Meeting Spain’s First Professional Female Sculptor

Guest post by Olivia Turner, Curatorial Assistant, Meadows Museum, Dallas

Luisa Roldán in the Seventeenth Century

Luisa Roldán, commonly known as La Roldana, was born in 1652 into her father’s prolific Seville sculpture workshop. Alongside her seven siblings, she honed her artistic practice through the production of large-scale polychrome sculptures, which were (and still are) central to Seville’s religious processions and altarpiece decorations. In 1672, against her father’s wishes, Roldán married fellow artist Luis de los Arcos. While the two remained in Seville for most of the decade, they spent much of the 1680s fulfilling commissions in Cádiz and Málaga alongside Luis’s brother Tomás, who worked as a polychromer to Luisa’s sculptor.

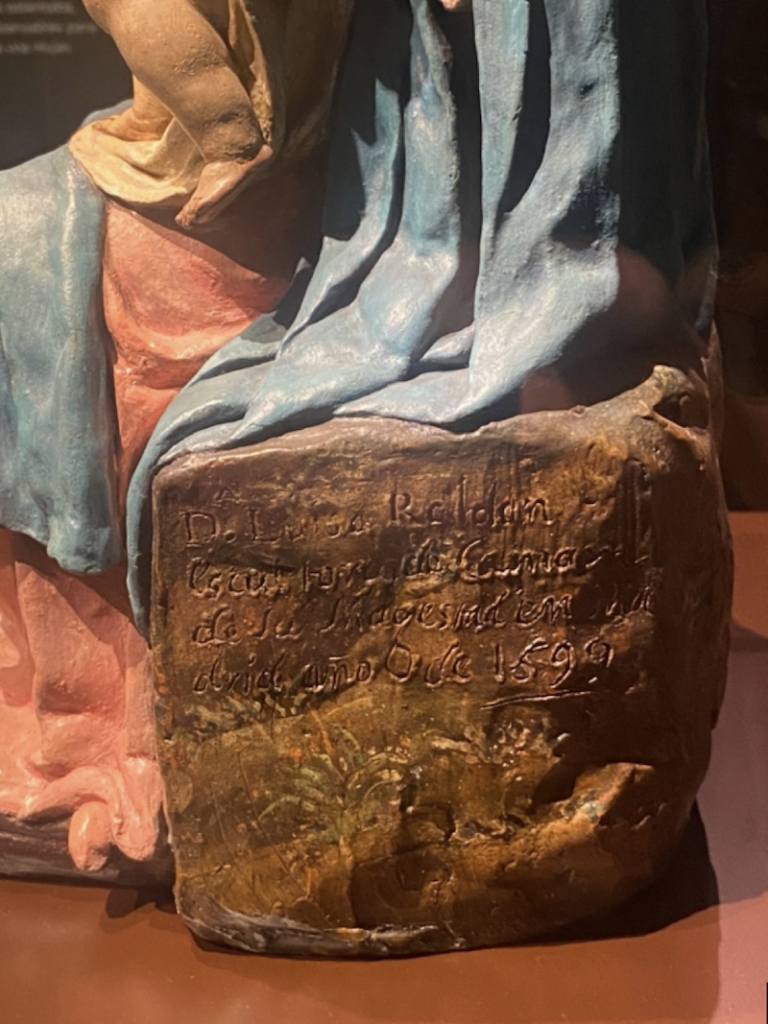

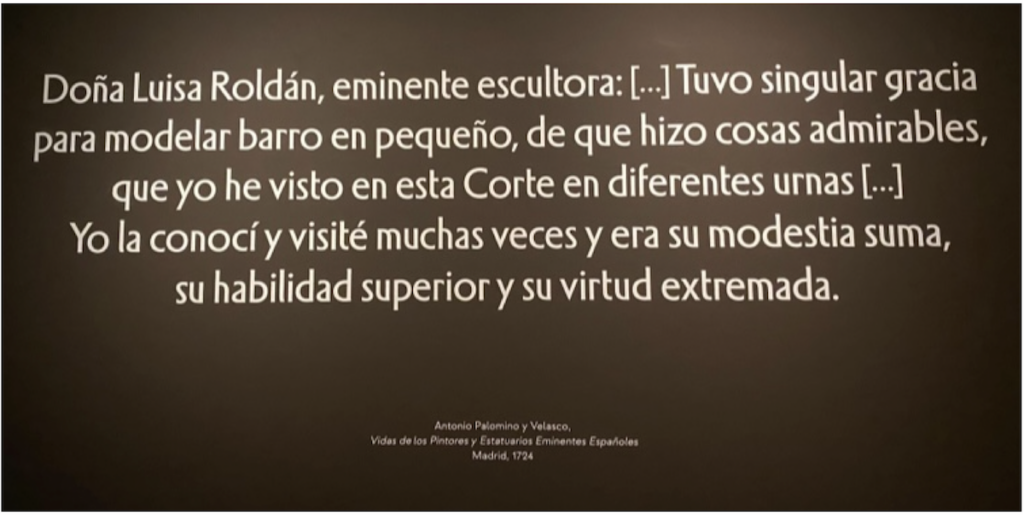

In 1689, Luisa traveled to Madrid, and in 1692 she earned the prestigious title of court sculptor under Charles II, a role she retained under Philip V. Although the Spanish court had hosted other women artists before Roldán—such as Sofonisba Anguissola—she was the first woman to achieve the status of a professional artist. Figures like Anguissola were largely recognized as “ladies in waiting” rather than official court painters or sculptors. During her Madrid years, Roldán shifted from the large-scale polychrome wooden sculptures created primarily for public processions and church displays to small-scale polychrome terracotta sculptures commissioned for private devotion. She was celebrated in her lifetime for her disarmingly lifelike details and the enchanting, whimsical elements that characterize her compositions.

Luisa Roldán Today

Although various international exhibitions have featured her work in recent decades, Luisa Roldán: Escultora Real is the first monographic exhibition of the artist’s work since Roldana, hosted by the Junta de Andalucía in Seville in 2007. The checklist and subsequent research for this show have revealed numerous discoveries over the past 18 years about Roldán’s body of work.

As someone who spends so much time researching an artist who lived over 300 years ago, seeing this exhibition was the closest I have ever felt to meeting her. Luisa Roldán is—thankfully—gaining more recognition, especially with recent acquisitions of her work by institutions such as the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The recent exhibition Making Her Mark, first at the Baltimore Museum of Art and then at the Art Gallery of Ontario, included works by Luisa Roldán. However, Luisa Roldán: Escultora Real makes a powerful statement by dedicating an entire show to Roldán, and if this is the only exhibition of her work I get to see in the next few decades, it will have been entirely worth it. Experiencing this show has profoundly reshaped the way I view the artist, her work, and her legacy—I feel incredibly fortunate to have witnessed it and to share my reflections in this article.

