Guest post by Erika Piola, Library Company of Philadelphia

At her death in 1882, African American Quaker educator, civil rights activist, essayist, and artist Sarah Mapps Douglass (1806-1882) requested that all of her private correspondence, along with her “lectures on anatomy and natural history to mothers,” be destroyed. Douglass’s drawings constitute some of the documents of her less public life that still remain in existence. Although not vast in number, they constitute works of great importance to the history of American art (Fig. 1). While past scholarship about Douglass acknowledges her pieces as representations of some of the earliest signed works of art by African American women, more recent scholars, such as Mia Bagneris, Katherine Bondy, and Britt Rusert, have further explored the historically generative role of Douglass as an artist. Their scholarship informs this post.

Douglass’s Family

The life of an artist necessarily affects her work. Douglass was born into a free Black elite family of Philadelphia. Her family engaged in social and political activism and had a genius for art. Douglass’s Quaker mother Grace Bustill (1782–1842) labored as a milliner, an educator, abolitionist, and civil and women’s rights activist. Her father Robert Douglass (1777–1849), an elder of the First African Presbyterian Church, worked as a hairdresser. Like her mother, he advocated for the abolition of slavery and education and civil rights for the Black community. Douglass was one of six children. Her brothers, Robert Douglass, Jr. (1809–1887) and William Penn Douglass (1816–1839), together with her cousin, David Bustill Bowser (1820–1900), led careers as artists.

Life of an Educator and Quaker

From an early age, education and the Quaker faith affected the formative years of Douglass. Taught first at a school for Black children administered by white Quaker Arthur Donaldson, she later attended one established in 1819 by her mother and African American businessman James Forten (1766–1842). Within the decades to follow Douglass became a revered educator. She taught for over fifty years, primarily in Philadelphia. She administered her own school for Black girls in the 1830s, then served as the teacher of the Primary Department for Girls at the Quaker-sponsored Institute of Colored Youth from the early 1850s until her retirement in 1877. Not content with the traditional courses reserved for female students, Douglass’s curriculum grew over the years to encompass not only grammar, spelling, and writing, but also Latin, science, and math. Her educational methods involved her students compiling friendship albums, as well.

