Guest post by Suzanne M. Scanlan, Rhode Island School of Design

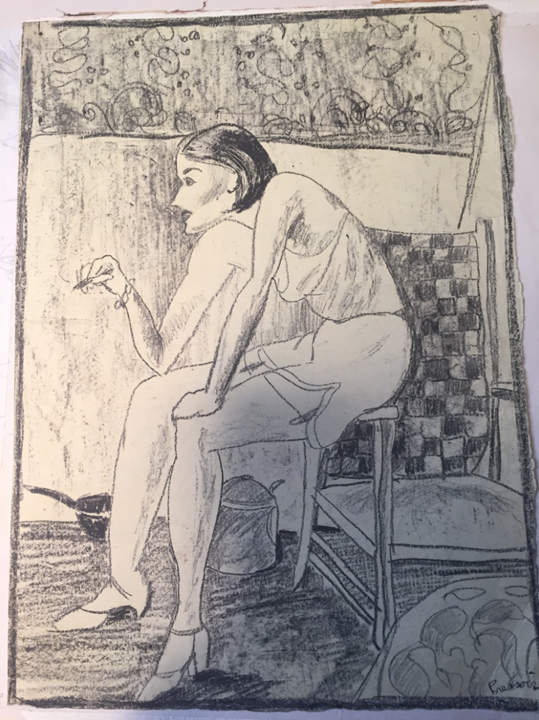

A yellowing, jagged-edged drawing simply titled “Sally,” by the American artist Esther Pressoir, gives us an intimate view of an unguarded moment. Perched on the arm of a wood-framed chair, the eponymous Sally leans forward to rest her weight on her bent knees. We see her in profile; her fashionably bobbed hair is tucked behind her ears, her cheeks are rouged and her lips painted. She wears a bandeau bra and tap pants, with silk stockings suspended by garters and secured by T-strap shoes. A single beaded bracelet encircles her right wrist, setting off the burning cigarette that she presses between her forefinger and thumb.

Made in 1927 or early 1928, the drawing represents a moment of respite, reflection and sensual indulgence. It is also consciously au courant, signified by Pressoir’s rendering of Sally in “liberating” lingerie, unconstrained by body shaping corsetry. Here, I briefly sketch the relationship between Esther/artist and Sally/sitter in this drawing to comment on modernist fashioning of the female body in the post-WWI era.

Who is Esther Pressoir?

Esther Estelle Pressoir (1902–86) was the daughter of French Canadian immigrants who made their living in the bustling textile mills of Woonsocket, RI. She won a scholarship to the Rhode Island School of Design, graduating from the department of painting and drawing in 1923. Settling in Greenwich Village, Pressoir studied at the Art Students’ League in New York and, during summers, with the progressive Provincetown Art Colony. During her long and prolific career as a painter, printmaker and ceramicist, Pressoir’s work was exhibited in, and purchased by, galleries and museums across the United States, and her stylized spot drawings were regularly featured in The New Yorker magazine.

When Esther Met Sally

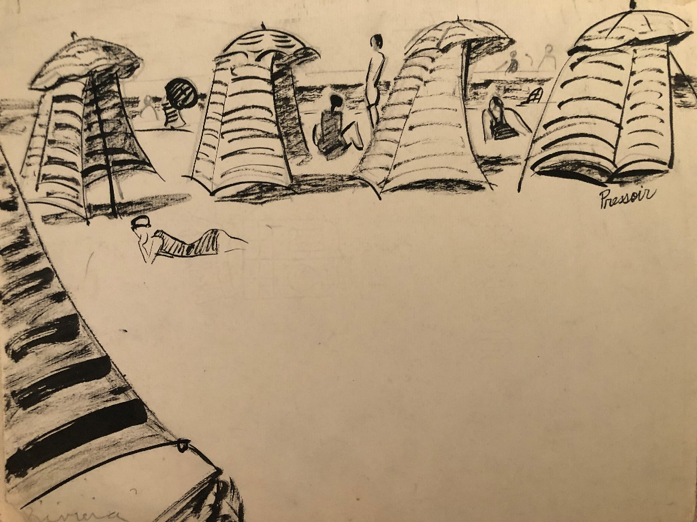

In July 1927, fresh out of art school and on a dare from fellow artists, Esther Pressoir embarked on an unprecedented, transformative seven-month bicycle trip across Europe to prove she could “do” The Grand Tour on a not-so-grand budget. In her words: the object of this trip was to become strong, cover ground, see the world & get a lot of sketching in on the money & time I had—both limited. She was accompanied by two different women on this journey: Helen, a fellow artist and long-time friend, and the mysterious “B,” a Cuban-born beauty who joined Esther’s cycling odyssey somewhere in France (after Helen departed) and remained with her all the way to Rome. Keeping handwritten journals and making hundreds of sketches along the way, Pressoir honed an economy of visual language and distillation of character and place that would define her artwork for decades.