The National Sculpture Museum in Valladolid

This museum houses a diverse collection of two- and three-dimensional objects spanning from the thirteenth to the nineteenth centuries. The majority of these works originate from church and monastery holdings in the Castile region, many of which were confiscated in 1836 by order of the Minister of Finance Juan Álvarez Mendizábal. Additional pieces have entered the collection through donations, deposits, and state acquisitions. For Luisa Roldán: Escultora Real, the museum leveraged its own catalogue—including four sculptures and one large sculptural group by Luisa Roldán—to provide compelling comparanda, or comparative works, in both material and theme.

Sculpting the Sacred: Life and Love in Roldán’s work

Luisa Roldán trained in her father’s Sevillian workshop to produce large-scale polychromed wood sculptures. She designed the works to adorn church altarpieces and take part in the city’s numerous religious processions. The primary objective of these sculptures—and by extension, their artist—was to bring sacred narratives to life, particularly scenes from the Passion featuring Christ and the Virgin Mary.

One of the most striking elements of Luisa Roldán: Escultora Real is the profound sense of life that the artist infused into every inch of her sculptures. Her figures exist in movement, actively engaging with one another. Plants and flowers bloom and wither. Though she sculpts sacred subjects, she does not privilege the Virgin or Christ Child. Every inch, every atom of her compositions is charged with vitality—and, more importantly, with love.

The tension in Christ’s fingers as they gently graze the Virgin’s breast. The putti, burdened by the great responsibility of hoisting the Virgin’s robes, struggling to gather the fabric in their tiny hands (a detail so delicious that it was chosen for the cover of the exhibition catalogue). A young Saint John the Baptist lovingly enclosing the Christ Child’s hand within his own. The small creatures—dogs, lizards, rabbits, and birds—at once transport the viewer to a mystical realm while grounding the scene in naturalism. Even the Virgin’s braid, which takes the shape of an espiga rather than a traditional three-strand plait, is an intentional choice that elevates Roldán’s work beyond mere representation.

