Guest post by Christopher Fauske, Salem State University

Introduction

The life and work of British artist Nancy Sharp (1909–2001) coincides almost perfectly with the past century.

Talented—her paintings would several times be highlighted in reviews of shows—Sharp also despised self-promotion. A failed marriage, a war, a second marriage ended by a death just days before the end of the war in Europe, left her a single mother of three uncertain about the future. But she got on with making a life. She painted. She taught students from backgrounds quite distinct from hers. She had affairs. She raised a family (albeit not always in a manner her children found particularly sympathetic or admirable). Sharp could be, well, sharp. She could be dismissive of others, or just plain rude. But she could be suddenly attentive, engagingly curious, and charmingly gossipy. She lived not just through the century, but of it and in it, and always as herself, reckless, unapologetic, careless of reputation.

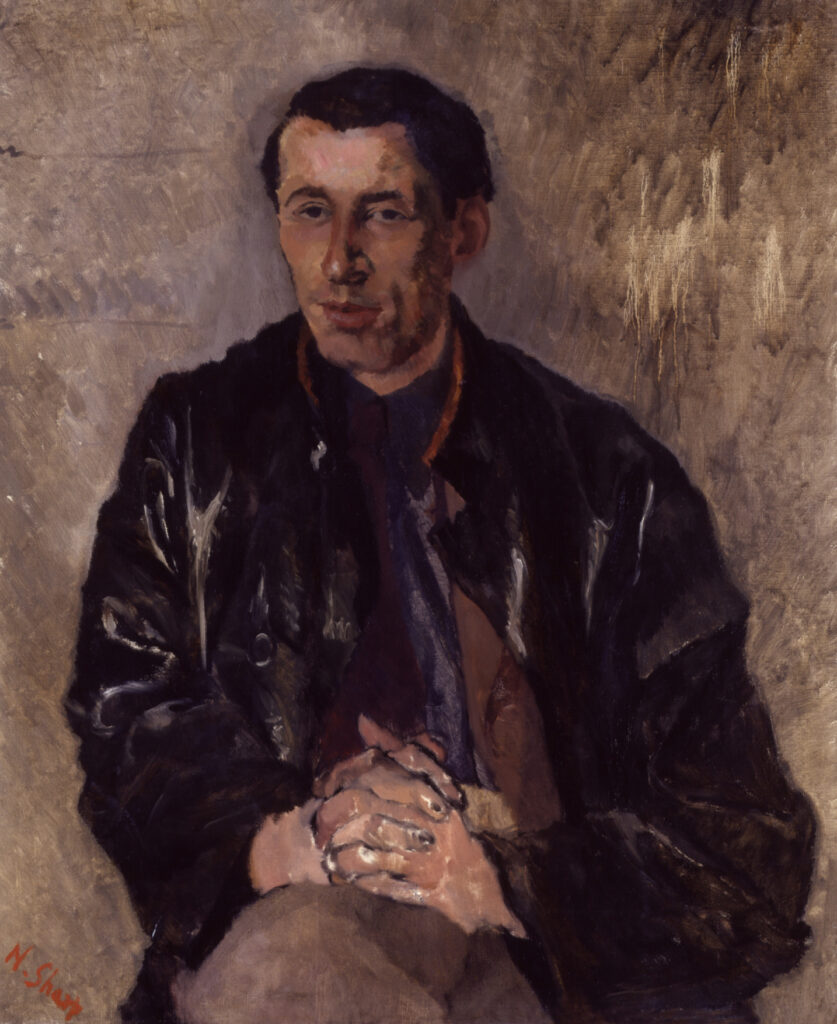

A figurative painter of fine eye and inevitable vitality, Sharp also produced stunning portraits of well-known contemporaries, including Louis MacNeice, Trevor Huddleston, and Sir John Summerson, among others. Like so many women of her generation—and many generations before—Sharp exists now passing through histories and biographies, someone known or encountered by others, rather than as an agent of her own life. But she is important not just for her art, but for her contributions to British life and culture in general. It is past time for her story to be told.

