Guest post by Helen Draper, independent scholar and author

This week, in March 1633, clergyman John Cradock DD (d.1652) baptised his baby daughter, Mary Cradock, at the fourteenth-century stone font in the church of All Saints, in the tiny parish of Barrow, Suffolk, some 90 miles from the burgeoning artists’ colony at Covent Garden in London.

Soon, with her father’s encouragement, Mary would develop an abiding preoccupation with the messy, physical act of painting in oil. And so (dear reader) in her twenty-first year to the metropolis she went…

Making the unthinkable appear admirable

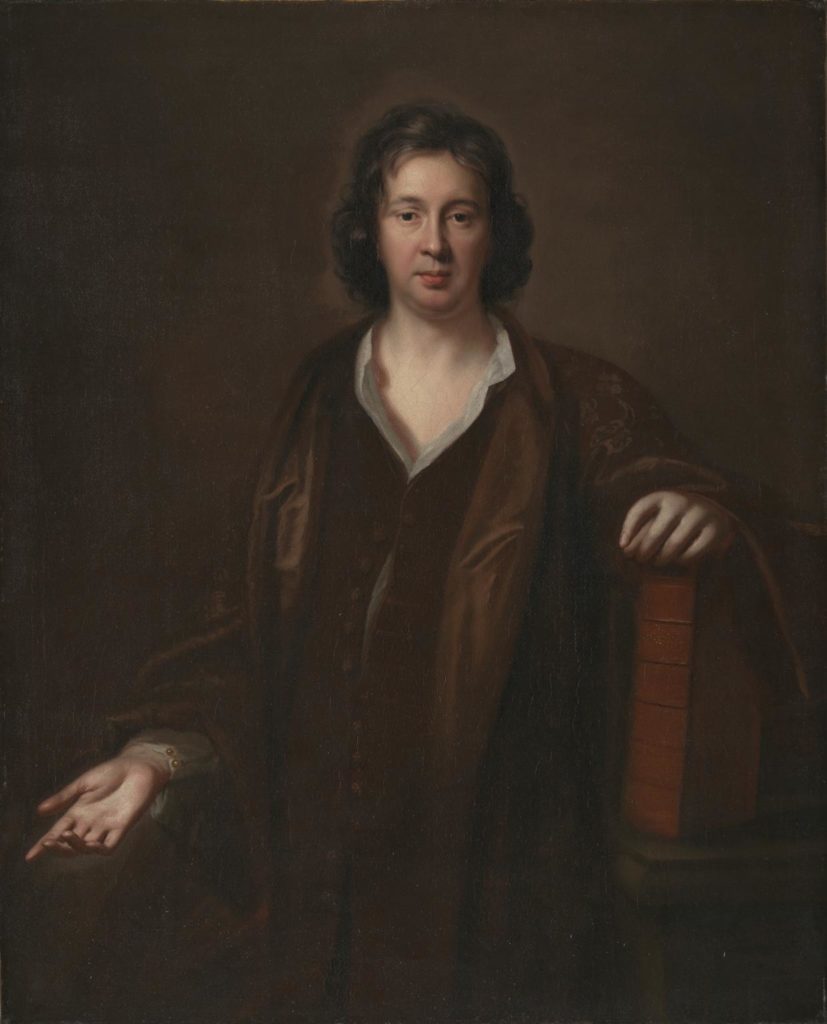

An artist of published repute by 1658, Mary Beale—married and a parent—was not a fully professional portraitist until 1670/1. Thereafter, income from her studio in fashionable, courtly Pall Mall largely supported her family of four. After several years of mundane civil service, husband Charles Beale became her full-time studio manager. He prepared canvases, made and sold pigments and, crucially, kept the accounts. All this when the conventions espoused in early modern rhetoric required a married man to be breadwinner; and discouraged women, married and single, at all levels of society from freely expressing their ideas and creativity.

Shrewd gentlewoman Mary forged a career, nonetheless, by cultivating a “public” identity designed to dispel social disapproval, bestow respectability upon her manual work, and attract a wide and paying clientele. Beale’s reputation relied upon the outward conventionality of her domestic arrangements, and on the collaboration of her spouse and intimate circle. Between these friends and relatives a culture of sociable and material exchange flourished. Gifts of portraits, food, poetry—and influential contacts—became their currency of mutual self-promotion.

A year in the life of the artist

Reader, Mary was a success! But how do we know? In part because Charles Beale kept an annual studio notebook for more than thirty years. In each he listed Mary’s sitters and sittings, completed portraits, the materials she used, the prices paid, debts incurred, the cost of his new suit, and her painterly triumphs, among other things.

Charles’ book for 1677 reveals, for example, that Mary completed 90 portraits on a fully commercial basis that year, depicting 65 different, mainly adult sitters—31 female, 34 male. Most of the women and girls were from the gentry or were titled, while the men and boys were predominantly of the gentry and “middling sort.” This was an incredibly productive and almost certainly exhausting year for Mary. And, thanks to Charles, we can follow it almost day-by-day through a close study of his manuscript record-keeping.

