How to characterize an art exhibition as sweeping and ambitious as Making Her Mark: A History of Women Artists in Europe, 1400–1800? The first term that leaps to mind is “challenging”—and it applies in more than one sense of the word. Spoiler alert: we conclude that the curators met the organizational challenges imaginatively, and to astounding effect. (This perception is not peculiar to us. Feedback from friends and professional contacts includes phrases such as “fabulous,” “I was blown away,” “what an outstanding exhibition,” and even “the best show I’ve ever seen in my life”!) And there is an element of challenge in the exhibition’s intent and impact, as well.

Organizational and conceptual challenges

So, we perceive layers of challenge in Making Her Mark:

- By focusing entirely on female artists, it challenges the art historical canon.

- In displaying sketchbooks, textiles, ceramics and other items of material culture side-by-side with paintings and sculptures, it challenges traditional hierarchies within art history, as well as the distinction between “art” and “craft.”

- We can readily imagine the organizational challenges the curatorial team—Andaleeb Badiee Banta, Alexa Greist, and Theresa Kutasz Christensen—faced in deciding on how to deploy the 235 objects in the show throughout the 12 galleries at the Baltimore Museum of Art (BMA). There may also be challenges adapting the exhibition to the physical set-up at the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO), to which the show travels in late March 2024.

- How complex was the selection process that resulted in those specific artworks and artefacts? We understand that the curatorial team sent out some 400 loan letters. They worked with 70 lenders in 6 countries—Canada, Italy, UK, Sweden, Portugal, and all over the US. The lending institutions range from art and history museums, academic museums, and regional collections to libraries, private collections, and convents.

- The October 2023 opening of Women Masters at Madrid’s Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza and Ingenious Women: Women Artists and their Companions at Bucerius Kunst Forum in Hamburg may also have presented complexities. Given that both shows focus at least partially on art by premodern women, it stands to reason that the curators for all three exhibitions would have needed to steer around one another’s loan selections.

- As the exhibition catalog specifies, certain media are too fragile and difficult to transport. Thus wax sculptures by Anna Morandi Manzolini and Caterina Julianis, and paper collages by Mary Delany, to note just a few examples, could not be included.

- And finally, Making Her Mark is a challenging show to write about. The impressive variety of artists and mediums on display makes it impossible for a single review to represent every item and maker. (But see below for links to other reviews!)

Rising to the challenges

Thematic organization

The objects on display in Making Her Mark are displayed thematically, rather than by artist, medium, or chronology. The four overarching themes are “Faith & Power,” “Interiority,” “The Scientific Impulse,” and “The Entrepreneurial Spirit.”

Inevitably, especially in such an extensive exhibit, there’s bound to be some overlap. For example, Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith and Her Maidservant with the Head of Holofernes appears—dramatically and to excellent effect—in the “Faith and Power” section of the show. But as Mary Garrard points out in her Art Herstory guest post Two of a Kind: Giovanna Garzoni and Artemisia Gentileschi, “The dramatic curved shadow that overlays the Detroit Judith’s head echoes Galileo’s drawings of the moon’s phases.” On this basis, it wouldn’t have been wrong to position the painting in “The Scientific Impulse.”

The potential for overlap seemed to us most pronounced within the subsections of “The Scientific Impulse.” The curatorial team used a fluid, open-ended layout to meet this particular challenge. It seems to be up to the viewer’s discretion to determine, for example, where the “Women of the Garden” ends and “The Art of Science” begins.

More advantages of the thematic approach

One benefit of the thematic structure is that works by the same artist may appear in different rooms. As we observed in our review of the Wadsworth iteration of By Her Hand, which also followed a thematic organization, this means that viewers have pleasure of re-encountering an artist again later as they wend their way through the galleries.