Education

Nancy Sharp was born on October 29, 1909 in Truro, Cornwall, the younger daughter of Dr. Hugh Culliford Sharp. Hers was a family representative of the transition that would affect many comfortably well-off professional families. The consequences of World War I and post-war social realignment meant daughters of professional families were increasingly likely to be educated beyond the expectations of a society lady. Sharp attended Cheltenham Ladies’ College (1923–27), where Margaret Ithell Colquhoun was among her classmates. When she graduated, she was trying to decide between further studying to become a vet or an artist.

She enrolled first at the Chelsea School of Art, studying with Percy Hague Jowett. Having won a prize for illustration and design early in July 1928, Sharp secured an interview with Henry Tonks, principal at the Slade School of Fine Art and enrolled there as a full-time student in September 1928, graduating in 1931.

“A lively, talented girl”

At the Slade, Rodrigo Moynihan identified her as one of “a group of lively, talented high-spirited girls,” along with Elinor Bellingham-Smith and Nicolette Macnamara. Sharp and Macnamara shared a studio that

was a barrack-like place with a glass-domed roof. And there we slept and ate and had parties …We lived in squalor. The beds were like old dog baskets. Our dirty washing and laundry piled up in a corner for weeks on end … The washing-up fouled the sink until we washed up in desperation … Our clothes hung on hooks from the wall when they were not on the floor among the canvases and paints and empty beer bottles left over from parties. The mice approved of our way of living and multiplied. We were terribly happy.

[Two Flamboyant Fathers, 158–9.]

Sharp was recognized by her peers as a painter with enormous talent and potential. Julian Bell once tried to get Victor Pasmore to talk about some of their contemporaries, but Pasmore had little to say except “how much he admired Nancy’s painting.” In 1929, she exhibited as part of The London Group for the first time, and in 1930 was one of the artists selected for the First Exhibition of the Young Painters Society, receiving, she recorded in her notebook, “Good reviews.”

