Guest post by Howard Burton, author and documentary filmmaker

One of the great advantages in dedicating an entire film to one particular painting is that it gives you ample opportunity to take a lingering, comprehensive look at the surrounding historical context in all of its fascinating detail in order to make the most sense of what you’re seeing.

Sofonisba’s Chess Game

Our latest Renaissance Masterpieces film, on The Chess Game, painted by Sofonisba Anguissola (c. 1532/5–1625) in 1555, strives to do precisely that. From Sofonisba’s deliberate invocation of a decidedly Leonardesque blue-hilled background beyond a river, to the meticulously-crafted jewelry worn by two of the Anguissola sisters that are clearly displayed by their mother two years later in Sofonisba’s portrait of her, to the intricate, colored tablecloth underneath the chess board that makes an appearance in another Sofonisba portrait of an unknown sitter. Time and again we find ourselves thoroughly immersed in Sofonisba’s particular domestic and cultural world of mid-sixteenth-century Northern Italy.

Meanwhile, her decision to involve her characters in a game of chess might well be linked to the growing popularity of a celebrated pastime that Marco Girolamo Vida, the renowned humanist and Anguissola family friend who five years earlier had proudly singled out Sofonisba’s celebrated artistic abilities in his Latin oration Against the Pavians.

An Inspiring Role Model

Looked at sufficiently carefully, then, any great painting is much more than an isolated artistic accomplishment: it’s a chance to jump headlong into a fascinatingly intricate web of beliefs, values and influences.

But in Sofonisba’s case the contextual implications go even further than most, given her unique position as a universally-acknowledged master painter who was also female.

We’ll likely never be able to exactly assess the full extent of Sofonisba’s influence on other women painters, but even the little that we do know guarantees that her impact was considerable.

Irene di Spilembergo (1538–1559)

Legend has it that Sofonisba’s example so inspired Irene di Spilembergo, a highly accomplished poetess and musician, that she persuaded Titian, a family friend, to give her painting lessons. Unfortunately, none of her paintings survive, but her tragically short life was long eulogized as one representing the acme of female cultural accomplishment.

Fede Galizia (c. 1578–1630)

Fede Galizia, the deeply impressive painter and still life pioneer whose artistic abilities the celebrated artist and art theorist Gian Paolo Lomazzo touted when Fede was only 12 years old, was born in nearby Milan; her artist father Nunzio trained her. Sofonisba’s reputation would definitely have loomed large throughout both of their lives and likely played a significant role in the initial decision to have Fede follow in her father’s artistic footsteps.

Marietta Robusti (1560–1590)

Tintoretto’s daughter, Marietta Robusti—sometimes referred to as “Tintoretta”—must also surely have found inspiration in Sofonisba’s overpowering reputation as an eminent portraitist who consistently depicted herself wearing a simple black outfit unadorned with any jewelry.

Robusti’s biographer, Carlo Ridolfi (1594–1658), noting her unusual habit of dressing as a boy in order to move around the city sufficiently unhindered to study the surrounding art, effused that, “she will serve in the future as a model of womanly virtue, making known to the world that gems, gold, and precious clothing are not the true female adornments, but rather those virtues that shine in the soul and remain eternal after life.”

Lavinia Fontana (1552–1614)

