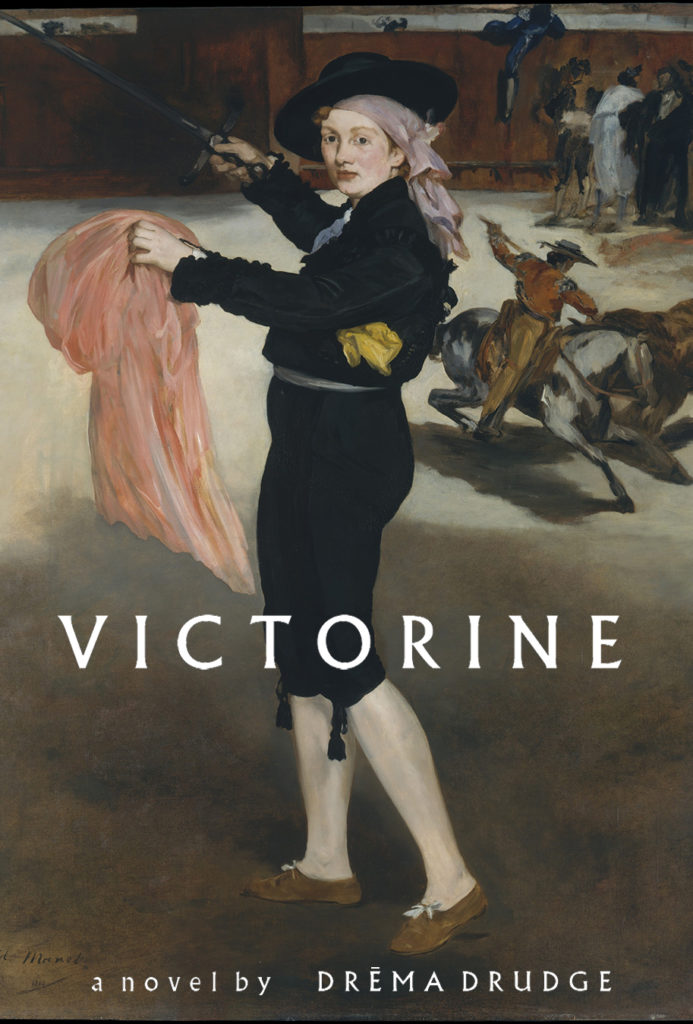

Guest post by Drēma Drudge, author of the new novel Victorine

When I first encountered Victorine Meurent, it was her as Olympia in Édouard Manet’s iconic painting, exhibited in Paris in 1865. This work scandalized both the public and the art community with its depiction of a defiant nude presumed to be a sex worker. As my professor turned on the classroom lights after his presentation, I couldn’t shake the feeling that the red-haired woman in the painting was trying to communicate with me.

The next summer found me examining the painting at Paris’ Musée d’Orsay, trying to figure out what it was she wanted to tell me. She had also posed, I learned, for Manet’s equally “scandalous” painting of the time, Dejeuner sur l’herbe (Luncheon on the Grass), also on display at this museum. Meurent, nude again.

If history remembers Victorine Meurent, it’s as Manet’s favorite model. She was, however, an artist herself. Her work was included in the prestigious Paris Salon multiple times, no small feat for someone poor and female. Her self-portrait was even exhibited in 1876 at the Salon, when Manet’s work was rejected.

Meurent lived with a woman, Marie DuFour, for the last twenty or so years of her life, calling into question the accuracy of those rumors that Meurent really was a sex worker, that she was a beggarly alcoholic who traded on her past “fame” and died young. She actually lived to be 83.

According to Meurent in a letter she wrote Manet’s widow in 1883, she earned a living painting until she injured a finger on her right hand. There’s also evidence that she taught music lessons.

Upon learning that the only painting of hers known by most of the world to exist is Palm Sunday, which was recovered only in 2004, I wanted to write a novel returning her to the world as an artist. I thought, maybe that’s what she wanted of me. If only I could see the paintings she had created, maybe I could learn more about who she was. In lieu of that, I’d have to use my imagination. Or would I? I researched her as much as I could, but there wasn’t much to know. So I plunged ahead with what information I had at hand.