In Escultora Real, these sacred figures—so often depicted as distant and untouchable—feel intimately close, their presence nearly tangible.

Pairs, Process, and Partnership

A major theme of the exhibition is the presence of sculptural groups, particularly sculptural pairs. These include San Servando and San Germán, Ángel con corona de espinas and Ángel con los clavos, as well as the two Niño Jesús Nazareno sculptures, among others. This reflects a preference for symmetry in commissions such as altarpieces, which, in turn, creates a striking visual balance within the installation itself. The mirrored compositions enhance the dynamism of the display and offer valuable insight into Roldán’s artistic process, allowing the viewer to imagine what it must have been like for her to work in pairs.

This duality also invites a deeper discussion of Roldán’s career, particularly the relationship between her two primary media: large-scale polychromed wood and small-scale polychromed terracotta. Escultura Real carefully balances these two aspects of her oeuvre, reinforcing the importance of both in her artistic trajectory.

Additionally, the prevalence of sculptural pairings underscores a crucial aspect of artistic production in seventeenth-century Spain. Strict guild regulations mandated a division of labor, requiring a separation between specializations such as sculpting and polychromy. As a result, Roldán collaborated extensively with her brother-in-law, Tomás de los Arcos, who painted many of her sculptures.

Ultimately, Escultora Real highlights how pairings—of figures, materials, and collaborators—defined La Roldana’s career, an idea the exhibition conveys with remarkable clarity.

Material Mastery and Artistic Context

This show not only provides a comprehensive perspective on Luisa Roldán’s oeuvre but also offers deeper insight into the artistic landscape of seventeenth-century Andalusia. Alongside her sculptures, the exhibition presents works from her contemporaries, including her father, Pedro Roldán, as well as Pedro de Mena and José de Mora. Paintings from her father’s frequent collaborator, Juan de Valdés Leal, along with works by Luca Giordano and prints by Francisco Gazán and Alonso de Ortega further enrich the display.

This diverse selection of media not only contextualizes Roldán’s sculptures thematically and aesthetically, but also underscores the extent to which she engaged with the artistic tastes of her time. Furthermore, the inclusion of the National Gallery’s masterfully produced video on the making of the Getty’s San Ginés de la Jara sculpture—displayed in the final gallery—highlights the extraordinary physicality of this craft.

Seeing so many of Roldán’s works assembled in one place, particularly her large-scale polychrome sculptures, prompted me to reflect on what it meant (and still means) to be a female sculptor. The creation of such works required extensive woodworking skills, beginning with large saws to shape the figure’s form, followed by progressively smaller chisels to refine intricate details such as veins, fingernails, and wrinkles. The mastery of this wide array of tools was essential to achieving the remarkable quality that defines her sculptures.

Though this may seem like an obvious consideration, even as someone deeply invested in Roldán’s work, I had never fully contemplated the profound physicality of her artistic process. This realization, made tangible through the extraordinary selection of works on display, is one of the exhibition’s greatest gifts.

Special Moments from the Exhibition and Beyond

Escultura Real, and other nearby installations, presented a series of rare and remarkable moments that enriched my understanding of Luisa Roldán and her artistic legacy.

Encountering the New Acquisition

Seeing the National Sculpture Museum’s newly acquired sculpture, Tránsito de la Magdalena, was particularly special. It closely resembles one of Luisa Roldán’s works in the Hispanic Society Museum and Library, yet distinct differences in execution and detail invite further study and comparison. After having closely followed the announcement acquisition last fall, I was particularly excited to get to see the work in person, and it did not disappoint.

The Conservation Section

The final section of the installation highlighted the conservation of two small-scale sculptures. Mirrors placed beneath these works provided a rare opportunity to examine their undersides, revealing details that would otherwise remain hidden. This innovative display, coupled with a video documenting the conservation process, emphasized both the meticulous craftsmanship behind Roldán’s sculptures and the dedicated efforts required to preserve them.