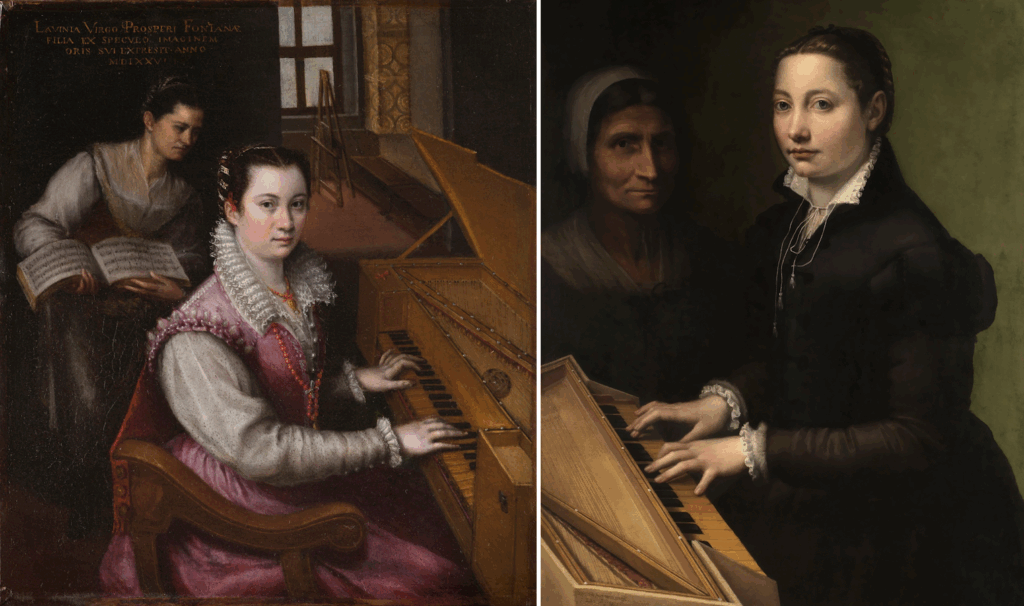

Then there’s Lavinia Fontana, another artist’s daughter. In her 1577 Self-Portrait at the Spinet, Fontana clearly eschews Sofonisba’s trademark basic sartorial style (unsurprisingly, given that she created it explicitly to impress her prospective father-in-law of her cultural sophistication and general suitability to marry his son) but there’s little question that the work is otherwise a straightforward tip of the hat to Sofonisba’s Self-Portrait at the Keyboard—complete with a maid in the background (the very same maid, in Sofonisba’s version, who makes an appearance in The Chess Game).

Right: Self-Portrait at the Spinet, 1561, by Sofonisba Anguissola; Spencer Collection, Althorp

Fontana went on to make another famous painting clearly inspired by Sofonisba, one for which we even have documentary evidence of the link between the two. In 1579, Alfonso Chacón, a Dominican scholar living in Rome, asked for her self-portrait, to use as a model for an engraving for his collection of 500 famous men and women where she would appear alongside Sofonisba.

Chacón’s collection of engravings never saw publication, as it happens. But we do have the portrait Fontana sent to him for the occasion—a magnificently revealing tondo which features the painter in her studio, thoughtfully contemplating her next work of art while looking straight out at us in a typically Sofonisba-like pose. The painting convincingly manifests a confident, rigorously acquired self-assurance—exactly like, we’re immediately prompted to think, the figure of Sofonisba’s sister Lucia in The Chess Game.

Sofonisba’s Sisters: Anna Maria, Europa and Lucia

Which brings me to the last, but no less significant, category of female painters that Sofonisba strongly influenced: her sisters.

For them, Sofonisba wasn’t merely an inspiringly successful role model, but also their teacher, particularly Lucia, who in turn, must have been the primary artistic trainer of both Europa (the smiling little girl in The Chess Game) and the Anguissola’s youngest child, Anna Maria, after Sofonisba left for Spain in 1559.

