Guest post by Sandy Rattley, Audacious Women Productions

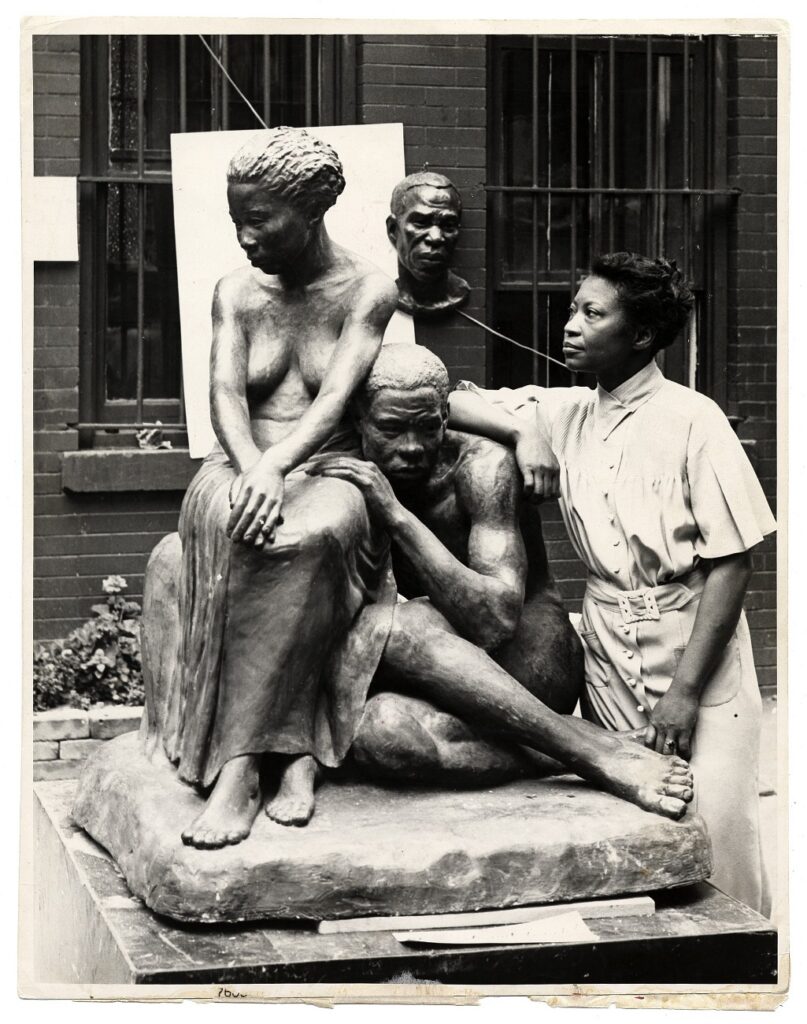

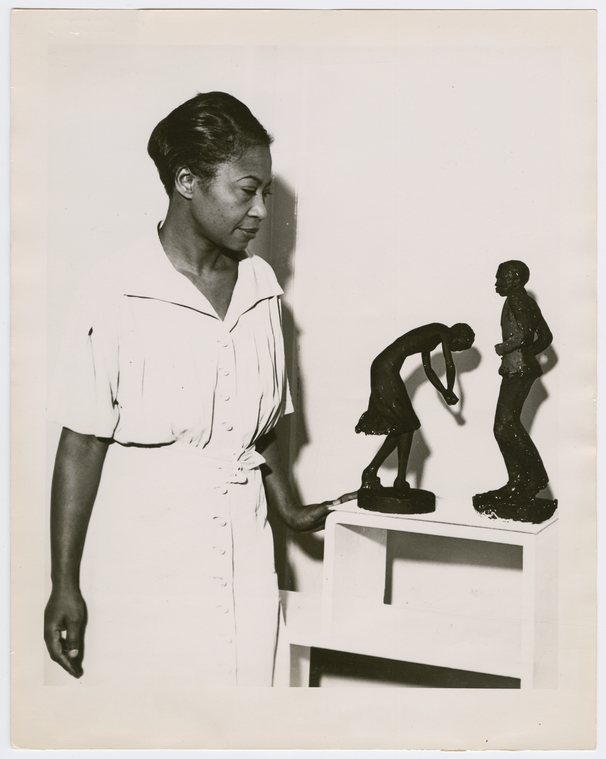

Augusta Savage is an amazing woman who undoubtedly fits the description of “audacious,” as she overcame countless odds to accomplish many firsts in her life.