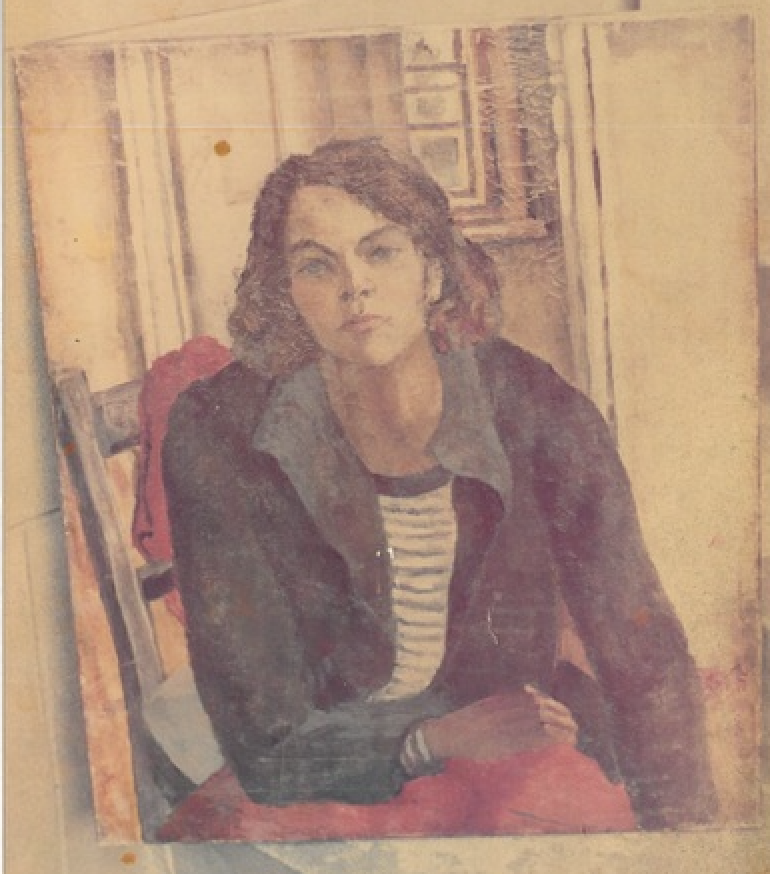

First marriage and two daughters

Sharp and William Coldstream, a fellow Slade student, wed in a civil ceremony at St. Pancras Town Hall in London on July 22, 1931. From September, they shared a studio and flat at 10 Regent Square that friends nicknamed the “jam factory” for the apparent explosion that had taken place inside it.Their first daughter, Juliet, was born on September 2, 1932. A second daughter, Miranda, was born on July 18, 1935, by which time Sharp and Coldstream were established in Belsize Park, along with a lodger, W. H. Auden. Largely overwhelmed with domestic chores while Coldstream worked at the GPO Film Unit and then at the Euston Road School, which he helped establish, Sharp continued to paint in her free time. But her exhibiting was restricted to annual London Group shows.

Sharp and Coldstream increasingly drifted apart, though with various attempts at reconciliation. In the late 1930s Sharp had an affair with Louis MacNeice, whom she met through Auden. This relationship reinvigorated her, and she illustrated two of his books, I Crossed the Minch and Zoo. He would also inspire her to paint his portrait. Several cantos of Autumn Journal record MacNeice’s view of their relationship.

World War II, second marriage and a son

When World War II started, Sharp joined the London Auxiliary Ambulance Service as an ambulance attendant and driver. Her ambulance was the only one to reach Silvertown, east London, on the first night of the Blitz, and she was reportedly recommended for the George Medal, a newly created award to recognize “acts of great bravery … not in the face of the enemy.” However, “her boss … forgot to send in his recommendation.” Her letters and journals recount several instances of significant bravery and resilience in the midst of almost unimaginable bloodshed, loss of life, and gore.

Throughout the war, Sharp exhibited at various shows, including the inaugural Civil Defence Artists’ exhibition, “An exhibition of paintings, drawings, sculpture by artists of fame and of promise” and as part of the “United Artists’ exhibition.” She recorded in a letter that Her Portrait of Mme Etoile “got a good notice,” in the November 4, 1943 Listener: “the quiet wit of Nancy Sharp, who, inspired by Seurat, has produced in L’Etoile the most original picture in the [London Group] show.”

Before the war Sharp had met Michael Spender, brother of the poet Stephen Spender. In 1942, she divorced Coldstream and in 1943 married Spender. Their son, Philip, was born on December 26, 1943. Michael Spender was killed in an air crash during the last week of the war in Europe.