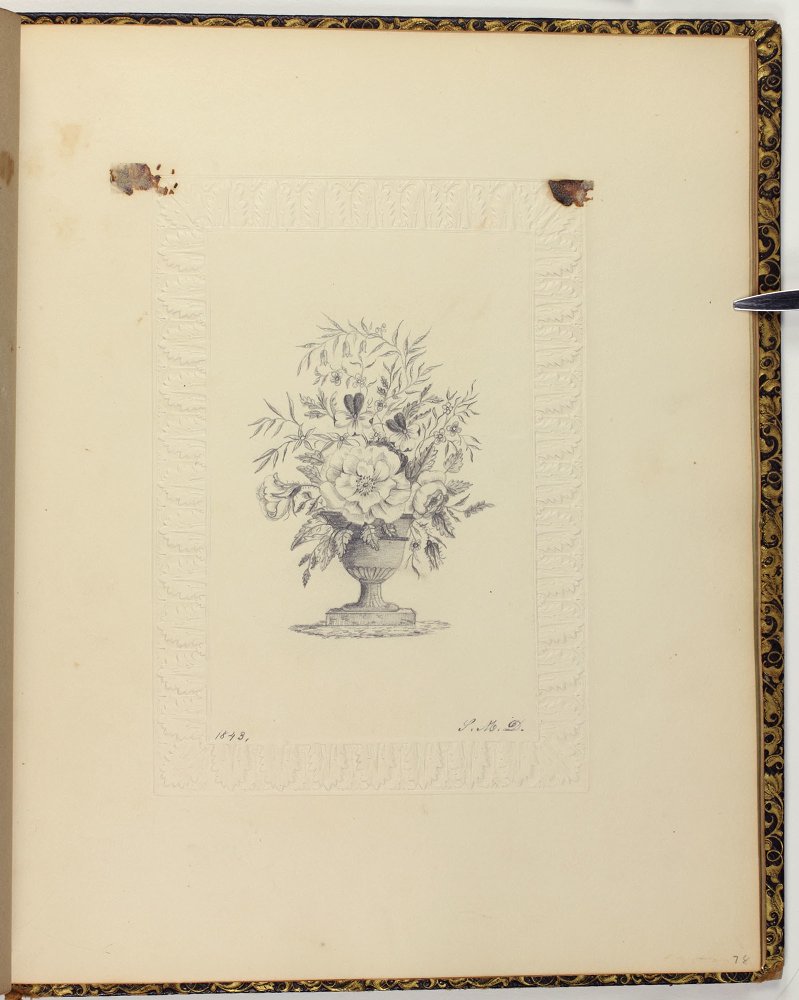

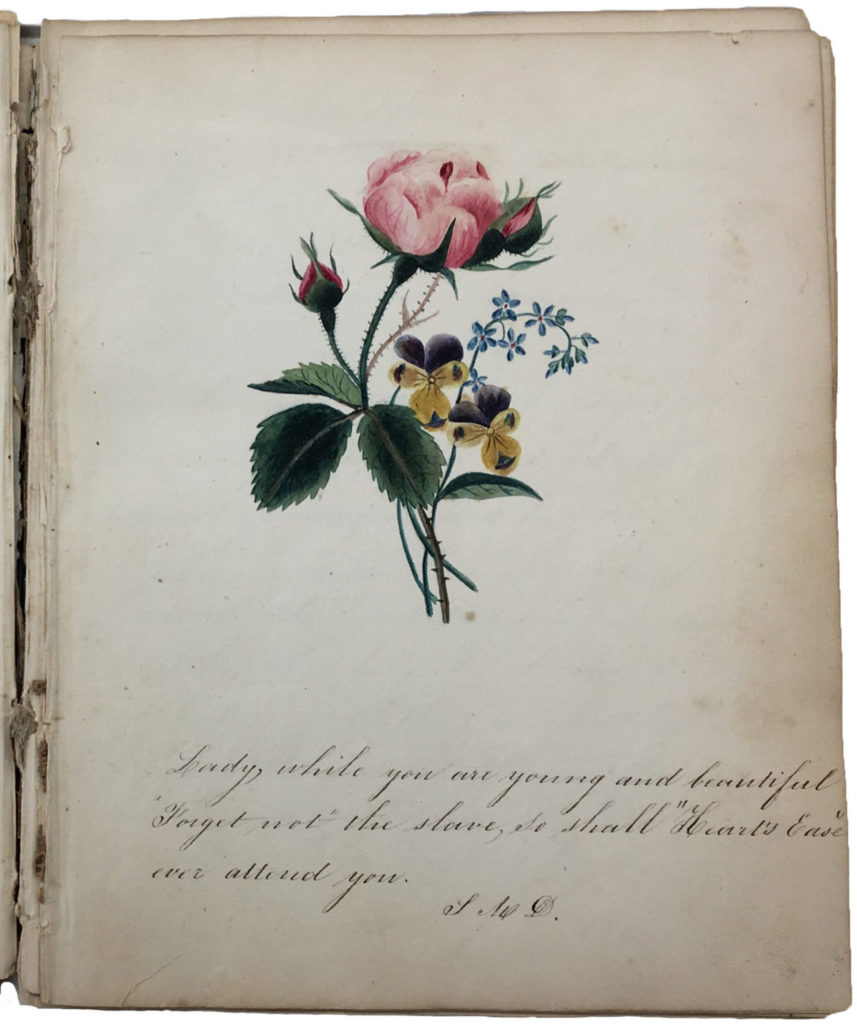

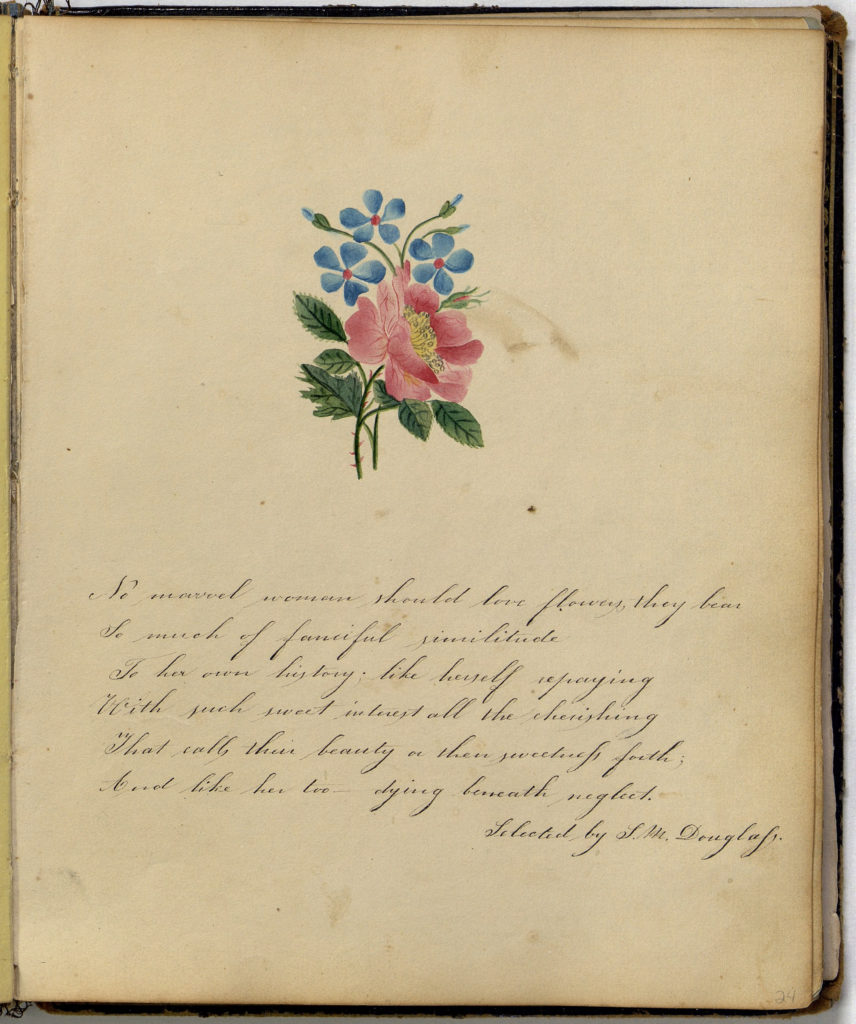

The albums, composed by their own hands and by others in their social networks, including Douglass, contained transcribed and original essays, poems, prose, and works of art (Fig. 2–3). Concurrently, she would publicly condemn the racism that she and her mother faced within their chosen faith. The Society of Friends established educational institutions for the African American community, but required Black Friends to sit on segregated benches during Quaker meetings and did not include Black Friends in their membership.

Continuing Education

Douglass continued her own education while a teacher. She attended classes on anatomy, physiology, and hygiene during the 1850s, initially as the first Black student at the Female Medical College of Pennsylvania, and later at Penn Medical College. Soon thereafter she publicly lectured on the subjects to audiences of women, but occasionally men, too. Her lectures utilized illustrations, possibly of her design, and an anatomically correct female mannequin. As described in a July 23, 1859 issue of the Weekly Anglo-African, “They were not mere details of scientific facts, but were enriched by numerous and beautiful illustrations, well calculated to elevate the attention of many on whom theories, however grand and inspiring, are lost.” All this time, students, young and adult, as so eloquently remembered by African American minister and scholar Dr. Alexander Crummell (1819-1898), “received from her the ripe instruction of her well-cultivated mind.”

Marriage