A Work by María Josefa Roldán

María Josefa Roldán, Luisa’s sister, also trained in their father’s workshop and, like Luisa, married a sculptor, Matías Brunenque, against their father’s wishes. Though she later reconciled with her father and likely collaborated on several sculptural programs with him, only three sculptures are currently attributed to her. One of these, Santo Domingo de Guzmán, is included in Escultura Real, offering a rare glimpse into her artistic contributions as well as the obscurity of the workshop system that confined many women artists in early modern Spain.

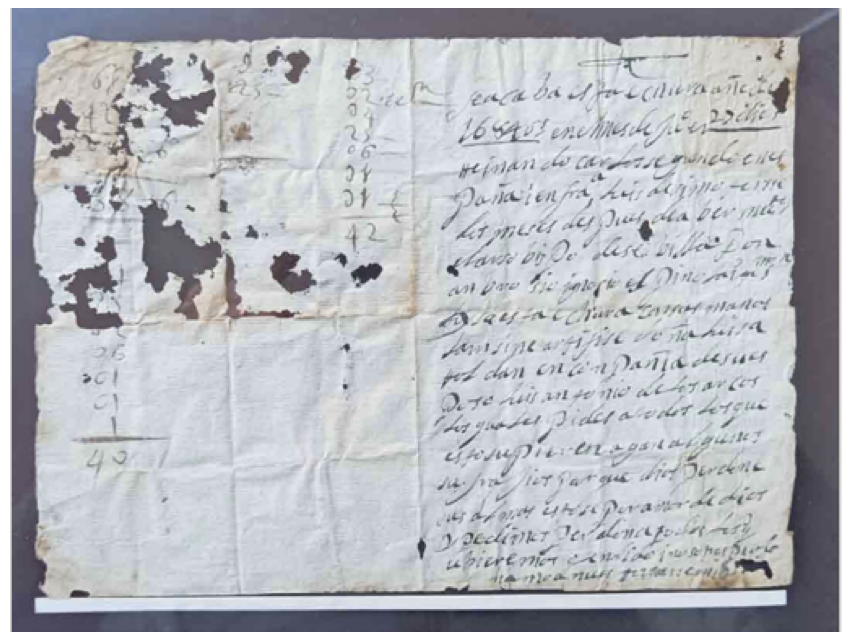

The Autographed Document from Cádiz

This rare document, signed by Luisa Roldán herself and found inside the head of her Ecce Homo sculpture, offered a tangible connection to her life and career, providing valuable insight into her artistic process. Given her craft as a sculptor, seeing her handwriting and even her sketches on paper added a new dimension to my understanding of her artistry, introducing her work to me in a way I had never experienced before.

Two Archangels as an Homage

Escultura Real‘s inclusion of two versions of Archangel Michael served as a fitting homage to Roldán’s own depiction of the subject in the Royal Collection—widely considered her masterpiece. If you are in Madrid, a visit to this sculpture in the newly inaugurated Royal Collection galleries is not to be missed.

A Thoughtful Balance of Sources

The objects on display struck a remarkable balance between works from museums (23), churches (16), and private collections (5), offering a comprehensive view of Roldán’s artistic output and reception. The holdings from private collections were certainly a treat, as it is unlikely they will be reunited in this way again. The opportunity to see them side by side was an extraordinary privilege.

