Guest post by Alessia Motti, Art History student, La Sapienza University of Rome

Suor Plautilla Nelli (1524–1588) was a nun-artist in the convent of Santa Caterina in Cafaggio. She is one of the few female artists mentioned in Vasari’s The Lives of the Artists. She is the first Florentine woman artist for whom we have documents that record her artistic production. Plautilla Nelli contributed, along with her sisters, to the spread of Savonarola’s spirituality throughout the Italian peninsula. And, as stated by the famous author of the Lives, her paintings were in “the homes of Florentine gentlemen.” Though she was nearly forgotten by history, experts are now rediscovering her story and restoring her artworks.

The Spiritual Legacy of Savonarola: The Convent of Santa Caterina da Siena

Studying the artistic production of female monasteries allows us to delve into an important aspect of the community that governed and sustained them. For example, we can assess the heights to which nuns’ artistic production could attain. It is also important to understand how they used art to consolidate relationships with merchants and wealthy families.

Santa Caterina da Siena, also called Santa Caterina in Cafaggio, is noteworthy among Florentine convents. Camilla Bartolini Rucellai (1465–1520) founded it on September 30, 1500. She took vows under the name Sister Lucia, becoming a Dominican tertiary and a follower of Girolamo Savonarola (1452–1498). Thus, the monastery could be considered one of the key centers for spreading the friar’s theories through artistic production. It expanded to accommodate 133 nuns by 1562.

In this convent, at the age of 14, in 1538, Pulisena Margherita Nelli took the veil under the name Plautilla. The year before, her sister, Costanza Pulisena Romola, took vows in the same convent under the name Sister Petronilla. Plautilla became abbess three times: from September 1563 to September 1565, from 1571 to 1575, and finally from 1583 to 1585. She was known as the “first female painter of Florence.” But Vasari indicates that the first female painter in the city was Antonia (1456–1491), daughter of Paolo Uccello.

Plautilla Nelli: Between Painting and Religion

Vasari mentioned Plautilla Neli in his Life of Properzia de’ Rossi (1490–1530). He stated that she diligently imitated the works of “excellent” masters. To the famous biographer, Suor Plautilla appeared as a “venerable and virtuous” artist. She was heir to the artistic tradition of the “School of San Marco.” In that role she received a legacy of drawings, cartoons, sketches, and models that belonged to Fra’ Bartolomeo. Fra’ Paolino inherited Fra’ Bartolomeo’s works previously, and used them until his death in 1547. For a long time, critics identified Fra’ Paolino as Plautilla’s master.

