Guest post by Alice M. Rudy Price, independent scholar

Danish audiences celebrate the Danish painter Anna Brøndum Ancher (1859–1935) for her vibrant color sense, images filled with sunlight, and her depictions of traditional life in rural and coastal Denmark during the Modern Breakthrough, a period of heightened naturalism with a focus on contemporary life.

Anna’s Early Artistic Career

Her family inn in Skagen, at the tip of the Jutland Peninsula, hosted an important artist colony at the end of the nineteenth century, and Ancher was one of the few affiliated women painters who gained a national reputation. In the twenty-first century she has been the focus of monographs and exhibitions in Denmark, as well as in Washington, DC. At the 1889 Exposition Universelle she earned a silver medal for Maid in the Kitchen (Figure 2). Sunlight in the Blue Room (1891) is one of her most beloved and frequently exhibited paintings (Figure 3).

Ancher, like sculptors Harriet Hosmer and Anne-Marie Carl Nielsen, hesitated to embroil herself in women’s activism or to engage in activities that could encourage gender-based marginalization. As a young artist, she withdrew her name from colleague Johanne Krebs’s petition for better art training for women, and she kept out of public debates until the 1910s. However, at the turn of the century, her paintings begin to tackle major civic issues, especially those raised by the women’s movement. By the time the Kvindelige Kunstneres Samfund (Women’s Art Society) launched in 1916, Ancher was a pivotal figure.

A Painting at a Pivotal Moment

Anna Ancher’s Vaccination (1899; Figure 1) transforms a public-school room into feminine space where attentive women nurture their robust children by attaining inoculations and by breastfeeding. The depiction corresponds to the year that Danish married women earned the designation as “majority,” competent to manage their own legal affairs, with limited property rights, but without custodianship over the same children whose care they provide. Ancher’s subject selection tackles a significant public health issue from a gendered perspective at a pivotal moment in Danish women’s history.

Mette Bøgh Jensen has appropriately situated Vaccination within the context of medical imagery of the nineteenth century. Compulsory smallpox vaccination was enacted in Denmark in 1810 and Bøgh Jensen finds that in depicting such scenes, the work departs from contemporary Danish art. However, Ancher’s painting coincides with a growing international, mostly female movement resisting vaccination. Ancher completed the painting the year after Britain legalized conscientious objection to mandatory inoculations, an act that Nadja Durbach argues drew the most support from working-class women. Concurrently, petitioners in Germany pursued conscience clauses. Ancher’s painting not only affirms vaccination as a healthy, hygienic practice, but also couples the practice with a favorable depiction of breastfeeding.

The Larger Context: Women and Social Policy

At the turn of the century, the international women’s movement advocated for “home economics,” and for measures that would improve children’s wellbeing through household hygiene and efficiency using applied science and instruction. In her widely translated Century of the Child (1900), Swedish feminist Ellen Key, depicted by Swedish painter Hanna Hirsch-Pauli in Figure 4, advocated for a period of training in “the care of children, hygiene, and sick nursing” that was as long and as rigorous as the military training of Swedish males.

The Danish Women’s Society featured Key as the lecturer at the important Women’s Exhibition of 1895 in Copenhagen. At the time Ancher was making studies for Vaccination, the Society organized household schools, especially targeting poor families. The International Congress of Women also indicated in their 1900 conference proceedings that the Danish parliament explored hiring female managers for the protection of infancy and the administration of the poor relief fund.

Home economics programs that encouraged rationalized meal preparation and bathing practices were embraced by international women’s meetings. In 1899, Danish delegate Johanne Ottosen addressed the London congress to urge that a regimen of bathing and maintaining a clean home would lead to strong and healthy children. The perceived importance of good diet and exercise motivated Danish women to form and encourage membership in their own Health Society. Its primary focus was to teach best practices for raising salubrious children. American advertisers capitalized on the movement. Procter & Gamble focused on children’s skin and nursery settings through text and image in promoting Ivory Soap in illustrations by Alice Barber Stephens (Figure 5) and Jessie Willcox Smith (Figure 6).

