From the Connoisseur’s Collection to the Global Museum Blockbuster

Guest post by Christopher R. Marshall, the University of Melbourne

Public religious art commissions played a vital role in promoting the careers of Italian Renaissance and Baroque artists. This was especially so prior to the establishment of the museum as a site of general public access from the eighteenth century. Artemisia Gentileschi was initially held back in this regard by her early collectors’ predilection for a limited range of female-oriented privately commissioned gallery paintings (Fig. 1). As a result she was largely overlooked when it came to the numerous possibilities for Roman ecclesiastical commissions that were on offer during the 1620s.

Artemisia in Naples

In 1630, however, this all changed following Gentileschi’s relocation to Naples at the invitation of the incoming Neapolitan viceroy. For the first time in her career Gentileschi was now the focus of significant public demand. Gentileschi’s appeal to the local Neapolitans lay in her ability to present herself as a sophisticated purveyor of modish artistic trends picked up during her recent residencies in Florence, Rome and Venice. This enabled her to win a series of religious contracts culminating in a commission for no fewer than three monumental altarpieces produced between 1635 and 1637 for the cathedral of Pozzuoli on the outskirts of Naples (Fig. 2).

Gentileschi’s 20th-century rediscovery

The twentieth-century rediscovery of Artemisia begins modestly enough in Roberto Longhi’s decision to feature her work in the landmark 1951 survey exhibition, Mostra del Caravaggio e dei Caravaggeschi. Here she maintained an only marginal presence via the inclusion of two versions of Judith. By contrast, her father, Orazio (who taught her to paint and was an early follower of Caravaggio), was allotted a dozen canvases and Caravaggio was given no fewer than 51 (although not all today recognised as by his hand). Another forty years was to elapse before Artemisia’s first retrospective exhibition held at the Casa Buonarroti, Florence, in 1991. This private house museum is worlds removed from the monumental scale and pressing crowds that characterise the Uffizi, Accademia or any of Florence’s other most visited museums. Its selection as the venue for her first retrospective thus suggests that, in the early 1990s at least, Gentileschi was a specialist topic of limited interest to connoisseurs only.

Artemisia in America

Gentileschi’s critical stocks were rising, however, thanks to the trans-Atlantic championing of her work by the American feminist movement. No fewer than six of her canvases were included in the 1976–77 influential survey exhibition Women Artists, 1550–1950. Curated by Ann Sutherland Harris and Linda Nochlin, this exhibition opened at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art before touring to four other American cities. Women Artists canonised Artemisia—literally in an art historical sense—by enshrining her as a key representative of a freshly minted canon of women’s artistic creativity. The results of this flattering presentation are evident in the photographic documentation of the exhibition’s installation at the Brooklyn Museum (Fig. 3).

Here the imposing scale and dramatic sweep of Gentileschi’s compositions have been used as a focal point in the exhibition’s opening rooms. Gentileschi’s early Susanna of 1610 and mid 1620s Detroit Judith (Fig. 4) have been given their own centrally positioned wall spaces and hung close to the floor.

This enables them to dominate the space and visually overshadow the smaller and more intimate works around them, including Sofonisba Anguissola’s self-portraits and Giovanna Garzoni’s still lifes. The curatorial emphasis on selecting some of her grandest and most dramatic canvases thus framed Gentileschi within the exhibition as the greatest—and by implication the only—exemplar of the canonical Female Italian Grand Manner. It presented her as the woman’s Raphael, Michelangelo and Caravaggio all rolled into one.

Orazio and Artemisia Gentileschi: Father and Daughter Painters

2001 marks a tipping point in Gentileschi’s subsequent progression from specialist focus to global blockbuster celebrity. In this year the Metropolitan Museum’s Keith Christiansen and Judith Mann from the Saint Louis Art Museum highlighted her work in a major international touring exhibition. Gentileschi was given the kind of authoritative art-historical presentation that her champions could only have dreamed of back in the 1970s. Artemisia’s canvases positively glowed in the spacious top-lit galleries of the Metropolitan’s installation as they were generously distributed along a carefully laid out itinerary leading the viewer through the various stages of her career (Fig. 5).