For instance: Wikipedia insinuated that Victorine had been a lover of the artist Alfred Stevens. That led me to his paintings of her. Though she appeared in more paintings of his than I explore in the novel, and though he was overly fond of red-haired models, in some of them he named his model, so in those we know the model is Victorine. Those paintings gave me another source to study who she was. It also gave me fodder for the war section of the novel. Given how little is known about her, these paintings filled some gaps, and helped me know what she was up to, when.

We have the barest of facts about Meurent: she was born February 22, 1844. Her middle name was Louise. We know where she was baptized (St. Elisabeth) and her parents’ names (Jean Louis Étienne Meurent and Louise Thérèse Lemesre). We have no evidence that she ever married, and we know that she went to art school at the Académie Julian after she sat for Manet.

Oh, but what I wanted above all was to examine Victorine’s brush strokes, her choice of subject, the colors she favored. Her style. Was it true that she and Manet went their separate ways because she chose a more traditional route to the Salon? Only her paintings could tell me—and they were lost.

One frigid February morning while I was writing Victorine, a young boy introduced himself into my story. He said his name was Pug. He charmed me (and Victorine in my story), so we let him stay. Much later, I discovered another recovered painting of hers in Paris that few seem to know exists: Le Briquet, featuring a boy eating a piece of bread. That was Pug, I had no doubt.

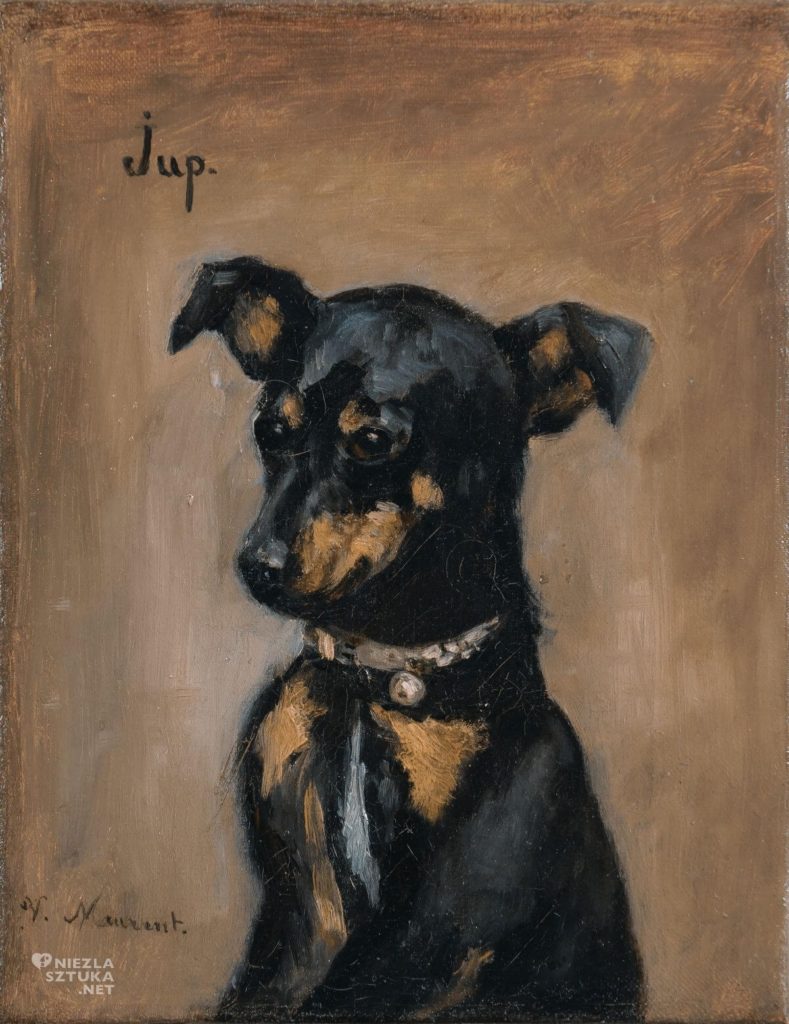

In my novel, Victorine’s mother has a dog she cares about more than she does her daughter. Talking with a staffer at a museum in France brought to light yet another recently found painting of hers, one of a small terrier named Jup. I hadn’t known of the painting (few do even now) when I wrote of the dog, prompting me to ask my publisher for time to insert the dog’s actual name into the book before publication. That felt like giving yet another piece of herself back to Victorine’s history.