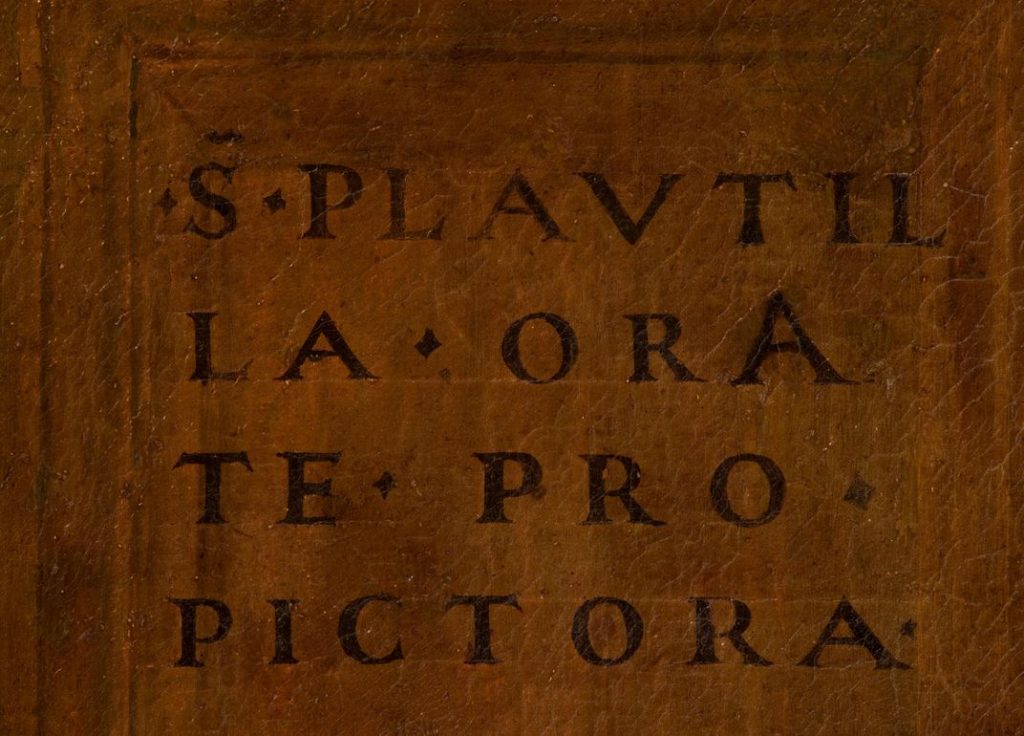

Her style is simple and solemn, infused with strong Christian spirituality. The affirmation of her role as a painter also emerges through the way she signed her works. For example, she uses the imperfect tense of the Latin verb “faciebat” in the Pentecost (fig. 1) to sign the altarpiece of the Church of San Domenico in Perugia. Similarly, she adopted the expression alongside her signature, “Orate pro pictora,” “pray for the painter,” (fig. 2) in the Last Supper, created for the refectory of the convent.

Artists of San Marco, including Fra’ Bartolomeo’s Pala Cambi (1509), usually used this phrase in the masculine form. The colophon of a book about Savonarola’s life also bears witness to Nelli’s awareness of her artistic talent. In this book that belonged to her sister, next to her signature, Plautilla identifies herself as “dipintora,” “painter.”

Plautilla Nelli’s workshop

Sister Plautilla Nelli was the head of a flourishing workshop of nun-artists. Among her religious sisters were Suor Prudenza Cambi, Suor Agata Traballesi, Suor Maria Ruggieri, Suor Veronica Niccolini, Suor Dionisia Niccolini, Suor Maria Angelica Razzi, and Suor Alessandra Milanese.

Suor Prudenza Cambi

Sister Prudenza Cambi, born Fiammetta, came from a noble family residing in the San Giovanni district. The region was home to many “piagnoni” (Savonarola’s followers). Her grandfather Francesco was one of the signatories of the petition in favor of Savonarola in 1497. Fiammetta took vows in 1544, when her great-aunt, Sister Filippa, was abbess. Cambi oversaw the artistic activities of her sisters while Nelli was abbess. A document regarding the sale of one of her works in the 1560s indicates that she was a successful painter. However, no works by her have survived.

Suor Agata Traballesi and Suor Maria Ruggieri

The lives of Suor Agata Traballesi and Suor Maria Ruggieri are still shrouded in mystery. But we know that they were artists. Serafino Razzi, Suor Maria’s brother who wrote about the nuns in Nelli’s monastery, briefly mentions their work. The former, whose name was likely Camilla, came from an artistic family and took vows in 1573. The latter, born Margherita or Maddalena, was the daughter of a physician from Arezzo. She entered the convent in 1572 and became “mother-painter” in the early seventeenth century. Razzi reports that Suor Agata worked on canvas and wood, and specialized in manuscript miniatures. However, no works by either have been identified. The image below (fig. 3) by Plautilla Nelli may be representative of the miniatures produced by her workshop.

Suor Veronica and Suor Dionisia Niccolini

Suor Veronica, born Laura, and Suor Dionisia (Dianora) Niccolini came from an aristocratic family. Their relatives held important political roles in the city. They entered the convent in 1546 and 1550. According to Rucellai, who also wrote about the monastery, the two sisters chose this convent because of the fame Suor Lucia. Their decision to enter Santa Caterina signals the great prestige it had among the élite. Dionisia was the only woman included in Paolo Mini’s list of famous Florentine sculptors in Discorso sulla nobiltà di Firenze (1593). She was known for her devotional terracotta images. Her sister specialized in producing paintings on paper and canvas that simulated tapestries. The sale of her art contributed significantly to the convent’s income.

