Guest post by Alice M. Rudy Price, Independent scholar

The Barnes Foundation’s new exhibition in Philadelphia, Marie Laurencin: Sapphic Paris, stages an alternate vision of modernism in Paris during the 1920s. Simonetta Fraquelli, consultant curator, and Cindy Kang, curator at the Barnes, emphasize Marie Laurencin (1883–1956)’s distinct aesthetic. They characterize her style as gendered and reflective of a Sapphic sub-culture that developed at salons held by the lesbian writer Natalie Clifford Barney (1876–1972). The exhibit’s layout and palette accentuate subjects and styles that differed from the males in Laurencin’s circle like Georges Braque (1882–1963) and Francis Picabia (1879–1953). Loans from the Musée Marie Laurencin in Tokyo, which has the primary collection of the artist, offer the US visitor an unprecedented depth of experience of Laurencin’s oeuvre. The curators divided the exhibition into seven thematic and partitioned sections, mostly displaying paintings executed between 1911 and World War II.

Entering Laurencin’s World

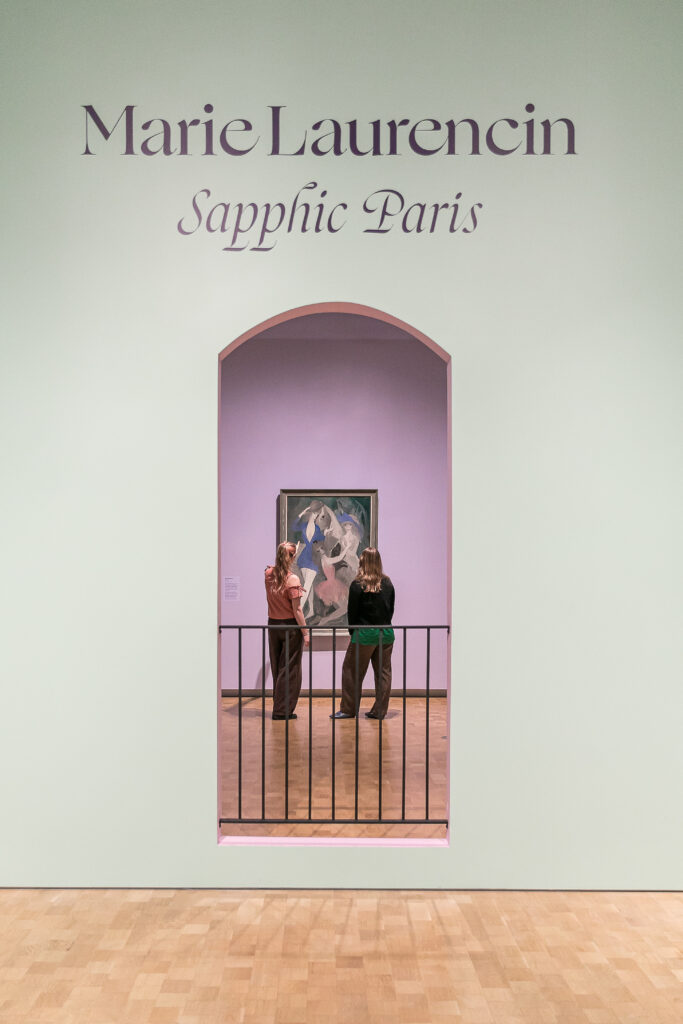

The sage green walls delight the visitor as they enter the Roberts Gallery (fig. 2) and peek through a Parisian balcony window to Laurencin’s Spanish Dancers (1920, fig. 3), hung in a far room on a rosy lavender wall. These installation choices immediately visually characterize her modernity. The exhibit’s colors emphasize the artist’s distinctive use of lightly painted pastels. Later rooms will demonstrate the artist’s sensibility for staging and framing her subjects. The wrought-iron balustrade transports the viewer to the iconic balconies of Paris, where Laurencin began her career.

The offered preview of Spanish Dancers, depicting a close grouping of female dancers, subtly prepares the viewer to take note of Laurencin’s sensitive framing of female relationships. The artist depicts a circle of intimacy, women linked through the touch and gesture of hands. One of the women, identified as Laurencin, wears a short tutu; another a diaphanous dress, nearly the same color as her skin; the third wears a jacket-like garment, fastened only at the waist. The inclusion of the grey dog and a horse also linked Laurencin and Sapphic Paris.