However, I didn’t give up entirely the notion of finding more paintings of her. I put Google alerts on my phone; I ran down every tiny lead I could find on the internet that might lead to something else. I began to hear hints, hints that I at first dismissed.

Someone online made a claim about the rediscovery of an important painting of Victorine’s. But they didn’t say what it was, or where it had been found. I waited for the media to run with it, but either it didn’t hear or didn’t care. That broke my heart and made me more determined than ever to find it. While the circumstances of its actual recovery are still veiled, a photo of painting came to my awareness when my husband, my ever-devoted research assistant, phone in hand, asked me a question he had asked me a dozen times before that hadn’t amounted to anything in our quest for paintings by Meurent: “Have you seen this?”

This time, I had not. This time, I thought he might have actually found it: he had pulled up an auction description containing—be still my heart—a photo of a self-portrait of Victorine. More specifically, the self-portrait: Victorine’s self-portrait from the 1876 Salon, the exhibit in which she had “bested” Manet. I expanded the picture to be sure her signature was on the painting; it was. This led to a hasty email from me to the owner of the painting, a French gallery owner, who allowed me to use the portrait on the back of my novel. To the best of my knowledge, this is the first time the painting has ever been published beyond in an auction catalog.

This recovered painting is particularly important because Victorine’s self-portrait would have been a significant act of defiance and self-delineation in a rapidly changing art world. Its recovery will allow art scholars to compare it with the more than thirty paintings of her by male artists, and to see her as she saw herself. That its existence has not been brought to the art world’s attention even after its rediscovery underlines one of the issues my novel aims to raise: women who in real life are multifaceted and multitalented, are often reduced to mere objects of the male gaze. May my novel allow Victorine to once again take her rightful place in art herstory.

Drēma Drudge is a novelist, freelance writer, and educator who lives in Indiana with her husband, writer and musician Barry Drudge. Her fiction has been published in The Louisville Review, Mused, ATG, Penumbra, Woolf Zine, and The Same, among other publications. She is a regular contributor to the popular Chicken Soup for the Soul series. Her new novel Victorine (Fleur-de-Lis Press, March 2020) tells the compelling story of a daring female artist and model of late nineteenth-century Paris.

If you liked this Art Herstory blog post, you might also enjoy:

Museum Exhibitions about Historic Women Artists: 2026

Blanche Hoschedé-Monet: An Artist in Her Own Right, by Rebekah Hoke Brown

Unpacking the Exhibition: Blanche Hoschedé-Monet in the Light, by Haley S. Pierce

Marie Laurencin: Sapphic Paris, A Review, by Alice M. Rudy Price

The Rich and Complex Character of May Morris, Designer, Embroiderer, Jeweller and Writer, by Thomas Cooper

Marie Spartali Stillman’s The Last Sight of Fiammetta, by Margaretta S. Frederick

Visual Feasts: The Art of Sarah Mapps Douglass, by Erika Piola

Evelyn De Morgan: Painting Truth and Beauty, by Sarah Hardy

Anna Ancher’s Vaccination and Scientific Motherhood, by Alice Price

Celebrating Eliza Pratt Greatorex, an Irish-American Artist, by Katherine Manthorne

Thérèse Schwartze (1851–1918), by Ien G.M. van der Pol

Marie Laurencin and the Autonomy of Self-Representation, by Mary Creed

The Many Faces of Suzanne Valadon, by Dr. Suzanne Singletary

Anna Boberg: Artist, Wife, Polar Explorer, by Dr. Isabelle Gapp

The Theatrical Wonders of Jeanne Paquin’s Belle Époque Parisienne, by Julia Westerman

For the complete list of Art Herstory blog posts, visit this link

Many thanks for having me guest post today. I appreciate it!

Ms Drudge, thank you so much for posting this article. I was aware that Miss Meurent had done some painting but had heretofore never seen any of them. I was amaze by the quality of her work. I really didn’t expect much since her paintings have received little historical mention; however, it is clear to me, after seeing the pictures you have included in your post that she was an excellent artist. The information you provide in your post was also of immense satisfaction – both informative and very well written. I have passed on this link to friends who share my interest in this subject. I wish you success with your book. I’m sure it will do well.

