by Erika Gaffney, Art Herstory Founder

The world has waited a very long time—300 years, give or take—for the first monographic exhibition of the Amsterdam-based flower painter Rachel Ruysch (1664–1750). The first iteration of Rachel Ruysch: Nature into Art is on now, in Munich. The Toledo Museum of Art will host a version of the show this spring. It then moves to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston in the late summer.

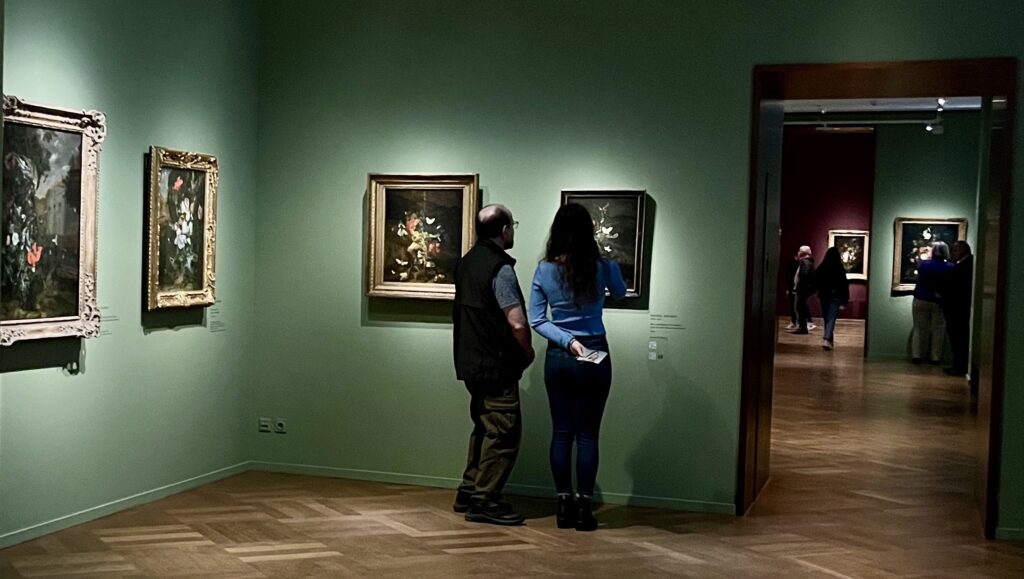

To cut to the chase, the installation at Munich’s Alte Pinakothek is a triumph. It pays fitting tribute to “the Amsterdam Pallas,” as her contemporary Jan van Gool described her. The show includes a generous number of paintings from across Rachel Ruysch’s career. This is no mean feat, since her active painting period spanned seven decades.

The display also includes paintings and drawings by artists who influenced Ruysch, and those whom she influenced. The curators have assembled a truly impressive number of artworks and contextual materials. In all there are some 80 paintings from public and private collections in 14 countries, including 57 paintings by Rachel Ruysch herself. The show also includes 41 works on paper; almost 600 zoological and botanical specimens; and historical optical instruments.

There’s more to say about the concepts behind Rachel Ruysch: Nature into Art—including its interdisciplinarity—and about the specifics of this initial version of the show. Interestingly, it is the Alte Pinakothek’s first exhibit, ever, with a woman artist as its central focus.

But first: isn’t it remarkable that an artist as prolific, and as acclaimed in her time, as Ruysch has not inspired a solo exhibition before now? This state of affairs is worth interrogating.

Hardly a Wallflower

Rachel Ruysch was one of the most celebrated artists in Europe from the late seventeenth- to the mid-eighteenth century. Connoisseurs were eager to own works by her, and willingly paid high prices for them. According to the Ruysch webpage on the National Gallery (London) site, her paintings “often sold for more in her lifetime than Rembrandt’s did in his.”

At the age of 29, already a successful artist, Ruysch married, apparently for love. Her husband, Jurien Pool, was also a painter. She continued to pursue her painting career throughout her marriage, signing her work with her maiden name. She was the first female member of The Hague painters’ society Pictura. And Ruysch was a court painter to the powerful Duke Johann Wilhelm II in Düsseldorf. Upon her death, contemporaries compiled and disseminated a collection of poems in her honor.

