Guest post by Alexandra Kiely, independent art historian

An American painter and sculptor of animals, flowers, and landscapes, Matilda Browne (1869–1947) was celebrated during her lifetime but forgotten quickly afterwards. She has long been overdue for a revival, and it seems that she’s finally starting to get one.

Early Life and Work

Matilda Browne found her calling early on, growing up in Newark, New Jersey next to landscape painter Thomas Moran. Moran took time away from painting iconic images of the American West to encourage his young neighbor, and his wife Mary may have taught her as well. Browne later studied with Eleanor and Kate Greatorex (daughters of better-known Eliza Pratt Greatorex), animal painter Carleton Wiggins, and Tonalist Charles Melville Dewey, among others. She achieved success quickly, participating in her first significant exhibition at age twelve or fourteen.

As a young adult, Browne travelled to Europe with her mother from 1888 to 1892. She studied in Paris, then the center of the art world, and exhibited at the Salon of 1890. She also spent time in Holland, traditionally a hotbed for her chosen genres of animal and floral painting. Later on, she visited Puerto Rico in 1912, where she created vibrant images of the local scenery.

Matilda Browne in Connecticut

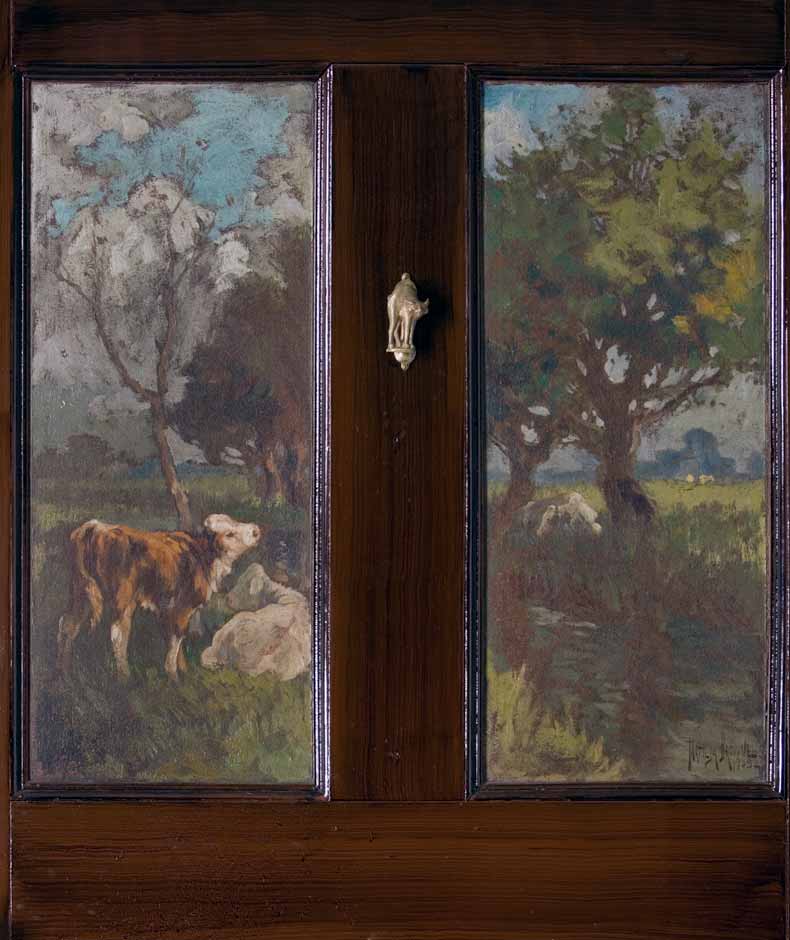

After returning from Europe, Browne lived primarily in Connecticut for the rest of her life. Many of her best-loved artworks depict local Connecticut settings. She became a member of the Old Lyme colony, a summer destination for American Impressionists centered at Florence Griswold’s boarding house. Although the group generally scorned female artists, these men made an exception for Browne, taking to both her professionalism and her good humor. In fact, she found such respect amongst artists like Childe Hassam and Willard Metcalf that she had the honor of being invited to paint on the house itself. Bucolic Landscape, a characteristic Browne image of two cows in a serene outdoor setting, adorns the double-paneled wooden door to Griswold’s bedroom.