The Healthy Child

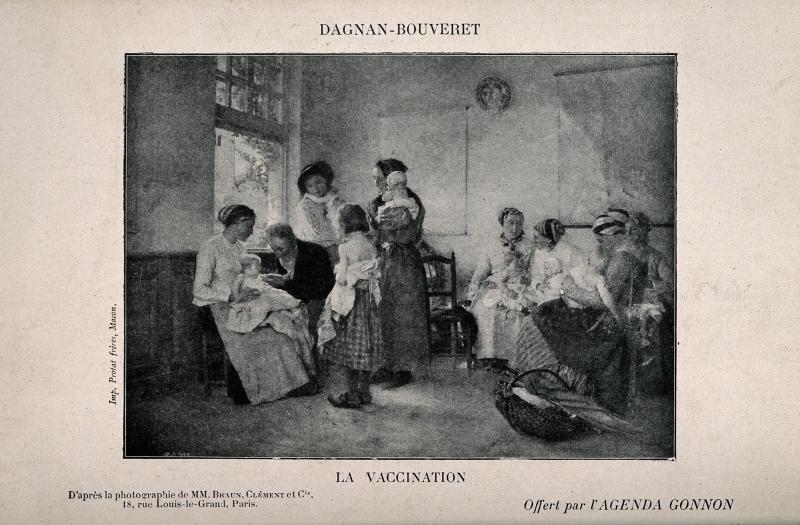

Ancher’s Vaccination affirms physician-endorsed practices and the preoccupation with cleanliness. The depicted immunization event takes place in a sterile room with large windows letting in natural light and a view of the outdoors, suggestive of fresh air. The children’s arms have a touch of blood, but no inflammation. The process is orderly and hygienic. Ancher’s handling contrasts with older comparable paintings from France, such as Vaccination (1879) by Pascal Adolphe Dagnan-Bouveret (Figure 7), exhibited to great acclaim at the Exposition Universelle in 1889 and frequently mentioned and reproduced in the contemporary press.

Dagnan-Bouveret’s painting coincides with earlier debates over compulsory vaccination in Germany. Malte Thießen indicates that concerns about class inequity fueled these debates; the wealthy, propertied classes may have had access to private vaccinations, but the “‘working classes” had to make do with free but “unhygienic mass vaccinations,” perhaps held in factories with children as the guinea pigs in medical experiments.

Class was also a factor in the public reception of Ancher’s painting. Bøgh Jensen quotes a contemporary critic describing the scene as “a doctor vaccinating (screaming) local fishermen’s children.” The deprecating reference to “fishermen’s children” signaled a presumed distance between the contemporary viewer of modern art and the depicted subject.

The Women’s Movement and Children’s Welfare

Bøgh Jensen appropriately compares Ancher’s painting to Emilie Mundt’s From the Orphanage in Istedgade, 1886 (Figure 8) to emphasize that the artists’ depiction of children as subjects demonstrated a shared conviction that public health efforts focused on young people’s physical health, which would, in turn, benefit future generations of Danish citizens. This comparison ties Ancher’s motifs directly to the concerns of the women’s movement. Mundt and her partner Marie Luplau, also an artist, were extremely active in the women’s movement. They featured on the front page of the Women’s Association newsletter in 1891, where Mundt’s “asylum pictures” received high praise.

In addition to depicting rosy-cheeked, fair-haired children in the bright, well-ventilated clinical setting, Ancher prominently positions three young women breastfeeding, another home economics reform linked to scientific motherhood. Ancher’s compositional placement (Figure 9) claims for the nursing mothers the position where Dagnan-Bouveret had placed idle, seated women holding children in their lap. Several aspects of this arrangement are worth noting: modern women seem to be caring for their own children in a semi-public setting, the activity of breastfeeding is normalized, and the depiction is by a professional woman who enjoyed elevated status in the community.

The artist’s viewpoint is authoritative and yet inobtrusive. Inoculation and breastfeeding are juxtaposed as examples of healthy childrearing—without any hint of eroticization or fantasy, contrary to the well-known examples in French literature and art of the nineteenth century identified by Lisa Algazi Marcus in her 2022 book, Realism, Naturalism, and the Eroticization of Breast-Feeding. Ancher’s grouping of the doctor, child, and mother are more precisely rendered than the mothers nursing their children. Nonetheless, Ancher overlays the light blue of the wall above their heads with a golden orange that encourages the viewer to notice, but not to fixate on, mothers who breastfeed.

Scientific Motherhood and Modernity

Ancher consistently uses elements of dress to signal the extent to which her subjects identified with modernity. She depicted religious women of Skagen’s Inner Mission (Figure 10) and regional working fisherwomen in traditional headscarves. In the final version of Vaccination, she eliminated older women and those with traditional dress.

Although seemingly from laboring families in the rural Skagen region, they are more modern than the peasants depicted by Dagnan-Bouveret. Establishing their modernity aligns Ancher with the attitudes of the Danish women’s movement rather than deferring to French expectations. In 1890, Denmark’s women’s rights newsletter promoted granting working women leave while they were “serving” their children by breastfeeding, thereby preventing children from becoming “sick and poorly.”

