Reflections on the occasion of her birthday, 25th August

Guest post by Victoria Carruthers, the Australian Catholic University

On the opening page of her first memoir, entitled Birthday (1986), American artist Dorothea Tanning tells us that “the beginning is an impossible place.” In doing this, she hoped to remind us of the complexity of storytelling, and the impossibility of attempting to distill the richness of lived experience into a single narrative or representation.

Her second memoir is entitled Between Lives (2001). Perhaps both titles allude to a way of understanding her intensely creative life. Her body of work spanned more than seventy years of ceaseless experimentation and included painting, drawing, print and etching, sculptures, fabric installation, etchings, jewellery, costume and set designs, collage, fiction and a considerable body of poetry.

For Tanning, “birthdays,” as a mark of beginnings, were a metaphor for transformation. Accordingly, her characters are often caught in states of physical, emotional or psychological metamorphosis. Her work demonstrates a preoccupation with thresholds—liminal and transitional spaces in which fantasy, reality, sensation and imagination converge. From the outset, repeated motifs of doors, wallpaper and cloth are symbols of these thresholds that reveal otherworldly events folded into mundane, everyday spaces.

Birthday

Tanning was born in 1910 in Galesburg, Illinois, a town in which she declared “nothing ever happened but the wallpaper.” Yet she spent a lifetime imagining what might be happening just under the surfaces of those neatly furnished sitting-rooms.

A self-taught creator, she sustained herself as a successful commercial artist while pursuing her own painting. She was in New York as the surrealists began to arrive, exiled or rescued from a ravaged Europe, and she forged deep friendships with the likes of John Cage, Marcel Duchamp, Joseph Cornell and Lee Miller.

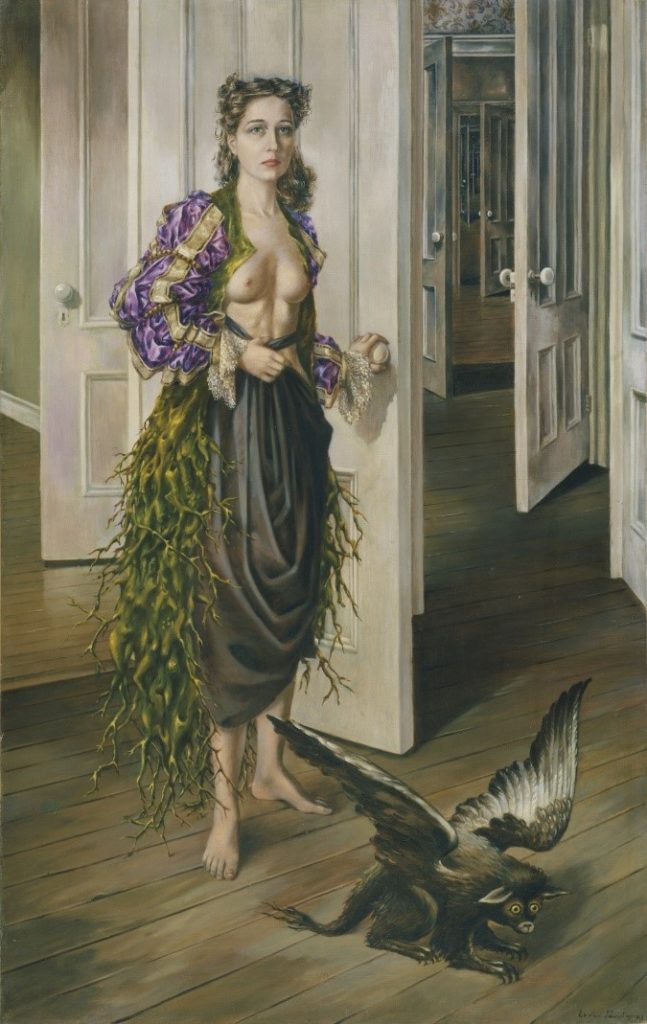

While steeped in this artistic milieu and heavily influenced by surrealism, Tanning painted some of her best-known works. In Birthday (1942), the artist depicts herself in the process of metamorphosis, a “rebirth” from one state to another.