Matilda Browne made, exhibited, and sold her work throughout a decades-long career, winning both awards and public acclaim. She participated in numerous artists’ associations and often showed at the National Academy of Design, though she was never elected a member. She also received an honorable mention in the 1892 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. The press generally praised her works, especially her animal paintings. Surviving reviews include the gendered comments typical of the time, mentioning her feminine appearance and supposedly masculine way of painting. However, this doesn’t seem to have held Browne back. Perhaps, her unconventional choice to specialize in both a stereotypically female genre (flower painting) and a stereotypically male one (livestock painting) made her difficult to label or pigeonhole.

Matilda Browne married Frederick Van Wyck (1853–1936) in 1917. (As a result, some records list her as Matilda Van Wyck.) Unusually for an early 20th-century female artist, marriage scarcely impacted Browne’s career. She did, however, collaborate with her husband on one project. Van Wyck, the descendant of early Dutch settlers in New York, wrote a book called Recollections of an Old New Yorker (1932), for which Browne made 120 black-and-white illustrations. Troubled eyesight probably contributed to the eventual end of her artistic career. Her last recorded exhibition took place in 1940, seven years before her death.

Style and Subject Matter

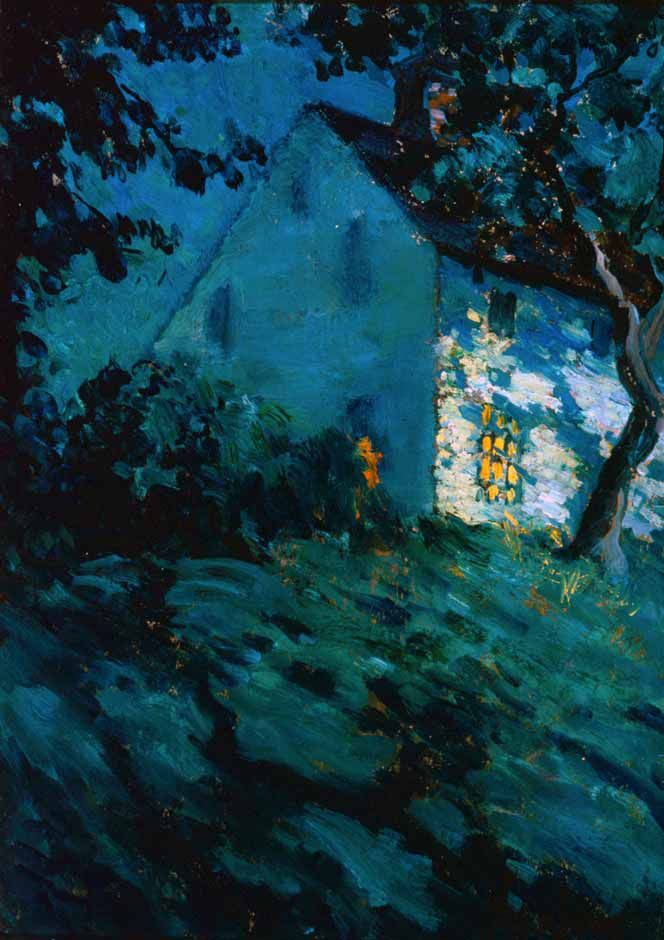

Matilda Browne’s style mixes the thick, confident, painterly brushwork of American Impressionism with influences of Tonalism and the Barbizon School. She typically used bright, eye-catching colors, though her occasional twilight scenes feature evocative shades of dark, moody blues.

