Guest post by Alexandra Letvin, Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College

A Black man looks out from an ultramarine blue background. His hair is grown out, and he wears a red jacket adorned with gold braids and a lace collar. The precision with which the man’s features and clothing are rendered belie the miniscule size of this captivating image: it measures a mere 2-1/4 by 1-7/8 inches.

Made in 1635, this is the earliest known European portrait miniature to depict a Black sitter. Beyond this historical “first,” it is a fascinating document of an encounter at an early modern European court between two people whose identities marked them as “outsiders”: the Ethiopian traveler Zaga Christ (Ṣägga Krǝstos) (c. 1616–1638) and the Italian woman artist Giovanna Garzoni (1600–1670).

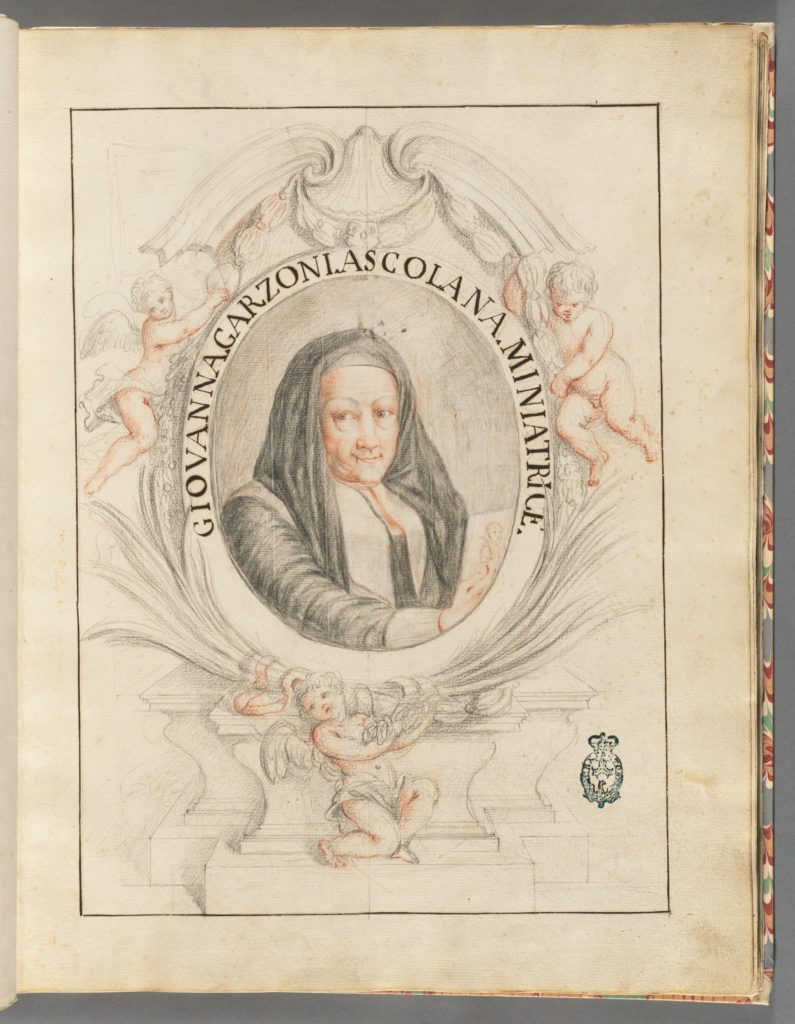

Giovanna Garzoni

The general contours of Garzoni’s life and career are likely well known to readers of Art Herstory, thanks to the landmark 2020 exhibition “The Greatness of the Universe” in the art of Giovanna Garzoni curated by Sheila Barker at the Uffizi, and to blog posts by Mary D. Garrard and Emma Steinkraus.

Born in Ascoli Piceno, Garzoni was among the most successful women artists of her generation. In a profession dominated by men, she navigated the court networks and scientific circles of the Italian peninsula and even traveled farther afield to England and France.

Garzoni’s production encompassed an impressive range of media and genres, from calligraphy to textiles to still lifes. As the Uffizi exhibition demonstrated, her still lifes in particular reveal her “geographical imaginary” in their inventive combinations of Asian porcelain, exotic seashells, and botanical specimens.

