Guest post by Mary Creed

In an attempt to tell a more inclusive story of modern art, New York City’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) recently initiated a rehang of its permanent collection to include the contributions of historically underrepresented, marginalized artists. MoMA has also rethought hierarchies of mediums–which had traditionally held painting at the pinnacle—by exhibiting more photographs, objects of design, and works on paper.

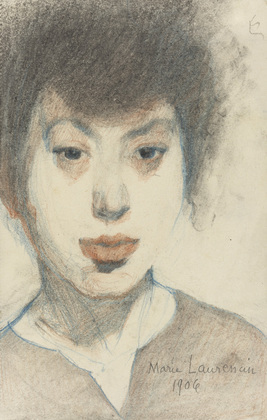

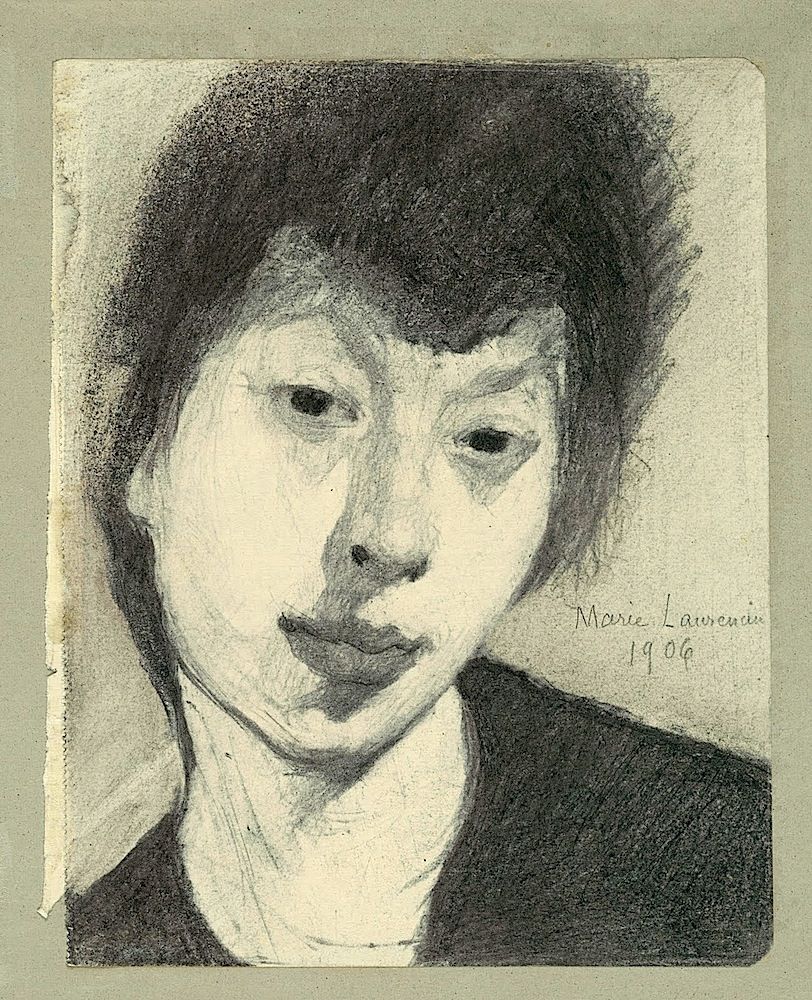

As part of this effort, MoMA now displays two self-portraits by the French artist Marie Laurencin (1883–1956) (Figs. 1, 2). Throughout history, self-portraiture has been practiced by women artists as a mode of self-promotion. It gave women the opportunity to portray themselves as they wished to be seen and to control their own public image.

The two Laurencin self-portraits are taken from her sketchbooks and are drawn in pencil, one with the addition of colored pencil. Both are signed and dated 1906, and are characteristic of an early period of her work in which she worked in a more naturalistic manner. Her approach would become increasingly more stylized throughout her lifelong career as an artist.

Paris Avant-Garde” in the exhibition “Collection 1880s–1940s” October 30, 2021–ongoing. IN2477.503.1. Photograph by Robert Gerhardt. Museum of Modern Art, New York

The two works appear together in a gallery rotation presently titled “Picasso, Rousseau, and the Paris Avant-Garde,” dedicated to the origins of Cubism (Fig. 3). Laurencin’s work was informed by Cubism but developed into a unique style that blended the sensuality of 18th-century Rococo with modernist ideas of perspective and subject matter. She never labeled herself as a Cubist, but she exhibited with them in several important exhibitions.

