Guest post by Victor Sande-Aneiros, art historian and graduate of The Warburg Institute

Last month, seventeenth-century Bolognese painter Elisabetta Sirani (1638–1665) received her first solo exhibition outside Italy in New York’s Robert Simon Gallery. It is therefore an opportune moment to revisit an artist widely recognized as one of the most successful professional female artists of her time, but also one who faced particular challenges to her reputation.

Sirani was trained by her artist father, Giovanni Andrea Sirani (1610–1670), in painting, drawing and printmaking. She received early recognition with her first major commission at age 19 [Fig. 1], for a huge multi-figure painting. For this she was paid the same as her male peers. She was accepted as a full professor at the Accademia di San Luca in Rome, a clear recognition of her as a master painter. In 1662, aged 24, she became head of the Sirani family workshop, after the arthritic gout in her father’s hands prevented him from holding a paintbrush. And she established Europe’s first art school for women outside the convent, with at least eleven of her students going on to work as professional artists.

Sirani died unexpectedly at age 27, but throughout her short career she completed more than 200 canvases. Her patrons ranged from religious institutions and merchant families in Bologna to ruling elites in Florence, Mantua and Parma, and royalty from Poland, Savoy and Bavaria.

A threat to Sirani’s reputation

Despite these successes, being a woman in a male-dominated profession was not without its challenges. Sirani faced accusations that she was not the author of her works; that her father allegedly assisted in painting them. Sirani’s family friend, mentor and biographer, Carlo Cesare Malvasia (1616–1693), cites the rumors in his Felsina pittrice: The Lives of Bolognese Painters (1678): “those individuals and malicious people, who would spread that she was helped by her father, who, cunningly, they said, attributed his own things to her, to render them more rare, and admired, as a work by a woman.”

This sort of accusation was not unheard of for female painters. When Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–c.1656) painted Susana and the Elders [Fig. 2], aged just 17, critics also claimed that her artist father, Orazio Gentileschi (1563-1639), must have helped in painting some of it. In Sirani’s case, it seems impossible that her father, with arthritic hands, would have been able to produce work to then attribute to her. Supporting this argument is a letter dated 1662 by Sirani’s patron and agent Marchese Ferdinando Cospi to Prince Leopoldo de’ Medici, in which he assured that “there is no need to suspect that he has helped his daughter in any way [….] her Father being completely disabled.” While we cannot say exactly what prompted the skepticism of Sirani’s authorship, we can get a better idea by looking at what her contemporaries said about her.

Surpassing expectations of female artists

There are some extant letters between agents and patrons which attest to Sirani’s artistic abilities, but the main surviving document for this purpose is Malvasia’s biography. It is helpful that he uses the terminology of Renaissance art criticism, which was inherently gendered as masculine and feminine, with the former always considered superior.

Malvasia’s admiration for Sirani comes through clearly in his repeated reference to her being more like a man than a woman. This was intended as a compliment in an age when women were considered the weak and inferior sex. Within the world of art production, women were thought to have less intellectual, creative and technical capacity than men. Malvasia compares Sirani to the acclaimed classical painter Apelles: “she knew how to emulate on the canvases all the vivid lines of Apelles”. And he goes on to say that her abilities surpassed that of men: “she never worked as a woman, and more than a man” and that she never showed signs “innate in the weak sex.” Malvasia concludes that Sirani “had something virile and of greatness.”

It is in this context of the (gendered) reception of Sirani that we can perhaps account for the suspicions about her abilities. As Fredrika H. Jacobs explains in her seminal Defining the Renaissance “Virtuosa,” when a woman surpassed her own natural abilities as the inferior sex—in this case being likened to men—she was subject to skepticism because of her exceptionalism.

A female history painter

But what qualities in Sirani’s work made her exceptional? Two extraordinary traits mark her work. The first is her specialization in history painting, considered the genre par excellence since Alberti’s treatise on painting, De pictura. Male artists, almost exclusively, pursued this genre, because they were considered to have the capacity for the invenzione (invention) and ingegno (innate talent) required to produce history paintings. Invention was especially considered a sign of the artist’s genius, as it conveyed their ability to conceptualize, reinterpret and re-present classical and biblical stories in ever creative ways. On the other hand, female artists were deemed competent only in imitative works such as portraiture, which was not considered the product of an artist’s genius.

We get a clear sense of Sirani’s inventiveness in her history paintings. These often featured non-eroticized, courageous, intelligent and dignified women, rarely depicted by male painters with positive virtues. The story of Timoclea [Fig. 3], who pushed her rapist down a well and stoned him to death, is one example. Such representations elicited praise from her contemporaries. For instance, the artist Bonaventura Bisi introduced Sirani to the Medici court in a 1658 letter, saying: “she paints like a man with much deftness and invention.”