A Tribute to Scholarship

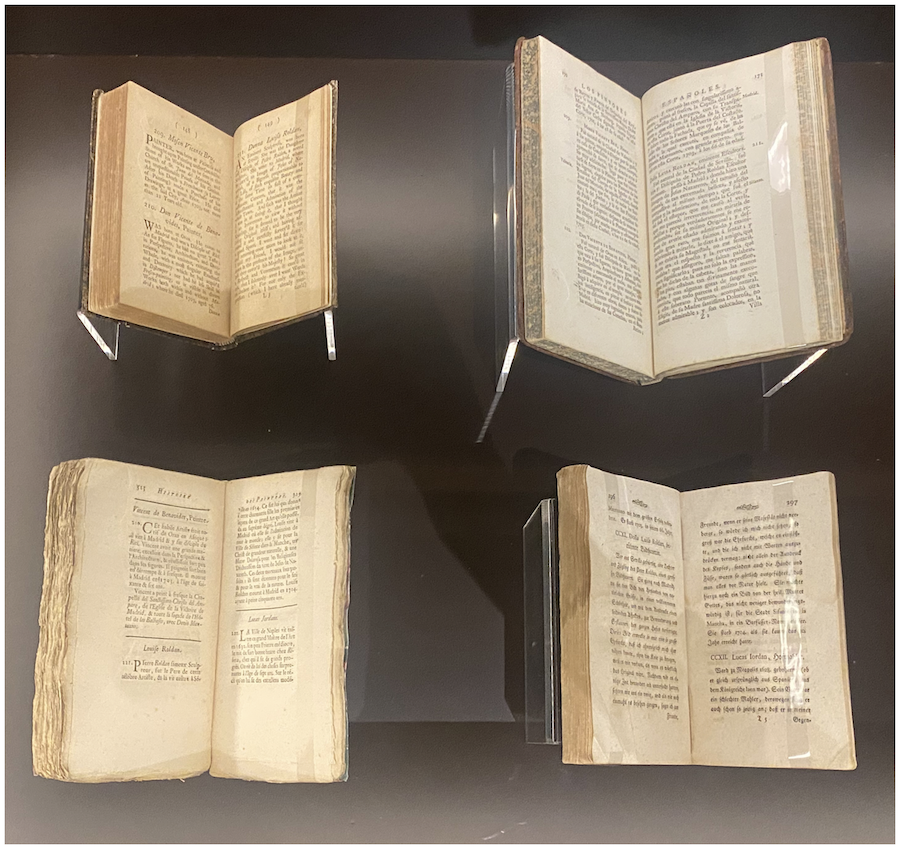

The well-lit section dedicated to secondary sources was a thoughtful addition, especially in its recognition of Elena Amat Calderón’s 1927 doctoral dissertation—the first full-length scholarly assessment of Roldán’s life and work. This acknowledgment of academic contributions highlighted the ongoing dialogue surrounding Roldán’s legacy.

Roldana at the Prado

The outstanding Darse la Mano exhibition features Luisa Roldán’s Christ Child’s First Steps from the Museum of Guadalajara. I wanted to be surprised by the checklist—and surprised I was when I discovered this precious alhaja nestled deep within the exhibition. During my stay in Madrid, I attended the show three times and was delighted to see a small crowd gathered around this brilliant sculpture with each visit.

Each of these moments contributed to a museum experience that was not only visually stunning but also deeply engaging on both an intellectual and emotional level. This exhibition paid a beautiful tribute to Roldán, and it is truly gratifying to see her work so warmly celebrated.

Luisa Roldán: Escultora Real is on at the Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid, until March 9, 2025.

Olivia Turner is the curatorial assistant at the Meadows Museum in Dallas, Texas, and a museum education intern at the Nasher Sculpture Center. She holds a Master’s degree in Art History from the University of Alabama, where her thesis examined the circumstances of women artists in early modern Seville, focusing on the daughters of Seville’s workshops and the career of Luisa Roldán. Olivia’s research interests center on women artists of the early modern period, particularly their roles within religious and cultural contexts. During her time in Dallas, she also completed a graduate certificate in Art Museum Education from the University of North Texas, enhancing her skills in both curatorial practice and museum education.

Art Herstory posts by the same author:

Historic Women Artists in Public Collections: The Kimbell Art Museum, by Olivia Turner

Frida: Beyond the Myth at the Dallas Museum of Art, by Olivia Turner

Other Art Herstory blog posts you might enjoy:

Museum Exhibitions about Historic Women Artists: 2025

Finding Luisa Roldán: A North American road trip, by Cathy Hall-van den Elsen

Reflections on the Audacious Art Activist and Trailblazer Augusta Savage, by Sandy Rattler

A Quiet Eye—The Unique Achievement of Sylvia Shaw Judson, by Rowena Loverance

Rachel Ruysch at Munich’s Alte Pinakothek, by Erika Gaffney

Portrayals of Mary Magdalene by Early Modern Women Artists, by Diane Apostolos-Cappadona

Material Re-Enchantments: A Review of Remedios Varo: Science Fictions, by Suzanne Karr Schmidt

Marie Laurencin: Sapphic Paris, A Review, by Alice M. Rudy Price

Women Artists at the Cape Ann Museum, by Erika Gaffney

Defining Moments: Mary Cassatt and Helen McNicoll in 1913, by Julie Nash