Browne’s numerous animal paintings demonstrate her sympathy for and understanding of these creatures. She depicted farm animals with great sensitivity and sophistication, but without even a hint of sentimentality. She also created some lovely animal sculptures, though few survive. For obvious reasons, Browne was often compared to better-known French animalier Rosa Bonheur (1822–1899). Although Browne spent time in France during Bonheur’s life, there is no evidence that the two ever met. Like Bonheur, Browne got livestock models from Parisian animal markets, though it’s unlikely that she followed Bonheur’s lead in wearing pants to do so.

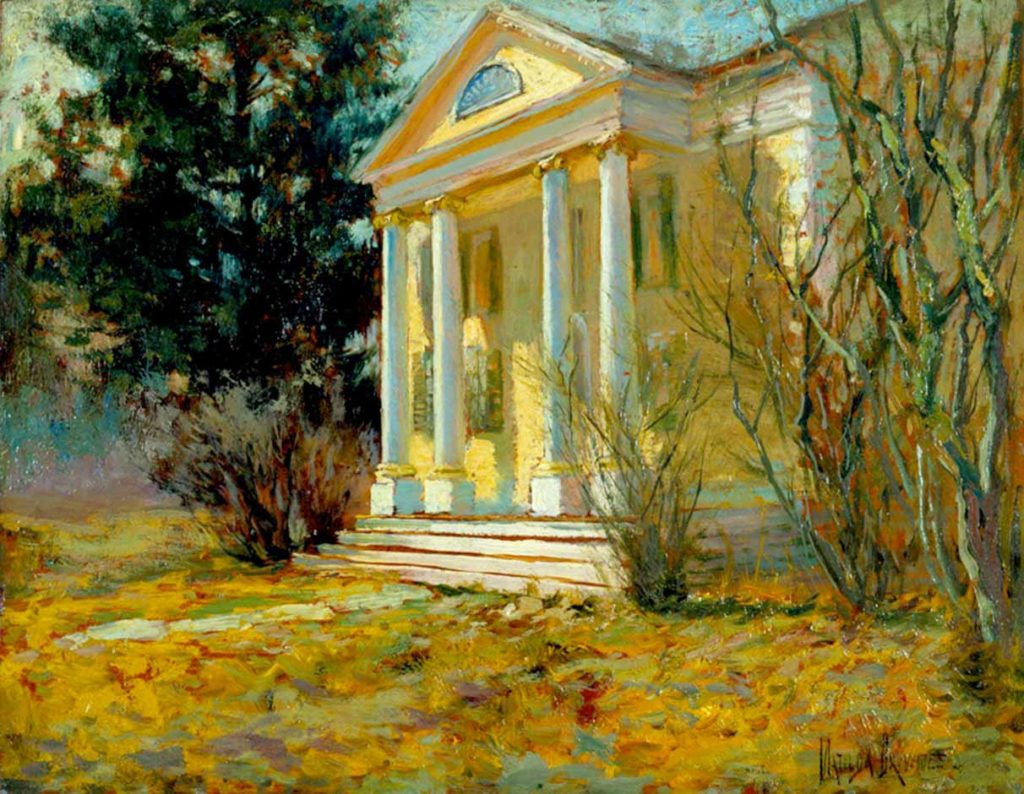

Although I enjoy Matilda Browne’s animal paintings, I personally prefer her floral works. Her abundant garden scenes, filled with fluffy, colorful flowers, evoke beautiful spring or summer days in the Connecticut countryside. Browne often populated her garden paintings with strong female figures, including her friend, the suffragette Katharine Ludington, or Helen Vorhees, the young daughter of her friend Clark Vorhees. Charming New England-style homes may fill out her compositions, as well. Browne’s floral still life paintings are also gorgeous. Tighter brushwork than she employed in her landscapes gives more detail to each individual flower. I equally enjoy her lace-like watercolors of floral subjects.