During this period, in 1855, she married a widower, abolitionist Episcopal Rev. William Douglass (ca. 1804–1862), and became a stepmother to his nine children. Married life proved difficult for Douglass. Her husband fell ill soon after their marriage, she had a strained relationship with her stepchildren, and household income remained tight. In correspondence, she described it as, “the years that I was in that school of bitter discipline, the old parsonage of St. Thomas.” Within less than a decade, she would be widowed.

Political, Social, and Literary Activism

Not only an educator, Douglass continued her family’s political activism. During the 1830s, she proactively engaged herself in the anti-slavery movement. She founded the anti-slavery Female Literary Society, whose members ascribed to “mental feasts” through group discussions of their writings. She joined the interracial Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society and served in official roles until its disunion in 1870. Douglass moreover published essays and poetry in anti-slavery publications like The Liberator. She formed life-long friendships with Quaker, anti-slavery and women’s right’s activists and sisters Angelina Grimké Weld (1805–1879) and Sarah Grimké. With them, she confronted racism in society and their faith, as well as advocated for the abolition of slavery and civil rights for African Americans and women.

Her activism never waned into her middle and later years. In 1849, she started the Philadelphia Women’s Association to support Frederick Douglass’s newspaper, The North Star. And between 1859 and 1865, Douglass began a literary circle in her name, helped found the Stephen Smith Home for Aged and Infirmed Color Persons, and served as Vice President of the Women’s Pennsylvania Branch of the American Freedmen’s Aid Commission in support of the care of formerly enslaved children.

