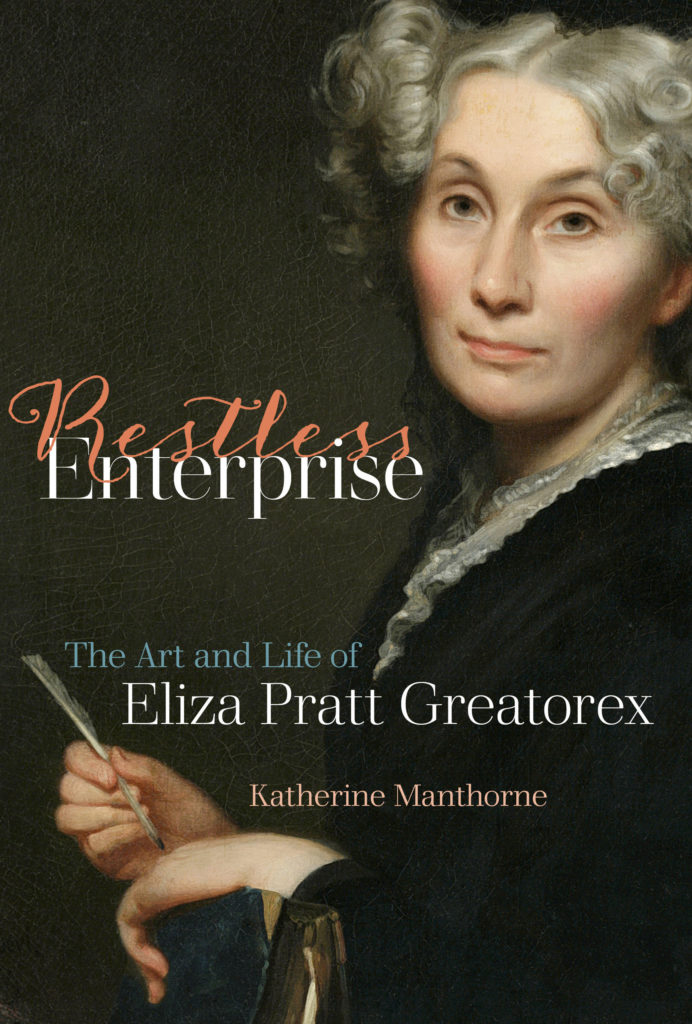

Women were increasingly inserting themselves into public life, signalled by the fact that this consolidated parade was followed just a few months later by the Seneca Falls Women’s Rights Convention organized by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott on July 19 and 20, 1848 near Rochester in upstate New York. Living nearby was the recent émigré from Ireland, who would rise to become the leading woman artist in the New York art world: Eliza Pratt Greatorex (1819–1897; Fig. 1). Pictures she created in the 1860s and 1870s inserted the Celtic presence into the art of her adopted country.

Picturing Landscapes

This daughter of itinerant Methodist minister James Calcott Pratt, Eliza Pratt was in her twenties when she left Ireland, headed for New York and married composer Henry Greatorex (Fig. 2).

There she pursued her art and even as a mother of four was able to paint and exhibit landscapes in the mode of the Hudson River School (Fig. 3).

Rockwell Museum, Corning, NY.

A trip back to Ireland and her mother’s birthplace inspired her Tullylark, Pettigo, Ireland (Fig. 4), which she exhibited at New York’s National Academy of Design in 1860 as Homestead in the North of Ireland.

It depicts a two-story home with a thatched roof nestled on the hillside near Pettigo, the old homestead of her maternal grandparents the Reids. A landscape in the picturesque mode painted in rich greens and browns, it was a heartfelt tribute to her mother. Hanging on the academy walls among scenes ranging from the White Mountains to the Rockies, it helped insert the Irish countryside into the canon of American landscape art.

