Guest post by Stephanie Dickey, art historian

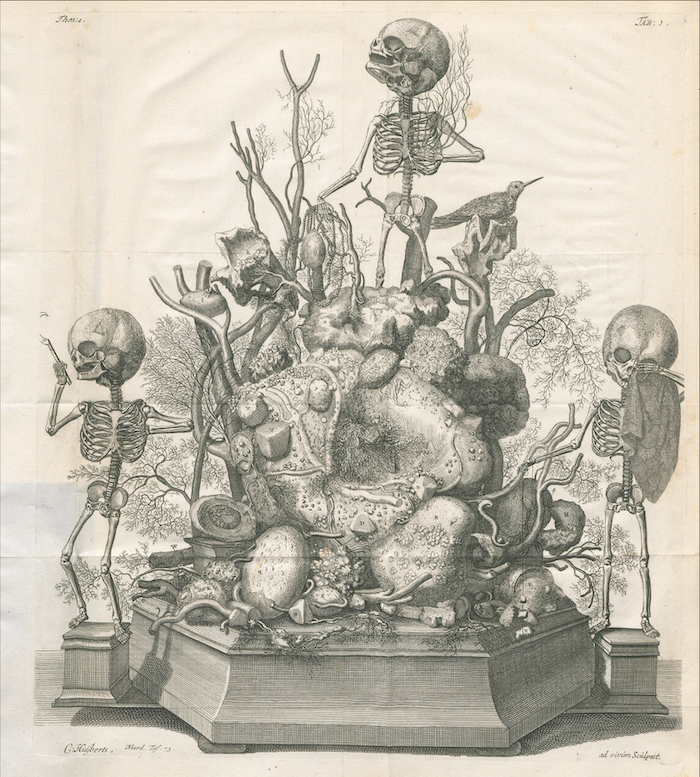

Picture this. The year is 1679. In a well-appointed townhouse in Amsterdam, a teenage girl enters her father’s study. On a table she sees a chilling diorama (Fig. 1): perched atop a wooden base, three infantile skeletons stand guard over a hoard of coral and bone. In a tall cabinet, embalmed body parts in glass jars line the shelves; dreaming faces, human and animal, peer at her through murky liquid. They do not frighten her; she has helped prepare some of them. As she leafs through a treatise on botany, her attention is distracted by a fly buzzing against a windowpane. She watches in fascination as the insect entangles itself in a shimmering spiderweb. Taking a notebook and chalk from her pocket, she begins to draw. She can’t stay long—she is overdue for a painting lesson with the famed still life artist Willem van Aelst.

This imaginary scene suggests the unique upbringing of one of the most successful women artists in early modern Europe. Nearly three centuries after her death, the still life painter Rachel Ruysch (1664–1750) is the focus of her first monographic exhibition, organized by the Alte Pinakothek, Munich, the Toledo Museum of Art, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The Toledo venue, which this writer visited, featured 50 of Ruysch’s 150 known paintings, along with paintings and drawings by related artists, documents, and naturalia. The show closed in Toledo on July 27, but moves on to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (see below for details). The richly illustrated catalogue, with essays by experts in natural science and art, examines Ruysch’s stylistic development, her patronage, the accuracy of her depictions of flora and fauna, and the intersection of art, colonialism, and scientific inquiry in her milieu.

A Child of Wonder

Rachel Ruysch was born in The Hague to Frederik Ruysch, a respected physician, anatomist, botanist, and collector of naturalia, and Maria Post, daughter of the renowned architect Pieter Post. When Rachel was eleven, the family moved to Amsterdam, where Frederik lectured on botany and anatomy. He belonged to an international network of scientific researchers and collectors, earning esteem for his novel methods of preserving plant and animal specimens. His collection of over 2000 preparations was purchased in 1717 by Peter the Great; some can still be seen in Saint Petersburg. For Rachel and her two sisters, home was a cabinet of wonders where art was valued as both a creative endeavor and a tool for scientific investigation. The exhibition includes several recently discovered works by Anna Ruysch (1666–1754), two years Rachel’s junior, who followed her example as a painter of fruit and flower still lifes (Figs. 2, 3).

Learning her Craft

According to Rachel’s first biographer, Johan van Gool, her father sent her to study with Willem van Aelst, whose studio was an easy walk from her home in Amsterdam. She quickly learned to emulate Van Aelst’s artfully casual bouquets (Fig. 4).