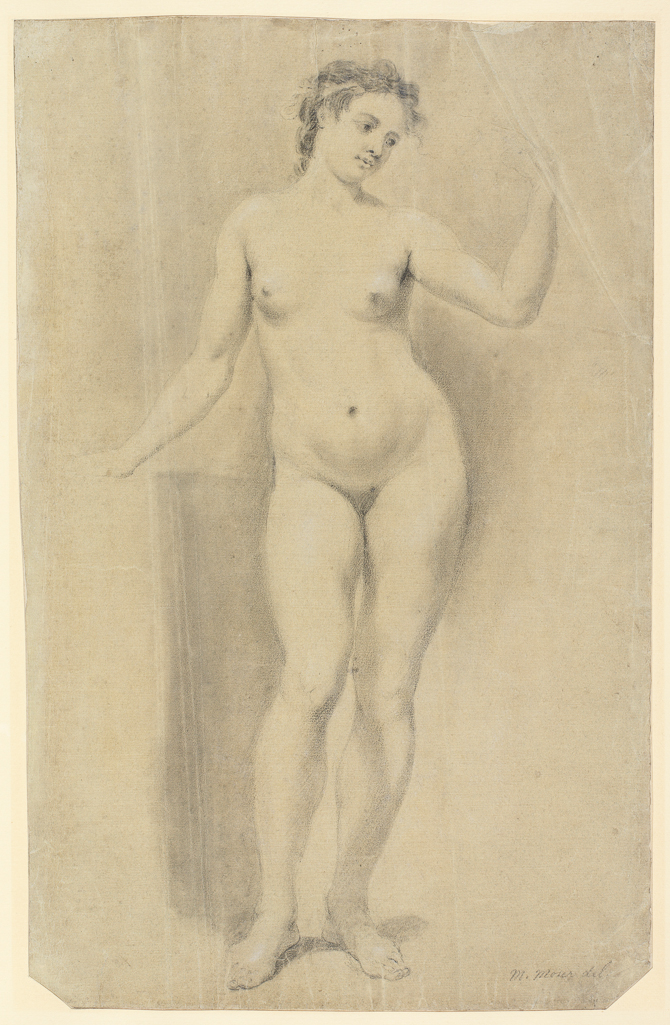

In presenting the works by theme, the organizers subtly convey the message that we needn’t pigeonhole the artists. Take Mary Moser as just one example. This British artist, one of only two female founding members of the Royal Academy, is best known as a flower painter. And certainly, she is represented in the garden sub-section of Making Her Mark. But the viewer runs into her again in “Drawing and the Body,” where Moser’s Standing Female Nude appears.

In Making Her Mark, the thematic grouping allows for the placement of seemingly disparate objects in such a way as to highlight connections among them. For example, a painting by Lavinia Fontana, who had a special gift for portraying textiles in two dimensions, is displayed alongside a specimen of lace from the artist’s time and culture.

And finally, the thematic display strategy prevents any one artist from dominating the exhibition.

Digital interventions

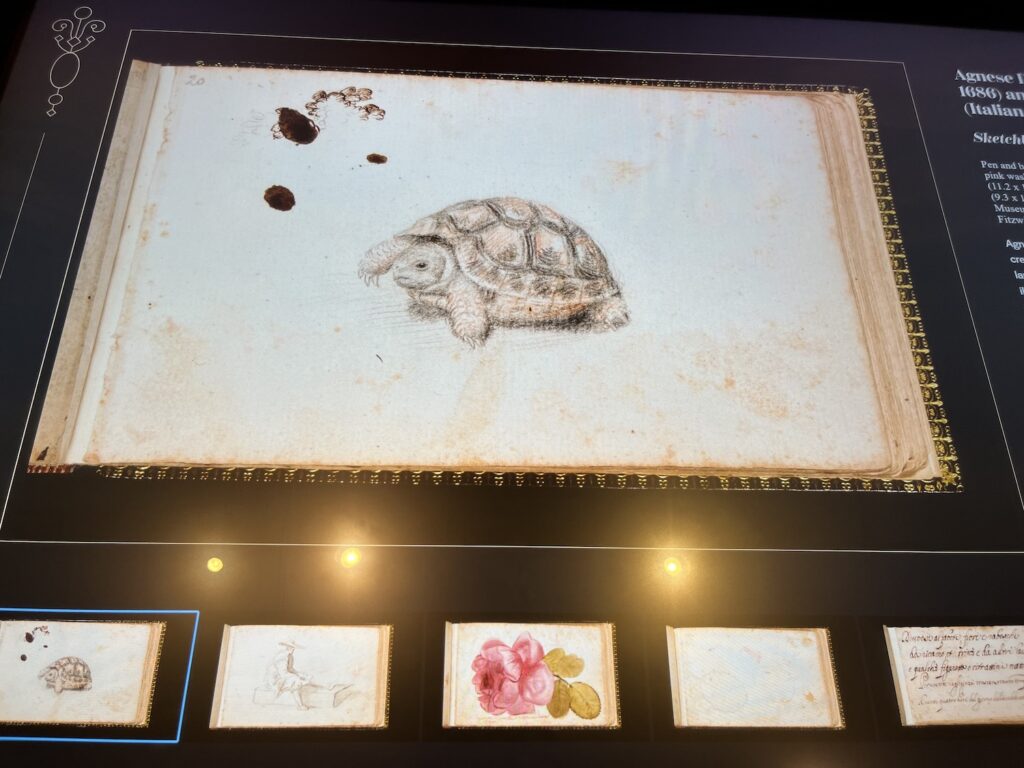

The exhibition includes a number of sketchbooks, albums and printed books, which are presented in clear display cases. Each is open to a particular page. Therefore, among many other decisions, the curatorial team had to decide with books on which page-spread to expose. It follows unavoidably that many pages in each book are not visible to viewers. But the curators use digital technology to make at least some of the multi-page works more accessible. Midway through the show, large interactive panels allow visitors to “leaf through” a couple of works electronically.