Determined to be an artist

Born in 1892 in Green Cove Springs, Florida, Augusta Savage had a strong desire at a very young age to be an artist and work with clay, a pastime that both her parents vehemently opposed. Her father was a Methodist minister who saw the animals she made as sinful graven images. Describing her early years, Savage said in an interview that she got numerous beatings every day for making things with red clay and that her parents “practically whipped the art out of [her].” Despite her parents’ resistance, thankfully, she persisted.

Initially self-taught, she entered several works in the 1919 West Palm Beach County Fair: a bust of former West Palm Beach Mayor George Graham Currie; her interpretation of a wild stallion she modeled using a donkey; the Virgin Mary; and a few religious statues. She exhibited her work between stalls of farm animals, fruits and vegetables. There was no category for art, but Savage won a blue ribbon and $25 prize. Her passion and promise were so contagious that the fair’s attendees spontaneously took up a collection to support her dream of becoming an artist and to send her to New York.

A “leading light”* of the Harlem Renaissance

Before moving to New York City, Augusta Savage spent time in Jacksonville, Florida trying to convince “wealthy Negroes” to have busts made. But that plan did not pan out. In 1921, Savage took a train from Jacksonville to the Big Apple wearing a homemade coat, with $4.50 in her purse. After completing a 4-year art course at Cooper Union College of Art in three years, she became one of the leading influencers of the Harlem Renaissance. Savage was heralded as one of the most talented artists of the time period. She was called “Sculptress of the Negro People” because she centered Black life in her work.

She opened the first gallery dedicated to the exhibition of Black art in 1939.

While Black women were active in anti-lynching campaigns and the suffrage movement, Savage is one of the first women art activists in the early 20th century who fought to advance opportunities for Black artists and their inclusion in the mainstream art canon. She mentored a generation of African American art makers—such as Romare Bearden, Jacob Lawrence, Selma Burke, William Artis, and Norman Lewis—who subsequently became some of America’s most revered artists. Savage also founded several organizations to provide free art education to over 2,500 people.

Savage got a big break as the only Black artist, and one of four women, commissioned to create an exhibit for the 1939 World’s Fair in Flushing, NY. She decided to create a tribute to her friend from Jacksonville, Florida, former NAACP head and poet, James Weldon Johnson, who had composed the lyrics for the Black National Anthem, “Lift Every Voice and Sing.” Augusta Savage took over a year to create a 16-foot sculpture depicting a choir of 12 Black children singing, arranged like strings on a harp held up by the hand of God.

Savage was so determined that when some of the models she had contracted to pose for her 2-story sculpture didn’t show up, she went out on the streets of Harlem and recruited people to take their place.

Her monument to Black culture and Black resilience, also known as The Harp, was among the fair’s most visited and photographed exhibits, seen by more than five million people. Yet tragically, Lift Every Voice and Sing was bulldozed when the Fair closed, as Savage was not able to raise the funds to transport and store it, or have it cast in durable materials.

More than half of the 160 works of art Savage created are missing or have been destroyed, and none of her monumental large-scale works have survived.

Was Augusta Savage erased/canceled from the art market because she was an activist?

Augusta Savage was consistent in her fearlessness, protesting against an incident she experienced in 1923, when she was accepted, and then rejected from participation in a prestigious art fellowship in Paris because of her race. Savage initiated a letter writing campaign and protested her rejection in editorials and interviews in mainstream media. She also resisted sexism, even from some of her Harlem Renaissance peers, such as scholar Alain Locke, a leading figure in the “New Negro Movement” who questioned Savage’s academic credentials and why she was the subject of so much media attention. Also, because of her involvement with Black identity movements such as the United Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) and other progressive causes, Savage was the target of an FBI investigation. But these challenges did not deter her art activism or her art practice.