The first room, “Picturing Herself,” introduces Laurencin’s artistic persona through her self-portraits. Many of these date from before 1912, but later works like The Woman-Horse (La femme-cheval) (1918, fig. 4) introduce characteristic themes Laurencin used related to sexual identity, such as hybrid creatures and the inclusion of animals. The gallery text explains that although there is no horse in the composition, in avant-garde Paris at the time, lesbians were associated with Amazons, Greek women warriors who rode on horseback.

The gallery label for the Woman-Horse pointed out that Laurencin “is joined by a gray dog, whose mane matches her own.” This grey dog appears in other canvases, including Spanish Dancers painted a few years later. The label also claims that the blue birds “allude to her romance with the fashion designer Nicole Groult (1887–1967),” but it takes several rooms before a casual visitor will learn more about that relationship. Perhaps more could have been done with the coding of sexuality through references to animals or hybridity, especially for museum goers who lack in-depth knowledge of the Parisian Sapphic subculture. In the catalog, Rachel Silveri develops the reference to the Amazon (pages 124–26). Visitors to the actual exhibit get exposed only to a touch of emergent queer scholarship. Laurencin’s romantic relationships were not limited to women, complicating the concept of a strictly female, lesbian Sapphic circle. These circumstances beg for more overt exposure for viewers to fluid constructions of gender and sexuality.

From “Picturing Herself” the curators move the guests into a room of paintings dating to a period when Laurencin was part of “Picasso’s Gang” in Paris. “In the Thick of It: Paris Before the War” (fig. 6) includes portraits by Laurencin of familiar and unfamiliar personalities from this period: Laurencin’s lover, the poet and critic Guillaume Apollinaire (1880–1918), the poet Marguerite Gillot (d. 1925), and the art dealer Paul Rosenberg (1881–1959). The room also includes several paintings that stylistically intersect with modernism using flattened planes, fragmented elements, and simplified palettes, or take up facets of modern life—like studios, alcohol, or cosmetics—as viewed by a woman. The installation photograph (fig. 7) shows Maison Meublée (1912), with allusions to sex work, hung next to The Elegant Ball, or The Country Dance (1913), a countryside setting where women dance and play instruments, engaging the gaze of the female artist.

Collaborations

The two rooms characterized as “Decoration and Collaboration” demonstrate great creativity and are standouts in the exhibition experience. These arrangements also convey a nuanced and interdisciplinary understanding of cubism and modernism in the 1910s. One section is dedicated to interiors and located adjacent to the large room dedicated to Paris before the War. The curators constructed a model room based on photographs of the Maison Cubiste (Cubist House), a collaborative installation at the Paris 1912 Salon d’Automne (fig. 8).

Kang and Fraquelli’s installation centers Laurencin in the cubist discourse in Paris through her association with an iconic avant-garde project. The presentation of the room with relevant furniture designs expands the concept of modernism into three dimensions and applies it to the appearance of a sitting room, a traditionally feminine space. Flatness, as seen in the paintings by Jean Metzinger (1883–1956) and by Laurencin, was a central concern of cubists, who broke down three-dimensional objects into planes on their canvas. The Maison Cubiste receives little attention in the art history canon, but it reveals the movement as more multi-faceted and intermedial than has been traditionally understood.