Idylls of Farm and Garden

As I’ve already suggested, Matilda Browne’s vibrant, beautiful artworks deserve greater recognition—and it seems that they’re starting to get some. In 2017, the Florence Griswold Museum organized Matilda Browne: Idylls of Farm and Garden, Browne’s first-ever solo museum exhibition. (“Idylls of farm and garden” is the perfect description of Browne’s work, by the way!) Located in Florence Griswold’s storied boarding house, this unique museum was a fitting venue for Browne’s first solo show since 1931. I initially encountered and fell in love with her work there in 2019.

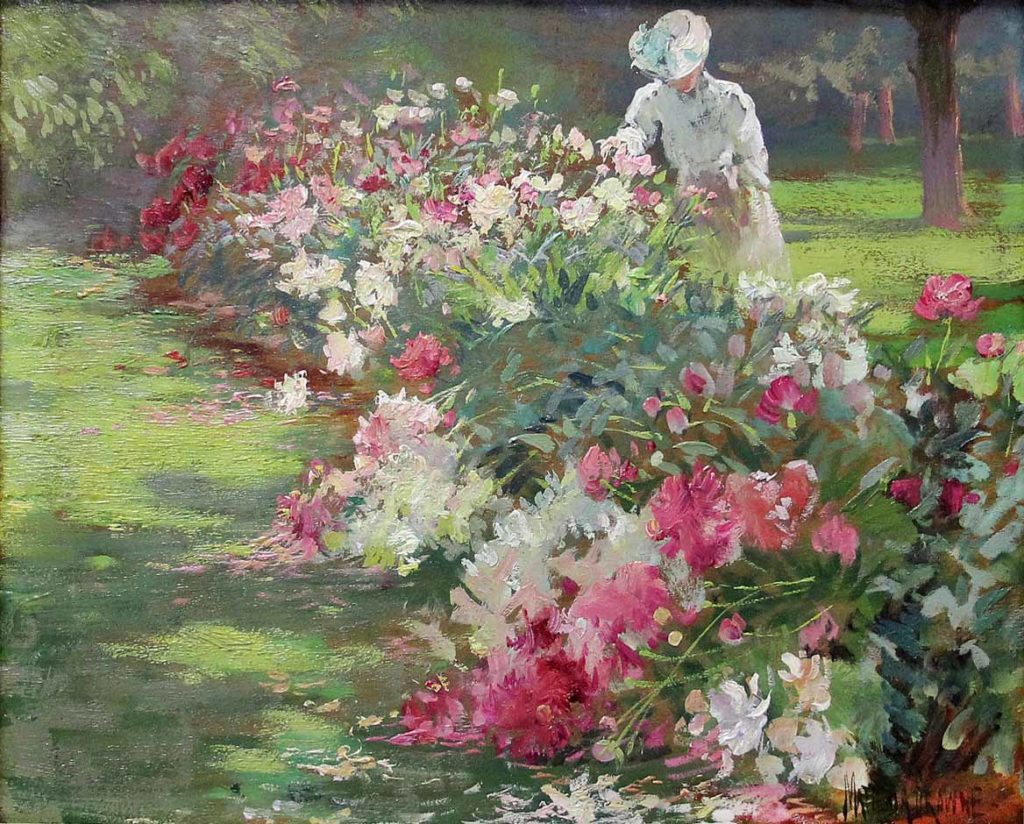

The Griswold’s acquisition of Browne’s Peonies in 2013 inspired Idylls of Farm and Garden. This stunning image depicts a pink-and-white flower garden in a verdant green landscape, tended by an elegantly-dressed woman. Bold, colorful, and inviting, Peonies demonstrates all of the qualities that make Matilda Browne’s art so appealing. That’s probably why it is her most reproduced artwork by far. The Griswold owns the largest collection of Browne’s works, further enhanced last year with the gift of her still life Zinnias and Gladiolas. Another standout in the Griswold’s collection is Miss Florence’s—a fond, even magical rendering of Griswold’s iconic yellow boarding house.

