Guest post by Isabella Rosner, PhD student at King’s College London

The following is a shortened retelling of an article entitled, “‘A Cunning Skill Did Lurk’: Susanna Perwich and the Mysteries of a Seventeenth-Century Needlework Cabinet,” published in Textile History (volume 49, issue 2, 2018).

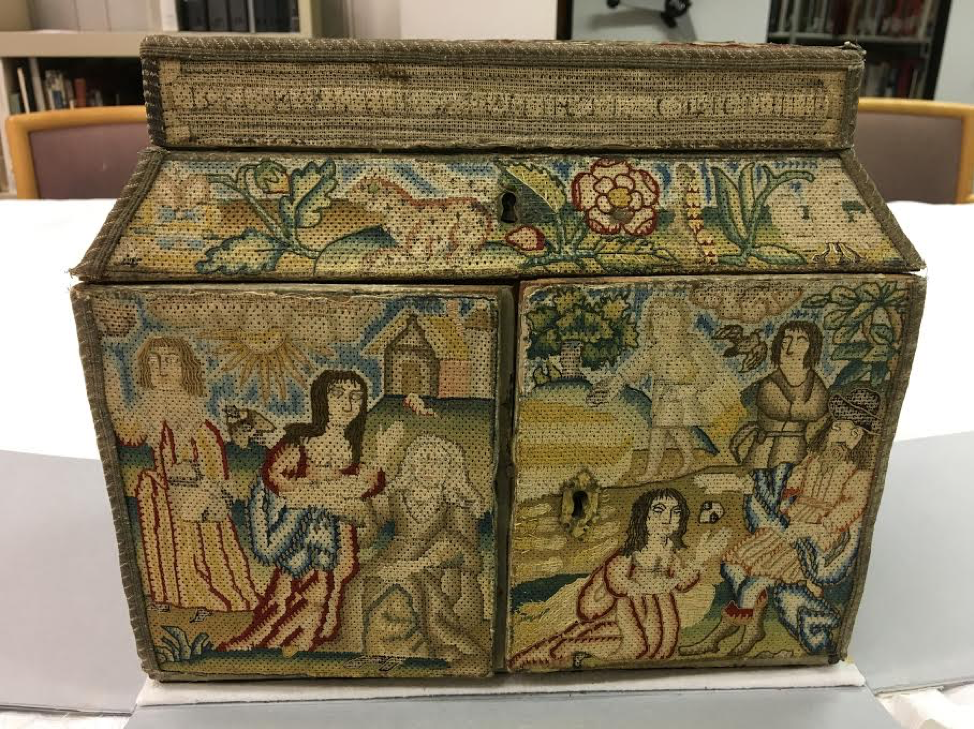

In July 2017, for the first time in nearly 40 years, a seventeenth-century embroidered cabinet in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) was taken out of storage. At first glance, it looks like an ordinary embroidered cabinet of its time, with front-opening doors, interior drawers, and a lid that opens to reveal a large storage tray. But closer inspection reveals a coat of arms on the cabinet’s interior. This cabinet may be the only surviving example with a coat of arms—it is this detail that led me to research this object, made more than 350 years ago. Could this cabinet have been made by Susanna Perwich, a famous early modern English musical virtuoso?

From around 1650 to 1675, many young Englishwomen from wealthy families completed their needlework education by stitching embroidered cabinets and caskets—boxes containing perfume bottles, ink and quills, and, in secret compartments, treasures kept hidden from the wider world. While embroidered caskets have only lids that open, embroidered cabinets open at the lid and via two front doors. The LACMA cabinet’s exterior is embroidered with a Biblical narrative and the interior with floral and other natural imagery.