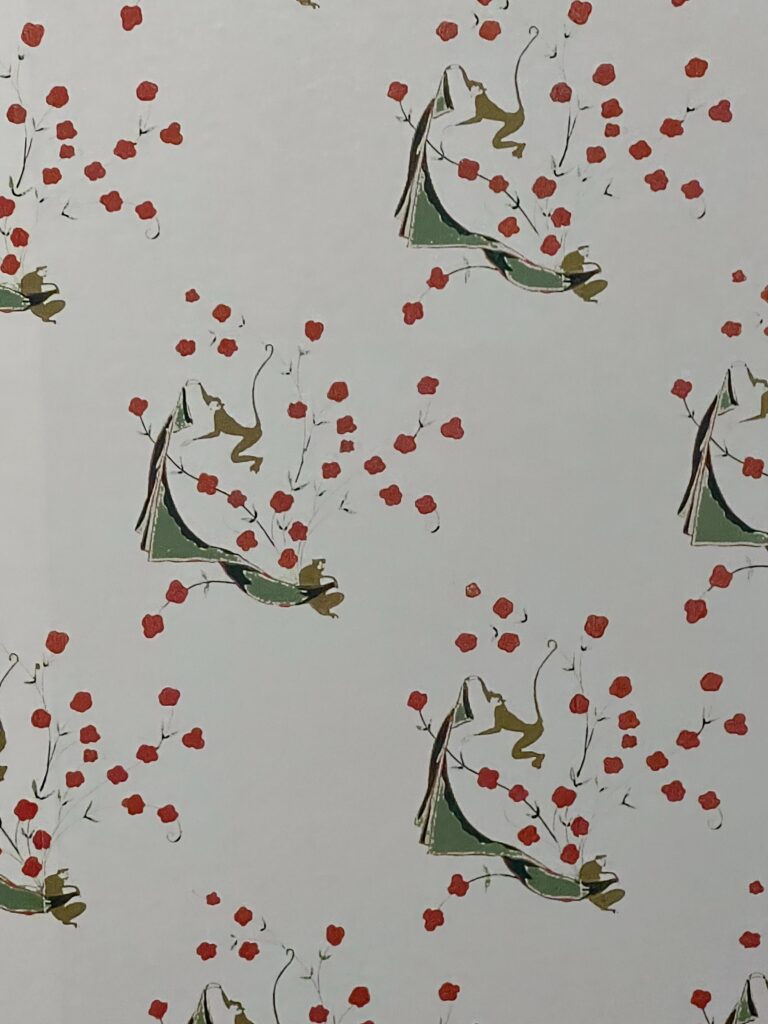

Particularly striking, the Barnes Foundation reproduced wallpaper from a 1912 Laurencin design (fig. 9) that activates the wall surface. The curators told the press in their preview that Gertrude Stein (1872–1946) bought several rolls; interestingly, this was the only reference in the exhibit to Stein, one of Laurencin’s first patrons (see Mary Creed, “Marie Laurencin and the Autonomy of Self-Representation,” 2022).

Turning the corner, the visitor encounters another highlight, a large four-panel screen from 1932, What do Young Women Dream Of? (Figure 10). Unlike the works from the 1910s, Laurencin applied the paint thickly in this decorative work commissioned for the home of her close friend Nicole Groult and her husband André.

For this viewer, the room dedicated to Laurencin’s costumes (fig. 11), sets, and curtain for Ballets Russe’s 1924 production of Les biches (The Does) proved another climax of the exhibition. The section offers one of the clearest demonstrations of Laurencin’s visualization of same-sex desire intersecting with the creation of the modern (fig. 12).

The curators included reconstructed costumes, video excerpts, music, and sketches, which helped to bring Les biches to life. It will also be exciting to see Horse Woman: Making a World of One’s Own, a new performance inspired by Laurencin’s life and work, presented by Headlong Dance Theater in collaboration the Barnes. There will be two open rehearsals, on November 18 and December 15, free with admission; and a final performance and panel discussion on January 18, 2024.

Women among Women

The final sections, “Women Supporting Women” and “Sapphic Modernity” foreground Laurencin’s depictions that reference the groups and networks of women who made up the Sapphic subculture. As the Barnes wall text claims in the section “Sapphic Modernity (fig. 13),” the artist’s oeuvre over her lifetime “demonstrated that to be queer in the early twentieth century was to be modern.” Silveri makes the same assertion in her catalogue essay, “No Modernism without Marie Laurencin: Picturing Queer Femininity (124).” The gallery labels helpfully point out depicted signifiers and symbols that were meaningful amongst Laurencin’s circles. Unlike the previous rooms, the selected works and explanatory texts omit men; these rooms show an exclusively and overtly feminine world. There are more overt references to the Sapphic subculture, including Poèmes de Sapho (Poems by Sappho), translated by Édith de Beaumont, illustrated with twenty-three etchings by Laurencin. The later rooms also demonstrate an evolution of Laurencin’s painting style.

What is Sapphic Modernism?

In the exhibition, at least one visitor expressed confusion at how Laurencin’s works could be construed as modern, implying that viewers needed explicit help to construct a fluid, broad, and inclusive definition of modernism. The exhibition didactics emphasize the shared formal elements of modernism leading to abstraction, without quite articulating the inadequacy of the term “modernism” for artists like Laurencin whose innovative art and idiosyncratic palette express feminine desire, subjectivity, and intimacy. Another viewer stated frustration at a lack of clarity in how the terms “lesbian” and “queer” were used. These complaints may stem from the curatorial decision to minimize wall and gallery text. Possibly the Barnes Foundation also wanted to avoid offending or alienating audiences who are not comfortable with cultural expressions of nonbinary sexual identities. Perhaps walking the exhibition in reverse order, starting with “Sapphic Modernity” and working back to “Picasso’s Gang,” might have offset these criticisms. Surely, visitors looking for more information on Sapphic modernism should make use of the interactive text accessible through QR codes—via the Barnes Focus platform—throughout the exhibition. These texts, written by assistant curator, Corrine Chong, provide useful additional context and are worth the extra time and effort.

