Guest post by Haley S. Pierce, Assistant Curator of European Art, Eskenazi Museum of Art at Indiana University

While the Impressionist painter Claude Monet is well known, many people are unaware that his stepdaughter and daughter-in-law, Blanche Hoschedé-Monet (1865–1947), was also a successful artist. Opportunities to see her work are limited, and the few published accounts on Hoschedé-Monet discuss her only in connection to Monet. Although Hoschedé-Monet’s life and circumstances were inseparable from her stepfather’s, reliance on biography has hindered further study of her work. The exhibition Blanche Hoschedé-Monet in the Light and its accompanying catalogue seek to better understand the scope of Hoschedé-Monet’s career by analyzing her ambitions as an artist who also forged her own path.

The Other Artist in the Monet Family

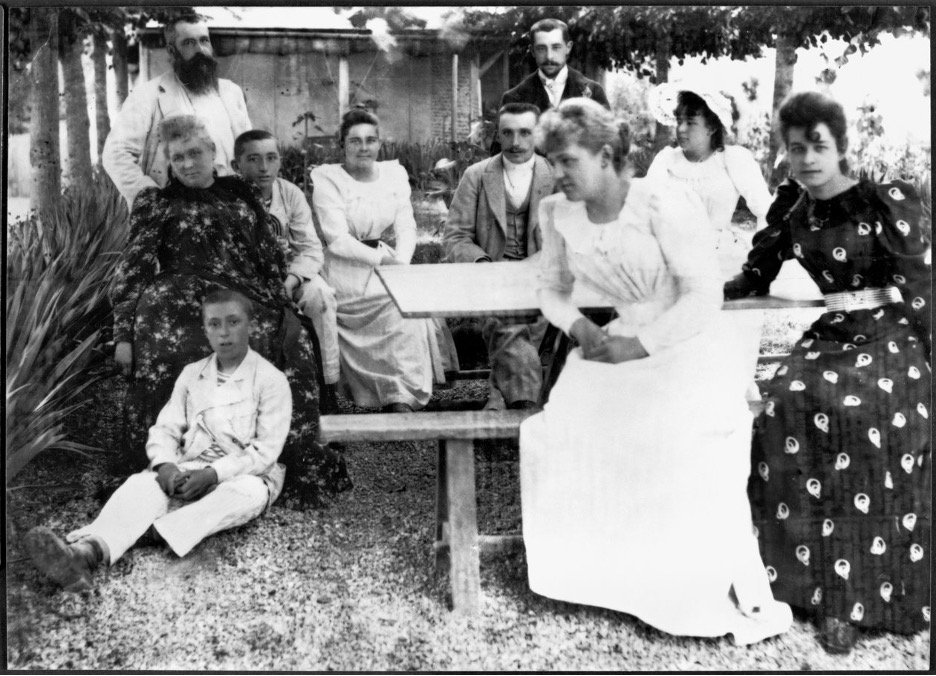

From childhood, Hoschedé-Monet was surrounded by works of modern art, having grown up at the center of the Impressionist movement. Her parents, Ernest and Alice Hoschedé, were important collectors and patrons. Family outings and dinners even consisted of visits with renowned artists like Édouard Manet and Auguste Renoir. In 1876, the Hoschedés commissioned Monet to paint a series of decorative panels for their home. And later, when faced with financial difficulties that forced the sale of their estate, the Hoschedés took refuge with the Monet family. Following Camille Monet’s death in 1879 and Ernest Hoschedé’s estrangement from his family, Claude Monet and Alice Hoschedé remained together and moved their children to Giverny in 1883, when Hoschedé-Monet was seventeen years old.

Hoschedé-Monet began to paint in earnest in Giverny, accompanying Monet on his en-plein-air painting expeditions in the surrounding countryside. While she focused on many of the same motifs as Monet during this early period, Hoschedé-Monet’s compositions were often unique, depicting different points of view. In 1897, she married Monet’s eldest son, Jean, and the couple moved to Rouen.