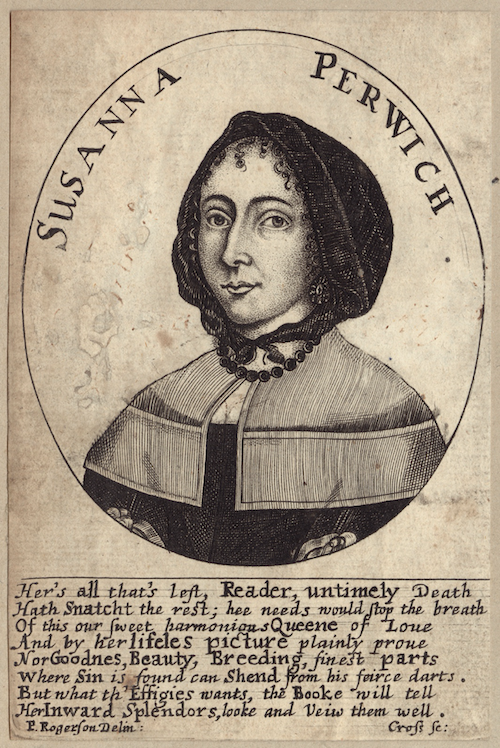

Finding Susanna Perwich

Armorial books list the coat of arms in the LACMA cabinet as those of the Perwiche family. Electronic and print sources yield nothing about a seventeenth-century family called Perwiche, but removing the name’s second “E,” which is reasonable since seventeenth-century spelling lacked consistency, yields relevant results. Most of these relate to Susanna Perwich (1636–1661), a musical prodigy whose life was memorialised in The Virgins Pattern, written by John Batchiler, most likely her brother-in-law. Perwich died at 24 years old from a cold she caught after sleeping on damp sheets in a friend’s home. Batchiler considered her a paragon of feminine skill and virtue, as well as a viol prodigy* and exceptionally talented needleworker.

Susanna Perwich’s parents ran a successful girls’ school in Hackney, a region which was full of girls’ schools in the seventeenth century. The Perwich school, established in 1643, taught girls music, dancing, romance reading, singing, violin lute, harpsicord, calligraphy, accountancy, housewifery, cookery, handicrafts, and embroidery. Susanna became an assistant at the school, teaching courses and leading the orchestra. Given the Perwich school’s emphasis on excellence in typically feminine arts, it is unsurprising that the superb LACMA cabinet is connected to the Perwich family.

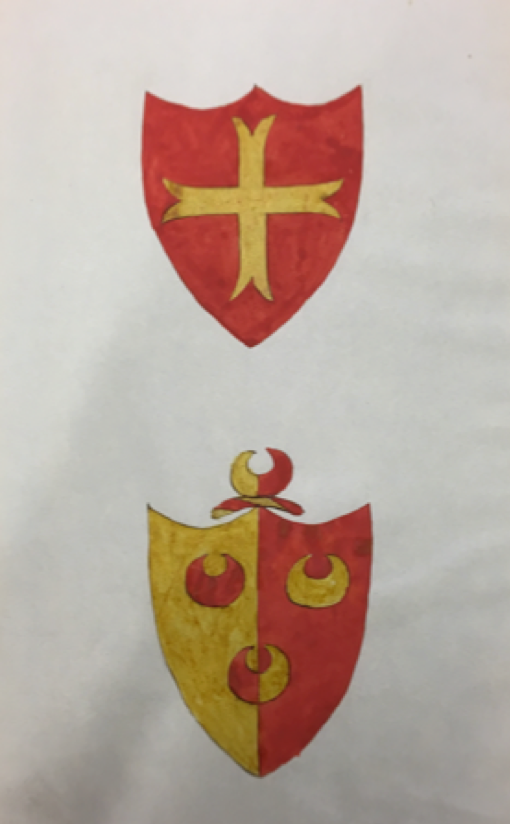

But how do we know the coat of arms in the cabinet belonged to Susanna’s family? There are two substantial branches of the Perwich family, which makes connecting the coat of arms with Susanna’s branch a necessity. A copy of Batchiler’s The Virgins Pattern, handwritten and annotated by someone named M.A. Gliddon in 1843, provides the missing piece of the puzzle. In addition to a note about the family, Gliddon drew two coats of arms, one of which is the exact match of the coat of arms in the LACMA cabinet. Gliddon’s personal annotations proves that the coat of arms belongs to Susanna and her family.