Clearly, Rachel Ruysch was an extraordinary woman and artist, not merely recognized in her time, but famous. The exhibition catalog notes that there are at least 150 Ruysch paintings still in existence. So her body of extant work is not small. And her oeuvre is far from hidden; some of her paintings are in private hands, but many are held in museums throughout the US and Europe. Yet never before—not during her lifetime, not in the nearly three centuries since—has there been a solo exhibition of her work.

Why Now?

So how did 2024–2025 become the right moment for Rachel Ruysch: Nature into Art?

According to the exhibition catalog, Robert Schindler conceived the project initially. Schindler is William Hutton Curator of European Art at the Toledo Museum of Art.

Schindler took inspiration from a signed and dated Anna Ruysch painting that the David Koetser Gallery displayed at a 2017 art fair. Prior to viewing this work, Schindler hadn’t realized that Rachel Ruysch had a sister who was a talented painter. He was intrigued by Rachel’s and Anna’s different career paths.

It struck him, too, that despite her fame in her lifetime and her inarguable success as an artist, there was so little published research on Rachel Ruysch. So, with the support of a Clark Art Institute Curatorial Fellowship, Schindler conducted research on the Ruysch sisters. He developed the idea of an exhibition with Rachel as its central focus. Schindler envisioned that the show could bring together paintings by the two sisters, and explore the scientific environment that infused their work.

Schindler’s vision appealed to colleagues at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston—home of the Center for Netherlandish Art, and of two Rachel Ruysch paintings—and at Alte Pinakothek, which owns four paintings by Rachel Ruysch. Thus the project evolved into a joint, international endeavor.

Fruitful Ground

The seed that was Schindler’s idea landed on fertile ground. In part this may be because aspects of Ruysch’s life and work resonate with themes of cultural interest today. In Rachel Ruysch: Nature into Art, botanists, zoologists, and historians of science contribute to the contextualization of Ruysch’s work, ensuring an interdisciplinary presentation. The show explores issues to do with (at least): colonization, especially as it impacted studies of botany and zoology; plant humanities, including the role of art in the study of natural history; and the history of science, including the optical revolution.

It is possible that Ruysch’s posthumous fortunes in the twenty-first century have helped to ensure positive reception of an exhibit such as this. In 2019, CODART selected Rachel Ruysch’s painting Floral Still Life, held at the Toledo Museum of Art, as one of 100 Dutch and Flemish artworks in the first CODART Canon. (CODART is an international network of curators of Dutch and Flemish art. The Canon is its “top 100” list of historically important works of art before 1750. The list includes only four other works by women.)

Over the last few years, paintings by Rachel and her sister Anna have generated considerable interest—and high sale prices—at auction. Rachel Ruysch’s inclusion in recent exhibitions to do with women artists has familiarized twenty-first-century art lovers with her name. (For a list of these shows, see the “current and past exhibitions” section of the Art Herstory Rachel Ruysch resource page.) And, though this eventuality was not necessarily foreseeable when the exhibition was first conceived, several high-profile public collections have acquired Rachel Ruysch paintings.

The Ruysch Sisters at Auction in the Twenty-first Century

These examples illustrate the passion of collectors—whether public or private—these days for art by Rachel Ruysch and her younger sister Anna, whose oeuvre is estimated at about 20 extant paintings:

- In December 2022, results for two paintings by Anna Ruysch smashed the estimates:

- Still life of flowers, with peonies, carnations, variegated tulips… sold for £327,600, more than four times the high end of the estimate range of £50,000–70,000.

- Still life of fruit, with peaches & grapes … went for £201,600; the estimate was £30,000–50,000.

- In January 2022, Still life of carnations, hibiscus, morning glories, and other flowers on a ledge, with a butterfly, by Rachel Ruysch, sold for US $365,400; the estimate was $80,000–120,000.