Garzoni produced many of these still lifes during and after her second stay at the Medici court in Florence, where she worked between 1642 and 1651. There she had first-hand access to the vast Medici collections of treasures from around the globe. Years earlier, however, we see evidence of her curiosity and engagement with the world beyond Europe in her miniature of the Ethiopian traveler Zaga Christ.

A Disenfranchised Prince

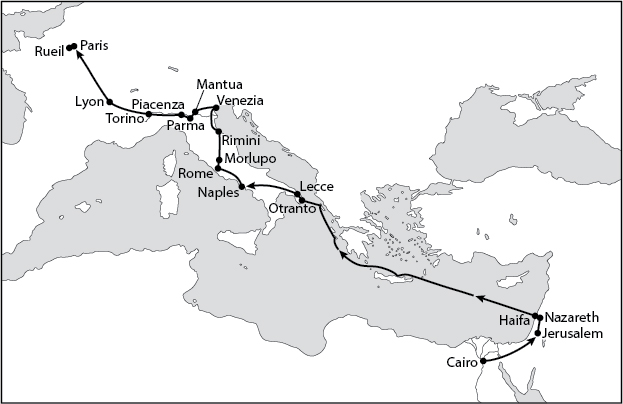

By the time Garzoni met Zaga Christ in 1634 at the court of the Duke of Savoy in Turin, he had traveled across several continents, skillfully negotiating the expectations and cultural norms of the Europeans he encountered along his way.

Zaga Christ first appears in the historical record in 1632, when he arrived at the Venetian consulate in Cairo claiming to be the rightful heir to the throne of the Christian Kingdom of Ethiopia. He recounted a harrowing flight from Ethiopia after Emperor Susenyos (r. 1607–1632) killed his father, Emperor Yaqob I (r. 1597–1603; 1605–1607). While riddled with chronological inaccuracies, his story intrigued Paolo da Lodi, the consulate’s chaplain and prefect of the Franciscan mission in Egypt. He spotted in this dispossessed royal a unique opportunity to increase Franciscan influence in Ethiopia at a time when the rival Jesuit presence there was waning.

With Father Paolo’s help, Zaga Christ traveled to Jerusalem. He converted to Catholicism in Nazareth and in fall 1632 boarded a Venetian boat bound for Rome, embarking upon an extraordinarily well documented journey from southern Italy to northern France that Matteo Salvadore has recently detailed.

An Ethiopian in Europe

Ethiopia had long held a prominent place in the European Christian imagination. The Kingdom’s rulers had adopted Christianity in the 4th century, and delegations of Ethiopians came to Europe in increasing numbers beginning in the 1300s, seeking to forge pan-Christian alliances against the Ottoman Empire. By the late 1400s, the number of Ethiopians visiting Rome was so great that a center for Ethiopian pilgrims was established at Santo Stefano Maggiore (subsequently known as Santo Stefano degli Abissini).

Many of the Europeans that Zaga Christ met during his travels were particularly excited by his story because of the resonances between his proclaimed identity and the medieval legend of Prester John, a powerful Christian ruler whose realm beyond the Muslim world was initially located ambiguously in Asia or Africa, but who came to be associated with Ethiopia in the 14th century. Some sought to help Zaga Christ return to Ethiopia to reclaim the throne and promote Catholicism (a particularly pressing concern amidst rising anti-Catholic sentiment there). Others were suspicious of his story and questioned if he was truly who he claimed to be.

An Encounter at Court

Accompanied by four Franciscans charged with escorting him back to Ethiopia, Zaga Christ left Rome in 1634 for Venice. After a series of illnesses, he spent the winter of 1634–35 recuperating in Turin at the court of the Duke of Savoy, where he met Giovanna Garzoni.

Garzoni’s career had taken her to Florence, Venice, Naples, and Rome before Christine of France, Duchess of Savoy, requested her services in 1632. Her official title was “La Miniatrice di Madama Reale” (miniaturist to the Duchess). But Garzoni appears to have executed a range of works in Turin beyond miniature portraits, including still lifes and religious, mythological, and allegorical scenes.