This period of relative independence from her family and Monet marked a turning point in Hoschedé-Monet’s career. In 1905, she began exhibiting her work at the Salon des Indépendants in Paris. Having joined a professional network of artists in Rouen, she participated in the inaugural Salon de la Société des Artistes Rouennais in 1907. Though she would exhibit frequently over the next six years, her husband’s health rapidly declined, and they returned to Giverny in 1913. Jean Monet died the following year, and Hoschedé-Monet moved back in with Claude Monet to care for the family property and her aging stepfather, who had been widowed since 1911.

Later Years and Reputation

During this period, Hoschedé-Monet put her career as an artist on hold. According to her younger brother, Jean-Pierre Hoschedé, she completely stopped painting until after Monet’s death in 1926. But as Nancy Mowll Mathews surmises in her catalogue essay “The Painter Hits Pause: Examining Blanche Hoschedé-Monet’s Hiatus, 1912–1926,” this would account for a lapse of nearly fourteen years. Such a defined break seems unlikely, especially because Hoschedé-Monet would hold her first solo exhibition in 1927, at the Galerie Bernheim-Jeune in Paris, not even a year after Monet’s death.

Though Hoschedé-Monet continued exhibiting at important venues and had three further solo exhibitions before her death in 1947, her achievements are relatively unknown today. This includes the extent to which she ensured Monet’s legacy through negotiating the permanent installation of his Water Lilies at the Musée de l’Orangerie, or her protection of his home and gardens in Giverny during World War II.

In addressing the question of why Hoschedé-Monet and her work have largely been overlooked, Jean-Pierre Hoschedé wrote in 1960: “a) because Blanche Hoschedé never had the slightest ambition; b) because being Claude Monet’s daughter-in-law was precisely why she never benefitted from his protection, nor from the great name that also became hers; c) because she painted solely for her own pleasure.” But as Galina Olmsted demonstrates in her catalogue essay, “Peintre impressioniste,” Hoschedé-Monet certainly was not unambitious, as shown by her extensive exhibition history alone. And the notion that she painted only for her enjoyment downplays the seriousness of her dedication to her art. This characterization is perhaps telling of a gendered bias that was pervasive during her lifetime, when it was less (though becoming increasingly more) common for women artists to pursue professional opportunities.

The Making of Blanche Hoschedé-Monet in the Light

Described in biographical accounts as extremely humble and modest, Hoschedé-Monet did not write about her own work, and only a few published letters and notes remain. Through an examination of her exhibition record and sales history, as well as chronological analysis of her paintings, Blanche Hoschedé-Monet in the Light attempts to illuminate Hoschedé-Monet’s aims and career by taking measure of her success.

Recognizing Hoschedé-Monet’s Ambition

Much of the research for this project relied on information gleaned from important secondary sources. For example, from a letter written by Monet to Alice Hoschedé, we know that Hoschedé-Monet first attempted to submit a painting to the Salon des Artistes Français in 1888 with Monet’s encouragement, though it was rejected. We know, too, that Hoschedé-Monet had begun to attract attention as a young painter working within the artist colony at Giverny.

As early as 1890 she was thinking about her painting seriously, having started a carnet des comptes, listing works for sale and exhibition as noted in Mathews’s “The Painter Hits Pause.” In 1892, fellow artist Theodore Robinson mentioned in a diary entry that Hoschedé-Monet had “improved greatly,” and that she had sold a painting to the prominent Impressionist collectors Bertha and Potter Palmer. Julie Manet (daughter of Berthe Morisot and niece of Édouard Manet) also described the “lovely color” of Hoschedé-Monet’s paintings after visiting Giverny in 1893.