- In May 2021, Still life of flowers, with butterflies, insects, a lizard and toads… generated a sale price of £340,200, far exceeding the high estimate of £120,000.

Recent Rachel Ruysch Acquisitions by Museums

In 2023 alone, three museums acquired Ruysch paintings, all of which are on view now in Munich:

- The National Gallery of Ireland purchased Ruysch’s Vase of Flowers with an Ear of Corn, the first work by a woman artist to join the Gallery’s Dutch collection. The artist signed it with her name, the year, and also her age (79!) at the time of completion.

- The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston added Ruysch’s A Still Life of Flowers in a Glass Vase on a Marble Table before a Niche to its collection.

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art acquired Rachel Ruysch (1664–1750), a rare collaborative portrait. Michiel van Musscher depicts the artist at work on a floral painting, which element is contributed to the portrait by Ruysch herself.

The Exhibition

Rachel Ruysch: Nature into Art begins in space that has the feel of a dark, segmented corridor, but it quickly opens out into wider, brighter space. Its five sections shed light on particular facets of Ruysch’s artistic career. In early December, about a week after the show opened, the galleries were populated but not crowded. Happily, it was possible to view the paintings at very close range. And visitors could photograph (without flash) many of the paintings—but not all of them, due to conditions that lending institutions imposed.

“An Auspicious Beginning”

The segment labeled “An Auspicious Beginning” highlights Rachel Ruysch’s early career, juxtaposing her work with that of contemporaries such as Willem van Aelst, with whom she trained, and Maria van Oosterwijck (also spelled Oosterwyck). This gallery prominently features the collaborative portrait depicted above.

The Two Sisters

This section juxtaposes four paintings by Anna—two from museums, two from private collections—with select paintings by Rachel. Their work is presented together for the first time in public, revealing similarities and differences in their artistic practices.

Art, Nature, and Science

This section delves into the intersection of art and scientific discovery, and the era’s burgeoning interest in botany and zoology. Two features of this gallery are particularly worth noting. The first is that the Munich presentation is site-specific. The reason is that the specimens presented in this room fall into the category of hazardous materials. The organizers had to make special transportation arrangements even to convey them across Munich from the botanical and zoological state collections. By the same token, the “science” portions of the Toledo and Boston versions also promise to be unique.

And here’s the second feature to note: it is here that visitors see the greatest concentration of works by women other than Ruysch. This sector boasts botanical and zoological illustrations by Johanna Herolt, Alida Withoos, and Cornelia de Rijck (also spelled “de Rijk”).

Fame and Fortune

Here the visitors find paintings that highlight Rachel Ruysch’s most productive years. This gallery showcases the colorful bouquets—teeming with fruits and insects, as well as flowers—that earned her international acclaim. The wall text describes her role as painter to the court of Johann Wilhelm II, Elector Palatine. Here visitors can see letters to and from the artist, and portraits of Ruysch on paper that reflect how contemporaries saw her. And, as it contains paintings from her later years, it is in this gallery that visitors see the signatures in which the artist includes her age at the time of completion.

Changing Perspectives

The final room features creative projects from contemporary artists and students at three colleges, which invites viewers to engage with her work in innovative ways. Visitors—at least the tech savvy among them—can arrange a hologram bouquet, then have their picture taken with it.

Rachel Ruysch and the Nature of Fame

Rachel Ruysch’s still lifes refer to full cycles of life, including decay and death. As she painted symbols of the transience of life, did she ever reflect on the longevity of her own renown?

Certainly, familiarity with her name and admiration for her artistic achievement dwindled in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. To quote Robert Schindler’s introductory essay in the exhibition catalog: “… while Ruysch was never forgotten, recognition of her work declined. As a woman artist, her appreciation was clouded in perceptions of gender, which in turn resulted in her large-scale exclusion from art historical narratives, scholarship, and museum displays. Today, Ruysch’s recognition still falls short of the fame she had achieved during her lifetime.”