Portraiture was nonetheless central to Garzoni’s work at court. Offering a means of self-fashioning, documenting accomplishments, asserting dynasties, and cementing relationships, portraiture had long been at the center of European courtly artistic production. Garzoni executed portraits not only of living figures such as the Duke of Savoy, but also of his deceased ancestors—and she likely made many more whose current locations are unknown.

The Miniature

Sometime in the winter of 1635, Garzoni rendered Zaga Christ’s likeness. Her miniature captures his appearance with breathtaking sensitivity and empathy.

Garzoni’s portrait departs significantly from typical early modern European depictions of Black people. Many of the earliest European images of Black figures appear in scenes of the Adoration of the Magi.

Another common formulation was to show a wealthy white aristocrat with an enslaved Black person looking up at them adoringly.

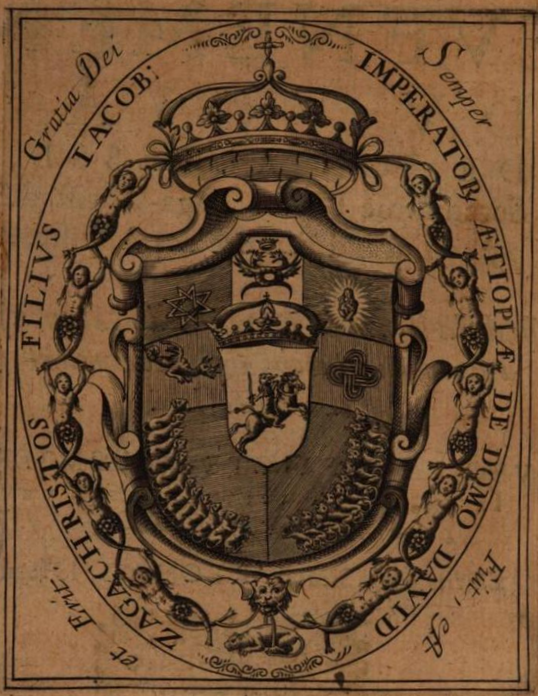

But there are few instances of Black sitters depicted as individualized people rather than generic types. This is evident in two printed images of Zaga Christ from the 17th century, which show him in an exoticized fashion, with a large turban on his head and exaggerated facial features.

Garzoni, in contrast, takes great care to record Zaga Christ’s likeness. Her close observation and exacting technique offer a delicate representation of the man historian Maiolino Bisaccioni described in 1634 as “19 or 20 years old, of a color between black and olive [di colore tra’l nero, e l’olivastro], of very beautiful appearance [bello aspetto], with sparse facial hair, with very black and curly hair, and of medium height … very devout, affable, majestic, and melancholic.”

The miniature’s reverse, however, is as intriguing as its obverse. It is signed not once, but twice. At the bottom, Garzoni’s Italian name appears in a Latin script; above, it is transliterated into the Ethiopian language Amharic.

Scholars of Amharic have noted that the letters are poorly formed, suggesting that it was written by someone unfamiliar with the language, most likely Garzoni herself. If that’s the case, it is a remarkable testament to the relationship between artist and sitter, and to the artist’s curiosity and interest in the sitter.

Original or Copy?

Soon after the miniature was completed, Garzoni and Zaga Christ went their separate ways. Following the Duke of Savoy’s death in 1637, Garzoni left Turin and traveled on to England, France, Rome, and Florence.

Zaga Christ departed Turin earlier, in 1635. He went to France, where he ingratiated himself with Cardinal Richelieu and King Louis XIII. In 1637, he was arrested under suspicion of adultery; he died in 1638 at Richelieu’s residence in Rueil. His gravestone (now destroyed) read:

Here lies the king of Ethiopia

The original, or the copy:

Was he king? Was he not?

Death has finished the discussion.

This epitaph underscores the questions regarding Zaga Christ’s identity—whether he was truly an Ethiopian prince, and whether his conversion to Catholicism was genuine—that dominated discourses about him both during his lifetime and in the centuries following his death. While many of his contemporaries were unwilling to make a final determination, historians have since accepted that he was an impostor.