Suor Maria Razzi

Maria Razzi entered Santa Caterina in 1552 with the name Maria Angelica. Her brother Girolamo, a well-known playwright, provided her dowry. After about ten years, she became a noted sculptor. She was probably responsible for creating the sculptures of the Nativity for the Dominican monastery of San Giorgio in Lucca in the 1580s. Her brother Serafino wrote that she created terracotta statues of the Madonna, saints, and angels. He mentioned specifically two sculptures she made of the Madonna with the sleeping Christ Child. She made one for the Church of San Domenico in Perugia and the other for the sacristy of San Marco in Florence.

Rosary to Saint Dominic, 1560–1580. Florence, Museo di

San Marco.

Suor Alessandra Milanese

Alessandra Milanese came from an aristocratic family and took vows in 1581, without changing her name. She likely chose the convent due to the presence of a relative, Suor Laura di Carlo Martelli. Convent documents mention that she painted a small Madonna donated by Prudenza Cambi to Filippo Taddei in 1589.

Artistic Activity

These eight nun-artists constitute a small portion of the sisters and novices who contributed to Santa Caterina’s artistic production. It is difficult to identify the artistic contributions of others because most of them did not sign their works. Also, many documents have been lost that might have helped with the effort. However, their skill contributed to the fame of the convent itself. As Razzi wrote, they were engaged “with praise and benefit to their house, in painting pictures on canvas and wood.”

Many large-scale projects were the result of collective efforts, with multiple sisters working under the direct supervision of Suor Plautilla. A document related to an altarpiece for the convent’s dormitory reveals that it was painted “by the hand of our Mother Sister Plautilla and her companions.” However, we cannot rule out that Plautilla Nelli herself designed some works, which her workshop painted.

Santa Caterina de’ Ricci

Plautilla Nelli created the iconography of Santa Caterina de’ Ricci (1522–1589). The saint entered the Dominican convent of San Vincenzo in Prato and was a fervent supporter of Savonarola. Recalling the simplicity of Fra’ Bartolomeo’s painting, Plautilla painted portraits of the saint in profile against a plain background. Her depictions are reminiscent of the images of the Ferrara preacher, particularly the two portraits realized by the friar-artist in the early sixteenth century (fig. 5, 6).

Marco. Figure 6 (right): Fra’ Bartolomeo, Portrait of Savonarola as San Peter Martyr, c. 1508. Florence,

Museo di San Marco.

The four paintings (figs. 7, 8, 9 and 10), executed by Plautilla and her workshop, depict the same Dominican in profile, sharing a common design. They are located in Florence, Siena, Perugia, and Assisi. The works in Siena and Perugia (figs. 7 and 8), painted on canvas by Plautilla and slightly larger than the others on wood, are of superior artistic quality compared to those in Florence and Assisi (figs. 9 and 10).

di San Domenico. Figure 8 (right): Plautilla Nelli, Santa Caterina da Siena/de’ Ricci, c. 1560–1580. Perugia, Galleria

Nazionale dell’Umbria.

Florence, Museo del Cenacolo di Andrea del Sarto. Figure 10 (right): Plautilla Nelli, Santa Caterina da Siena/de’ Ricci, c. 1560–1580. Siena, Convento di San Domenico.

These quality differences are due to the collaboration of her sisters in the convent’s artistic production.

Reflectographic investigations reveal that the profiles in the Santa Caterina series coincide with her profiles in Fra’ Bartolomeo’s Cambi Altarpiece. Plautilla Nelli and her sisters likely used the same design, derived from the altarpiece by the friar-artist of San Marco, to create multiple works. These include the Madonna and pious women in the Lamentation (see feature image, above); and the two lunettes depicting Santa Caterina Receiving the Stigmata (fig. 13) and the Delivery of the Rosary to Saint Dominic (fig. 4). Nelli and her workshop also painted a lunette representing a Crucifixion (fig. 11).

The Last Supper

The Last Supper (fig. 12) is a 7-meter-long and 2-meter-high painting with life-size characters. The hands of different artists with varying levels of experience are evident, especially in the heads of the Apostles. On the table covered with a linen cloth, Chinese porcelain is portrayed with great technical skill, suggesting direct study of these precious objects. Though expensive, porcelain was not difficult to obtain since many sisters came from merchant or noble families.