Some early reviewers were nonetheless critical of the museums’ decision to grant Artemisia the deluxe treatment of an international touring exhibition, but only on the condition that her works be viewed in relation to her father’s. The resulting exhibition—to give it its full title of Orazio and Artemisia Gentileschi: Father and Daughter Painters in Baroque Italy—tended, by its very nature, to conflate Artemisia’s career within that of Orazio’s. It allocated her a total of 34 paintings, whereas her father was given 50. This certainly improved upon the two Artemisias featured in the Mostra del Caravaggio e dei Caravaggeschi of 1951. Yet it remained the case all those years later that she was still not allowed to stand on her own two feet and in her own right.

Artemisia in London and Genoa: Discoveries and controversies

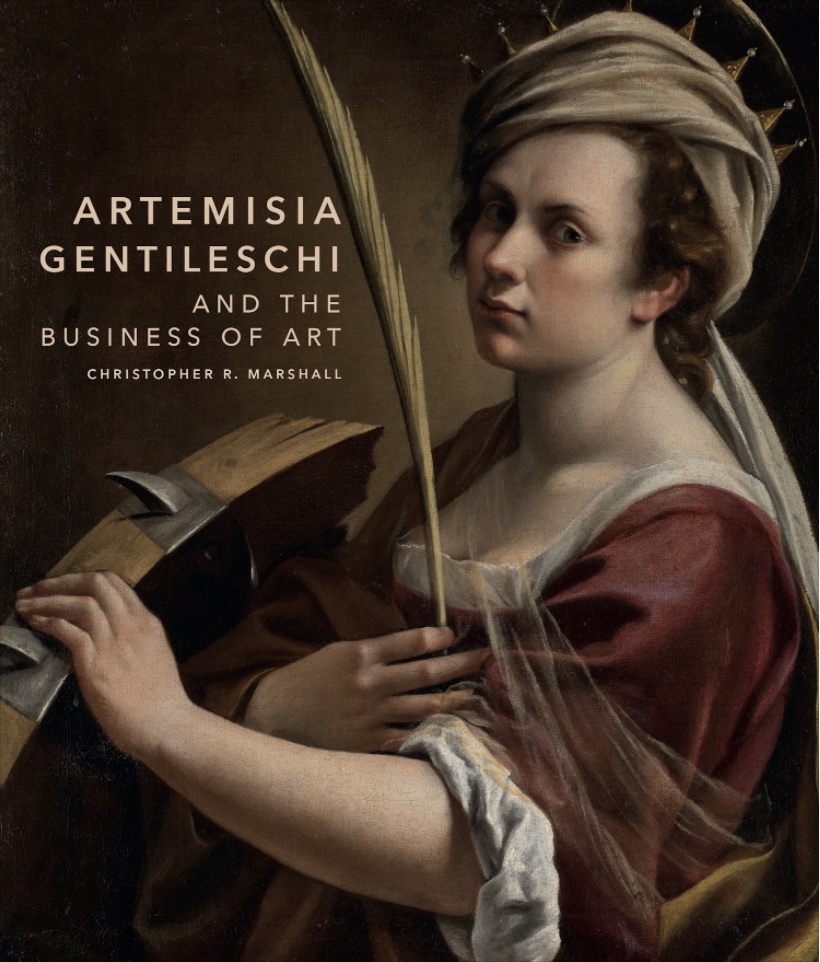

The wheel has now come full circle and Artemisia has become a proven museum box-office commodity. More than a dozen exhibitions featuring her name in the title have been held in locations as diverse as Paris, Pisa, Moscow, Milan, Conversano, Rome, Chicago, Hartford, Detroit, Olomouc (Czech Republic), Enschede (Netherlands), London, Naples and Genoa. The increased public attention attendant upon these multiple exhibitions has helped to stimulate demand for newly attributed works to appear on the market. The National Gallery, London’s 2020 retrospective exhibition benefited from this process. It included a freshly discovered masterwork, the Self-Portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandria, that had languished unnoticed for decades in a French private collection prior to being auctioned at the Hôtel Drouot, Paris, on December 19, 2017 (Fig. 6).

The painting sold for the then record price of €2.4 million/US $2,832,960, including premium and fees. It was then sold to the National Gallery, London, for £3.6 million/US $4.75 million. This made the St. Catherine the first painting by a woman artist to be acquired by the National Gallery since 1991. It was also one of a mere 21 artworks by women in the Gallery’s collection. In the space of three years, then, the St. Catherine had gone from being an unknown entity in a private collection to becoming a canonical addition to the oeuvre of one of the seventeenth century’s most important artists. Its acquisition, moreover, had helped redress the critical imbalance of women in one of the world’s most important museums. It accordingly figured prominently in the media commentary surrounding the 2020 exhibition, which also turned out to be the first major exhibition to be dedicated to a female artist in the Gallery’s 196-year history.