While the cabinet could have been stitched by any of the Perwich daughters, it is likely Susanna’s work because she was renowned for adept stitchery. Batchiler praises her fine needlework in The Virgins Pattern, writing, “She had it at her fingers end,/And lov’d therein fit time to spend./In black-works, white-works, colours all,/That can be found on earths round ball.”

It is clear that Susanna loved stitching. The possibility that LACMA’s cabinet was made by Susanna also helps to explain its survival. While many other examples of needlework were intentionally burned during the Plague of 1665 and unintentionally in the Great Fire of London in 1666, this cabinet survives either through good fortune or because someone cherished and protected it, perhaps because of its creator’s reputation for fine needlework. Somewhere in its history, though, the cabinet’s connection to Susanna Perwich faded: LACMA received it as a gift in 1979 with no information about its previous provenance.

A Closer Look at Susanna’s Cabinet

While Susanna’s renown for skilled needlework suggests that the cabinet is her work, so do the cabinet’s very advanced stitchery, unique Biblical narrative, and inscription. Embroidered cabinets and caskets of this type usually consist of tent, satin, couching, and detached buttonhole stitches, but the exterior of the LACMA cabinet is made up almost entirely of labour-intensive queen stitch. Because it produces large, blocky stitches, queen stitch is usually used for geometric patterns. The cabinet’s maker challenged herself to create recognisable narrative images with a stitch not usually used for that purpose, displaying both creativity and exceptional embroidery skills.

The cabinet’s exterior illustrates the rarely-embroidered story of Ruth, possibly the only cabinet to do so. Ruth’s story covers six panels, beginning on the front doors and moving counterclockwise to the back, up to the cabinet’s top and ending on the right side. The themes of Ruth’s tale are echoed in text stitched onto the cabinet. Circling the top border of the cabinet there is a very faded, now-illegible inscription. Hours of analysis of the cabinet’s inscription eventually revealed that the first words on the front side of the cabinet read, “LORD MAKE THE WOMAN” and three words on the cabinet’s right side read, “AND THE ELDERS.” The inscription is most likely a paraphrased version of a portion of Ruth’s story from the King James Bible.

The interior’s embroidered imagery, with floral and nature scenes and female personifications of the senses, is typical of the period. The female personifications were often accompanied by animals—a stag with Hearing, eagle with Sight, dog with Smell, monkey with Taste, and tortoise or bird with Touch. The interior of the cabinet’s doors features the personifications of Smell and Taste, and in the interior of the lid are Hearing and Touch. Perhaps Susanna, if she indeed embroidered the LACMA cabinet, included personifications of the Senses rather than the Seasons, Elements, or continents that are included on other cabinets and caskets because of her great love of music. As a musical virtuoso, Susanna may have valued sensory experience more than other girls.

A Matching Cabinet?

An embroidered cabinet in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, was quite likely created alongside Susanna’s. Many similarities between the two cabinets indicate that the Fitzwilliam cabinet’s creator went to the same school or was taught by the same teacher as the maker of the LACMA cabinet. The Fitzwilliam cabinet’s exterior displays personifications of the Five Senses, along with Orpheus. While these figures resemble those on the LACMA cabinet, even more striking is the same use of queen stitch across the entire exterior. With the LACMA cabinet and the Fitzwilliam cabinet being perhaps the only two known cabinets to be primarily covered with queen stitch, it is likely that the cabinets’ similarities are not merely coincidental.

The cabinets’ interiors are even more similar. Both have the same arrangements of interior drawers and are adorned with variations on the same designs. Both cabinets feature vases overflowing with grapes, strawberries, peapods, wheat, and flowers, as well as similar hunting scenes and landscapes. While the cabinets’ motifs form different compositions, it is obvious that the same print references were used or that the stitchers were taught to depict the same images in the same way.