But this should not distract us from acknowledging Zaga Christ as expertly attuned to the geopolitical and religious outlooks and interests of his European hosts—and as ready to capitalize on them to advance his own position. In this, we might speculate that Garzoni recognized in Zaga Christ something of a kindred spirit: someone whose savvy self-fashioning and self-promotion allowed him to open doors typically closed to “outsiders” of elite European networks.

“Memorable and Illustrious Things of Your Museum”

The fate of Garzoni’s miniature following its creation is not known, but it was documented in two French collections in the 18th century. It first appears with the banker Jean Cottin (1680–1745). At the 1752 sale of his collection, Pierre-Charles-Alexandre Helle purchased the miniature for Gilbert Paignon-Dijonval (1708–1792), secretary to King Louis XVIII. This early provenance suggests that Zaga Christ may have commissioned the portrait to bring with him to the French court as a gift.

Indeed, Zaga Christ clearly understood the power and appeal of his own (fabricated) identity. This is perhaps most evident in his decision to write, copy, and distribute a 5,000-word autobiographical statement to European contacts. When sending it to Francesco Gualdo, secret chamberlain of Pope Urban VIII and well known for his cabinet of curiosities, he tellingly remarked that it could be added to the “other memorable and illustrious things of your museum [museo].”

Zaga Christ’s likeness rendered in miniature by Garzoni may have functioned as yet another “collectible” for Europeans. But the miniature—and the cross-cultural encounter it encapsulates—also invites us to consider anew themes of cultural negotiation, foreignness, and belonging in early modern Europe.

Dr. Alexandra Letvin is the Assistant Curator of European and American Art at the Allen Memorial Art Museum (AMAM), Oberlin College, where she oversees a collection of approximately 5,500 paintings, sculptures, and works on paper before 1900. Garzoni’s Portrait of Zaga Christ, recently acquired by the AMAM, is the focal point of Letvin’s installation Mobility and Exchange, 1600–1800, on view through August 14, 2022.

Visit Art Herstory’s Giovanna Garzoni resource page, here.

More Art Herstory blog posts about Giovanna Garzoni:

“La grandezza del universo” nell’arte di Giovanna Garzoni / “The grandeur of the universe” in the art of Giovanna Garzoni, by Sara Matthews-Grieco

Two of a Kind: Giovanna Garzoni and Artemisia Gentileschi, by Mary D. Garrard

The Protofeminist Insects of Giovanna Garzoni and Maria Sibylla Merian, by Emma Steinkraus

As of November 2020, Art Herstory offers a Giovanna Garzoni note card! Visit the shop for details.See also the Art Herstory Giovanna Garzoni resource page.

More Art Herstory blog posts about 17th-century Italian women artists:

Three Historic Women Artists Exhibitions: A Dispatch from Italy, by Alessandra Masu

Plautilla Nelli and the Restoration of her Altarpiece Madonna del Rosario. by Jane Adams

Roma Pittrice: Women Artists at Work in Rome Between the Sixteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, by Alessandra Masu

Maddalena Corvina’s Saint Catherine of Alexandria, by Kali Schliewenz

Judith’s Challenge, from Lavinia Fontana to Artemisia Gentileschi, by Alessandra Masu

Thoughts on By Her Hand, the Hartford Iteration, by Erika Gaffney

Plautilla Bricci: A Painter & “Architettrice” in Seventeenth-century Rome, by Alessandra Masu

Thoughts on Feminist Art History in the Wake of Artemisia: Vrouw & Macht at Rijksmuseum Twenthe, by Dr. Jitske Jasperse

By Her Hand: Personal Thoughts and Reflections on an Exhibition, by Oliver Tostmann

In defense of monographic exhibitions of female artists: The case of Fede Galizia, by Camille Nouhant

The Ladies of Art are in Milan, by Cecilia Gamberini

“Artemisia” at the National Gallery: A Review, by Sheila McTighe

Artemisia Gentileschi: What Wasn’t in the London Exhibition and Why it Matters, by Jesse Locker

Plautilla Bricci (1616–1705): A Talented Woman Architect in Baroque Rome, by Consuelo Lollobrigida

Orsola Maddalena Caccia (1596–1676), Convent Artist, by Angela Ghirardi

The Priceless Legacy of Artemisia Gentileschi: A Curator’s Perspective, by Judith W. Mann