She is strangely composed of hybrid parts, a fusion between reality and fantasy, mundane and magical, urban and rustic. The overall impression of the figure is of a chrysalis emerging from a cocoon. A fusion of both nature and culture, this dazzling young woman stands on the threshold of an unknown, yet exciting, adventure. The technical skill demonstrated in Birthday—its clarity and precision, typical of the surrealist style—intensifies the effect of the interwoven strands of fantasy and reality.

In 1999, the Philadelphia Museum of Art acquired Birthday. In the brochure for the survey show, entitled “Birthday and Beyond,” Tanning noted of the painting:

It was a modest canvas by present-day standards. But it filled my New York studio, the apartment’s back room, as if it had always been there. For one thing, it was the room; I had been struck, one day, by a fascinating array of doors—hall, kitchen, bathroom, studio—crowded together, soliciting my attention with their antic planes, light, shadows, imminent openings and shuttings. From there it was an easy leap to a dream of countless doors. Moreover, alone and taking stock of myself, I felt a sort of immanence as if my life was revealing itself at last—a real birthday.

The “immanence” of “a real birthday,” rather than a calendar one, is a sentiment that captures the multi-layered significance of the “rebirth” Tanning experienced in 1942. This was also the year Max Ernst came to her apartment on Julien Levy’s recommendation to see if she had anything suitable for a show his then wife, Peggy Guggenheim, was planning. Tanning herself has outlined the details of their meeting in both of her memoirs, but Ernst was so impressed by the painting, and presumably by Tanning herself, that he suggested a game of chess after spotting the board and pieces set up in the apartment.

The story which follows is that he never really left. While this may be a slightly poetic gloss over the practicalities of the period, it is also indicative of the intensity between these two artists, and gives us an insight into the type of “bohemian” lifestyle they would pursue. Near the end of her life, in 1999, Tanning explained that she had never liked celebrating her actual birthday and that she viewed the meeting with Ernst as her symbolic “birthday.” Accordingly, she had always celebrated it on November 24th (their meeting day) as opposed to the date on her birth register (August 25th).

Rebirth

The theme of the transformative potential of the “birthday” is more violently imagined in the 1943 short story “Blind Date,” which Tanning published in the short-lived surrealist journal VVV. The piece contains the familiar imagery of doors as indicators of a threshold, as well as the language of physical and psychological excess found in surrealist writing. But, again, Tanning uses the metaphor of rebirth to indicate the pain, delirium and catharsis of a powerful state of creative transformation:

Today you have been born, out of abysmal sorrow and knowledge, out of symbols, destructions, warnings, wounds, pestilence, instruments sacred and obscene, spasms, defilements; out of hates, and holocausts, guts and gothic grandeurs, frenzy, crimes, visions, scorpions, secretions, love and the devil. Today you shall be married to your future.

Tanning relates the physical extremes of birth and conscious awakenings to the larger texture of the violent drama of human history. By doing this she brings together the acts of creation, procreation and destruction, showing us how easily they fold into and around each other in a continuum of life experience. She also describes an intimate account of the creative process in all its explosiveness.

The notion of the “birthday” resurfaces multiple times in the artist’s work. It symbolised an important threshold, a powerful and deeply personal transformative state, rather than the celebration of mere natality. This sentiment is reflected in one of Tanning’s poems published in 2002, entitled “Secret.” The final lines leave us with an image of a world replete with imaginative potential:

In summer the park, for an hour or so before night, is at its greenest, a whole implicit proposition of green leaves, a triumph of leaves enfolding me that day in a green intimacy so trustworthy I told them my secret. “It’s my birthday,” I said out loud before turning away to cross the avenue

States of flux

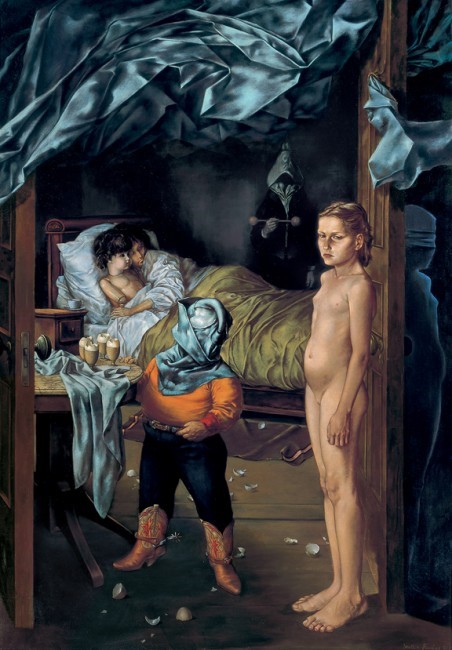

Tanning’s work often satellites around the feminine form, its boundaries, movements, abstractions and sensations. She was fascinated with the lived experience of the female body in maternity or when confronted by violence. She depicted childhood and puberty in enigmatic works like The Guest Room (1952) as both desired and dreaded.