A career in teaching

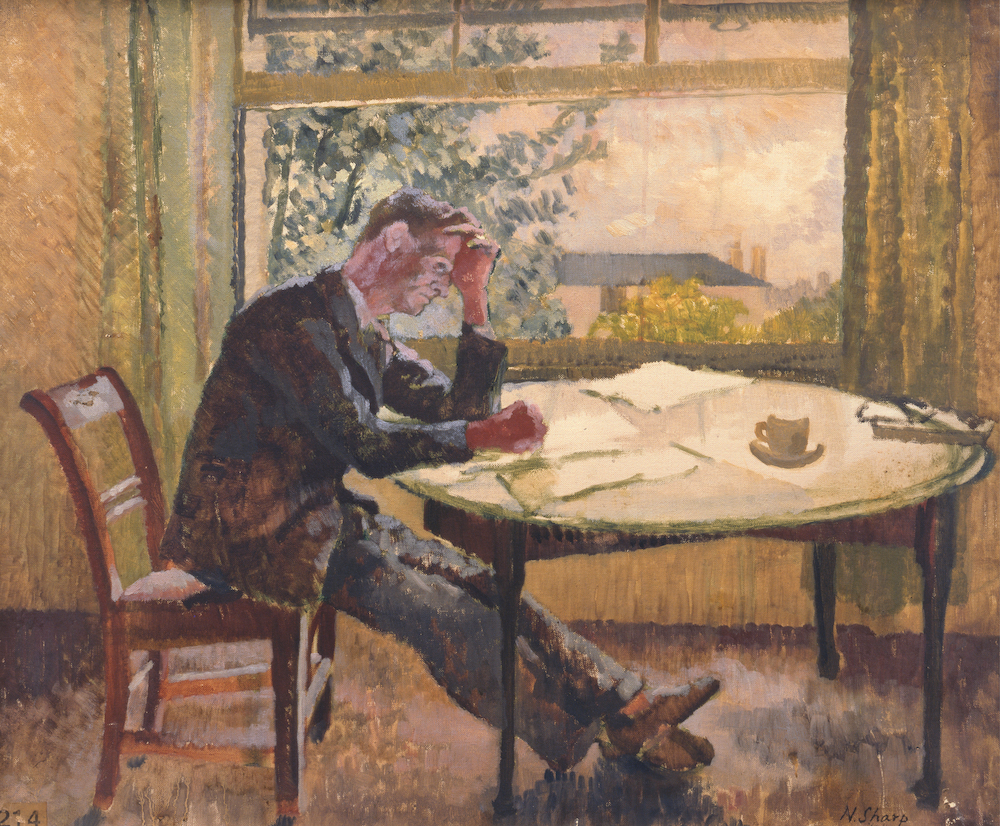

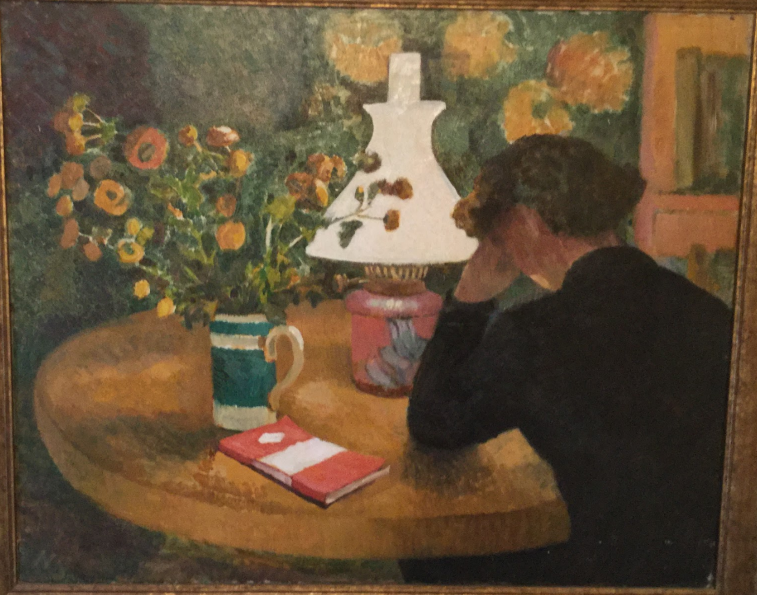

Sharp made her living for the next thirty years as an art teacher. She taught first at a local preparatory school; then at Kinnaird Park School in Bromley, southeast London; and then at Archbishop Temple’s School in Lambeth. At Kinnaird Park School she had an affair with the principal, Jean Forth, and painted a delightful intimate portrait of her reading at her desk.

invited back to Archbishop Tenison’s successor school, Archbishop Ramsey’s, to present the 1983 art awards, Sharp told the students

I spent 15 years [here] altogether and I can truthfully say there was never a dull moment. The special thing about Art is that it is so exciting—one never can tell who is suddenly going to produce something quite marvellous, or hilariously funny, apart from those who really work hard and get on.

Nancy Sharp, remarks at Archbishop Ramsay’s School prize day, 1983; quoted from her journal (private collection)

Sharp taught four days a week, reserving Fridays and weekends for painting, along with summer for travel to locations where she wished to undertake more detailed studies. But although she exhibited at one or two shows a year, her lack of interest in self-promotion, along with the significant constraints on her time that came from having to work for a living, meant that much of her work remained unseen and unappreciated until late in her life.

