Guest post by Alice M. Rudy Price, Independent scholar

In late 2024, two of Copenhagen’s important museums offered three exciting exhibitions that celebrated the art, modernity, and praxis of a pioneering Nordic women artists in the late nineteenth to early twentieth centuries. If you were fortunate enough to be in the Danish capital at the start of its Christmas season, you could see all three in a single day, having only to walk across the park that connects Den Hirschsprungske Samling (The Hirschsprung Collection) with the Statens Museum for Kunst (SMK, The National Museum of Art).

“Women Visualizing the Modern” at the Hirschsprung Collection

The Hirschsprung Collection’s Women Visualizing the Modern. Danish Art 1880–1910 (Kvindernes moderne gennembrud. Dansk kunst 1880–1910), curated by Lene Bøgh Rønberg (Hirschsprung) and Inge Lise Mogensen Bech (Randers Kunstmuseum) offered a provocative glimpse into how 23 Danish painters made modernity evident in their careers and in their canvases (figure 1). Each woman achieved renown during their lifetime, but most are forgotten today. The scholarship here is impeccable, the exhibition well-conceived. The presentation added both dimension and depth to our understanding of modernity as experienced and visualized by women in Denmark between 1870 and 1910. And it showcased works of art by significant artistic pioneers.

The exhibition proved especially successful in its didactic role, filling voids in scholarship and expanding the canon of artists. As the exhibition graphics made clear, the lack of written texts or academic sources on these artists required creative research. The curatorial team culled newspaper archives for obituaries and early publicity resulted in scores of unsolicited letters and messages from owners offering to loan heretofore unknown, but clearly suitable works. Introducing didactic texts without detracting from the strength of the exhibited paintings was a significant curatorial challenge. The organizers cleverly introduced the artists using biographical posters arranged around the perimeter of the central entrance foyer. They positioned the introductory text at the height of a coffee table in the room’s center (figure 2).

Curatorial Innovations

Additionally, the design team installed effectively arranged interactive reading tables including photographs, quotations, facsimiles of handwritten letters, and extracts of periodicals and minutes of the Danish Women’s Society (figure 3).

The curatorial selections and arrangement in the main rooms helped viewers notice subtle relationships and understand visual clues that demonstrated the relationship of art and artist to modernity. Groupings of paintings challenged, for example, historical perceptions of family, friendship, artist models, studio space, flower painting, religion, and politics. Scholars have widely discussed some connections, like lack of access to education. Others, such as controversies around certain objects, even feminist scholarship has largely neglected. Few viewers would recognize, for instance, that gloves indicated a certain stance about sexual equality.

Women’s Symbols of Modernity

As curator Lene Bøgh Rønberg explained to me, understanding the symbolism of gloves is key to interpreting several of the portraits. Gloves served as a key signifier in a Norwegian and Danish morality debates. This fashion accessory might indicate the wearer’s agreement with equal standards for extramarital sex and for rights to erotic pleasure. In the Hirschsprung show, the canvas arrangements and the wall text situated below the grouping elucidate the basic premise of “glove morality” (figure 4).

Bøgh Rønberg provides added depth and nuance to the exhibit in her excellent catalog essay. For instance, Bøgh Rønberg explains the evidence that the leather gloves, prominent in Susette Holten’s portrait of Alice Tutein (1869–1958, figure 5), likely signified the sitter’s stance in the morality debate. Tutein had a child before marrying the child’s father, author Gustav Wied (1858–1914), who was openly critical of bourgeois sexual double-standards (Lene Bøgh Rønberg, “The Glove in the Hand: Gloves and ‘Glove Morality’ in Portraits of the New Women,” in Women Artists in Denmark, 1880–1910, 216). The entire catalog is well-illustrated and effectively organized, helpfully available in both Danish and English.

The Hirschsprung must be commended for this superb exhibition and for their continued efforts towards the purchase and exhibition of works by Denmark’s women artists that round out their collection focus.