The Educator and Activist Artist

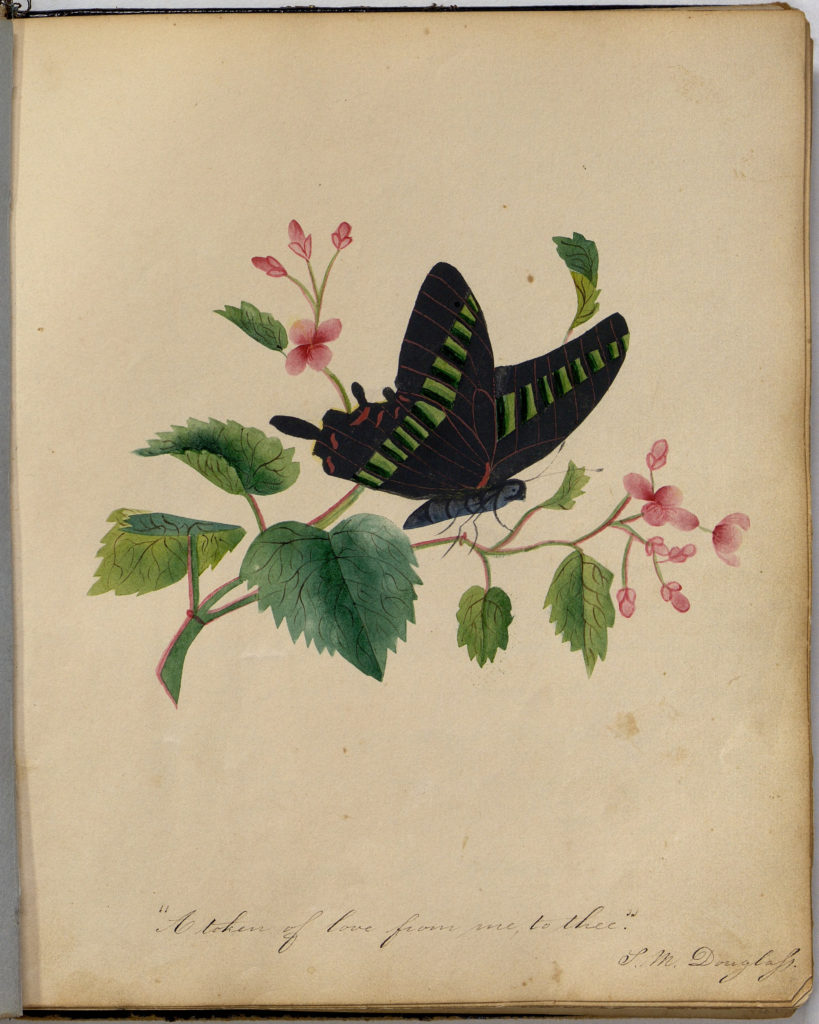

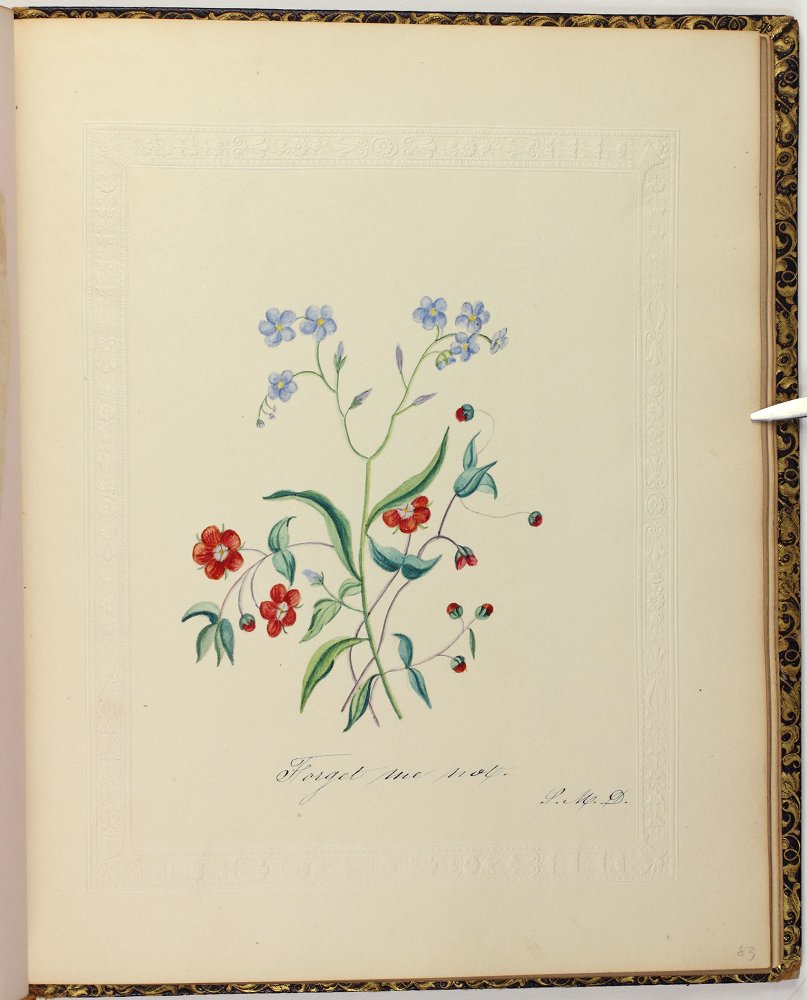

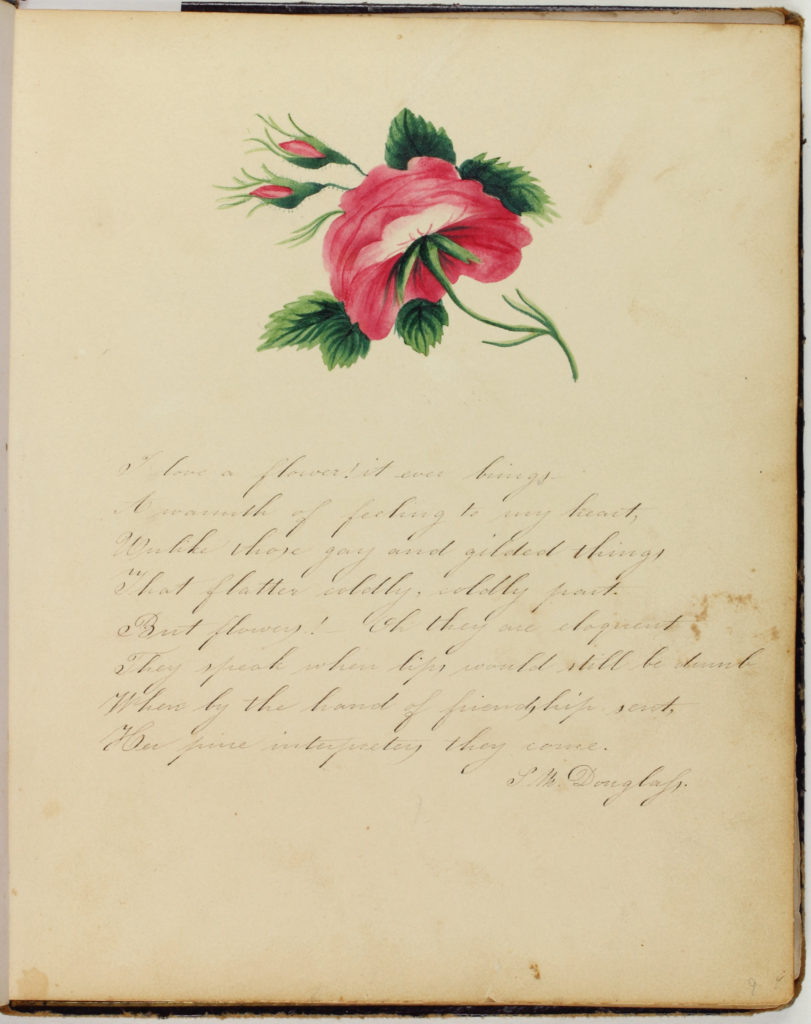

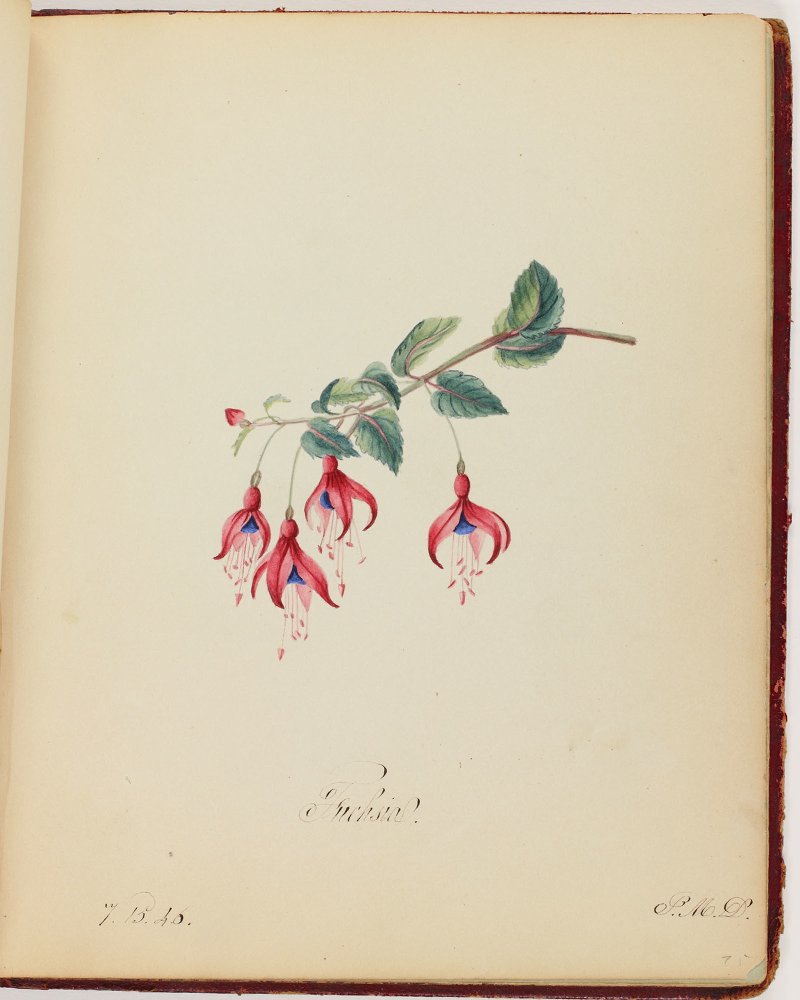

Douglass’s artwork reflects her identity as a free Black woman, her career as an educator, and her political and social activism. Predominantly found in the antebellum friendship albums of four women and girls, three African American, and all with ties to the anti-slavery community, her known extant work comprises eight drawings. Often accompanied by poetry, the pieces date to circa the 1830s and 1840s (See Figs. 4–5). The artworks depict stems of flowers; floral bouquets, nosegays, and arrangements; and a butterfly. The floral subjects include roses; camellias; pansies; and forget-me-nots. Likely a self-trained artist primarily, Douglass also drew inspiration from painting manuals like James Andrews’s 1836 volume Lessons in Flower Painting: A Series of Easy and Progressive Studies. It was from this book that she rendered her July 1845 image of a fuchsia in the album begun about 1833 by her former student Mary Anne Dickerson (1822–1858, Fig. 6).