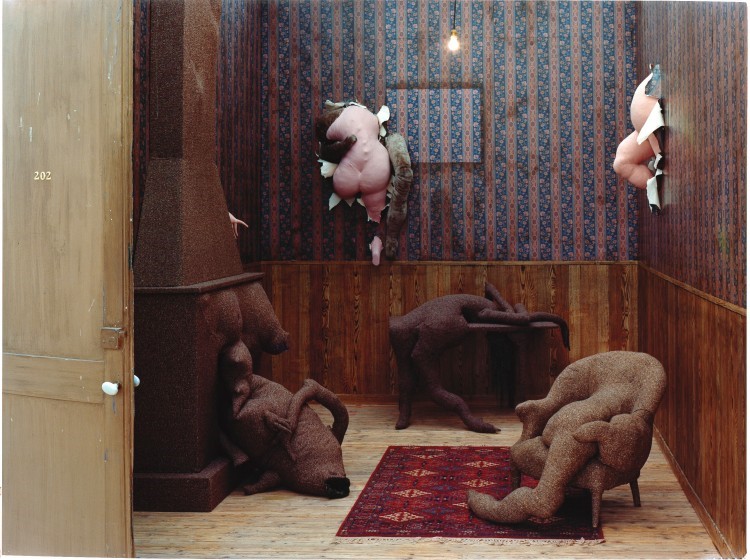

Tanning explored relationship dynamics—in families, among strangers, in the bond between human and animals (particularly dogs)—through voluptuous surfaces of paint, cloth or tissue paper that convey a sense of perpetual transformation. In works like Family Portrait (1977) she visibly collapses the boundaries between her figures to engage the imagination of any viewer.

One of the key impulses driving her work was to capture the multi-layered nature of lived experience. As she stated:

I’ve been trying for a long time to deal with the figures that emerge on the canvas. Time is needed to know them. In the first years, I was painting our side of the mirror—the mirror for me is a door—but I think that I’ve gone over, to a place where one no longer faces identities at all. One looks at them somewhat obliquely, slyly. To capture the moment, to accept it with all its complex identities.

Tanning’s later works continue to demonstrate this as her characters emerge from and recede into layers of sumptuous paint

or as they transform into hybrid states which create expansive, yet enigmatic imagery.

Always creating

Having moved to France in the 1950s with Ernst, Tanning returned permanently to New York in 1980 soon after his death in 1976. At 70, she became increasingly interested in writing, becoming an accomplished and well-published poet.

She was still producing extraordinary work when I met her in 2000, having just produced what would be her final body of work, a series of very large flower paintings in 1998.

I would often visit her apartment and we would talk about her work and life and then drink champagne. Our friendship lasted until her death in 2012, at 101. She was mischievous, generous, clever, funny, encouraging, surprising, willful and utterly amazing. By the end of her life she hated the idea of another birthday (unsurprisingly) but she had forged an entirely creative and truly unique life.

In the spotlight once more

Her consummate skill as an artist was acknowledged among her peers throughout her life, and her work features in international galleries including Tate, San Francisco and New York Museums of Modern Art, and the Pompidou Centre in Paris.

Tanning’s work has recently returned to the spotlight in recognition of its unique contribution to visual art. The first major retrospective of her work in 25 years was held at Museo Nacional Centra de Arte Reina Sofía in Spain and London’s Tate Modern last year. Her work was also included in the 2013 Venice Biennale.

Currently the Alison Jacques Gallery in London is presenting a series of videos that focus in depth on individual pieces. Now showing is “Dorothea Tanning: Mermaids and Metaphors,” (the title of an essay by myself and Catriona McAra), which examines the imagery and inspiration found in Tanning’s enigmatic painting Pour Gustave l’adoré (1974). The video is available to view through August 31.