Ancher blends breastfeeding mothers into the composition rather than exhibiting them at the forefront as exceptional. The very ordinariness of the scene communicates breastfeeding as a common practice for Skagen’s young mothers. Scientists and physicians also increasingly encouraged breastfeeding. Gunnar Thorvaldsen discusses contemporary medical research opinions encouraging breastfeeding as more sanitary with the potential to reduce high infant mortality rates caused by diarrhea attributed to contaminated milk. Danish handbooks on infant care commonly recommended breastfeeding for at least a few months. In Century of the Child, Key emphasized the importance of breastfeeding for the first six months of life, citing English research.

Ancher, like her Finnish colleague Elin Danielson-Gambogi in the 1893 painting Mother (Figure 11), illustrates young babies correctly positioned with minimal painterly attention to the flesh or form of the breast. Although Danielson-Gambogi depicts nursing within a bourgeois bedroom, Ancher shows working mothers breastfeeding their children in a public, civic setting. The Vaccination displays a civic space occupied by women according to the female gaze. The only male is the physician giving the injections (for which Ancher’s husband modeled). Ancher paints at a moment of rising nationalism, and throughout Europe, increasing government controls over the family and concerns about decreasing birthrates.

Conclusion

Examining Ancher’s shift in painting subjects at the turn of the century in the context of the evolving women’s movement introduces necessary complexity to her evolving career as an artist. When she made her debut, Ancher resisted controversy and activism related to women’s rights. Her attitude toward the movement was dynamic, however. In 1895, she exhibited in Copenhagen’s important Women’s Exhibition of decorative and fine arts that both marked the accomplishments of women and paved the way for the formation of the Danish Women’s Art Association and the construction of a permanent Women’s Building (Figure 12) in Copenhagen.

The Danish Women’s Art Association claims that Ancher “…ended up actively supporting” its establishment in 1916 and became in the following years its most famous public member, a “prominent voice in the debate of the time about the inequality between men and women in the art world.” Vaccination suggests that by 1900 Ancher was already thoughtfully engaged with the issues raised by more outspoken activists.

Alice M. Rudy Price received a Ph.D. in art history from Temple University, Tyler School of Art and Architecture. Her dissertation on the Danish artist Anna Ancher (1859–1935) addressed the artist in relation to the intersecting cultural contexts of rural Denmark, the Skagen Art Colony, Copenhagen and Paris. Loss, the Female Nude and Anna Ancher’s Grief: A Woman’s Own Modernism considered Ancher’s Grief (1902) in light of the issues it raises about the maternal body, nakedness and grief. Her larger research project considers the visibility and invisibility of the aging woman’s body in modernist discourse. She is co-editor with Emily C. Burns of Mapping Impressionist Painting in a Transnational Context. An adjunct instructor, Dr. Price teaches art history at Tyler and architecture history at Jefferson University, College of Architecture and the Built Environment. Price also holds Masters degrees in education and history.

More Art Herstory guest posts by Alice M. Rudy Price:

Modern Women Artists in Copenhagen 2024–2025: Three Exhibitions

Marie Laurencin: Sapphic Paris, A Review

Other Art Herstory blog posts you might enjoy:

Nancy Sharp: An Undeservedly Forgotten Exemplar of Modern British Painting, by Christopher Fauske

Marie Laurencin: Sapphic Paris, A Review, by Alice M. Rudy Price

The Rich and Complex Character of May Morris, Designer, Embroiderer, Jeweller and Writer, by Thomas Cooper

Anna Boberg: Artist, Wife, Polar Explorer, by Isabelle Gapp

Marie Laurencin and the Autonomy of Self-Representation, by Mary Creed

Evelyn De Morgan: Painting Truth and Beauty, by Sarah Hardy

Dalla Husband’s Contribution to Atelier 17, by Silvano Levy

Happy Birthday, Fidelia Bridges! by Katherine Manthorne

Esther Pressoir: Imagining the Modern Woman, by Suzanne Scanlan

The Ongoing Revival of Matilda Browne, American Impressionist, by Alexandra Kiely

The Theatrical Wonders of Jeanne Paquin’s Belle Époque Parisienne, by Julia Westerman

Eunice Golden: Making Space for Female Eroticism in the Art Institution, by Isabel Gilmour

From a Project on Women Artists: The Calendar and the Cat Lady, by Lisa Kirch

The Life and Art of Dorothea Tanning, by Victoria Carruthers

The Abstract-Impressionism of Berthe Morisot and Joan Mitchell, by novelist Paula Butterfield

Victorine Meurent, More than a Model, by novelist Drēma Drudge

Trackbacks/Pingbacks