Emphasizing the continuity between creative women of the past and the present, the organizers collaborate with four contemporary female makers: painter Monica Ikegwu; fiber artist Sasha Baskin; embroiderer-scholar-engineer Tricia Nguyen Wilson; and sculptor Syd Carpenter. These artists, as well as BMA curator Andaleeb Banta, provide commentary on sixteen objects, which visitors can access (using their own devises) through another digital intervention: QR codes sprinkled throughout the exhibition.

Tactile interventions

As mentioned above, this show features objects of material culture that haven’t traditionally been privileged in art history. In addition to oil paintings, drawings, prints, and sculptures (in marble, but also wax, paper, and other perhaps unexpected materials), and miniatures, the galleries showcase embroidery, paper-work, lace, tapestries, glassware, clothing, ceramics, silverwork, furniture, devotional objects, printed books, and manuscript illuminations.

Rightly discerning that viewers would love to touch these items, the curatorial team offers some outlet for that tactile instinct. In the same gallery that contains the digital panel, there’s a bench containing materials which visitors are encouraged to handle. These items include a lacework-in-progress (with bobbins attached); vellum; and jasperware, among other representative textures.

The Artists

Known entities

The exhibition brings together a vast array of makers. In some cases, the artists’ names are known; but in other cases, the names have been lost to time. Among the attributable works are some very familiar names, including (but not limited to) Sofonisba Anguissola, Rosalba Carriera, Lavinia Fontana, Giovanna Garzoni, Artemisia Gentileschi, Catharina van Hemessen, Angelica Kauffman, Adelaide Labille-Guiard, Judith Leyster, Diana Mantuana, Maria Sibylla Merian, Clara Peeters, Rachel Ruysch, Elisabetta Sirani, and Anne Vallayer-Coster.

New perspectives

Many of the artists’ names are not so well known, at least not to this viewer. Into this group fall Catherine Brandinn, Agnese Dolci, Dame Ann Hamilton, Margaretha Helm, M. K. Herbert, Andrea de Mena y Bitoria, Laura Piranesi, Susanne Maria von Sandrart, Elizabeth Pieth Schmitz, Geneviève Taillandier, among others.

Then there’s the group of artists your correspondent thought she knew… But here we discover another aspect of the maker’s oeuvre, or learn of previously unknown and unsuspected works. We have already alluded to Mary Moser’s figure drawing; prior to this exhibition, we knew only of her flower paintings. Other surprises include

- A paper-cutting by Anna Maria Garthwaite. Prior to viewing Making Her Mark, we had encountered Garthwaite only in the context of textile design.

- Three out of the four paintings by Josefa Ayala (also known as Josefa de Óbidos). None of these fall outside of her acknowledged specializations of still life and devotional painting. But we had never previously come across The Visitation; Still Life with Watermelon and Pears; or, most striking, Still Life with Fruit, Cardoon, and Carrots. (No, we had never before heard of “cardoon,” which, it turns out, is a close relative of the artichoke. It is edible, as presented in this painting; but it is also cultivated as an ornamental plant.)

Extraordinary objects

Given the number and variety of materials we list above that this exhibition embraces, it won’t surprise readers to learn there are some out-of-the-ordinary artefacts on display. We won’t attempt to list every item that falls into this category, but here are some representative examples:

- An eighteenth-century self-portrait in hairwork (yes, human hair!) by Mary Anne Harvey Bonnell, and a mixed-media (paper filigree, hairwork and watercolor) cabinet by the artist and her stepsister, Sophia Jane Marie Bonnell. As we entered the exhibition, a museum staffer (whose name we wish we had caught) led us, without giving away too much, to anticipate these two objects, specifically. He said, “They are going to mess with your mind.” He was not wrong.

- Two unattributed works created with rolled paper. The first is a quillwork picture with a Madonna and Child at the center. The second is a quilled Agnes Dei reliquary, brought by early Ursuline immigrants to what is now Quebec (it is still owned by the Ursulines of Quebec). At first glance it appears to be metalwork, but it is in fact made with the gilt edges of book pages.