Laurencin’s self-portraits hang to the left of Picasso’s famed Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, engaging in a fierce stand-off between modes of representation. Within this juxtaposition lies a subtle and complex story of confrontation, subversion, and wit.

Laurencin in Picasso’s Women of Avignon

Laurencin met Picasso in 1907, the same year he completed Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (Fig. 4). The painting shocked the public through its unconventional proto-cubist style and its brazen subject matter of a modern-day brothel. At the time, a rumor circulated that Picasso had based the crouching figure in the lower right of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon after Laurencin. Picasso was likely influenced by the novel Les Onze Milles Verges (1907) by Guillaume Apollinaire (1880–1918). In the text, Apollinaire crudely described a sex worker, dismembered in an explosion, as in an “open book” position. Because Apollinaire and Laurencin were involved in a tumultuous romantic affair at the time, the character has been interpreted as a thinly veiled allusion to Laurencin.

Picasso in Laurencin’s Friends of Apollinaire

Art historian Julia Fagan-King has suggested that in response to Picasso’s violent depiction of her, Laurencin cleverly reclaimed ownership over her image through self-portraiture in her 1909 painting Apollinaire and his Friends (Fig. 5). In this group portrait, Apollinaire is seated at the center, and at the lower right, Laurencin is depicted in a position that recalls the crouching figure Picasso apparently based on her. Unlike the figure in Picasso’s painting, Laurencin is seated at a piano, confidently addressing the viewer in a decidedly less vulgar pose. She dons a conservative blue dress that covers her flesh, yet the sensuous contours of her leg remain visible. Rather than rejecting female sexuality, Laurencin asserts autonomy over her body and reframes her sexuality as her own.

To the left, Laurencin includes her patron Gertrude Stein in profile next to Fernande Olivier, Picasso’s girlfriend who was also rumored to be the basis for one of Picasso’s figures in Les Demoiselles d’Avingnon, and an unidentified woman. The figure group on the far right depicts the poets Maurice Cremnitz and Marguerite Gillot next to Picasso. Laurencin painted Picasso’s portrait in the very style that he employed in the figures in Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. Notably, it is the stylized eyes, nose, and mouth that most resemble Picasso’s technique (Fig. 7).

Based on the visual similarities, it appears Laurencin was conscious of Picasso’s assertion that the crouching figure in Les Demoiselles d’Avignon represented her. In what might have been mistaken as an homage, Laurencin appears subversively to poke fun at Picasso’s self-aggrandizement.