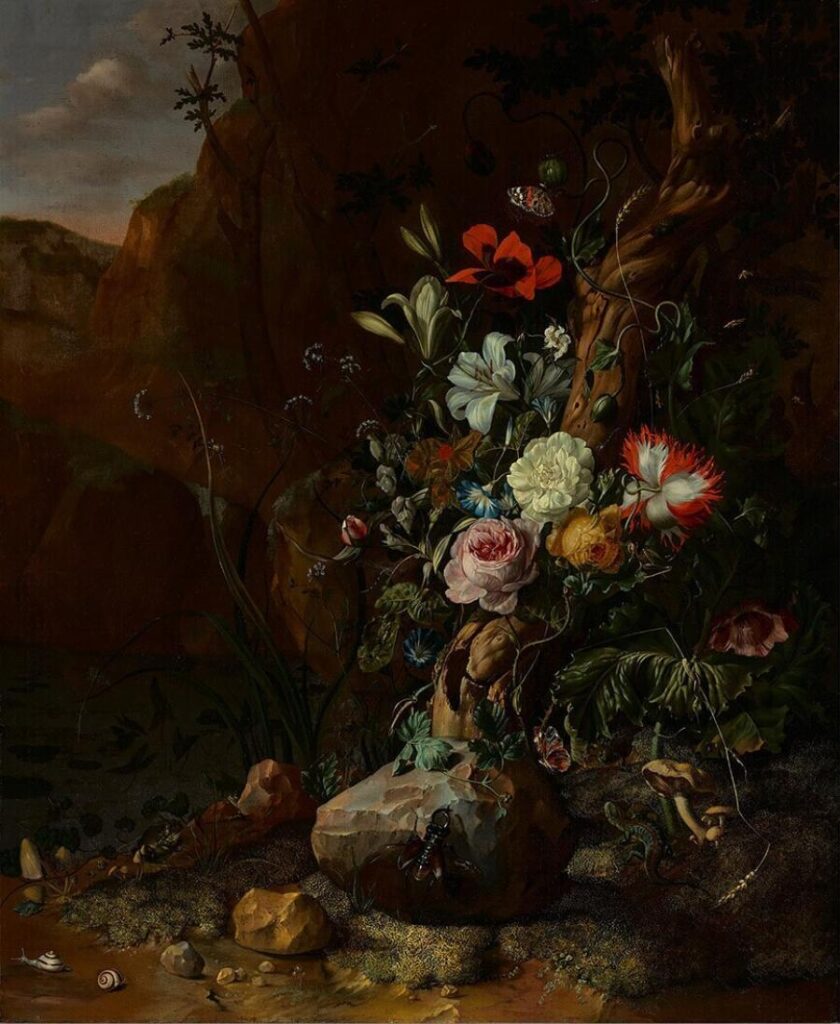

From another Amsterdam painter, Otto Marseus van Schrieck, both Rachel and Anna adopted a more fanciful motif: bosky forest floors where bright flowers bloom alongside rotting tree trunks (Fig. 5).

Rachel also painted nosegays, garlands, and arrangements of fruit, enlivened by a rotating cast of insects, birds, snails, rodents, and reptiles. Like Van Aelst and others, she composed bouquets of plants that bloom in different places and seasons, arranging blossoms in brilliant color harmonies that could never have existed in real time (Fig. 6).

Thus, more than records of first-hand observation, Ruysch’s paintings are also feats of deceptive artifice. How she designed her compositions remains a mystery, since only one drawing can so far be attributed to her. As Robert Schindler explains in the catalogue, it depicts a Surinam toad. This exotic amphibian captured the interest of naturalists for its unique method of reproduction. The female incubates its young in sacs on its back as shown in Ruysch’s drawing (Fig. 7).

A Global Menagerie

The term “still life” suggests placid beauty, but Ruysch’s lush compositions are alive with dramatic incident. Spent tulips, broken branches, drooping sunflowers, and dripping seeds threaten to destabilize precarious arrangements. Grasshoppers and caterpillars cling to slender stalks. Overripe roses teem with tiny ants. Impish lizards snap at butterflies or slurp the yolk of a broken bird’s egg (Figs. 8, 9; see also Figs. 16, 17).

As Katharina Schmidt-Loske explains in the catalogue, such behaviors are not always true to the creatures depicted. Neither is the blue tint Ruysch gives to the scaly skin of a green thornytail iguana, native to South America (see Fig. 15, below). This means that in some cases Ruysch must have studied preserved specimens—and invented narratives for them—rather than observing live animals.

In the Dutch Republic, the influx of novel species such as the iguana was a by-product of global trade. For collectors and amateur scientists, this brought new delight and urgency to the study of nature. In one intricate composition, Ruysch depicts 36 species of flora traceable to five different continents (Fig. 10). Even the casual observer must have recognized that this dense conjunction of oleander and convolvulus, jasmine and prickly pear cactus was not an everyday bouquet.

But the true admirers of such works would have been naturalists who took pleasure in identifying each specimen and discussing its properties. As Knaap reminds us in her catalogue essay, they benefited from a transit system that depended on the knowledge and labor of indigenous and enslaved people.

Inquiring Women

The scientific community included a substantial number of women. Ruysch must have met the wealthy collector and botanist Agnes Block, the first Dutch gardener to cultivate a pineapple in her greenhouse. Block, herself the subject of a recent book, employed a number of women artists, among them Maria Sibylla Merian, her daughter Johanna Helena Herolt, and Alida Withoos, to produce detailed illustrations of plants and animals (Fig. 11).