Monet’s evident support of Hoschedé-Monet also shows that he held her work and interests in high esteem. He depicted her in the act of painting in multiple studies, identifying her as an artist (like in this work at LACMA). And he even brought her into the fold of his artistic milieu, taking her to exhibitions and introducing her to colleagues. As Philippe Piguet recounts in his catalogue essay, “In the Light of Claude Monet,” Monet accompanied Hoschedé-Monet to the Salon du Champ-de-Mars in 1891 in Paris. Later that year, she and Monet called on James McNeill Whistler and John Singer Sargent in London. She describes the visit in a letter to her mother, noting that they saw Whistler’s famous Peacock Room designed for Frederick Leyland.

Reevaluating Hoschedé-Monet’s Career

Hoschedé-Monet’s early exhibition history illustrates her work’s positive reception, especially during her productive years in Rouen. But the fact that she continued exhibiting and was offered four solo exhibitions after her alleged return to painting in 1926 (when she was in her sixties) shows that she remained well regarded. As Nicolas Bondenet notes in his catalogue essay, “The Last of the Impressionists,” Hoschedé-Monet’s popularity increased exponentially following Monet’s death. After 1926, the Galerie Durand-Ruel purchased her paintings for ten times the amount of previous acquisitions, indicating her success. This documented achievement during her lifetime makes her later drift into obscurity even more confusing.

Curating the Exhibition

Beyond filling important gaps in the scholarship on Hoschedé-Monet, curating this exhibition and creating its comprehensive checklist presented numerous challenges. As many of Hoschedé-Monet’s paintings remain in private collections, opportunities for seeing them are rare. Only a small number are held in museums in France (namely, the Musée Blanche Hoschedé-Monet). And there is just one known painting in a public collection in the United States (Columbus Museum of Art).

Perhaps the largest challenge, however, was understanding the chronological order of Hoschedé-Monet’s paintings, as many are undated and untitled. Though stylistic differences can sometimes be discerned between her early and late work, mapping Hoschedé-Monet’s output over the length of her career required much research. For example, we can match many works with locations where Hoschedé-Monet lived and visited, and the associated dates. For other paintings, we can assign approximate dates based on their subject’s comparison to similar canvases by Monet, when the two worked alongside each other in Giverny.

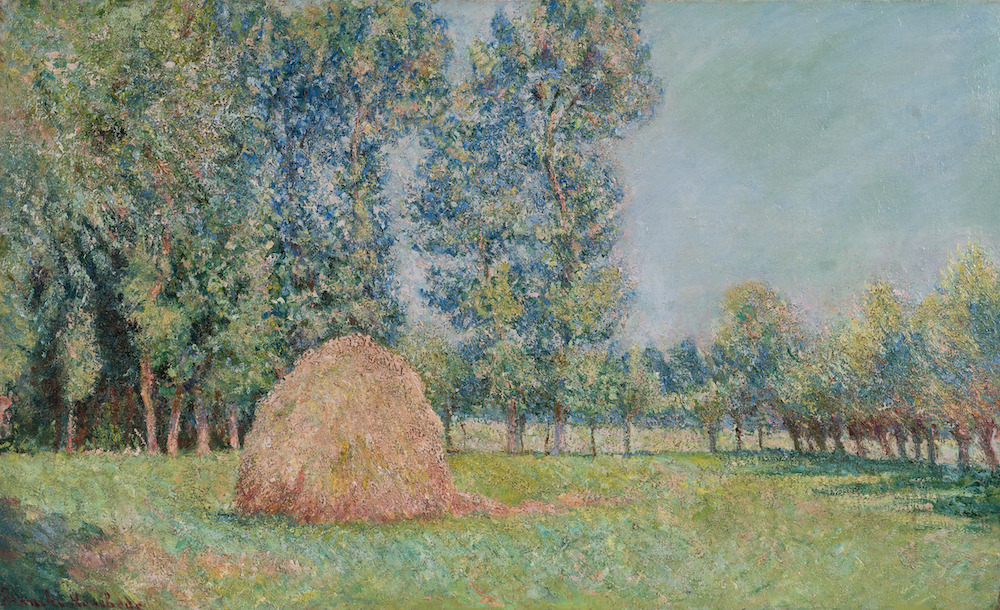

One such artwork is Hoschedé-Monet’s Haystack at Giverny, which appears to portray the same subject as seen in a painting by Monet from 1893, though from a different angle. Another example is Hoschedé-Monet’s Morning on the Seine, which corresponds to a series of paintings begun by Monet in 1896. Hoschedé-Monet’s previously undated Ice Floes at Vernon depicts the Seine in comparable purples and blues to Monet’s paintings of the same winter scene from 1893, such as in the collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