- An embroidered portrait of a tiger by the eighteenth-century celebrity British needleworker Mary Linwood. Looking at this work on screen, you could easily believe it was an oil painting. Looking at it in person, the effect is not appreciably different!

Showcasing new BMA and AGO acquisitions

This show features works we’ve tracked from auction offering, to sale, to acquisition announcement. Some of these were acquired by the museums that host this show. The Baltimore Museum of Art now owns

- Self-Portrait, 1842, by Sarah Biffin, a nineteenth-century British artist born with phocomelia, or as her baptism record denotes, “born without arms and legs.” Using her mouth to paint, she achieved significant fame as a miniaturist in her lifetime.

- Blue Morning Glory and Narcissus, both c. 1760, by Barbara Regina Dietzsch, an eighteenth-century German painter whose name is not well known among today’s art lovers, though her works are held in more than a dozen public collections around the US, the UK, and Europe. These two gouache flower drawings are the subject of an Art Herstory guest post by Andaleeb Banta.

And the Art Gallery of Ontario has added to its collection

- Virgin Mary and Infant Jesus, c. 1575–80, by Barbara Longhi, a member of a family of painters in Renaissance Ravenna, Italy and one of only a few Renaissance women to succeed as a professional artist. The acquisition is discussed in detail in an AGO Insider article.

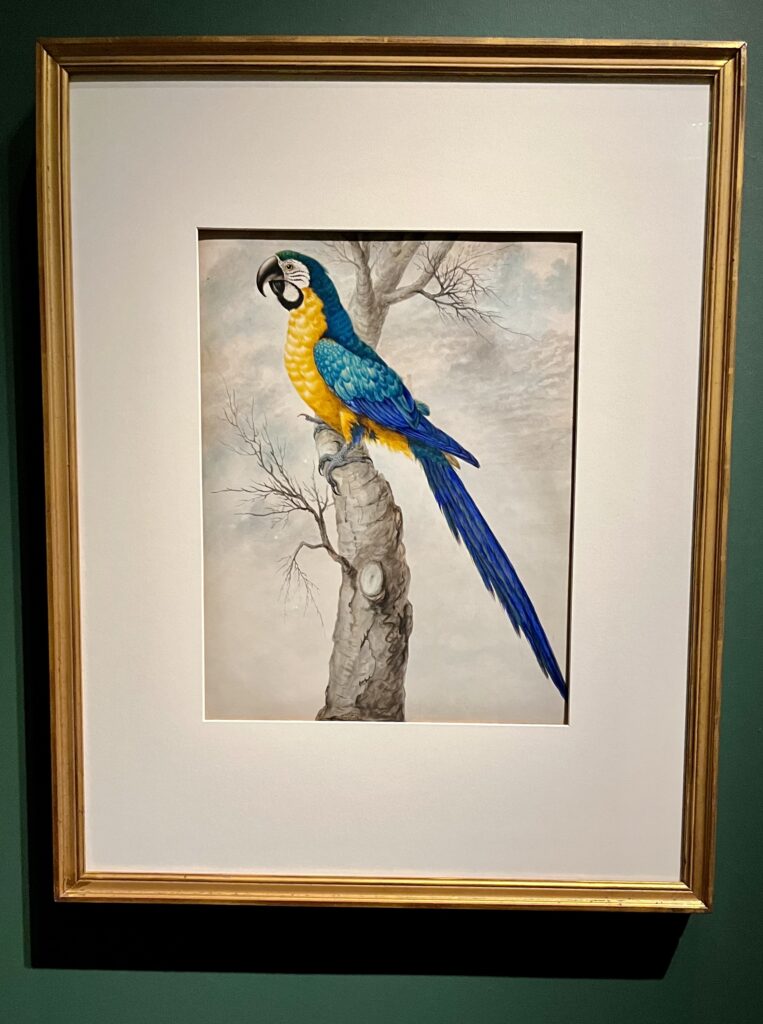

- Blue and Yellow Macaw, c. 1789, by Sarah Stone, later Sarah Smith, a British natural history painter and illustrator whose works, as well as having strong visual appeal, are significant as scientific documentation of now-lost specimens.

Collateral to the exhibition

The BMA Shop has done a terrific job of sourcing gifts and publications, especially books, relevant to historic women artists. Visitors may well wish to acquire the show’s beautifully produced exhibition catalogue, which is on sale in the museum store. And Art Herstory is honored to be represented in this elegant emporium! Read here about the Art Herstory note cards, holiday cards, magnet and porcelain ornament that the BMA Shop carries to complement Making Her Mark.

