Thoughts on Maestras at Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza

Guest post by Jitske Jasperse, Instituto de Historia, CCHS, Madrid

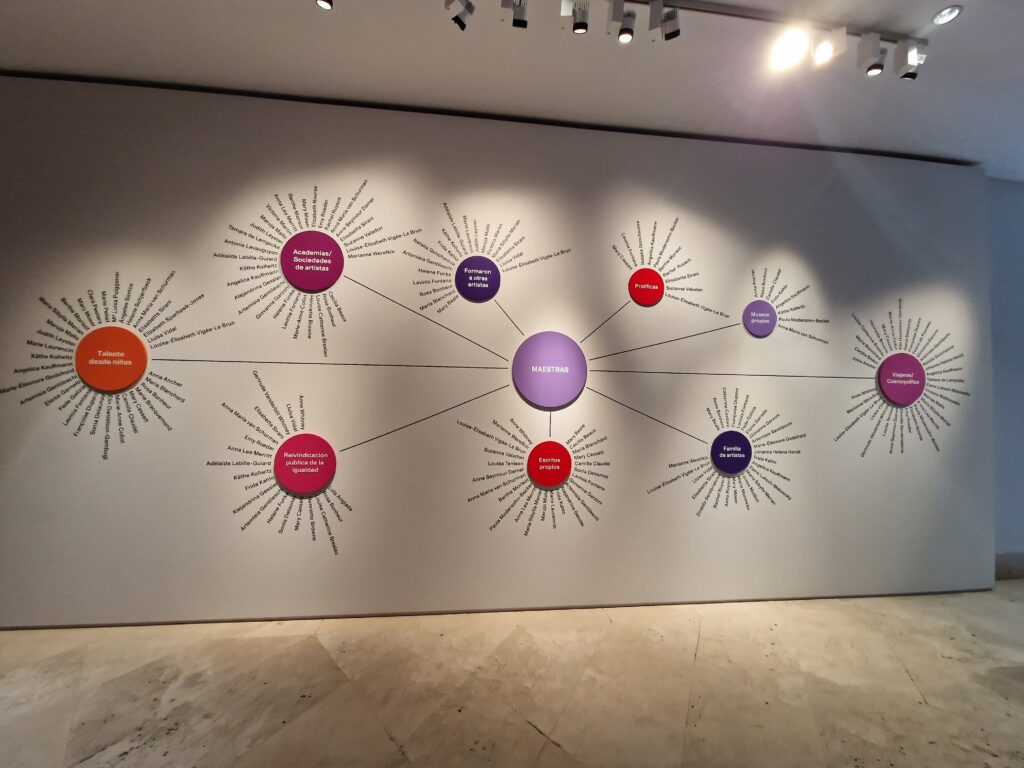

With Maestras, or Women Masters, curator Rocío de la Villa created an ambitious exhibition for Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid (on show until 4 February 2024). It is not just the first show in Spain dedicated to women artists from the late 1500s to the early 1900s. It also offers an impressive presentation of the diverse media in which these women worked (e.g., paint on canvas, bronze, stone, textile, pencil, watercolor). Moreover, Maestras provides the chance to get acquainted with women artists who did not (yet) make it into the art historical handbooks, or whose names may appear less frequently in the media (fig. 1).

Sisterhood

In eight sections, women—as artists and subjects—take on different roles, but the running thread is sisterhood, of which some examples are discussed in this review. Although presented in the exhibition as a modern notion, the Oxford English Dictionary states that the earliest English evidence for the word is found in the writing of John Gower. In his Confessio Amantis (The Lover’s Confession, 1390) he speaks of sisterhood when Medea—wife of Jason—sends a golden mantle to Jason’s new wife Creusa. Creusa dies after trying on the mantle, indicating that the sisterhood she shared with Medea is a false one; interestingly, antagonism and rivalry between women are not explored in Maestras.

The medieval period, however, also saw many sisterhoods that were amicable, especially in religious context—from cloistered nuns to Beguines. This is the kind we also encounter in Maestras, for example Henriette Browne’s Sisters of Mercy (1859) (fig. 2). This is one of a number of her paintings in which nuns take center stage. In 1864, The Fine Arts Quarterly Review (p. 232), remarked that “the public, who feel more than they judge, are carried away by the pictures of Madame Browne, precisely because they find in them that shade of perfect good taste and exquisite sentiment which belongs to no one so much as to the true lady.“ Here we find the societal (and patriarchal) sentiments of the time: a woman should always be a lady.

Sisters in Arms

Maestras’ accompanying brochure, of which the texts can also be found on the museum’s website, presents Artemisia Gentileschi, Fede Galizia, and Lavinia Fontana as sisters in arms who “drew attention to the silence and exclusion imposed by patriarchal discourse.” All three painted the moment in which Judith presents to the viewer the head of Holofernes. Perhaps Gentileschi’s heroine is the most intriguing in that Judith nor her maid is facing the viewer (fig. 3).

With their heads turned away to something beyond our view, we follow them and their gaze, ignoring the head of Holofernes. While this composition is based on a painting with the same theme made by her father Orazio, Gentileschi made different choices in color, detail, and the cropping of the background. These make her figures appear more powerful than his.

Yet without a more careful analysis of iconography and composition, or the inclusion of comparative material painted or written by men, it is hard to understand how exactly these women artists dealt with patriarchy. That patriarchy was indeed an obstacle, was voiced by Gentileschi who complained that her male colleagues were paid better. Sisterhood is more explicitly embodied in the paintings themselves: Judith who beheaded Holofernes, Jael who drove a pin through Jael’s ear, and Portia who wounded herself to show she could be trusted. These sisters in arms showed strength.