The Legendary Kate Kearney

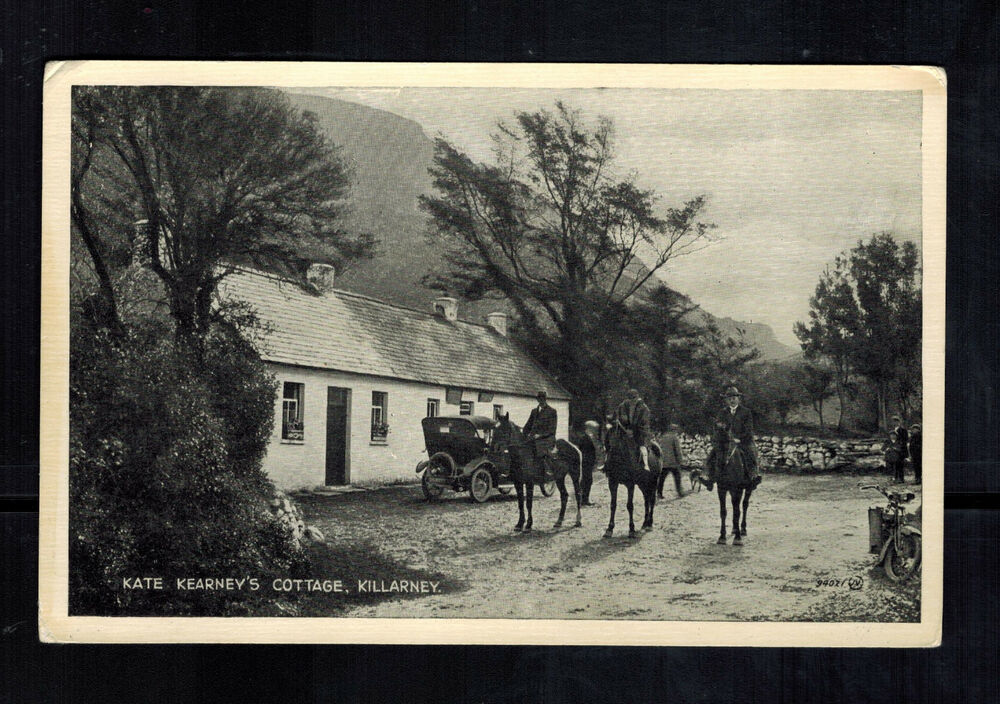

Before the establishment of the Red Cross, the U.S. Sanitary Commission was directly responsible for the Army’s medical care. To raise needed funds, female organizers used a variety of strategies, including mounting fairs. In the Spring of 1864 New York hosted the Metropolitan Sanitary Fair. Artists were invited to show their works, which were sold in a benefit auction. The subject of Greatorex’s submission was telling: Kate Kearney’s Cottage on the Banks of Killarney.

The painting itself remains unlocated, but nineteenth-century photographs (Fig. 5) record the appearance of the cottage she depicted where this legendary Irish beauty made her famous poitín. She flaunted the law, dispensing her “fierce and wild” poitín—i.e. illegal moonshine—to weary travelers who were in need of hospitality. The artist’s loan of this picture constituted her assistance to the war effort, and specifically one that referenced the acts of a defiant Irish woman.

Alliance with Irish Patriots

Greatorex found a loyal supporter in the distinguished Irish-America Thomas Addis Emmet (1826–1919), a medical physician and collector of historic images of New York later bequeathed to the New York Public Library. He was the grandson of the Irish patriot Thomas Addis Emmet (1764–1827), who trained first in medicine and then in law and spent four years in prison for leading the failed Irish uprising of 1798. Released on the condition he go into permanent exile, he lived first in Europe and then emigrated to America, where he became “the favorite counselor of New York” and assisted many of the early Irish immigrants in the U.S.

The obelisk-shaped monument to the old rebel Thomas Addis Emmet still stands in the churchyard of St. Paul’s Chapel of Trinity Church in lower Manhattan (Fig. 6), one of the few structures erected to honor an Irishman in nineteenth-century New York.