The pastel walls in this Barnes installation contrast with the Barnes Foundation’s traditionally neutral choices for wall colors in comparable exhibitions. For example, Picasso: The Great War, Exhibition and Change (2016) featured mostly taupe walls; and for last year’s Modigliani: Up Close (2022–23) the background was mostly grey. The color choices in the present show correspond to Laurencin’s palette and the curatorial intent to visualize an alternate feminine modernism. However, since The Barnes’ version of Suzanne Valadon: Model, Painter, Rebel (2021–22) had walls painted in a similar green, it may be important to address directly the association of the feminine with pastel colors in future exhibits of modernist women.

Conclusion

Overall, this is a refreshing exhibition. The curators offer a different aesthetic from a typical modernist exhibition. Kang and Fraquelli shift the focus on modernist Paris from a narrative centered on the male proponents of cubism and related movements to make clear to readers that theirs was not an exclusive gaze in Paris at this time. The Barnes show breaks new ground. Few, if any, Philadelphia exhibitions that are historical in focus have centered on lesbian or queer expressions of feminine desire.

For more on Sapphic modernity, see J. Winning, The Sapphist in the City: Lesbian Modernist Paris and Sapphic Modernity in Sapphic Modernities, edited by L. Doan and J. Garrity.

Marie Laurencin: Sapphic Paris is on at The Barnes in Philadelphia through January 21, 2024.

Alice M. Rudy Price received a Ph.D. in art history from Temple University, Tyler School of Art and Architecture. Price and Emily C. Burns are the editors of Mapping Impressionist Painting in a Transnational Context (Routledge, 2021). Burns and Price are under contract for their next collaboration, Routledge Companion to Art and Empire, due out in 2024. Price’s dissertation on the Danish artist, Anna Ancher (1859–1935), addressed the artist in relation to the intersecting cultural contexts of rural Denmark, the Skagen Art Colony, Copenhagen and Paris. Her larger project considers the visibility and invisibility of the aging woman’s body in modernist discourse, partnering with Ribe Art Museum and the Skovgaard Museum for an exhibition in Denmark and the US in 2026–2027. Recent projects also address local and identity externalities related to the age of empire.

Dr. Price, an adjunct instructor, teaches the history of art and architecture at Tyler, LaSalle University, and Jefferson University. Price also holds Masters degrees in education and history.

More Art Herstory guest posts by Alice M. Rudy Price:

Modern Women Artists in Copenhagen 2024–2025: Three Exhibitions

Anna Ancher’s Vaccination and Scientific Motherhood

Other Art Herstory blog posts you might enjoy:

Unpacking the Exhibition: Blanche Hoschedé-Monet in the Light, by Haley S. Pierce

Charlotte Eustache Sophie de Fuligny-Damas, Marquise de Grollier, by David Pullins

Frida: Beyond the Myth at the Dallas Museum of Art, by Olivia Turner

Women Artists at the Cape Ann Museum, by Erika Gaffney

Making Her Mark, An Essential Corrective in the History of Art, by Chadd Scott

Carlotta Gargalli 1788–1840: “The Elisabetta Sirani of the Day,” by Alessandra Masu

Reflections on Making Her Mark at the Baltimore Museum of Art, by Erika Gaffney

Masters and Sisters in Arts, by Jitske Jasperse

Marie Laurencin and the Autonomy of Self-Representation, by Mary Creed

Esther Pressoir: Imagining the Modern Woman, by Suzanne Scanlan

The Many Faces of Suzanne Valadon, by Suzanne Singletary

Victorine Meurent, More than a Model, by Drēma Drudge

The Theatrical Wonders of Jeanne Paquin’s Belle Époque Parisienne, by Julia Westerman

The Rich and Complex Character of May Morris, Designer, Embroiderer, Jeweller and Writer, by Thomas Cooper

Material Re-Enchantments: A Review of Remedios Varo: Science Fictions, by Suzanne Karr Schmidt

Anna Ancher’s Vaccination and Scientific Motherhood, by Alice M. Rudy Price

Evelyn De Morgan: Painting Truth and Beauty, by Sarah Hardy

The Ongoing Revival of Matilda Browne, American Impressionist, by Alexandra Kiely

Anna Boberg: Artist, Wife, Polar Explorer, by Isabelle Gapp