The Matilda Browne Renaissance

The research that independent art historian Susan G. Larkin and Griswold curator Amy Kurtz Lansing conducted for Idylls of Farm and Garden greatly expanded the once-scanty knowledge about the artist. The exhibition catalogue of the same title is definitely the best resource to learn about Browne and see a wide range of her works. The Bruce Museum in Greenwich, Connecticut also owns some of her works. Otherwise, the majority of her oeuvre remains in private collections. The fact that so many people want to keep Matilda Browne paintings in their homes is a well-deserved compliment, but it also contributes to her lack of recognition today. Changes in taste over time did her no favors, either. Her style and subject matter, particularly her animal paintings, had already fallen greatly out of favor by the end of her life. Within broader Impressionist scholarship, her legacy has probably also suffered from being a female working in America rather than France.

But perhaps that’s starting to change. In 2016, the year before the Griswold show, Browne’s work quite literally headlined Impressionism: American Gardens on Canvas. This New York Botanical Garden exhibition, which combined a display of American landscape paintings with real-life gardens inspired by them, included some of her paintings and even chose the Griswold Peonies to appear on the banner. Browne seems to have kept a garden in addition to painting them, and now she’s inspired some, too. That’s not a bad way to start a revival.

Alexandra Kiely is an independent art historian based in the greater New York area. Her work focuses on making art, architecture, and art museums understandable to a general audience. She is the author of The Art Museum Insider, a book that guides those without art history training to have more informed and empowered experiences with art. Visit her website, A Scholarly Skater, and follow her on Instagram.

Other Art Herstory blog posts you might enjoy:

An Introduction to Minnie Jane Hardman, by Hannah Lyons

Helen Allingham’s Country Cottages: Subverting the Stereotype, by Amy Lim

Women Artists from Savannah at the Telfair Academy Museum, by Julie Allen

The Cheerful Abstractions of Alma Thomas, by Alexandra Kiely

Marie Laurencin: Sapphic Paris, A Review, by Alice M. Rudy Price

Illuminating Sarah Cole, by Kristen Marchetti

Defining Moments: Mary Cassatt and Helen McNicoll in 1913, by Julie Nash

Women Reframe American Landscape at the Thomas Cole National Historic Site, by Erika Gaffney

Laura Seymour Hasbrouck, A Painter of the Hudson River School, by Lili Ott

Susie M. Barstow: Redefining the Hudson River School, by Nancy Siegel

The Rich and Complex Character of May Morris, Designer, Embroiderer, Jeweller and Writer, by Thomas Cooper

Marie Spartali Stillman’s The Last Sight of Fiammetta, by Margaretta S. Frederick

Visual Feasts: The Art of Sarah Mapps Douglass, by Erika Piola

Evelyn De Morgan: Painting Truth and Beauty, by Sarah Hardy

Anna Ancher’s Vaccination and Scientific Motherhood, by Alice Price

Celebrating Eliza Pratt Greatorex, an Irish-American Artist, by Katherine Manthorne

From a Project on Women Artists: The Calendar and the Cat Lady, by Dr. Lisa Kirch

The Life and Art of Dorothea Tanning, by Dr. Victoria Carruthers

Thank you for introducing Matilda Browne and her amazing talent. I plan to research more of her work and would give anything to view in person. Wonderful article.

I was so taken by Matilda Brown’s Saltbox by Moonlight that it inspired me to write a story. While visiting Elizabeth Garden I spied a woman standing at a lectern in front of a gathering of people beneath a tent. It turned out to be the poet laureate of CT. My friends had no interest in poetry so I had time to listen to one poem only. In the introduction to the poem about a garden the poet said she was inspired to write the poem after seeing a painting of a garden by Matilda Brown. It was at the Florence Griswold Museum that the poet and I saw the paintings that so moved us. I was stunned.