From November 16, 2023 to April 1, 2024, the Palazzo Ducale, Genoa, hosted its own Gentileschi blockbuster exhibition, Artemisia Gentileschi: corraggio e passione. This exhibition illustrates the high stakes and logistical complexities that are now attendant upon mounting exhibitions of this kind. It highlighted the difficulties involved in securing loans of Gentileschi’s works in an increasingly crowded field. One of its major works was the recently cleaned Conversion of the Magdalen from the Palazzo Pitti in Florence (Fig. 7). Yet this canvas was not on display during the exhibition’s opening weeks owing to its inclusion in another exhibition at the Casa Buonarroti from September 26, 2023 to January 8, 2024.

Life versus art

The exhibition also demonstrated the high degree of public scrutiny to which the biographical dimension of Gentileschi’s life-story is now subject. One of the exhibition’s most contentious components in this regard was a prominently situated multimedia gallery positioned at the exhibition’s half-way mark. This darkened and theatrically immersive space sought to evoke the violence and trauma involved in Gentileschi’s rape by the painter (and close colleague of her father) Agostino Tassi on May 6, 1611. It did so by juxtaposing a voice-over narrative of an actor recounting Gentileschi’s rape trial testimony of 1612 with a theatrical installation of the primal rape-scene bed, upon which were projected images of her paintings covered in blood (Fig. 8).

Tasteless in the extreme, the display was dubbed the “rape room” and publicly denounced by an alliance of students, artists, activists, curators and social-media influencers. The strong critical investment of these commentators in Gentileschi’s work, coupled with their readiness to speak out in favor of maintaining an appropriate balance in her curatorial presentation, speaks volumes for this artist’s extraordinary progression from little-known art historical footnote to transhistorical icon of female creativity.

Christopher R. Marshall is Associate Professor in Art History, Curatorship and Museum Studies at the University of Melbourne. His publications on Baroque art and the art market include Artemisia Gentileschi and the Business of Art (Princeton UP, 2024); Baroque Naples and the Industry of Painting (Yale UP, 2016); and chapter contributions to The Economic Lives of Seventeenth Century Italian Painters (Yale UP, 2010) and Mapping Markets in Europe and the New World (Brepols, 2006). His publications on museums and curatorship include Sculpture and the Museum (Routledge/Ashgate, 2011) and contributions to Museum Making; Making Art History and Reshaping Museum Space (Routledge: 2005, 2007, 2012). Christopher’s research distinctions include two years support from the Australian Research Council, the Paul Mellon Visiting Senior Fellowship (Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts, National Gallery of Art, Washington DC), a Senior Research Fellowship at the Henry Moore Institute, Leeds, a Research Fellowship at the Museo poldi Pezzoli, Milan, and Visiting Senior Lecturing Fellowships at the Hubei Institute of Fine Arts, Wuhan, and the Department of Art and Art History, Duke University, Durham NC.

More Art Herstory posts about Artemisia Gentileschi:

Historic Women Artists in Public Collections: The Kimbell Art Museum, by Olivia Turner

Female Solidarity in Paintings of Judith and her Maidservant by Italian Women Artists, by Sivan Maoz

Plautilla Nelli and the Restoration of her Altarpiece Madonna del Rosario. by Jane Adams

Maddalena Corvina’s Saint Catherine of Alexandria, by Kali Schliewenz

Judith’s Challenge, from Lavinia Fontana to Artemisia Gentileschi, by Alessandra Masu

Artemisia Gentileschi: What Wasn’t in the London Exhibition and Why it Matters, by Jesse Locker

Two of a Kind: Giovanna Garzoni and Artemisia Gentileschi, by Mary D. Garrard

“Artemisia” at the National Gallery: A Review, by Sheila McTighe

The Priceless Legacy of Artemisia Gentileschi: A Curator’s Perspective, by Judith W. Mann

Talking Artemisia Gentileschi with Joy McCullough, Author of “Blood Water Paint”

Art Herstory Resource Page: Artemisia Gentileschi

I am writing a novel featuring the art of Artemisia taking place in Florence? 2023 Target market is woman Fifty plus who know nothing about her’ Has a retrospective of her work ever been organised in Florence since 1991

I believe The one in Casa Buonorotti 2023 did not have many of her works.9