A Flower is Not Just a Flower

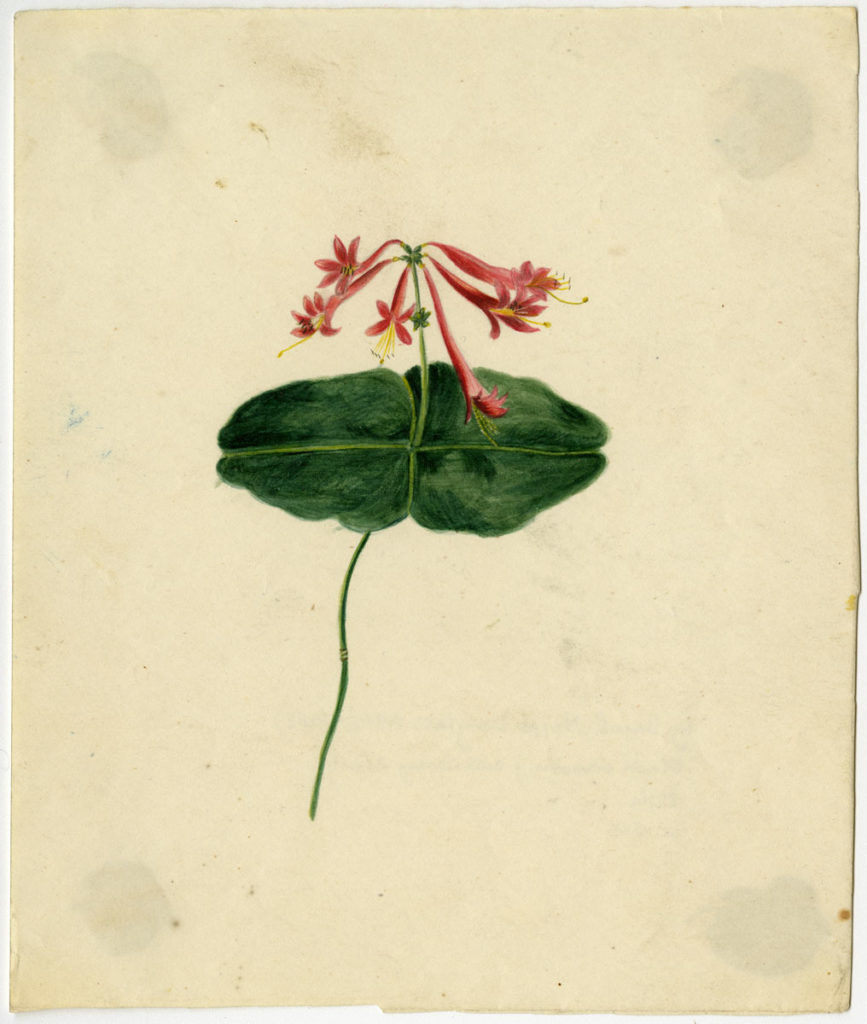

Too simply described as works created as signs of female education, gentility, and sentimentality, scholars of her paintings, like Jasmine Cobb, have observed that cultural presuppositions about thinking and feeling would mask the conscious and unconscious political purposes behind the sentimentalism in African American women’s writings and artworks. Douglass’s butterfly hand painted in black; the contrasting symbolism of a delicate nosegay of camellia and forget-me-nots depicted with a stem covered in thorns; and a solitary, yet vivacious sprig of honeysuckle belie any understanding of them as compositions reflective only of middle-class refinement in accordance with the culture of the language of flowers (Figs. 1, 7, 8).

Artists imbue their art with a multitude of possible meanings that can be received by those who view their work. Whereas Mia Bagneris describes Douglass’s art as radical floriography espousing equality, Britt Rusert explores the drawings in terms of their embodying an intersection of floral aesthetics and the science of natural history. Be it a camouflage device for (in)visibility or evidence of a liminal space in which the individual’s interior life rebels against sentimentality as discussed by Katie Bondy, a flower painted by Douglass is not just a flower when placed in the context of the image representing the surveilled antebellum Black female body in private and public.