Against All Odds at the Statens Museum for Kunst

Across the park, the Statens Museum for Kunst (SMK) hosted a related exhibit, which Emilie Boe Bierlich curated. In contrast to the Danish focus of the Hirschsprung collection and its exhibition, Boe Bierlich emphasized the international networks that linked women artists of this period. Similar in scope and size, focusing on 23–24 artists, Boe Bierlich’s exhibit had a different ambience and curatorial premise. Against All Odds: Historical Women and New Algorithms focused on an international network and included media other than painting. The show also innovated by trying to use digital technologies to refashion or reimagine the artists in the present. This exhibit was tremendously successful and intellectually engaging. However, I came away feeling somewhat less satiated than I had at the Hirschsprung, even though the latter was more traditional. Against All Odds centered on more abstract concepts and offered less storytelling, and the technology did not necessarily deepen the visitors’ knowledge about the international network of artists.

The curatorial design team constructed the main exhibition area of Against All Odds to radiate into points away from the center gathering area rather than guiding viewers along a fixed linear path. The exhibit’s spatial arrangement seemingly replicated a rhizome, a philosophical model of connections based on the writings of the French philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari. The pairing of digital technology and new ways of approaching art history is a current priority of the SMK. Art historian Merete Sanderhoff, curator for digital technology, cites Deleuze and Guattari’s rhizome metaphors in her online anthology.

Twenty-first-Century Technologies

Against All Odds made engaging use of digital technologies. It expanded both the typical audience for women’s art and challenged the conventional ways to exhibit and to study this generation of women artists. One of the most remarkable and memorable contributions of the exhibit was its use of artificial intelligence (AI) to reinterpret the pixels of works of art from a previous century and to identify data patterns. For instance, one of the strongest graphic elements was the network map that charted cities where the artists converged. While the display was effective, it offered no surprising insights. Paris was the place where most of the careers converged, followed by Scandinavian capitals like Copenhagen and Stockholm (figure 6).