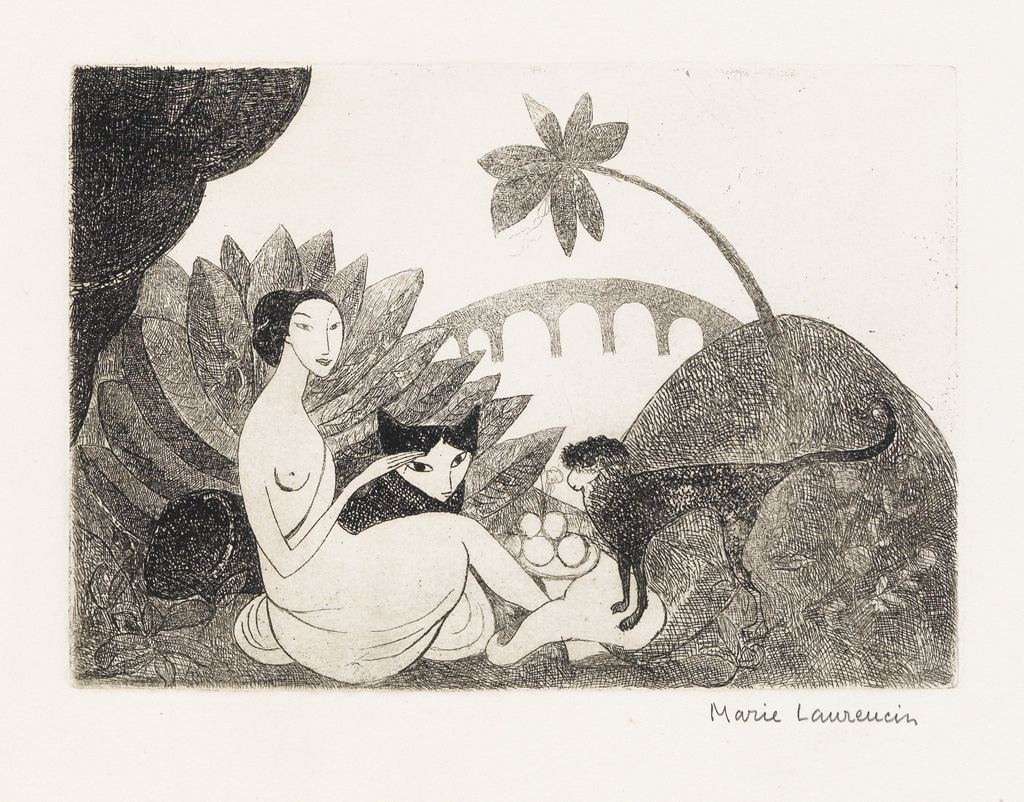

Laurencin and Meurent: Historical Misconstructions of Queerness and Sex Work

Apollinaire and his Friends was not the first work in which Laurencin appeared to parody a masterpiece of so-called male genius. Fagen-King has also argued that Laurencin’s etching Le Pont de Passy is a response to Manet’s Luncheon on the Grass (Figs. 8, 9). In Laurencin’s version, she inserted herself in place of Manet’s central model Victorine Meurent (1844–1927), and the male figures are humorously replaced with a cat and monkey.

A number of intriguing parallels exist between the lives and subsequent histories of Laurencin and Meurent. Meurent is recognized today as the model in Luncheon on the Grass and Olympia, but she was also an artist in her own right who exhibited her paintings at the Paris Salon.

She exhibited a self-portrait at the Paris Salon (Fig. 10). In the portrait, recently acquired by the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, she regards the viewer with cool indifference. Similarly, Laurencin’s work has (until recently) been considered secondary to her role as the literary muse of Apollinare. As muses, they were considered passive objects of inspiration, and their artistic endeavors were taken less seriously.

This label of muse to male creatives has also contributed to the erasure of Meurent and Laurencin’s queer identities. Laurencin had a complicated affair with Apollinaire, but she also had multiple significant romantic relationships with women. Toward the end of her life Laurencin legally adopted her partner Suzanne Moreau-Laurencin—a common practice between queer couples at the time to ensure legal rights to their partners that would not otherwise be recognized. Like Laurencin, Meurent lived with her partner Marie DuFour for two decades until her death.

Because several of Manet’s paintings of Meurent alluded to modern sex work, she has often been incorrectly referred to as a sex worker. It sheds light on this misconception to consider Meurent’s queerness in socio-historical terms. Lesbianism was often considered to be a vice common to sex workers in the early twentieth century. Literary and visual tropes of the “fallen woman” flourished at this time that linked sex work, lesbianism, and the risk of venereal disease as moral and physical threats to society. The danger of the modern woman is a central theme of Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, and his treatment of Laurencin may have been intended as a critical judgment on Laurencin’s sexuality.

Laurencin’s cheekily transgressive self-portrait as Meurent as a sex worker in Le Pont de Passy may have been one of her first tactical responses to Picasso’s depiction of her in Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. Laurencin likely identified with Meurent’s complex role as a queer artist and muse, and the criticisms she faced as a result.