An open question is whether Savage’s activism and artistic choices stereotyped her in the eyes of museum curators, reviewers and art buyers of her time, resulting in her erasure – her accomplishments being contested, and her art not being preserved. But some scholars suggest that Savage was likely impacted by the dominance of men in the art world that is still inherent in museums and art culture today. The fact that so little of her work is in the permanent collections of museums and available to the public is consistent with the fact that Black women continue to be the least represented in the art marketplace. As reported in the 2022 Burns Halperin Report, between 2008 and 2020, work by female-identifying artists constituted just 11% of acquisitions. The same source indicates that 14.9% of exhibitions at U.S. museums, while only 2.2% of acquisitions, and 6.3% of exhibitions were by Black American artists. According to that report, just 0.5% of the art in museums’ permanent collections are the work of Black American women.

Augusta Savage had tremendous resolve and commitment. Her sense of self-determination and mission are legendary, especially for a young Black woman from the South in the 1920s. She has been called a “waymaker” for confronting racism and making a way where no road existed, and for her dedication to creating careers in the arts for so many Black artists and aspiring artists. Her legacy of art education, and her experiences and accomplishments countering under-representation in the art world, still resonate today.

*Quote from artist and Savage Mentee Jacob Lawrence

Sandy Rattley is the co-executive producer, writer and director of the 22-minute biographical documentary Searching for Augusta Savage, the lead film for the new PBS series American Masters Shorts. The film can be accessed on the American Masters YouTube channel, as well as PBS.org. To counter the fact that much of her art is not available to be exhibited today, Rattley and her production partner Charlotte Mangin collaborated with new technology artists to create and animate interpretations of Savage’s most impressive lost work of art, Lift Every Voice and Sing, the sculpture she created for the 1939 World’s Fair which is reconstructed in the Searching for Augusta Savage film. Informed by Savage’s own words and writings, major moments in Savage’s childhood for which no archival or visual documentation exists are also recreated in the film—including the clay ducks that were the first art that Savage created as a child, as well as the story she told of her birth on February 29 in a leap year. The voice of Augusta Savage is brought back to life in the film through readings by actor Lorraine Toussaint of Savage’s own words pulled from quotes in newspaper clippings, and excerpts from a 5-page interview Savage conducted with the Federal Art Commission in 1935. Rattley states that digital reconstruction of Savage’s missing monument, as well as the scenes of creative impetus in her life, are powerful tools for remembrance, helping to reverse Savage’s historical erasure. A director’s cut of the film with a bonus scene that investigates Savage’s legacy of arts education in her hometown, Green Cove Springs, Florida, is available for screenings at community events and conferences. Contact Audacious Women for more information. Free, standards-aligned educational resources for grades 6 through 12 based on the Searching for Augusta Savage documentary are also available on PBS LearningMedia.

More Art Herstory blog posts you might enjoy:

Sculpture or Suffrage: Alice Morgan Wright, by Jennifer Dasal

A Quiet Eye—The Unique Achievement of Sylvia Shaw Judson, by Rowena Loverance

The Cheerful Abstractions of Alma Thomas, by Alexandra Kiely

Visual Feasts: The Art of Sarah Mapps Douglass, by Erika Piola

Frida: Beyond the Myth at the Dallas Museum of Art, by Olivia Thomas

Esther Pressoir: Imagining the Modern Woman, by Suzanne Scanlan

Women Artists from Savannah at the Telfair Academy Museum, by Julie Allen

Science, Nature, and Music in the Art of Alma Thomas, by Erika Gaffney

The Life and Art of Dorothea Tanning, by Victoria Carruthers

Deirdre Burnett: A Significant British Ceramic Artist Remembered, by Jo Lloyd

Dalla Husband’s Contribution to Atelier 17, by Silvano Levy