We don’t know precisely when or where Esther and Sally met. Entries in Pressoir’s travel journal tell us that the two women planned to meet at a seaside villa on the French Riviera sometime in August of 1927. Sally was to make her way to Bandol from Paris. “B” would sightsee in Avignon while Esther joined Sally for a week of sketching and sunning by the shore. Whether the drawing was made at a villa in Bandol or in Sally’s flat in Paris is difficult to determine. However, the sketch was torn from a drawing pad Esther carried in her travel satchel, so we know that Sally posed for Esther at some point during her European sojourn.

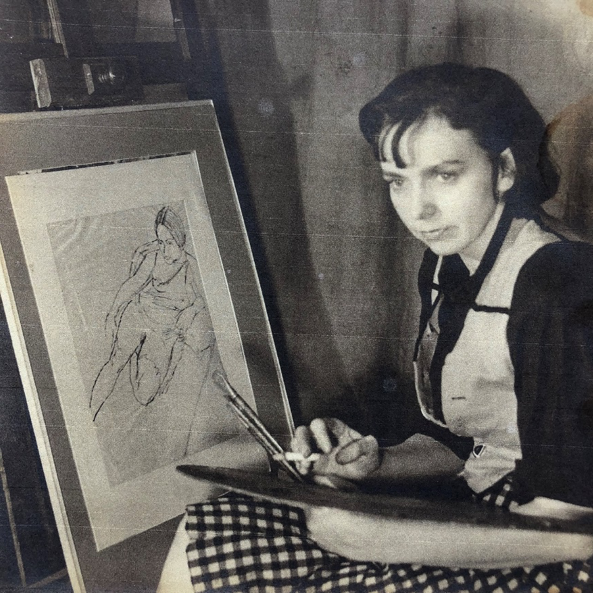

In a photo taken on the eve of her bicycle trip, Pressoir fashioned herself as Modern American woman and artist. Today, Pressoir’s smoldering cigarette is the most jarring element of the photo. We bristle at the thought of hot ash dropping into flammable paint or singeing paper drawings in the studio. Yet, 1920s advertisements pedaling cigarettes to women presented another story. Smoking was glamorous and chic.

Women who smoked were branded as independent, adventurous and high spirited. Amelia Earhart smoked! Josephine Baker smoked! Esther Pressoir smoked. Sally smoked. Indeed, contemporary critics declared that women who smoked, wore their hair short and dressed in “pajamas” or sportswear increasingly resembled their male companions. For better or worse—depending on who you asked—women were acting like men!

In the photo of Pressoir above, she displays her gestural ink sketch of an unidentified model reclining on a pillow, swathed only in a sheer and somewhat ragged chemise that leaves her nipples and pubic hair clearly visible. Pressoir’s bold lines demarcate the figure’s essential form. She leaves one leg cropped at the ankles which both truncates the model’s body and extends it beyond the picture frame. At the same time, the figure is almost crammed into the pictorial space, with her head bumping against one corner of the frame. Indeed, Pressoir is similarly cropped in the photo—artist and model share equal billing.

Setting the Stage for Sally

The tight space and discordant, almost theatrical, setting of Pressoir’s drawing of Sally suggests an artist’s studio, with patterned textiles (curtain, tablecloth) and still-life objects (a saucepan, a jug) strewn about, as if props waiting to be staged. Cast in this light, Sally assumes the role of an artist’s figure model who has paused to relax and smoke during a break in an arduous posing session. Her lithe body dominates the pictorial space. Her elongated limbs are deftly delineated in confident, unbroken strokes from Pressoir’s waxy crayon. There isn’t a hint of modesty or reticence in Sally’s posture; her legs are spread apart with both feet planted firmly on the floor. Completely at ease, she claims space and agency with every exhalation of smoke from her ruby lips.

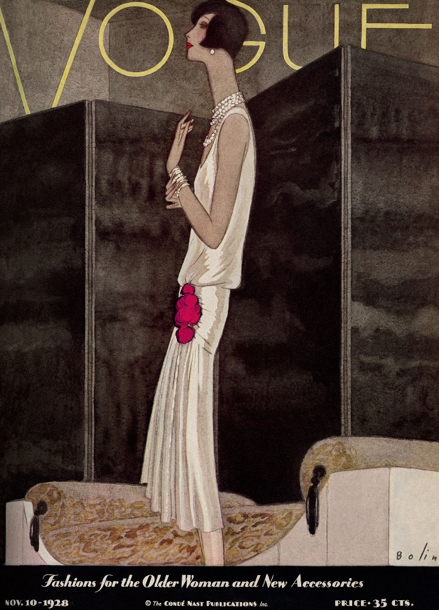

In the aftermath of WWI, the turn-of-the-century ideal of the voluptuous, curvaceous woman gave way to a sinuous, smooth, “modernist” silhouette. Fashion illustrations made for Paris couturiers such as Paul Poiret, Madeleine Vionnet and Jeanne Lanvin portray slender, hipless figures known as la garconne (the boyish woman). Restrictive corsets gave way to loose undergarments and elaborate hairstyles were cut short. Sportswear made of washable, breathable fabric was introduced (particularly by Coco Chanel) resulting in what historian Mary Louise Roberts deemed the “visual erasure of sexual difference” in fashion. Roberts went on to declare, “During the postwar period, fashion bore the symbolic weight of a whole set of social anxieties concerning the war’s perceived effects on gender relations….Feminists, designers (both male and female), and the women who put on the new fashions interpreted them as affording physical mobility and freedom. Because the new fashions were seen in this way—as a visual language of liberation—they also became invested with political meaning.”