An exceptionally skilled female painter

The second factor that made Sirani an exception among women artists were her virtuoso technical skills in painting, drawing, wash sketches and etching.

For example, in her Virgin and Child [Fig. 4], she depicts Mary’s clothes with thick and fluid lines, a sign of confident brushwork. The same can be said for her ink wash sketches that rarely show signs of pentimenti, or changes [Fig. 5].

Even her preparatory drawings and sketches in chalk followed by ink wash [Fig. 6] display her deft hand. Malvasia exalts Sirani’s “handling of brushes [that] she seemed so at ease as if playing, rather than painting.”

Such ease of execution was at the time described in the terminology of art criticism by facilitá (effortlessness), disinvoltura (ease), fierezza (quickness) and sprezzatura (non-chalance)—all qualities usually identified in artworks by men. Invention, effortlessness, ease, quickness and nonchalance are qualities that are also evident in Sirani’s compositions, with this example [Figs. 7-8] illustrating the assuredness of her designs. The composition between the original sketch and final painting is almost identical.

Fig. 8. Elisabetta Sirani, Holy Family with St. Anne and St. Joachim, c. 1662; Oil on canvas; Private collection, Milan, Italy.

Malvasia referred to the feracità (boldness) and vivezza (liveliness) of Sirani’s paintings. Other Renaissance art critics described her work as expressing sprezzatura and gagliardezza (vigor). By contrast, Malvasia describes paintings by Sirani’s Bolognese predecessor, portraitist Lavinia Fontana (1552–1614), with tamer words used more commonly to describe artworks by female artists. He characterizes Fontana’s work as leggiadro (elegant), vago colorito (delightfully painted), and di buon maniera (in a fine style).

By attributing typically male artistic qualities to Sirani’s art, her contemporaries elevated her skills as an artist, rendering her an exception among women. And to recap Fredrika H. Jacobs, this exceptionalism may explain why some would doubt that Sirani’s paintings could have been executed by a woman.

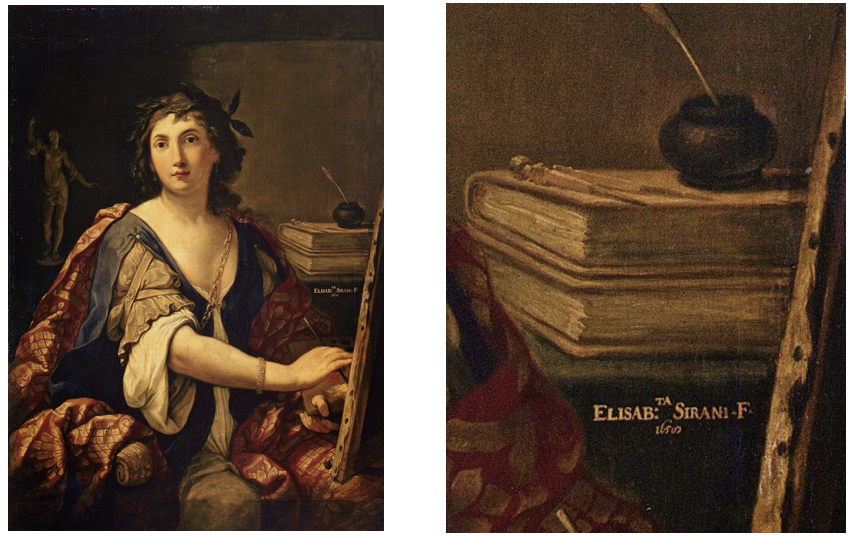

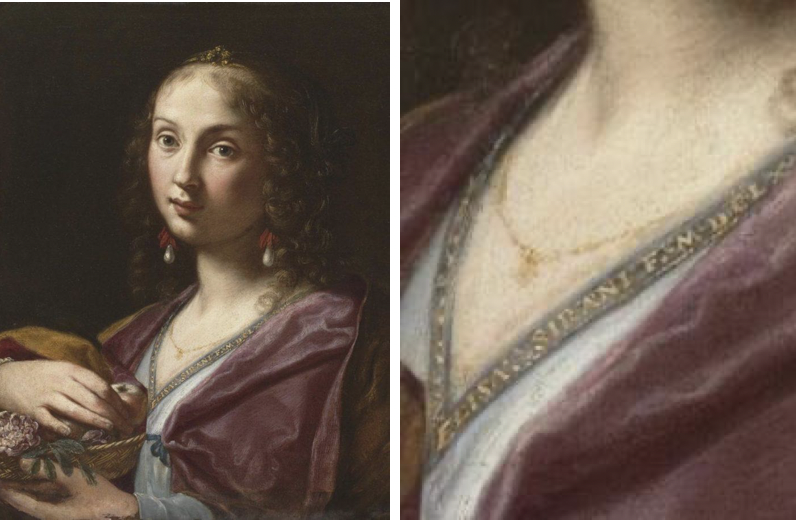

Debunking the rumors

How might Sirani have responded to the skepticism? She engaged in several practices that can be appreciated as attempts to not only forge her artistic career, but also to protect it. Her signing practice, for instance, marked her work as her own. Research by Babette Bohn found that seventy percent of Sirani’s oeuvre featured her signature [Figs. 9-10], while the percentage of signed works by male artists in Bologna did not exceed fifteen percent. Scholars agree that an extensive signing practice attests to a female artist’s objective of achieving recognition for her work in a male-dominated profession.