New Discoveries

Research continued even during the installation of the exhibition, when I was able to see many of the paintings for the first time in person. I discovered that several of Hoschedé-Monet’s canvases are unvarnished, allowing for the rare chance to see the paintings and their colors in nearly original states. Bright blues, greens, and purples abound, showing Hoschedé-Monet’s affinity for color. The preserved texture of her paint-loaded brushstrokes also provides insight into how she may have worked. Inspection of Hoschedé-Monet’s The Garden of Giverny (The Path under the Rose Arches) (Musée Clemenceau) revealed small, intact curls of dried paint. This condition is especially uncommon given the paint’s fragility, but also because such texture is often concealed behind layers of varnish. Bits of debris embedded in the paint layers of some works —perhaps left behind from days spent working outside en-plein-air—are also visible.

To my excitement, I uncovered new dates and subjects when studying certain works up close. For example, Hoschedé-Monet’s The Garden of Giverny (The Path under the Rose Arches), which was previously undated, can now be assigned to 1927. The artist appears to have added the date “27” next to her signature in bright red paint, which is barely visible against the background of flowers. Finally, a new title can be given to a small canvas formerly referred to as View of Lake Bourget (thought to portray the location near the Swiss border that Hoschedé-Monet visited in the 1930s). Closer examination proved that the painting actually depicts the Mediterranean near Nice, with the rocky outcropping of Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat visible in the distance.

Research is ongoing, and there is still much we need to do to expand the narrative of Blanche Hoschedé-Monet’s life and work. It is my hope that this exhibition and its catalogue will stimulate public interest in this significant artist and her contribution to the history of modern art.

Blanche Hoschedé-Monet in the Light is on at the Eskenazi Museum of Art at Indiana University through June 15, 2025.

Author biography

Haley S. Pierce is a Curator, Art Historian, and PhD Candidate at Emory University, specializing in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century European art. Prior to curating Blanche Hoschedé-Monet in the Light at the Sidney and Lois Eskenazi Museum of Art, she was the Curatorial Research Assistant in the departments of European Paintings and Drawings & Prints at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where she worked on Manet/Degas (2023). She has also held curatorial positions at the High Museum of Art, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, and the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Other Art Herstory blog posts you might enjoy:

Blanche Hoschedé-Monet: An Artist in Her Own Right, by Rebekah Hoke Brown

Charlotte Eustache Sophie de Fuligny-Damas, Marquise de Grollier, by David Pullins

Madeleine Françoise Basseporte’s Hyacinths at the French Court, by Mary Creed

Rosa Bonheur—Practice Makes Perfect, by Ien van der Pol

Louise Moillon: A pioneering painter of still life, by Lesley Stevenson

Madeleine Françoise Basseporte and the Ribbon as a Signifier of a “Woman’s Touch,” by Tori Champion

The Abstract-Impressionism of Berthe Morisot and Joan Mitchell, by Paula Butterfield

Marie Laurencin and the Autonomy of Self-Representation, by Mary Creed

Marie-Thérèse Reboul Vien: Finding the Natural in the Neoclassical, by Tori Champion

The Many Faces of Suzanne Valadon, by Suzanne Singletary

Victorine Meurent, More than a Model, by Drēma Drudge

The Theatrical Wonders of Jeanne Paquin’s Belle Époque Parisienne, by Julia Westerman

Marie Laurencin: Sapphic Paris, A Review, by Alice M. Rudy Price