“Discovering” Mary Beale

In recent years Mary Beale’s work has been re-evaluated and re-appreciated, not least of all through the discernment of some private art dealers—Philip Mould, James Innes-Mulraine and Bendor Grosvenor in particular—who, over the past twenty years, have brought to the market many “new” and often (at the time) uncharacteristically informal works.

Tate is also to be commended for accessioning three paintings in recent years, two studies of Mary’s son Bartholomew “Batt” Beale, and one of the scores of portraits she produced of her husband. And just this year another likeness of Batt achieved a record-making £100,000 (c. US $136,894) at auction. Alongside the rediscovery of the full range of her particular oeuvre, the 21st-century resurgence of feminism has also seen a renewed popular interest in historical women artists in general.

My own account of Mary Beale in this blog post is, by nature, perfunctory, the highly-distilled product of more than twenty years study and original research, using the full breadth of manuscript, printed and painted sources known to survive. When I first began to speak and publish on Beale in academic contexts, in 2010, nothing of substance had been written about her since a 1999 exhibition catalogue (Geffrye Museum) by Tate curator Tabitha Barber. Recently, however, accounts of Beale’s life and work seem to pop up everywhere online, and in print. And any coverage is good coverage—right?

Only as good as one’s sources

A strikingly popular category of biography of late is the re-telling of early modern women artists’ lives singly, or in collective form. These accounts are often written by non-specialists who have little or no knowledge of the relevant manuscript sources. They rely instead on digesting, with entirely creditable enthusiasm, secondary or even third-hand, already-published accounts. All accurate, highly-considered research is a wonderful thing and of immense value to the ever-evolving study of women’s contribution to the history of art. Conversely, inaccurate or error-perpetuating accounts are at best unhelpful and, at worst, damaging to its aims.

Far from discouraging anyone from writing about these women and their work, I wish to underline the fundamental importance of basing such narratives on verifiable sources. I, for example, can write from a position of authority on Beale herself and some of the other women who peopled London’s Restoration art world only because I know the sources and her work. As such I am constantly frustrated by the attribution of paintings to Beale which display none of the characteristics of her autograph works but are based on the grounds of tradition or, increasingly, through optimism.

One example of the former is a head and shoulders portrait belonging to St Hilda’s College, Oxford, which has long been called a likeness of “Aphra Behn,” the author and playwright (d.1689), and ascribed to Beale as its painter. As recently as 2020 this inaccurate attribution was repeated in print and, as a result, will probably continue to be made ad infinitum.