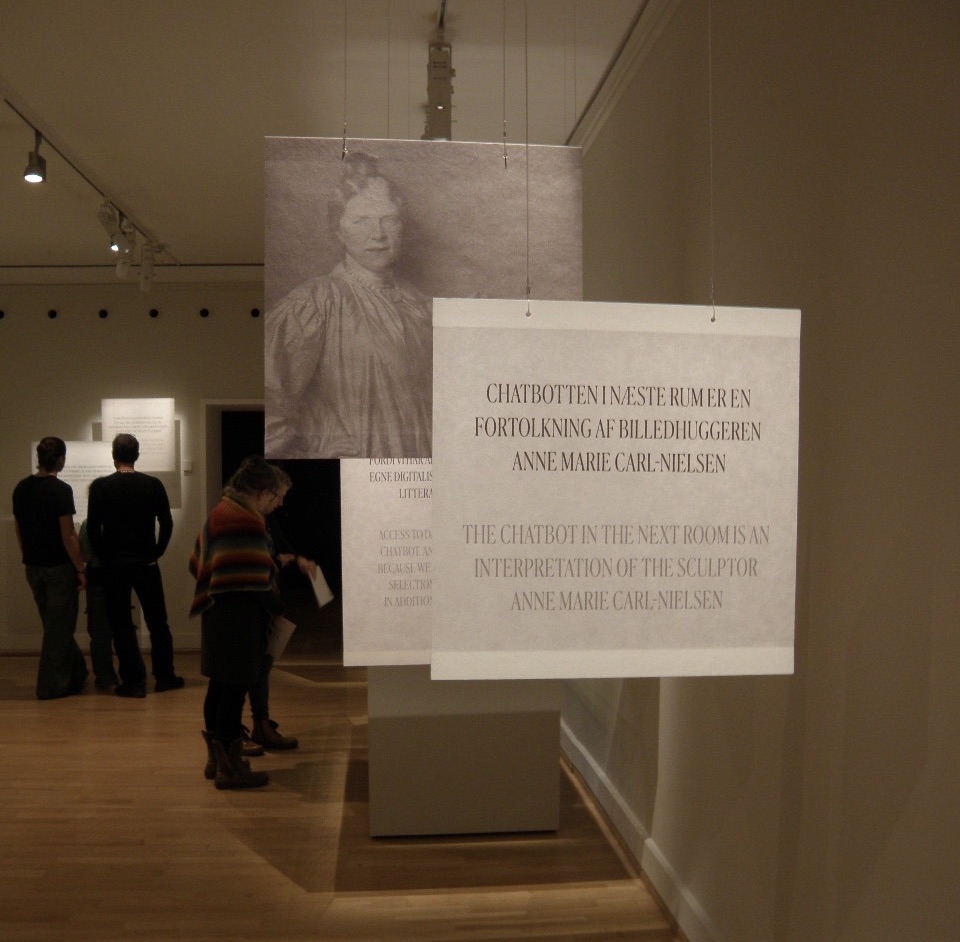

In a special room, visitors could question a chatbot impersonating the sculptor Anne Marie Carl Nielsen (1863-1945). The installation included suggested queries, and the responses were predicted based on letters, diaries, and recent scholarly publications. Three students at The Technical University of Denmark’s Department of Applied Mathematics and Computer Science (DTU Compute) developed the chatbot based on a previous prototype designed to facilitate communication with hearing-impaired individuals. This use of new technologies helped suggest possibilities of how to reengage with an artist eclipsed in the historical record (figure 7).

Interesting in their own right as digital art, the installations by Ix Shells (born 1990, Panama) were somewhat disruptive. Ix Shells intended the installations to transform data from the historical art and lives of the exhibited women into two states, one encouraging the visitor to “surrender to the meditative state of the work,” the other to “physically connect with the female artists’ movements in the world across time.” Intellectually, visually, and experientially Shells’s installations are intriguing. For many of us, however, they did not amplify the artists whose works were displayed (figure 8).

Artmaking of Consequence

One of the most successful non-digital interventions was a section pairing the sculptor with the lesser-known Marie Henriques (1866–1944). This is unsurprising, as Boe Bierlich wrote her dissertation about and curated a lauded exhibition on Carl Nielsen, Pairing Henriques’s evocative mixed media works on paper, like Eythidikos Kore (figure 9).

And Carl Nielsen ’s large-scale archaic sculptures made in Athens and funded by the Anckerske Grant in 1903 helped, as the exhibition didactic explains, “to undermine a moral and aesthetic dogma in European culture … that believed that antique sculptures were white” (figure 10). One banner here raised the issue of “art or copy.” Another banner addressed the importance to their contemporary scholars and artist peers of having exhibition-quality copies of Archaic classical sculptures.

There were magnificent works on exhibit by accomplished artists. Evocative symbolist paintings by Finn Ellen Thesleff (1869–1954), landscapes by Norwegian Kitty Kielland (1843–1914), interiors by Eva Bonnier (1857–1909), appeared alongside Danish artists like Carl Nielsen, Bertha Wegmann (1847–1926) and Anna Ancher (1859–1935), who have been the subject of recent solo shows in Copenhagen.

Käthe Kollwitz: Mensch

In a poignant complement to the two group shows on Scandinavian artists, SMK offered a breathtaking solo exhibition that explored the career of Käthe Kollwitz (1867–1945) (figures 11, 12). The exhibition paired careful analyses of Kollwitz’s technique as a graphic artist and a sculptor with her overriding concern for humanity, her “mensch” qualities.

The curatorial team included insightful technical observations. These invited a careful and fresh re-examination of familiar prints, like Charge from the series The Peasants War, 1902–1903 (figure 13). It was thus clear how the artist innovated, adjusting line weights, using the texture of the paper, wiping and scratching the plate.