Not on offer in the store, at least not at the time of our visit in late October, are the inaugural volumes in the series “Illuminating Women Artists.” The volumes focus on Luisa Roldán, Artemisia Gentileschi, Elisabetta Sirani, and Rosalba Carriera, all of whom are well represented in the show. But, North American readers can source these affordable, generously illustrated books from Getty Publications; and book buyers in other regions can acquire them from Lund Humphries. There are two more series volumes forthcoming in Spring 2024, which also feature artists in Making Her Mark: Sofonisba Anguissola and Louise Moillon.

Going into the exhibition, we thought we might see works on loan from Baltimore’s other world-class art museum, The Walters Gallery. The Walters owns paintings by Barbara Longhi, Sofonisba Anguissola, Lavinia Fontana, and Josefa de Ayala (also called Josefa Ayala, Josefa de Óbidos); and enamelwork by Suzanne de Court. But these works can participate in only one venue of the exhibition, and of course it makes sense to prioritize access for Canadian audiences. Visitors to and residents of Baltimore can normally see the works at their home institution, where they are on permanent display, and where there is no entry fee.

Conclusion, and a final challenge

Before opening, Making Her Mark: A History of Women Artists in Europe, 1400–1800 was hailed by Vogue as a “must-see” exhibition and branded a “sure-to-be-historic show” by The New York Times. That’s some significant hype to live up to; but that’s one more challenge that the show has met! “Tour de force” is not a term to throw around lightly, but we are going to use it here: Making Her Mark is a tour de force. It is visually magnificent; and it succeeds in dismantling artistic hierarchies, highlighting collaborations, and recognizing and celebrating intersections and continuities from the Renaissance to the present.

Sèvres (Hillwood Estate, Museums & Gardens). Right: Still Life with Parrot, 1661, by Maria-Theresia van Thielen (Milwaukee Art Museum). Photo, Mitro Hood.

The final challenge we’ll point out is one for future art exhibitions that survey multiple centuries, whether or not they focus on women artists: Making Her Mark is a hard act to follow.

Want to know more?

As we note above, there’s more to say about Making Her Mark than any one review can cover. We encourage readers to explore coverage by other reviewers. Here are links to the open-access reviews we know of: Bmore Art; Art & Object; Pundicity (also appeared in the Wall Street Journal); Forbes.com; Catholic Review; Modern Vasari; and Antiques and the Arts Weekly.

Making Her Mark: A History of Women Artists in Europe, 1400–1800 is on at the Baltimore Museum of Art through January 7, 2024. It moves to Toronto in Spring 2024, where it will run at the Art Gallery of Ontario from March 27 through July 1.

Erika Gaffney is Founder of Art Herstory. Follow Erika on Bluesky, LinkedIn and Facebook.

More Art Herstory exhibition reviews:

Roma Pittrice: Women Artists at Work in Rome Between the Sixteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, by Alessandra Masu

Female Artists and their Remarkable Careers: An Appeal to Rethink Art History, by Jenny Körber

Women Artists at the Cape Ann Museum, by Erika Gaffney

Making Her Mark Leaves its Mark at the Art Gallery of Ontario, by Isabelle Hawkins

Early Modern European Women Artists at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, by Erika Gaffney

Making Her Mark, An Essential Corrective in the History of Art, by Chadd Scott

Carlotta Gargalli 1788–1840: “The Elisabetta Sirani of the Day,” by Alessandra Masu

Masters and Sisters in Arts, by Jitske Jasperse

Marie Laurencin: Sapphic Paris, A Review, by Alice M. Rudy Price

Material Re-Enchantments: A Review of Remedios Varo: Science Fictions, by Suzanne Karr Schmidt

Sofonisba Anguissola in Holland, an Exhibition Review, by Erika Gaffney with Cara Verona Viglucci

Rosa Bonheur—Practice Makes Perfect, by Ien G.M. van der Pol

The Ladies of Art are in Milan, by Cecilia Gamberini

In defense of monographic exhibitions of female artists: The case of Fede Galizia, by Camille Nouhant

So interested to read about this, Erika and pleased to see that at least one of the artworks is from the Fitzwilliam in Cambridge! Very much hope that the exhibition makes its way to the UK in due course.

Thanks, Ann! I don’t know that there are plans for this particular show to move to the UK, but (as you may well know) there are at least these two UK shows featuring premodern women to which to look forward in 2024: Angelica Kauffman at the Royal Academy, and Women Artists in Britain, 1520-1920 at the Tate Britain. Exciting times!