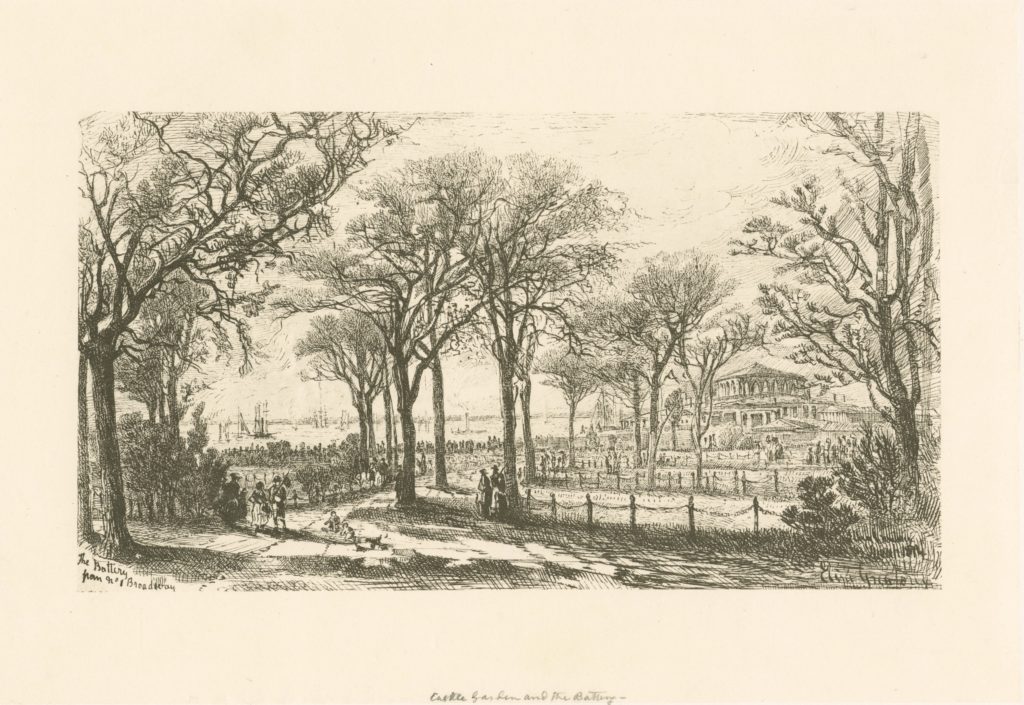

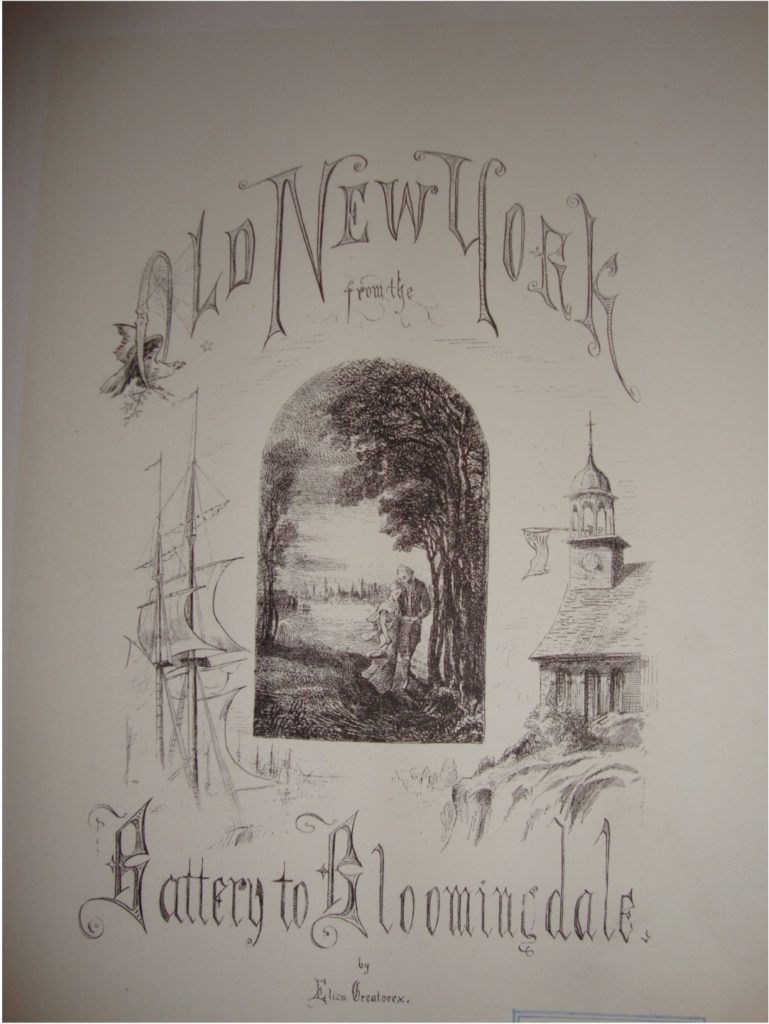

When the artist published her pen and ink drawings of the city’s landmarks in her folio volume Old New York. From the Battery to Bloomingdale (1875; Fig. 7), she honored him by including it. The carving on its façade—combining the American eagle, Irish harp and clasped hands—is an early icon of Irish American unity and a fitting symbol for Greatorex and St. Patrick’s Day.

This text derives from Katherine Manthorne, Restless Enterprise: The Art & Life of Eliza Pratt Greatorex. Oakland: U. of California Press, 2020.

Katherine Manthorne is on the art history faculty at the Graduate Center of City University of New York. She is the winner of numerous fellowships and awards from the Fulbright, Terra Foundation and elsewhere. Researching visual culture of the Americas, she perceives a need to insert more women into that history. Their role in photography is explored in Women in the Dark: Female Photographers in the US, 1850–1900 (Schiffer Publishing, 2020). Her books Restless Enterprise: The Art & Life of Eliza Pratt Greatorex (U. of California Press, 2020) and Fidelia Bridges: Art and Nature (Lund Humphries, 2023) investigate painters and graphic artists.

Other Art Herstory blog posts you might enjoy:

Emma Stebbins, Anne Whitney and Vinnie Ream: American Women Sculptors of the Nineteenth Century, by Maria Ausherman

Women Artists at the Cape Ann Museum, by Erika Gaffney

Illuminating Sarah Cole, by Kristen Marchetti

The Floral Art of Emily Cole, by Erika Gaffney

Defining Moments: Mary Cassatt and Helen McNicoll in 1913, by Julie Nash

Women Reframe American Landscape at the Thomas Cole National Historic Site, by Erika Gaffney

Laura Seymour Hasbrouck, A Painter of the Hudson River School, by Lili Ott

Susie M. Barstow: Redefining the Hudson River School, by Nancy Siegel

The Rich and Complex Character of May Morris, Designer, Embroiderer, Jeweller and Writer, by Thomas Cooper

Marie Spartali Stillman’s The Last Sight of Fiammetta, by Margaretta S. Frederick

Visual Feasts: The Art of Sarah Mapps Douglass, by Erika Piola

Portraying May Alcott Nieriker, by Julia Dabbs

Happy Birthday, Fidelia Bridges! by Katherine Manthorne

Evelyn De Morgan: Painting Truth and Beauty, by Sarah Hardy

The Ongoing Revival of Matilda Browne, American Impressionist, by Alexandra Kiely

Esther Pressoir: Imagining the Modern Woman, by Suzanne Scanlan

Marie Laurencin and the Autonomy of Self-Representation, by Mary Creed

Victorine Meurent, More than a Model, by novelist Drēma Drudge