Guest post by Katherine Manthorne, The Graduate Center, CUNY

On this day—May 19th—in 1834 the best-selling female artist and illustrator in post-Civil War United States was born. A native of Salem, Massachusetts, Fidelia Bridges (1834–1923) forged an artistic career that spanned a record fifty years, longer than that of most of her male contemporaries. Under the tutelage of William Trost Richards she first created detailed renderings of small corners of nature in oil on canvas, and later transitioned to watercolor. In his influential book Art in America (1880), critic S.G.W. Benjamin credited her “with developing a charming and original branch of art:” watercolors in which “she composes stalks of grain or wild-flowers in combination with field birds, meadow-larks, linnets, bobolinks, sparrows, or sand-pipers.”

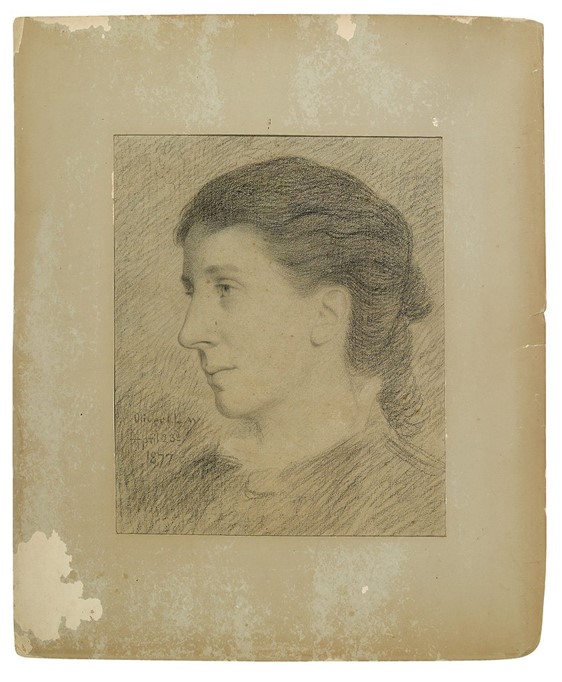

From her debut at the Pennsylvania Academy in 1862, she created about a thousand pictures. Nearing her fiftieth birthday in Spring 1873 she was elected an Associate of the National Academy of Design, joining Eliza Greatorex* as the only female members of that prestigious association. To mark the occasion her friend Oliver Ingraham Lay painted her portrait to be donated to the Academy, and a few years later drew another likeness in pencil (Illus. 1) that reveals her fine features and sensitive expression.

Her artworks of the 1870s seemed to fly off her easel, finding purchasers as fast as she could produce them. She complained, in fact, of feeling “like a machine,” churning out work. A review in The Brooklyn Eagle (July 30, 1874, p.3) confirmed:

Miss Bridges is unquestionably one of the most successful of our local artists….Her pictures appear to have struck the popular fancy, and as a natural result, she has enjoyed a busy as well as a profitable year. Her pictures are of medium size and possess a delightful gray tone, very suggestive of nature. They are simple in subject also, and their story is always interesting. For instance, one of her most popular pictures gave a group of swallows perched upon sprays of wild grass growing in a sandy waste.

One success followed the next, and she was invited to exhibit her work at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876. Soon the Boston-based lithographer Louis Prang took notice of her work, realizing that her subtle use of color and design was perfectly suited to reproduction via his new color printing method. Like Winslow Homer, Thomas Moran, and other well known artists of the day, she accepted his offer to “chromo” her pictures. (Like “google” in our day, “chromo” was so common it came to be used as a verb.)

Her first project for him was an exquisite sequence of twelve pictures of birds and flowers referencing the changing faces of nature over the course of a year. To celebrate her birthday this month, her chromolithograph for May is illustrated (Illus. 2). In it she has delineated a group of birds arranged among flowering branches extending from the left and lower edges of the page. Rendered against a neutral background with little suggestion of formal perspective, her forms appear to lift off the page and come alive, transforming the commonplace into the magical.

Fidelia Bridges continued to exhibit and sell her pictures until 1913, when the Armory Show awakened the American public to the radical new styles of Post-Impressionism, Fauvism and Cubism that made her work appear old-fashioned. But she had weathered many changes, including World War I and the passing of the Nineteenth Amendment granting women the right to vote. Her story holds lessons that resonate today: her determination to establish herself as a professional artist, succeed as a self-supporting and independent woman, and create art works that were popular in her own day and continue to enjoy a robust market today.

*See my Restless Enterprise: The Art & Life of Eliza Pratt Greatorex (U. of California Press, 2020)

A future post will feature episodes from the career of Fidelia Bridges in anticipation of my monograph on her, to be published by Lund Humphries in 2023.

Dr. Katherine Manthorne is Professor of Art History at The Graduate Center, City University of New York. An award-winning art historian, she is the author of monographs on Martha Mitchell, Frederic Church, Louis Mignot, and James Suydam. Her most recent books are Restless Enterprise: The Art & Life of Eliza Pratt Greatorex (U. of California Press, 2020), and Women in the Dark: Female Photographers in the US, 1850–1900 (Schiffer Publishing, 2020). Her latest book, Fidelia Bridges: Nature into Art (Lund Humphries, 2023), shines a light on the accomplishments and contributions of a talented and prolific American artist, at the 100-year anniversary of the artist’s death.

More Art Herstory birthday posts:

The Rich and Complex Character of May Morris, Designer, Embroiderer, Jeweller and Writer, by Thomas Cooper

The Ongoing Revival of Matilda Browne, American Impressionist, by Alexandra Kiely

The Life and Art of Dorothea Tanning: Reflections on her the occasion of her birthday, 25th August, by Victoria Carruthers

Mary Beale (1633–1699) and the Hubris of Transcription, by Helen Draper

Lavinia Fontana: Italy’s First Female Professional Artist, by Liz Lev

The Priceless Legacy of Artemisia Gentileschi, by Judith W. Mann

Other Art Herstory posts you might enjoy:

Women Artists from Savannah at the Telfair Academy Museum, by Julie Allen

Susie M. Barstow: Redefining the Hudson River School, by Nancy Siegel

Marie Spartali Stillman’s The Last Sight of Fiammetta, by Margaretta S. Frederick

Visual Feasts: The Art of Sarah Mapps Douglass, by Erika Piola

Anna Ancher’s Vaccination and Scientific Motherhood, by Alice Price

Celebrating Eliza Pratt Greatorex, an Irish-American Artist, by Katherine Manthorne

The Ongoing Revival of Matilda Browne, American Impressionist, by Alexandra Kiely

Esther Pressoir: Imagining the Modern Woman, by Suzanne Scanlan

Marie Laurencin and the Autonomy of Self-Representation, by Mary Creed

Victorine Meurent, More than a Model, by novelist Drēma Drudge

From a Project on Women Artists: The Calendar and the Cat Lady, by Lisa Kirch