But Sirani’s signature was not the only way she affirmed her authorship. We know from her biography, archives and her diary, in which she recorded many of her commissions, that she also welcomed visitors to her studio. Generally, research to date about visits to artists’ studios during the Renaissance and Baroque periods is relatively minimal. What we know includes visits by patrician tourists who make a stopover, curious individuals who wish to see an artist’s work, or potential clients and patrons meeting the artist. Additionally, Sirani’s studio was a place for noblewomen to socialize with the artist; Adelina Modesti describes it as a hybrid studio-salon.

Sirani’s open studio undoubtedly allowed her to show off her work and skills to visitors, and researchers have largely understood this practice as self-promotion. But in the context of the skepticism that circulated about Sirani’s authorship, visits to the studio would have served a secondary purpose: disproving the rumors. In allowing visitors to watch her execute the paintings, Modesti justifiably describes Sirani’s painting in public as a career strategy to reassure clients of her authorship.

Seeing is believing

While there is no explicit evidence that Sirani accommodated studio visits in order to debunk rumors or even that it was a conscious pursuit on her part, her diary indicates that this may have indeed been their function.

The text, included in Malvasia’s biography of Sirani, includes only three mentions of her studio visits, but we can assume that she received many more. According to her maidservant Lucia Tolomelli, “many people continually came to see her paint.” One entry refers to a visit by the Duchess of Brunswick, who came “to see me paint, where in her presence I made a one-year-old Cherub, representing Love itself.” Another entry reads: “the Most Serene Grand Prince of Tuscany came to our house to see my paintings, and in his presence I worked [on] a picture of his uncle the Lord Prince Leopoldo […] In the end he ordered a B. V. [Blessed Virgin] for himself.” And her final entry mentions that, “On the occasion of passing through, the Lord Duke of Mirandola came to see my works, and to see me work.”

The words Elisabetta Sirani uses to describe the three visits are revealing on several counts. In all three entries, Sirani refers to the act of her visitors seeing her works and labor: “to see my paintings,” “to see me paint” and “to see my works.” Her choice of words may seem obvious given that, as a painter, paintings are what she produced and paintings are meant to be seen. But the verb to see reminds us of the proverb that “seeing is believing”; that it is only after seeing something that one can believe it to be true. This echos Malvasia’s note that Sirani’s studio visitors “confirmed by seeing.”

A live confirmation of authorship

Reinforcing this idea are Sirani’s diary references to the visitors’ presence: “in his presence I worked [on] a picture” and “in her presence I made.” That her visitors were physically present while Sirani made an artwork, and not only saw her works for themselves but saw her at work, served a strategic purpose. An artist’s signature on a painting establishes their presence; Sirani’s studio visits went a step further by offering visitors a “live” signature, an in-person attestation of her authorship and famed abilities. Arguably then, that this confirmation occurred in visitors’ plain sight rendered the visits an authentication even more reliable than a written or painted signature. And we can safely assume that her open studio practice had a positive effect on Sirani’s reputation, as many of her visitors went on to commission new work.

Victor Sande-Aneiros studied modern languages at Royal Holloway College and art history at The Warburg Institute. He is an emerging art historian aiming to contribute to raising the profile of female artists from the past, with a particular interest in questions around their training, reception, and social and gender history.

More Art Herstory guest posts about Bolognese women artists:

Elisabetta Sirani: Self-Portraits, by Jacqueline Thalmann

Stitching for Virtue: Lavinia Fontana, Elisabetta Sirani, and Textiles in Early Modern Bologna, by Patricia Rocco

Elisabetta Sirani of Bologna (1638–1665), by Adelina Modesti

The Restoration of Royalty: Lavinia Fontana’s Queen of Sheba and King Solomon, by Aoife Brady

Celebrating Bologna’s Women Artists, by Babette Bohn

Drawings by Bolognese Women Artists at Christ Church, Oxford, by Jacqueline Thalmann

Lavinia Fontana and Elisabetta Sirani at the Smith College Art Museum, by Danielle Carrabino

Sister Caterina Vigri (St. Catherine of Bologna) and “Drawing for Devotion,” by Kathleen G. Arthur

Lavinia Fontana: Italy’s First Female Professional Artist, by Elizabeth Lev

An engagingly written piece