The painting’s horizontal format is in line with the taste of the élite class in Florence at the time. Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper (pre-1498), which circulated through prints and painted copies, was probably the model for this oil-on-canvas painting. Both works are set in refectories and have similarities in the hands of the Apostles. And both paintings place Christ at the center of a long rectangular table. Both use the profil perdu (a technique used in portraiture that involves the partial or complete obscuring of the profile) for the figure of Judas.

Fame

In 1587, the nuns of the Florentine monastery of San Domenico al Maglio turned to the convent of Santa Caterina da Siena for the execution of a Madonna painting. They paid more for it than they had paid the artist Antonio Stiattoni for a similar work. This marked the beginning of a fruitful collaboration between the two convents. The partnership resulted in several artworks created between 1594 and 1597. But it also generated an ongoing exchanges of ideas and reflections on art.

The convent of Santa Caterina is significant for the quality it achieved and for the tangible and archival testimonies we have. The lunette of Santa Caterina Receiving the Stigmata (fig. 13), by Plautilla Nelli and her workshop, indicates that the nuns felt the influence of Northern European art. In 1602, Razzi wrote that their works adorned homes and monasteries throughout the peninsula. Modesto Biliotti, a friar from the convent of Santa Maria Novella, confirmed this statement.

Conclusions

Nelli’s technical-pictorial skill and expertise also emerge through her copies of works by artists such as Bronzino and Fra’ Bartolomeo. In this way she demonstrates that she measured herself against the great masters. The high cost of her works that the payment documents mention, which patrons eagerly purchased, affirm her status as a “pictora.” In the late Cinquecento, Francesco Pitti wrote to his relative Francesca Billi, a nun in the convent of Santa Caterina, that the quality of the angel heads he requested was high. On this basis, he would have paid any amount of money the nuns asked.

Shortly after her death, Biliotti wrote an obituary in which he praised Nelli not for her role as abbess but for her artistic talents. Afterward, the workshop continued to excel, combining artistic technique with a strong religious commitment. Rucellai’s chronicle provides further confirmation of Nelli’s celebrity and the important role of her workshop. In her narrative, Rucellai describes Sister Plautilla Nelli as an “excellent oil painter, highly esteemed, and marvelous in miniatures.”

This accolade confirms Vasari’s comment at the beginning of Properzia de’ Rossi’s Life. He wrote, “It is a remarkable fact, that whenever women have at any time devoted themselves to the study of any art or the exercise of any talent, they have for the most part acquitted themselves well, and have even acquired fame, a circumstance of which innumerable examples might easily be adduced.”

Author biography

Alessia Motti graduated from the Università degli Studi di Firenze with the highest mark, cum laude. She is currently continuing her studies in Art History at La Sapienza University of Rome. Alessia’s academic interests focus on modern art history, museology, and the early modern female artists in convents. She is also engaged with postcolonial studies, examining the intersections between art, history, and cultural narratives. She curates an Instagram art account: @divulgazioneartistica.

More Art Herstory blog posts about artist-nuns:

Plautilla Nelli and the Restoration of her Altarpiece Madonna del Rosario, by Jane Adams

Sister Eufrasia Burlamacchi (Lucca, 1478–1548), by Loretta Vandi

Orsola Maddalena Caccia (1596–1676), Convent Artist, by Angela Ghirardi

Sister Caterina Vigri (St. Catherine of Bologna) and “Drawing for Devotion,” by Kathleen G. Arthur

More Art Herstory blog posts about Italian women artists:

Three Historic Women Artists Exhibitions: A Dispatch from Italy, by Alessandra Masu

Roma Pittrice: Women Artists at Work in Rome Between the Sixteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, by Alessandra Masu

Female Solidarity in Paintings of Judith and her Maidservant by Italian Women Artists, by Sivan Maoz

Maddalena Corvina’s Saint Catherine of Alexandria, by Kali Schliewenz

Exhibiting Artemisia Gentileschi; From the Connoisseur’s Collection to the Global Museum Blockbuster, by Christopher R. Marshall

Portrayals of Mary Magdalene by Early Modern Women Artists, by Diane Apostolos-Cappadona

Judith’s Challenge, from Lavinia Fontana to Artemisia Gentileschi, by Alessandra Masu

Stitching for Virtue: Lavinia Fontana, Elisabetta Sirani, and Textiles in Early Modern Bologna, by Patricia Rocco