Rachel Ruysch: Nature into Art makes great strides toward restoring the artist to her proper place in art history. Women Artists from Antwerp to Amsterdam, 1600–1750 and A Feast of Fruit and Flowers, among other upcoming exhibitions, will keep Ruysch’s name before today’s art lovers. Her ongoing inclusion in these, and future, art shows may finally cement Ruysch’s legacy. Thus perhaps her fame, now reignited, will long endure.

Three Unique Iterations

To recap, three museums will host this solo exhibition: Munich’s Alte Pinakothek, the Toledo Museum of Art, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The List of Works in the exhibition catalog makes clear that some artworks and/or objects will appear in all three venues. But in some cases, only one or two of the venues offer the opportunity to view a specific work. Of the 57 Rachel Ruysch paintings on display at the Alte Pinakothek, about a dozen will not travel to the show’s other iterations. And as noted above, the specific specimens in Munich cannot be transported to the US. The Toledo exhibition, at least, will also include specimens, albeit sourced from a different collection—with similar transportation challenges. It will be exciting to learn what other artworks and innovations the Ohio and Boston versions will introduce!

Collateral Elements

It must have been a thrill for the show’s earliest visitors to experience the installation of live flowers in the museum foyer. The unusual—and transient— “Flower Effect Tunnel” was the result of a partnership between Flower Council of Holland and floral designer Florian Seyd.

Visitors can pick up on site a free, tremendously helpful 48-page booklet, in English or in German. It offers overviews of each section of the show, and also biographies of every artist represented in the exhibition. The publication is accessibly written and very well illustrated. Readers can download it from the museum website, here.

In the outer and inner lobbies, even the rugs promote the show.

In the gift shop, visitors will find the exhibition catalog, Ruysch-infused cards, tote bags, sticky-note sets—and also wine. (The store at the Toledo Museum of Art already has Ruysch-related items for sale online. Visit this link to browse the early offerings!)

Rachel Ruysch: Nature into Art is on at the Alte Pinakothek until March 16, 2025. The exhibition then travels to the Toledo Museum of Art, where it will run April 13–July 27, 2025. Then the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston hosts the show from August 23–December 7, 2025.

For other reviews in English of Rachel Ruysch: Nature into Art, see: Apollo: The International Art Magazine, The Flora Journal, Fine Art Connoisseur, and The Art Newspaper.

For a list of upcoming shows to do with historic women artists more generally, see Museum Exhibitions about Historic Women Artists: 2025.

Erika Gaffney is Founder of Art Herstory. Follow Erika on LinkedIn, Facebook, and Bluesky.

More Art Herstory posts about Rachel or Anna Ruysch

Rachel Ruysch: The Art of Nature, by Stephanie Dickey

Rachel Ruysch’s Vase of Flowers with an Ear of Corn, by Lizzie Marx

Floral Still Life, 1726—A Masterpiece by Rachel Ruysch, by Lawrence W. Nichols

More Art Herstory posts about early modern Dutch women artists

Luisa Roldán: Escultora Real Review, by Olivia Turner

Alida Withoos: Creator of Beauty and of Visual Knowledge, by Catherine Powell

Women and the Art of Flower Painting, by Ariane van Suchtelen

Anna Maria van Schurman: Brains, Arts and Feminist avant la lettre, by Maryse Dekker

Curiosity and the Caterpillar: Maria Sibylla Merian’s Artistic Entomology, by Kay Etheridge

Books, Blooms, Backer: The Life and Work of Catharina Backer, by Nina Reid

Gesina ter Borch: Artist, not Amateur, by Nicole E. Cook

More Art Herstory exhibition reviews

Roma Pittrice: Women Artists at Work in Rome Between the Sixteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, by Alessandra Masu

Making Her Mark Leaves its Mark at the Art Gallery of Ontario, by Isabelle Hawkins

Sofonisba Anguissola in Holland, an Exhibition Review, by Erika Gaffney with Cara Verona Viglucci

Making Her Mark, An Essential Corrective in the History of Art, by Chadd Scott

Masters and Sisters in Arts, by Jitske Jasperse