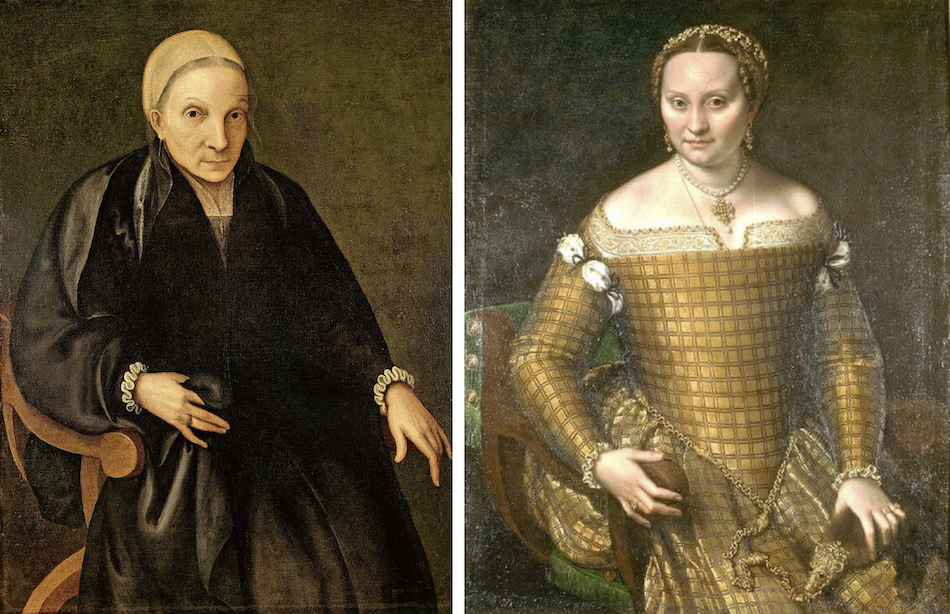

Recent analysis by the Columbia University Sofonisba specialist Michael Cole (see here for a related talk) has found that the painting of an old woman in Copenhagen’s Nivaagaards Malerisamling Museum, which scholars long believed to have been Sofonisba’s last self-portrait, was actually Europa’s work, a depiction of her mother-in-law. A careful examination of this painting reveals many strong similarities with Sofonisba’s 1557 portrait of their mother referred to above, from the position of the sitter’s hands to the type of chair.

Right: Portrait of Bianca Ponzone, 1557, by Sofonisba Anguissola; Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

Meanwhile Lucia herself was surely Sofonisba’s most talented student, an artist Filippo Baldinucci wrote might well have eclipsed Sofonisba had she not died in her 20s. Giorgio Vasari, who visited the Anguissola home in Cremona several years later, singled out her celebrated Portrait of Pietro Manna for praise. He wrote that, “Lucia, dying had left of herself no less fame than that of Sofonisba” through her paintings that “were no less beautiful and valuable than those by her sister.”

An Enduring Legacy

After several centuries of shameful near-anonymity, Sofonisba Anguissola is only now beginning, four hundred years after her death, to get the recognition she so richly deserves as one of the most compelling and insightful portraitists of her time. But the long-term cultural impact she generated through establishing herself as a female artistic icon might well have been considerably greater still.

Howard Burton is an author and documentary filmmaker. He holds a PhD in theoretical physics and an MA in philosophy and was the Founding Director of Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics. Howard has hosted and filmed over 100 conversations with world-leading researchers across the arts and sciences and produced 65 short documentaries plus 7 feature-length documentaries, including Through the Mirror of Chess: A Cultural Exploration and Sofonisba’s Chess Game.

More Art Herstory posts about Sofonisba Anguissola

Sofonisba Anguissola: Portraitist of the Renaissance at Rijksmuseum Twenthe, by Nelleke de Vries

Renaissance Women Painting Themselves, by Katherine McIver

A Tale of Two Women Painters, by Natasha Moura

Sofonisba Anguissola in Enschede, an Exhibition Review, by Erika Gaffney with Cara Verona Viglucci

Art Herstory’s Sofonisba Anguissola resource page

More Art Herstory posts about Italian women artists

Plautilla Bricci (1616–1705): A Talented Woman Architect in Baroque Rome, by Dr. Consuelo Lollobrigida

Female Solidarity in Paintings of Judith and her Maidservant by Italian Women Artists, by Sivan Maoz

Plautilla Nelli and the Restoration of her Altarpiece Madonna del Rosario. by Jane Adams

Lavinia Fontana: Italy’s First Female Professional Artist, by Elizabeth Lev

Elisabetta Sirani of Bologna (1638–1665), by Adelina Modesti

Suor Orsola Maddalena Caccia (1596–1676), Convent Artist, by Angela Ghirardi

Giovanna Garzoni’s Portrait of Zaga Christ (Ṣägga Krǝstos), by Alexandra Letvin

Two of a Kind: Giovanna Garzoni and Artemisia Gentileschi, by Mary D. Garrard

Renaissance Women Painting Themselves, by Katherine McIver

Sister Eufrasia Burlamacchi (Lucca, 1478–1548), by Loretta Vandi

Sister Caterina Vigri (St. Catherine of Bologna) and “Drawing for Devotion,” by Kathleen G. Arthur

The Priceless Legacy of Artemisia Gentileschi: A Curator’s Perspective, by Judith W. Mann

Trackbacks/Pingbacks