Retirement and rediscovery

Sharp lived in the Chalk Farm area of Camden, northwest London, where she was active in her local Church of England parish. Through that involvement she had the opportunity to paint the portrait of Bishop (later Archbishop) Trevor Huddleston. In Chalk Farm, she lived in close proximity to several significant figures in British arts, including Sir John Summerson, with whom she would have an affair for many years, and whose portrait she would paint.

Sharp continued to exhibit throughout her life. After her retirement she took the opportunity to expand both the quantity and range of her work. She became an integral part of the community of adult artists taking workshops with Peter Freeth at the Camden Institute in Kentish Town.

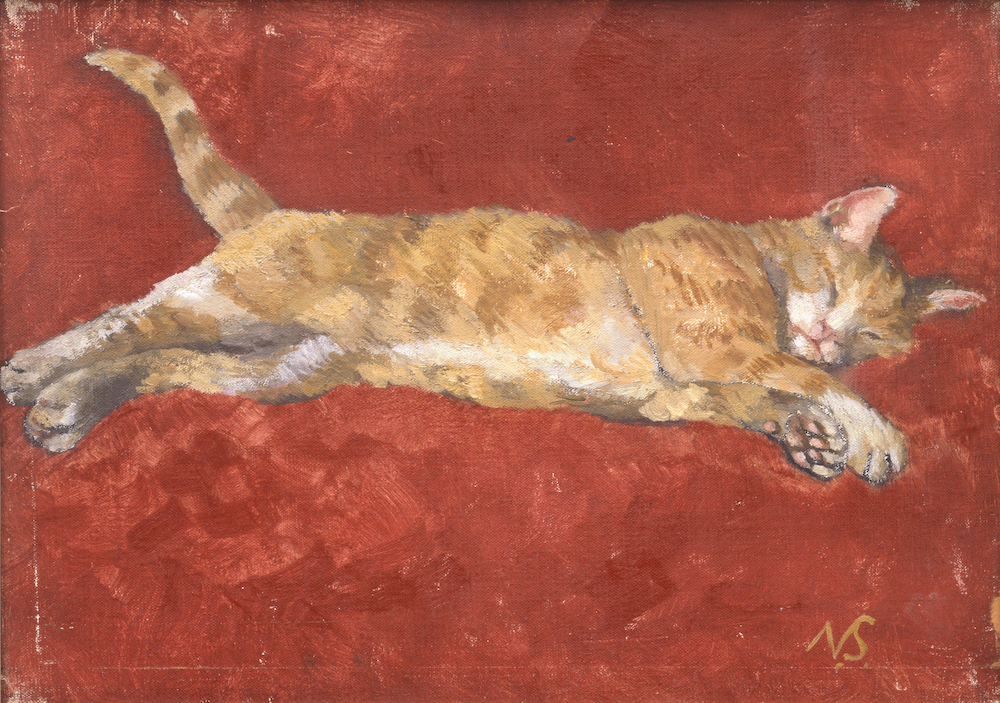

Toward the end of her life, encouraged by members of her Camden Institute classes, she began to have a few solo shows or to participate in small group exhibitions. At the time of her death in 2001, her reputation was starting to rise, albeit that her work was representative of a particular world view. She was a realist first and foremost, with a fine eye for the small details that give her paintings an immediate sense of vibrancy.

Nancy Sharp’s impact: observations by those who knew her

It’s shameful that Nancy Sharp has been forgotten in the history of C20th painting, and it’s not just the name change being a problem. It was domesticity, the men prioritising their own work, love affairs. When you read about Nancy Sharp’s life … it’s a wonder she did any painting at all.

—[Nicola Beauman], “The Persephone Post,” 6 January 2022

In the end I exhibited quite a body of work by her, which, had I seen it all at the beginning, would probably have been enough for a solo exhibition. I would love to have done it. The fact that I exhibited her work in a rather piece-meal way was in a way her choice rather than mine. Assessment of her work in terms of quality and quantity was not easy as she always showed me a few pieces at a time, away from her studio. I never had a good idea of how much there was. [I would] rate her best work very highly — excellent examples of Modern British painting.