An Artistic Focus on the Human Condition

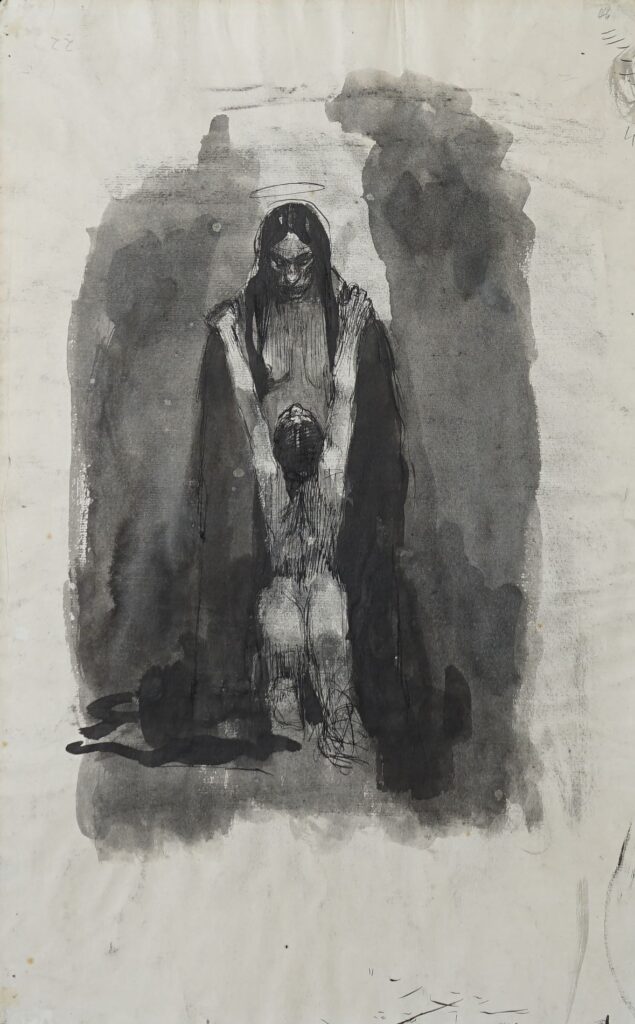

The exhibition included sheets of figure studies depicting women, examples of an illustration from Goethe’s Faust (1899), and expressive unpublished pen-and-ink drawings like Woman Kneeling Before a Female Deity (ca. 1889) (figure 14). The curatorial text summarized about works depicting mothers with children, Kollwitz “anchors them in a bodily and female universe of experience, transforming them into modern icons of the human condition.” This claim that Kollwitz visualizes the “human condition” applies to many other works on exhibit, beyond the many images of mothers and children.

The exhibition also made a strong presentation of Kollwitz’s public art. Her posters unequivocally demanded an end to warfare. Drawings reflect on the horrendous losses of both world wars as women cradle corpses, beg for food for their hungry children, and fold over in grief. Kollwitz and her generation survived such hardships during the wars.

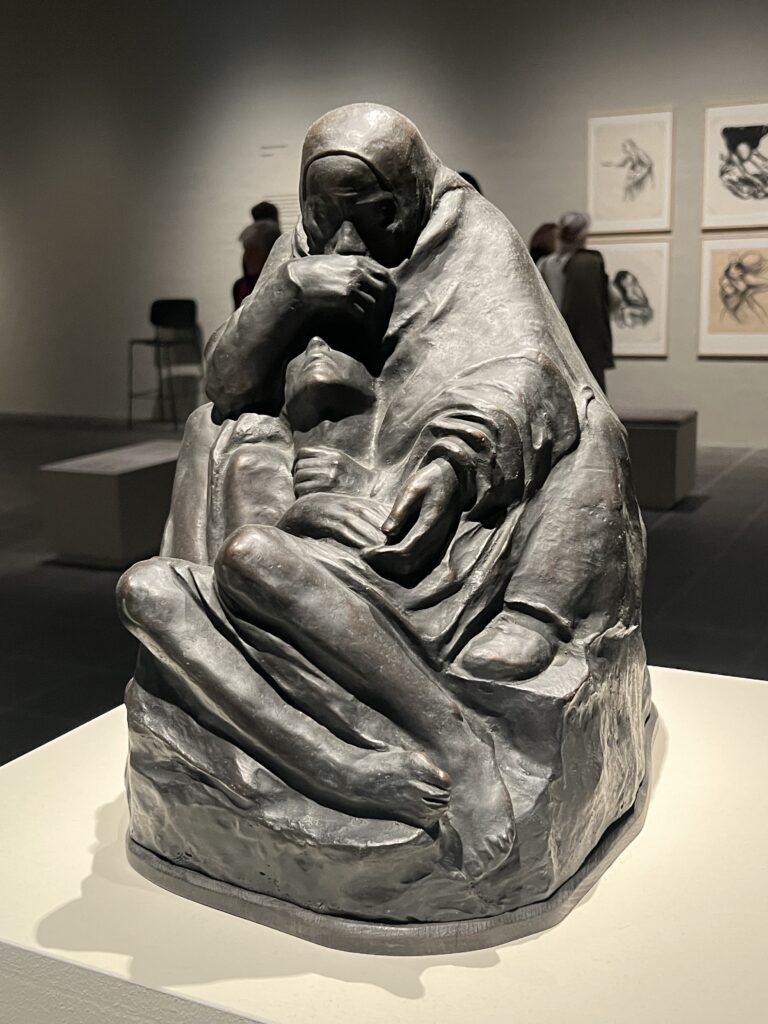

Sculptures and graphic works both monumentalized and reified maternal pain, like her own as a survivor who lost a son in the First World War and a grandson in the Second (figure 15). A 1937 sculpture offers an alternative to the losses. A group of full-bodied, mature women lock arms as a “Tower of Mothers,” protecting the hidden interior from the ravages they had witnessed (figure 16).