An Epic Career

The exhibition includes Ruysch’s first dated painting, created in 1681 when she was barely 17 (Fig. 12), and her last, age 83 (Fig. 13).

In the intervening seven decades, she earned fame and fortune unprecedented for a Dutch woman artist of her time. With her husband, the portrait painter Juriaen Pool (1665–1745), she also managed a busy household. In 1701, Ruysch and Pool were both elected to Confrerie Pictura in The Hague. Ruysch was the first woman admitted to this prestigious artists’ society. From 1708 to 1716, they served as court painters to Elector Palatine Johann Wilhelm II and his wife, Anna Maria Luisa de’ Medici, but were allowed to remain living in Amsterdam. For the Elector, Pool painted a family portrait in which he stands supportively behind his wife. One can imagine her seizing the brush to lay in the flowers herself (Fig. 14).

With them is the youngest of their ten children, Jan Willem, born when Rachel was 47 and named after their patron. Some of Ruysch’s most ambitious works were painted for the Elector at the rate of one per year. One enormous canvas piles fruit and flowers in a tour-de-force of virtuosity (fig. 15). Remarkably, Ruysch’s output remained constant through her childbearing years. Only after 1723, when Rachel and Juriaen won 75,000 guilders in a lottery, did she slow her rate of production.

Dutch collectors snapped up her work at record prices. Pieter de la Court van der Voort, a wealthy Leiden textile merchant, art collector, and avid gardener, paid the highest recorded price, 1300 guilders, for two paintings commissioned in 1710 (Fig. 16, 17). (For context, the average skilled worker earned around 300 guilders per year.) Reunited in the exhibition, they demonstrate Ruysch’s practice of creating pairs of paintings that balance fruit and floral motifs.

Rediscovering a Celebrated Talent

Rachel Ruysch, her father, her husband, and her sister Anna all lived exceptionally long lives for their time, dying at 86, 93, 80, and 87 respectively. A book of laudatory poems published shortly before her death in 1750 celebrates Ruysch for the beauty and lifelikeness of her creations. Such a volume was a gesture of esteem few artists received. As Lieke van Diensen describes in the catalogue, the collection opens with four poems by women authors, making it a testament to female literary accomplishment as well. Later that year, Johan van Gool devoted no less than 24 pages to Ruysch in his compendium of artist biographies, lauding her as “one of the greatest female artists of the known world.” Aert Schouman drew a portrait of the aged painter for illustration in the text (Fig. 18).

Ruysch’s lack of prominence in later scholarship probably owes as much to her specialty as to her gender. Classical art theory privileges narrative scenes drawn from human history, while dismissing still life, especially flower painting, as mimetic and decorative. Yet, as this exhibition shows, Ruysch’s breathtaking re-creations of nature on canvas are works of intellectual sophistication as well as consummate artistry.

The exhibition Rachel Ruysch: Artist, Naturalist, and Pioneer opens at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston on August 23, 2025; it will run through December 7, 2025. Previously the show ran as Rachel Ruysch (1664–1750): Nature into Art at the Toledo Museum of Art and at Munich’s Alte Pinakothek.

Stephanie Dickey is the author of numerous publications on Dutch art of the seventeenth century. Research interests include the art of Rembrandt van Rijn and his associates, the history of printmaking and print collecting, portraiture, and representations of women, gender and emotion. After retiring from Queen’s University (Kingston, Canada), where she held the Bader Chair in Northern Baroque Art, Stephanie is now a freelance art historian living in Indianapolis, Indiana.

More Art Herstory posts about Rachel or Anna Ruysch

Rachel Ruysch’s Vase of Flowers with an Ear of Corn, by Lizzie Marx

Rachel Ruysch at Munich’s Alte Pinakothek, by Erika Gaffney

Floral Still Life, 1726—A Masterpiece by Rachel Ruysch, by Lawrence W. Nichols

More Art Herstory posts about early modern Dutch women artists

Dutch and Flemish Women Artists—A Major Exhibition at the National Museum of Women in the Arts, by Erika Gaffney

A Year for Dutch and Flemish Women Artists

Historic Women Artists and Still Life at The Hyde Collection, by Erika Gaffney

Alida Withoos: Creator of Beauty and of Visual Knowledge, by Catherine Powell

Women and the Art of Flower Painting, by Ariane van Suchtelen

Anna Maria van Schurman: Brains, Arts and Feminist avant la lettre, by Maryse Dekker

Curiosity and the Caterpillar: Maria Sibylla Merian’s Artistic Entomology, by Kay Etheridge

Books, Blooms, Backer: The Life and Work of Catharina Backer, by Nina Reid

Gesina ter Borch: Artist, not Amateur, by Nicole E. Cook

A Clara Peeters for the Mauritshuis, by Quentin Buvelot