A Woman(’s Cabinet) in a Man’s World

How did a woman’s cabinet, a smaller iteration of the cabinets of curiosity so popular in the seventeenth century, compare to its larger counterparts? Although men had cabinets that were similar to women’s embroidered examples in size and function, women’s cabinets were more personal because women stitched them themselves and they contained a much larger proportion of the owners’ possessions, as women owned so few objects in comparison to men. While men had cabinets made for them from opulent, exotic materials, women crafted their cabinets’ exteriors, developing more intimate bonds with their boxes because they spent so many months decorating them. When finished, the cabinets and caskets held personal possessions such as rings, letters, jewels, and keepsakes, items similar to those kept in men’s cabinets. But for women, the contents of these containers represent most of their possessions. The men who owned cabinets owned immense amounts of land, luxury items, and technically their wives; women possessed very little. For women, cabinets represented autonomy and ownership, whereas for men, a cabinet was just one of many possessions.

Most embroidered boxes and much seventeenth-century domestic needlework in general did not survive two catastrophes, the Plague and the Great Fire of London. Embroidered objects were burned to prevent the spread of plague or were lost in the fiery holocaust that consumed London. The LACMA cabinet is a rare survival. The discovery that the cabinet was likely created by Susanna Perwich not only expands our understanding of the world of seventeenth-century girls, but also of Susanna herself. Now, we can catch a glimpse of her not only through The Virgins Pattern, but also through her stitchery. I hope discovering Susanna’s cabinet inspires the rediscovery of innumerable girls through stitch.

*Correction notice: The original post read “violin prodigy.” Thanks to Michael Fleming (see comment below) for alerting us to make this correction.

Isabella Rosner is a Los Angeles born and raised first year PhD student at King’s College London, where she researches and writes about Quaker women’s decorative arts before 1800. Her project focuses specifically on seventeenth-century English needlework and eighteenth-century Philadelphia wax and shellwork. She received her BA from Columbia University and her MPhil from Cambridge University. She specializes in the study of schoolgirl samplers and early modern women’s needlework in addition to hosting the “Sew What?” podcast about historic needlework and the girls and women who stitched. You can find her on social media at @IsabellaRosner and @sewwhatpodcast on Twitter and @historicembroidery and @sewwhatpodcast on Instagram.

Other Art Herstory blog posts you might enjoy:

Finding Catherine Read, by Adam Busciakiewicz

The Lost Works of Susanna Horenbout, Female Artist at the Tudor Court, by Sylvia Barbara Soberton

Susannah Penelope Rosse: Painting for Pleasure in Seventeenth-Century England, by Anna Pratley

Mary Linwood’s Balancing Act, by Heidi A. Strobel

Mary Beale (1633–1699) and the Hubris of Transcription, by Dr. Helen Draper

Angelica Kauffman: Grace and Strength, by Anita Viola Sganzerla

Levina Teerlinc, Illuminator at the Tudor Court, by Louisa Woodville

Susanna Horenbout, Courtier and Artist, by Dr. Kathleen E. Kennedy

The Theatrical Wonders of Jeanne Paquin’s Belle Époque Parisienne, by Julia Westerman

Warp and Weft: Women as Custodians of Jewish Heritage in Italy, by Dr. Anastazja Buttitta

Angelica Kauffman and Mary Moser: Founding Women Artists of the Royal Academy

‘Bright Souls’: A London Exhibition Celebrating Mary Beale, Joan Carlile, and Anne Killigrew, by Dr. Laura Gowing

A small correction (to those who are not interested in the history and practice of 17th-century English music, but very important to those who are) is that there is no evidence that Susanna was, as stated above, a ‘violin prodigy’. She was principally an outstanding player of the viol, which is not a member of the violin family. She was also an excellent player (according to the book cited, which is the sole source of information about her) of the lute, and a singer and composer, with needlework among her many other accomplishments, but the violin is not mentioned.

I very much enjoyed your article, but also wanted to point out a couple of things. at the age of 7, Susanna witnessed her father marrying for second time to Mary Mason in 1643 – the same year as the school was founded. Do you think there is a strong possibility that it was Susanna’s step mother and matriarch of the school that may have embroidered the casket on her marriage into the Perwiche family?

Hi Rosie! Thanks so much for your question (and apologies for just seeing it). That is a possibility, but there are very few examples of cabinets or caskets known to have been worked by adult women. The only known example is that made by Rebecca Stonier Plaisted at the Art Institute of Chicago, and she includes both her and her betrothed’s initials. Chances are it was made by a teenager like Susanna or one of her sisters.