A Missed Opportunity

Kollwitz was a contemporary of the artists exhibited across the lobby in Against All Odds, who may well have had points of contact in Secession exhibitions in Berlin or through artist publications like Simplicissimus. However, her art was radically different, like her life in the German Empire, a neighboring country with many ties to Scandinavia’s artists and authors. I would have loved to see a more overt dialog between these two exhibits, one that explored individual experience as a woman artist; the other the corporate experience of women art makers from Nordic countries. The proximate exhibitions missed an opportunity to consider the fragility and gaps in artistic networks. They left me wondering why Kollwitz felt emboldened to use her art as a vehicle of protest and call for action, and why her career did not fall into obscurity, whereas relatively few across the last century recognize much of the skillful and evocative art exhibited in Against All Odds.

Exhibition information

Den Hirschsprunske Samling presented Women Visualizing the Modern: Danish Art 1880–1910 / Kvindernes moderne gennembrud. Dansk kunst 1880–1910 from August 28, 2024 to January 12, 2025). The show is on at Randers Kunstmuseum from February 8 to May 11, 2025). An exhibition catalog is available.

Statens Museum for Kunst presented Against All Odds—Historical Women and New Algorithms / Against All Odds—Historiske Kvinder og nye algoritmer from August 31–December 8, 2024.

Statens Museum for Kunst presented Käthe Kollwitz—Mensch (Human) from November 7, 2024 to February 23, 2025.

Alice M. Rudy Price received a Ph.D. in art history from Temple University, Tyler School of Art and Architecture. Price and Emily C. Burns are the editors of Mapping Impressionist Painting in a Transnational Context (Routledge, 2021). Burns and Price are under contract for their next 2-volume collaboration, Routledge Companion to Art and Formation of Empire, due out in May 2025 and Routledge Companion to Art and Challenges to Empire due out late 2025. Price’s dissertation on the Danish artist, Anna Ancher (1859–1935), addressed the artist in relation to the intersecting cultural contexts of rural Denmark, the Skagen Art Colony, Copenhagen and Paris. Her larger project considers the visibility and invisibility of the aging woman’s body in modernist discourse. Her curatorial partnership on the exhibit “Aging Bodies, Mature Careers,” with Ribe Art Museum, the Skovgaard Museum, and Bornholm Art Museum, is supported by the New Carlsberg Foundation. The exhibit will run in Denmark from May 2026 through 2027.

Alice Price is an adjunct assistant professor at Tyler and other Philadelphia universities. She also holds master’s degrees in education and history. Follow her on LinkedIn.

More Art Herstory guest posts by Alice M. Rudy Price:

Anna Ancher’s Vaccination and Scientific Motherhood, by Alice M. Rudy Price

Marie Laurencin: Sapphic Paris, A Review, by Alice M. Rudy Price

Other Art Herstory blog posts you might enjoy:

Anna Boberg: Artist, Wife, Polar Explorer, by Isabelle Gapp

Nancy Sharp: An Undeservedly Forgotten Exemplar of Modern British Painting, by Christopher Fauske

Frida: Beyond the Myth at the Dallas Museum of Art, by Olivia Turner

The Cheerful Abstractions of Alma Thomas, by Alexandra Kiely

A Quiet Eye—The Unique Achievement of Sylvia Shaw Judson, by Rowena Loverance

Defining Moments: Mary Cassatt and Helen McNicoll in 1913, by Julie Nash

Women Artists from Savannah at the Telfair Academy Museum, by Julie Allen

Dalla Husband’s Contribution to Atelier 17, by Silvano Levy

Esther Pressoir: Imagining the Modern Woman, by Suzanne Scanlan

The Life and Art of Dorothea Tanning, by Victoria Carruthers