Not Only Botanical Art

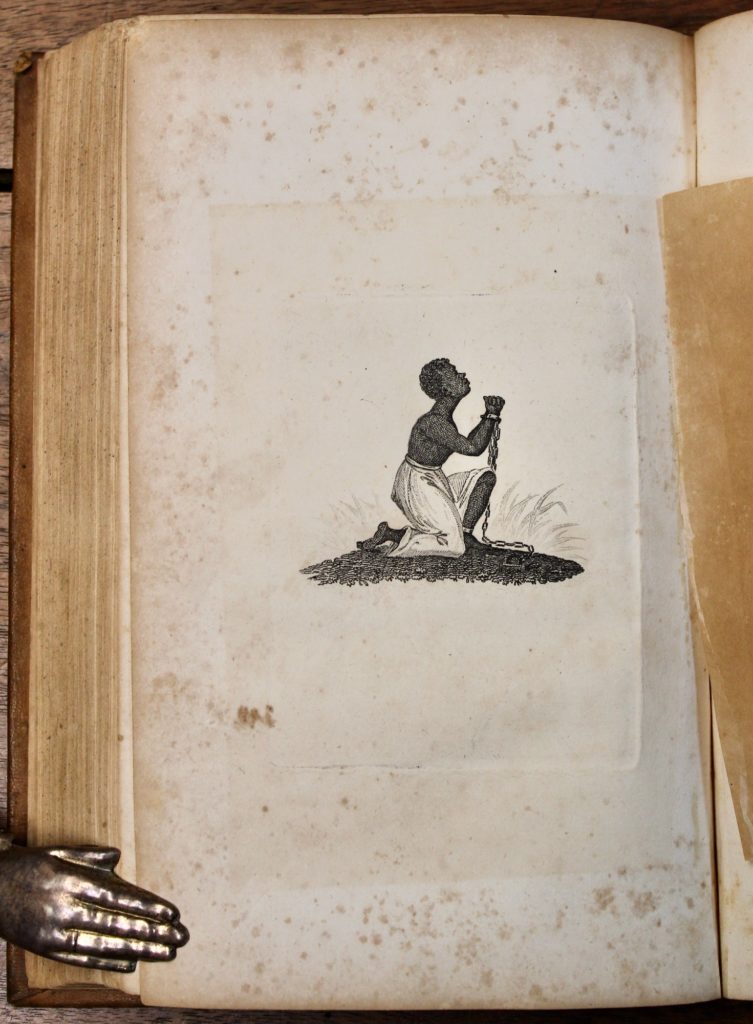

However, we know that Douglass’s first recorded work of art was not of a botanical, but was rather sociopolitical in nature. In 1833, she sent a sketch of an enslaved woman to Quaker abolitionist and author Elizabeth Margaret Chandler (1807–1834). The image of the “Am I Not A Woman and Sister” kneeling enslaved woman figure that Chandler introduced in 1830 into the visual culture of the abolitionist movement (Fig. 9) likely influenced the sketch, known only through a reference.

Douglass did not confine her art to only “gifts” for friends and students; she sought compensation for her work. In 1844, advertisements in the Pennsylvania Freeman for her artist, brother Robert Douglass, Jr. incorporated the notice “Marking on Linen. Silk, &c. by S.M.D.; specimens may be seen in the gallery.” Reasonably, the funds she earned from her art supported the school she solely administered at the time.

Artist in Senior Life

As with her career in education and activism, Douglass continued her work as an artist through her senior years. In 1874, letters in the Weld-Grimke Family Papers at the William L. Clements Library show she still made art on textiles. She wrote about designing album quilt patches for the son of longtime friend Angelina Grimké Weld.

In a family history published in 1925, author and Douglass extended relative Anna Bustill Smith remarked in relation to her brother, Robert, “His sister Sarah Mapps Douglass, was much better known in as much as she taught school for 60 years.” Our “knowing” Douglass and her formative role as an educator and artist from and within the Black community continues to grow and evolve. Nuanced study of not only her mental feasts, but also her visual feasts, enriches our further understanding of the sociopolitics and dynamism of American art by nineteenth-century women and African American artists.

Erika Piola is Curator of Graphic Arts and Director of the Visual Culture Program at the Library Company of Philadelphia. Her research interests include the antebellum Philadelphia print market, nineteenth-century ephemera, and American visual culture and its intersections with African American and women’s history. She is currently completing a chapter about Philadelphia printseller Sarah Hart for Female Printmakers, Publishers and Printsellers in the Eighteenth Century: The Imprint of Women in Graphic Media, 1735–1830 to be published by Cambridge University Press.

Other Art Herstory blog posts you might enjoy:

Emma Stebbins, Anne Whitney and Vinnie Ream: American Women Sculptors of the Nineteenth Century, by Maria Ausherman

A Quiet Eye—The Unique Achievement of Sylvia Shaw Judson, by Rowena Loverance

An Introduction to Minnie Jane Hardman, by Hannah Lyons

Helen Allingham’s Country Cottages: Subverting the Stereotype, by Amy Lim

Reflections on the Audacious Art Activist and Trailblazer Augusta Savage, by Sandy Rattley

Women Artists from Savannah at the Telfair Academy Museum, by Julie Allen

Science, Nature, and Music in the Art of Alma Thomas, by Erika Gaffney

The Cheerful Abstractions of Alma Thomas, by Alexandra Kiely

Illuminating Sarah Cole, by Kristen Marchetti

Defining Moments: Mary Cassatt and Helen McNicoll in 1913, by Julie Nash

Laura Seymour Hasbrouck, A Painter of the Hudson River School, by Lili Ott

Susie M. Barstow: Redefining the Hudson River School, by Nancy Siegel

The Rich and Complex Character of May Morris, Designer, Embroiderer, Jeweller and Writer, by Thomas Cooper

Marie Spartali Stillman’s The Last Sight of Fiammetta, by Margaretta S. Frederick

Evelyn De Morgan: Painting Truth and Beauty, by Sarah Hardy

Portraying May Alcott Nieriker, by Julia Dabbs

From a Project on Women Artists: The Calendar and the Cat Lady, by Lisa Kirch

Esther Pressoir: Imagining the Modern Woman, by Suzanne Scanlan

Are there any examples of her language usage in her poems and writing? Did she occasionally use the English Elizabethan language of Thee, Thy and Thou etc. around 1870 when she was about 64?

I have an autograph of her recommending a friend to use the Mrs. Winslow’s Receipt Book of 1870.

Her comment on the rear of the little 4 x 6 inch book says: Dear Friend,

I assure thee, this receipt book is what you need. I am the friend.

Signed

S. M. Douglass