Reframing the Corset

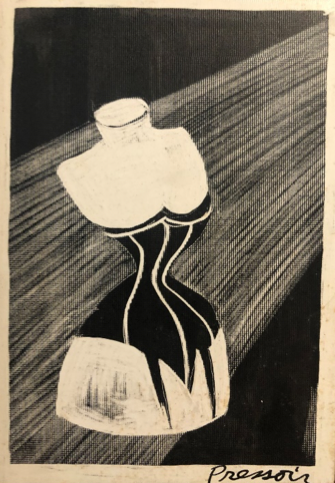

Esther Pressoir isolated the corset in a series of small scratchboard studies, some of which were submitted as potential spot drawings for The New Yorker magazine. In one, we see a headless, limbless mannequin molded into an exaggerated hourglass shape by a whalebone corset. Black garters drip from the corset’s hem like tentacles reaching for prey. The figure is illuminated by a shower of gleaming rays that render the truncated body morbidly translucent—a scathing comment by Pressoir on the constricting confines of the corset.

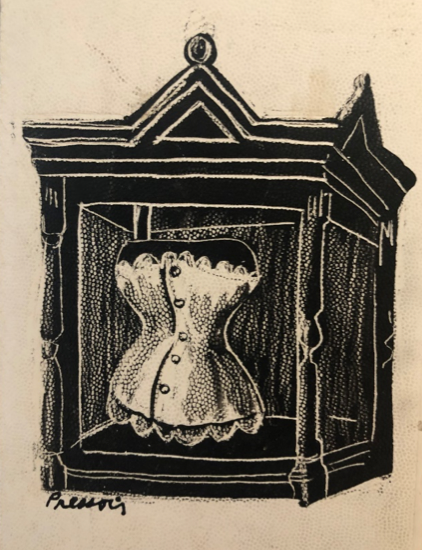

A second rendering shows a lace-trimmed corset encased in a glass-front box. The garment is buttoned up and starchily animated, enshrined in an architectonic tomb. Here Pressoir renders the corset as a relic of a bygone age, properly preserved for posterity.

By drawing Sally as la garconne in contemporary lingerie, then, Pressoir invested her with a liberated sensuality that subverted canonical representations of women imagined solely for the delectation of a male viewer. Paintings and prints created by Pressoir in the wake of her European travels were shaped by her keen observation and meticulous documentation of 1920s society and fashion along the way. Casting aside the corset and the social constraints they embodied liberated both artist and model in this moment, and launched the sense of style and stylization that would define Esther Pressoir’s artwork when she returned to New York the following year.

Dr. Suzanne Scanlan is an art historian and Senior Lecturer in Theory, History of Art and Design at RISD. She received her PhD in History of Art and Architecture from Brown University and is the author of Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi: Religious Women and Art in 15th-century Rome. Suzanne lives in Providence, RI. Her book Esther Pressoir: A Modern Woman’s Painter is forthcoming in Spring 2024.

Other Art Herstory blog posts you might enjoy:

Sculpture or Suffrage: Alice Morgan Wright, by Jennifer Dasal

Modern Women Artists in Copenhagen 2024–2025: Three Exhibitions, by Alice M. Rudy Price

Frida: Beyond the Myth at the Dallas Museum of Art, by Olivia Turner

A Quiet Eye—The Unique Achievement of Sylvia Shaw Judson, by Rowena Loverance

Nancy Sharp: An Undeservedly Forgotten Exemplar of Modern British Painting, by Christopher Fauske

Women Artists from Savannah at the Telfair Academy Museum, by Julie Allen

The Cheerful Abstractions of Alma Thomas, by Alexandra Kiely

Deirdre Burnett: A Significant British Ceramic Artist Remembered, by Jo Lloyd

Marie Laurencin: Sapphic Paris, A Review, by Alice M. Rudy Price

Susie M. Barstow: Redefining the Hudson River School, by Nancy Siegel

Evelyn De Morgan: Painting Truth and Beauty, by Sarah Hardy

Anna Ancher’s Vaccination and Scientific Motherhood, by Alice Price

Celebrating Eliza Pratt Greatorex, an Irish-American Artist, by Katherine Manthorne

Marie Laurencin and the Autonomy of Self-Representation, by Mary Creed

Dalla Husband’s Contribution to Atelier 17, by Dr. Silvano Levy

Thank you! I enjoyed this immensely.