This also can be said of Judith Leyster’s small and delicate painting of a young woman who is dedicated to her needlework by candlelight (fig. 4). She must feel the man’s hand on her shoulder while he offers her money in exchange for her love, but she ignores him.

Flower Power

The rooms devoted to botany and the Enlightenment testify to the cosmopolitan world women artists were part of. Women like Maria Sibylla Merian (1647–1717) and her daughter Johanna Helena Herolt (1668–1723)—who both travelled to Suriname—created botanic aquarelles, or drawings in transparent watercolors, for Agnes Block (1629–1704) (fig. 5). Block was a wealthy mercantile’s wife who owned a country estate with botanical garden, for which she acquired the plant seeds via exchanges with Dutch and international botanists. Aided by scientific research, visits to the botanical gardens of their patrons, and artistic representations that served as models, women artists explored the natural life and captured it with a tremendous eye for detail.

From this we may get the impression that the depiction of the natural world—often in idealized ways—was foremost a woman’s job. Yet we know that men also made botanical illustrations and painted still lifes. In fact, Maria Moninckx (1673–1757) collaborated closely with her father, creating the the nine-volume Moninckx Atlas, depicting 420 plants from the Hortus Medicus of Amsterdam. Do we do justice to women’s art if we do not explicitly include men? After all, they were patrons, colleagues, collaborators, opponents, and even oppressors.

Sisterhood: Harmony

Sisterhood is explored in more depth through the intimate representations of nuns, lovers, siblings, and friends. Sometimes we can only guess how the women are connected: What is said and not said and done between the two women Berthe Morisot (1841–1895) painted? The portrait with the title The Sisters shows two elegantly and identically dressed women (fig. 6).

At first sight they seem to be sharing the sofa, but a closer look reveals that the woman on the right is sitting on a chair. They are connected not through their gaze, but via their matching outfits, hairstyle, jewelry, and the hands that are almost touching behind the fan. Yet we can only guess if they are siblings, close friends, or lovers.

The absence of men in the paintings presented in this room is striking. In the past men were likely to have been active as viewers (and critics), not unlike the present museum’s visitors. Yet to the women painters their existence seems not to have mattered. They were creating a room of one’s own. Marie Laurencin (1883–1956) did so in a painting representing two young women and a dog in soft colors (fig. 7).

Looking at the viewer, the girl in the front plays a guitar, while the dog throws back his head and howls along, observed by the girl sitting behind him. The girls’ gazes and our own are magnified by the unique frame, made from mirrors and glass beads. Through it fragments of ourselves and of the other artworks mirrored in the frame become part of the intimate scene.

Spanish Sisters

Maestras’ close observers will also discover numerous women artists from Spain. Madama Anselma, splendidly painted in 1865 by Henriette Browne, was a pseudonym for the Spanish painter Alejandrina Gessler (1831–1907). She was trained in Paris together with Mary Cassatt, who visited Spain in Seville in 1872–1873. Gessler was one of the first women to be accepted into Madrid’s Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando. Maruja Mallo (La verbena, 1927) and Ángeles Santos Torroella (Anite y las muñecas, 1929) take us to their more surrealist and magical worlds, painted in the early twentienth century. These world are not only inhabited by women, but also by men, children, dolls, and animals (fig. 8).

Displayed in majestic purple rooms, Maestras paints a vibrant picture of the variety of media, genres, forms, and sizes in which women artists from the sixteenth to early-twentieth centuries worked. Making use of connections, opportunities, and lived experiences, the women whose work is presented at the Thyssen-Bornemisza share with us their talent, professionalism, interests, and in/dependence.

Women Masters is on at Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza through February 4, 2024. A smaller version of the show will travel next year to the Arp Museum in Remagen, Germany.

Dr. Jitske Jasperse is an art historian specialized in medieval art and women. Her recent publications include Medieval Women, Material Culture, and Power: Matilda Plantagenet and Her Sisters (2020) and Het vrouwelijk oog wil ook wat: vrouwen als opdrachtgevers, verzamelaars en kunstenaars (2021). She is the series editor for CARMEN Visual and Material Cultures.

Other recent exhibition reviews on the Art Herstory blog:

Rachel Ruysch at Munich’s Alte Pinakothek, by Erika Gaffney

Roma Pittrice: Women Artists at Work in Rome Between the Sixteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, by Alessandra Masu

Female Artists and their Remarkable Careers: An Appeal to Rethink Art History, by Jenny Körber

Making Her Mark Leaves its Mark at the Art Gallery of Ontario, by Isabelle Hawkins

Early Modern European Women Artists at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, by Erika Gaffney

Making Her Mark, An Essential Corrective in the History of Art, by Chadd Scott

Carlotta Gargalli 1788–1840: “The Elisabetta Sirani of the Day,” by Alessandra Masu

Reflections on Making Her Mark at the Baltimore Museum of Art, by Erika Gaffney

Marie Laurencin: Sapphic Paris, A Review, by Alice M. Rudy Price

Material Re-Enchantments: A Review of Remedios Varo: Science Fictions, by Suzanne Karr Schmidt

Thoughts on Feminist Art History in the Wake of Artemisia: Vrouw & Macht at Rijksmuseum Twenthe, by Jitske Jasperse

The Many Faces of Suzanne Valadon, by Suzanne Singletary

Sofonisba Anguissola in Holland, an Exhibition Review, by Erika Gaffney with Cara Verona Viglucci

Thérèse Schwartze (1851–1918), by Ien G.M. van der Pol

Anna Dorothea Therbusch: A Woman Painting Against Eighteenth-century Odds, by Stephanie Pearson

Rosa Bonheur—Practice Makes Perfect, by Ien G.M. van der Pol