—Sally Hunter, email correspondence

I was only a year out of drama school and eager to enter what I thought of as the slightly piratical artistic world when Nancy invited some of us to drinks at her home near Hampstead Heath … I remember the house clearly, tall windows, large rooms crammed with unexplained canvases … It was a brief and unique period, and I now realise that Nancy was a genuine, underrated talent, and an important relic of an era I wish I’d known and appreciated more of … A bunch of “politically committed” teachers, we thought of her as “one of us” — if only we’d known how much she could have taught us if only we’d taken the time to listen!

—Barry Simner, email correspondence

[She was someone] who was for me what is called an education—or rather illumination; so feminine that I sometimes felt like leaving the country at once; and so easily hurt that to be with her could be agony. She could be so gloomy as to black-out London and again she could be so gay that I would ask myself where I had been before I knew her and was I not colour-blind then. Of all the people I have known she could be the most radiant. Which is why I do not regret the hours and hours of argument and melancholy, the unanswerable lamentations of someone who wanted to be happy in a way that was just not practical.

—Louis MacNeice, The Strings Are False: An Unfinished Autobiography, ed E.R. Dodds (London: Faber, 1965), pp. 170–71.

[Nancy] dashed in vigorously with a broad brush, the heroine perhaps of some thirties novel I hadn’t read … She was pugnacious, mischievous, and occasionally snobbish. She didn’t suffer fools gladly and enjoyed the occasional scrap—the occasional cigarette, the occasional tipple. She had a marvellous, wicked, cackle and was not above a little schadenfreude … When her health began to prevent her reaching the Etching Department … we realized, missing her, that we had loved her in all her modes, acerbic, sharp, and ironic, witty, occasionally affectionate, delightfully, roguishly tipsy at our various celebrations.

—Peter Freeth, “Nancy Spender at the Camden Institute,” in Nancy Sharp (Nancy Spender), 1909–2001 Memorial Exhibition: Paintings & Works on Paper (London: The Estate of Nancy Spender, 2002), np.]

[Where not otherwise cited, information is drawn from the manuscript of Christopher Fauske’s full-length study of Nancy Sharp currently in preparation.]

Christopher Fauske is emeritus professor of media and communication at Salem State University and the author of books ranging from topics such as the eighteenth-century Church of Ireland to translations from the Norwegian of works by both Alexander and Kitty Kielland. He writes regularly about Essex for County Cricket Matters and is just completing the first full-length study of Nancy Sharp.

More Art Herstory blog posts you might enjoy:

British Women Artist-Activists at The Clark Art Institute, by Erika Gaffney

Modern Women Artists in Copenhagen 2024–2025: Three Exhibitions, by Alice M. Rudy Price

Frida: Beyond the Myth at the Dallas Museum of Art, by Olivia Turner

A Quiet Eye—The Unique Achievement of Sylvia Shaw Judson, by Rowena Loverance

Esther Pressoir: Imagining the Modern Woman, by Suzanne Scanlan

Reflections on the Audacious Art Activist and Trailblazer Augusta Savage, by Sandy Rattler

Women Artists from Savannah at the Telfair Academy Museum, by Julie Allen

The Cheerful Abstractions of Alma Thomas, by Alexandra Kiely

Defining Moments: Mary Cassatt and Helen McNicoll in 1913, by Julie Nash

The Life and Art of Dorothea Tanning, by Victoria Carruthers

Anna Boberg: Artist, Wife, Polar Explorer, by Isabelle Gapp

Anna Ancher’s Vaccination and Scientific Motherhood, by Alice M. Rudy Price

Dalla Husband’s Contribution to Atelier 17, by Silvano Levy

Deirdre Burnett: A Significant British Ceramic Artist Remembered, by Jo Lloyd