Thank you so much for your kindness. Getting out the word about Victorine’s art versus her just being made art of is a passion of mine.

I’m so glad you, too, recognize her talent. I hope even more of her work will be rediscovered!

If you’d like to see my book trailer, please visit http://www.dremadrudge.com.

Thanks again for sharing information about my book. I’m grateful!

Drēma

Ms. Drudge, There is a movie available for free on You Tube called ‘The Impressionists’. It is in three parts. Victorine is characterized in the film. This film is one of the finest historical presentations on the subject of “impressionism” I have ever seen. I pass it on in the event that you are not already aware of it. If you haven’t seen it please trust me – you will absolutely love it. Simply do a search on You Tube for ‘The Impressionists’.

Thanks! I will check it out.

All Best,

Drēma

Thank you for bringing attention to the novel, with which I had not been familiar.

Please note also the exceptionally fine nove,

A Woman With No Clothes On” by Vesna R Main, Delancy Press, London, 2008.

Bonjour,

je travaille sur la peintre Marie Bracquemond et j’ai ainsi croisé la route de Victorine Meurent. Il semble qu’elle ait eu en 1861 un fils prénommé Louis dont je n’ai pas trouvé trace ni de la naissance ni du décès et aussi quelques autres informations. Je tenterai de lire votre livre pour y découvrir un peu plus sur Victorine.

Marie-Françoise

blog “ellesaussienbretagne”

Marie, thanks so much for your kind comments. I’m sorry that I don’t speak French.

Marie Bracquemond is a wonderful painter. I look forward to reading your writing about her.

I have never heard that Victorine had a son. I’d love to talk with you more about this. Please feel free to email me at: drema@dremadrudge.com.

All Best,

Drēma

Hello! I was delighted to find here so much information on Victorine. I am presently writing a historical novel in which she makes a couple of brief appearances, and historcal accuracy is, of course, necessary. Besides the bare facts, which are few, it is good to have a better picture of her as an individual. Thank you for your research!

David, I’m so glad I could be helpful. I only wish there were more to know. Please keep me posted about your novel; I’m intrigued. My email is drema(at)dremadrudge.com.

And my apologies for having not noticed your remark before now. Happy Writing!

Hello, Drema,

I had forgotten I had even communicated with you. My novel is complete, and Victorine plays a significant part in the historical fiction part of my story, which takes place when Victorine is aged 19 to 24. I confess I have taken some liberties, but they have been loving and respectful. I would be delighted if you would read my novel, THE YELLOW ROOM, A TALE OF INNOCENTS. (available on Amazon and deliberately priced at their minimum. Please tell me what you think if you should happen to purchase a copy.

Hi David, I’m intrigued about your novel! Please keep me posted on its progress: drema(at)dremadrudge.com.

I wish there was more to know, but at this point we don’t know much about her.

The research was my pleasure!

Thanks so much for your kind comment.

Hello,

I try to write in english but it’s not easy for me. I just find your answer and I will join you directly on your EM.

You can read something about Victorine on my blog “ellesaussienbretagne” in the article about Marie Bracquemond and use “google traduction”. My idea is that Victorine was obliged to earn money after having a child out of marriage so became a model for painters.

Marie-Françoise , Rennes, France

Thank you so much, Marie. I will certainly take a look! Your blog sounds wonderful.

Thank you!!! I first encountered Victorine at the National Gallery, where she made me sit down on a bench for a 25-minute confrontation about what I was starting at, the most personal response I’d ever had to great art. When Eunice Lipton’s book came out in 1999, I phoned her and had a long, lovely talk. When the palm painting was discovered I printed it out on fine paper and put it on my wall.

So this, over 20 years later, is a great event to me. Thank you.

Oh Vid, I know exactly what you mean! She demands to be noticed, doesn’t she?

I’m envious of your talk with Eunice, and I, too, have printed Victorine’s artwork. I’m so glad I could share these wonderful paintings with you.

I have something interesting to add to all this she was noticed enough for someone to make a bronze head of her in the late 1800s I know this because I have this in my possession not sure of the maker but maybe her father because he was a paintier of bronze

какие интернет провайдеры есть в моем доме [url=http://www.domashnij-internet-voronezh.ru/#какие-интернет-провайдеры-есть-в-моем-доме]http://www.domashnij-internet-voronezh.ru/[/url].