Mea culpa…

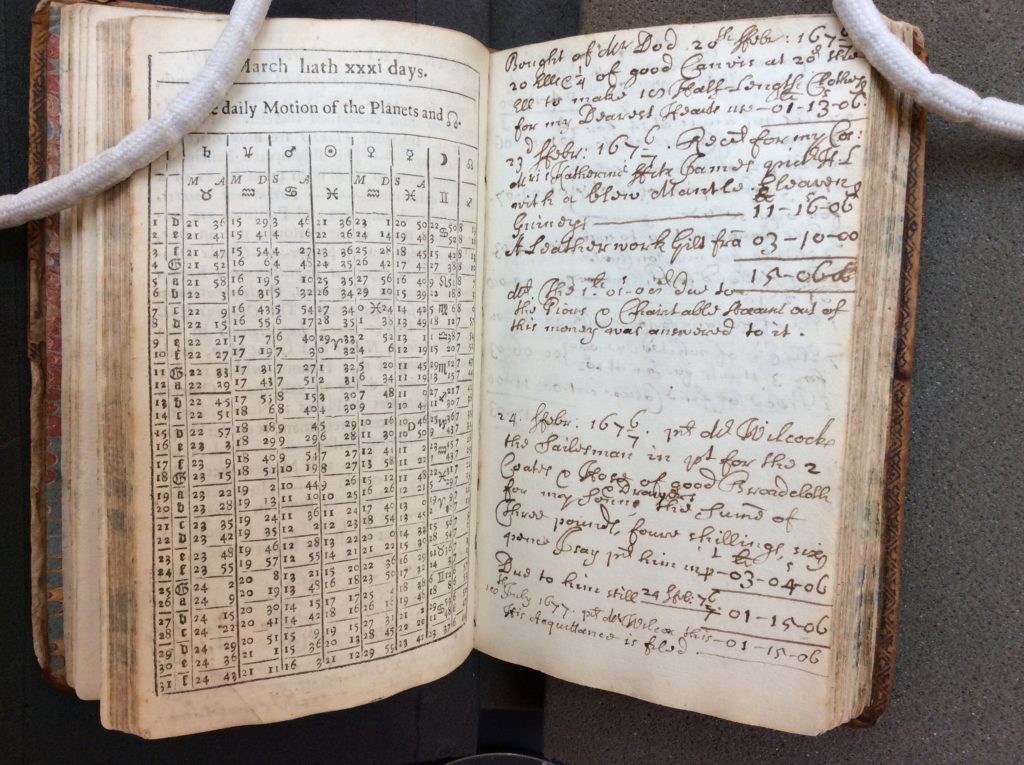

I must here declare that I write from personal, if distant, experience of having perpetuated a similar error, though thankfully not in print. I first transcribed Charles’ 1677 studio notebook in 1999, using one made by an earlier, and truly ground-breaking scholar, Elizabeth Walsh. It was Walsh who discovered the manuscript in the Bodleian Library disguised (as it is) within the blank pages of a printed almanac authored by the astrologer William Lilly (d.1681). Walsh’s transcription of this priceless document—vital not only to Beale studies, but to the history of British art of the seventeenth century—was never published. It, and most of her other research papers were bequeathed to the National Portrait Gallery amongst those of her latter-day collaborator Richard Jeffree (d.1991).

An impecunious independent researcher at the time, I relied entirely upon Walsh’s transcription, and what I could decipher from very poor photocopies of the pages of the ms, in compiling my own. Once I formalised my research as a PhD thesis on Beale, I of course questioned the reliability of second-hand scholarship and referred thereafter directly to the manuscripts themselves. My subsequent character-by-character transcriptions of Charles’ 1677 book and the other surviving volume, from 1680/1 (NPG, Heinz Archive & Library), are supported by high-resolution digital images of each precious page of information.

“The First Rule of Transcription Club is … look!”

In Walsh’s transcription of “1677,” she recorded a passage describing the visit to Beale’s studio of Peter Lely (d.1680), the foremost Restoration portraitist, accompanied by a “Mr Wemburg.” The pair commended Mary’s work and they discussed some plaster casts of limbs which she and Charles had made to draw from. Walsh had been unable to identify “Wemburg”” but speculated, incorrectly, that he became an executor of Lely’s estate. I too tried to trace him but without success. Perhaps unsurprisingly, when I came to transcribe that passage from Charles’ own manuscript, my eye skipped blithely along the relevant line and I too, from sheer laziness and familiarity, recorded the name as “Wemburg.” And so he remained until three days ago.

I was preparing scholarly annotations for that section of my own transcription for future publication and wondered again about the identity of the Beales’ visitor. I selected the digital image of the relevant manuscript folio and took another look at the elusive gentleman’s name … and this time I cracked it! The correct identity of this man, and his activities, are certainly not unknown in literature on the period, but his intriguing presence within the Beale narrative has not thus far been explored.

Reclamation

It came as a shock to confront this small but crucial inaccuracy of my own making. I wondered at my carelessness in replicating the mistake, and the insight I had denied myself by not interrogating the secondary text on which I had at first relied. After all, accuracy is everything if we are to attain a real understanding of the lives, works and achievements of historical women artists, especially when inaccuracy only serves to undermine even the most justified and well-argued piece of art-historical “reclamation.”

And as for the ex-Mr Wemburg (dear reader), my forthcoming book will tell all…

Dr. Helen Draper completed her interdisciplinary PhD thesis “Mary Beale (1633–1699) and her ‘paynting roome’ in Restoration London” (Institute of Historical Research & Courtauld Institute) in 2020, and is currently writing the first art-historical monograph on Beale and her studio [forthcoming in the series Illuminating Women Artists, from Lund Humphries]. A previous publication, “’Her painting of apricots’: the invisibility of Mary Beale (1633–1699)” (2012) presented a ground-breaking first transcription of the artist’s own instructions on how to paint in oils. Helen’s MA in Paintings Conservation, and many years of professional experience in examining and caring for works of art, bring an extra dimension of technical understanding to her writing on Beale, and on the materials and business of seventeenth-century portraiture.

Other Art Herstory blog posts you might enjoy:

Finding Catherine Read, by Adam Busciakiewicz

The Lost Works of Susanna Horenbout, Female Artist at the Tudor Court, by Sylvia Barbara Soberton

Susannah Penelope Rosse: Painting for Pleasure in Seventeenth-Century England, by Anna Pratley

A Room of Their Own: Now You See Us Exhibition at Tate Britain, by Kathryn Waters

Portrayals of Mary Magdalene by Early Modern Women Artists, by Diane Apostolos-Cappadona

Angelica Kauffman: Grace and Strength, by Anita Viola Sganzerla

“Black-works, white-works, colours all”: Finding Susanna Perwich in her Seventeenth-Century Embroidered Cabinet, by Isabella Rosner

Levina Teerlinc, Illuminator at the Tudor Court, by Louisa Woodville

Susanna Horenbout, Courtier and Artist, by Dr. Kathleen E. Kennedy

Angelica Kauffman and Mary Moser: Founding Women Artists of the Royal Academy

“Bright Souls”: A London Exhibition Celebrating Mary Beale, Joan Carlile, and Anne Killigrew, by Dr. Laura Gowing

A wonderfully thoughtful and enlightening essay. Many thanks to the author for sharing her work with us!