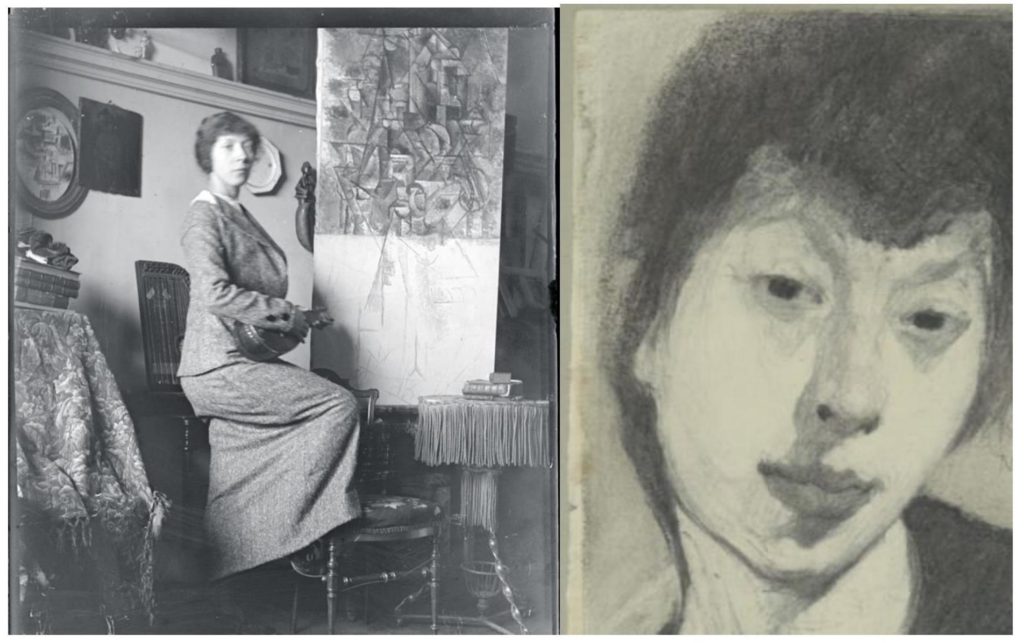

A Face-Off at MoMA

Laurencin’s irreverent parodies of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon and Luncheon on the Grass were resolute interventions to reclaim her image that she achieved through self-portraiture. She played with the seriousness of modernism. In a photograph taken in Picasso’s studio, she poses with a guitar in a tongue-in-cheek manner next to a Cubist portrait (Fig. 11). Laurencin used self-portraiture to negotiate her identity as a queer, mixed-heritage woman artist, and to occupy space among the male-dominated avant-garde in Paris. In a manner that blended wit with criticism, she recast the typical subjective relationship of artist and model and pushed back at the unhelpful and often harmful label of muse.

MoMA has conventionally exhibited Les Demoiselles d’Avignon alongside other historically considered giants of Cubism such as Braque and Gris. But now, Picasso’s painted vision of Laurencin is counter-balanced with her own self-image on the adjoining wall. Although her image is humbly drawn on the pages of a spiral notebook, in this confrontation, Laurencin holds her own.

Mary Creed earned her master’s degree in Art History with a concentration in Museum Studies at the City College of New York. She specializes in women and LGBTQIA artists who have been historically under- or misrepresented, such as Marie Laurencin, Elisabeth Jerichau-Baumann, and Romaine Brooks. She has completed research internships at The Metropolitan Museum of Art and The Barnes Foundation.

Other Art Herstory blog posts you might enjoy:

Blanche Hoschedé-Monet: An Artist in Her Own Right, by Rebekah Hoke Brown

Unpacking the Exhibition: Blanche Hoschedé-Monet in the Light, by Haley S. Pierce

An Introduction to Minnie Jane Hardman, by Hannah Lyons

Louise Moillon: A pioneering painter of still life, by Lesley Stevenson

Helen Allingham’s Country Cottages: Subverting the Stereotype, by Amy Lim

Marie Laurencin: Sapphic Paris, A Review, by Alice M. Rudy Price

The Rich and Complex Character of May Morris, Designer, Embroiderer, Jeweller and Writer, by Thomas Cooper

Marie Spartali Stillman’s The Last Sight of Fiammetta, by Margaretta S. Frederick

Visual Feasts: The Art of Sarah Mapps Douglass, by Erika Piola

Evelyn De Morgan: Painting Truth and Beauty, by Sarah Hardy

Anna Ancher’s Vaccination and Scientific Motherhood, by Alice Price

Celebrating Eliza Pratt Greatorex, an Irish-American Artist, by Katherine Manthorne

Victorine Meurent, More than a Model, by Drēma Drudge

The Many Faces of Suzanne Valadon, by Suzanne Singletary

Esther Pressoir: Imagining the Modern Woman, by Suzanne Scanlan

Madeleine Françoise Basseporte’s Hyacinths at the French Court, by Mary Creed

The Abstract-Impressionism of Berthe Morisot and Joan Mitchell, a guest post by novelist Paula Butterfield

Marie-Thérèse Reboul Vien: Finding the Natural in the Neoclassical, by Tori Champion

The Theatrical Wonders of Jeanne Paquin’s Belle Époque Parisienne, by Julia Westerman

Anna Boberg: Artist, Wife, Polar Explorer, by Isabelle Gapp

The Ongoing Revival of Matilda Browne, American Impressionist, by Alexandra Kiely

Adélaïde Labille-Guiard: Artist, Friend, Teacher, by Jessica L. Fripp

Seductive Surfaces: Anne Vallayer-Coster’s Vase of Flowers and Conch Shell at the Met, by Kelsey Brosnan

Marie-Guillemine Benoist, Revolutionary Painter, by Paris Spies-Gans

Trackbacks/Pingbacks