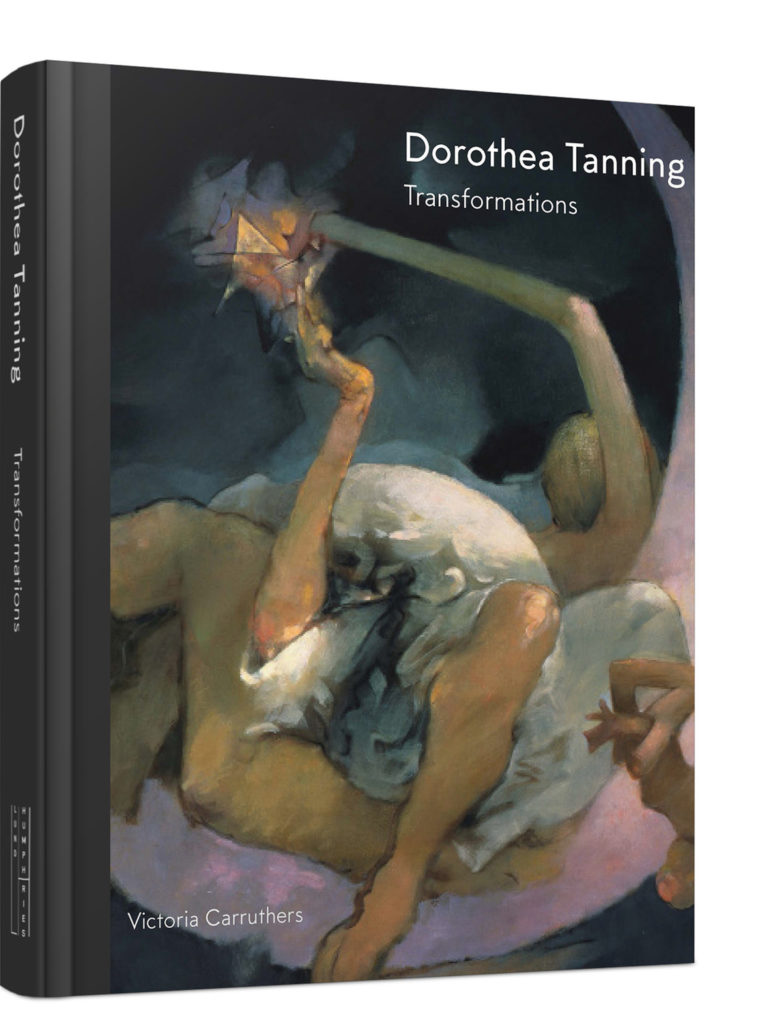

Scholars have also begun paying more attention to her work. My monograph Dorothea Tanning: Transformations, published earlier this year, is the first book devoted to exploring every aspect her work, tracing recurrent themes and preoccupations across her career. As an artist interested in exploring the richness of human experience from a distinctly feminine viewpoint, Tanning’s work occupies a singular position in the history of modern art.

Dr. Victoria Carruthers is Senior Lecturer in modern and contemporary art history and theory at the Australian Catholic University, Sydney, Australia. Her research explores the intersections between art, literature and music across visual cultures in the twentieth century. She completed her doctoral thesis on the work of Dorothea Tanning and has published several articles on her practice. She was fortunate enough to visit the artist on a number of occasions and enjoy many lengthy conversations on her life and work. Victoria’s book Dorothea Tanning: Transformations (Lund Humphries, 2020) is the first monograph on the artist.

If you liked this Art Herstory guest blog post, you might also enjoy:

Sculpture or Suffrage: Alice Morgan Wright, by Jennifer Dasal

Modern Women Artists in Copenhagen 2024–2025: Three Exhibitions, by Alice M. Rudy Price

Frida: Beyond the Myth at the Dallas Museum of Art, by Olivia Turner

A Quiet Eye—The Unique Achievement of Sylvia Shaw Judson, by Rowena Loverance

Nancy Sharp: An Undeservedly Forgotten Exemplar of Modern British Painting, by Christopher Fauske

Reflections on the Audacious Art Activist and Trailblazer Augusta Savage, by Sandy Rattley

Women Artists from Savannah at the Telfair Academy Museum, by Julie Allen

Material Re-Enchantments: A Review of Remedios Varo: Science Fictions, by Suzanne Karr Schmidt

Evelyn De Morgan: Painting Truth and Beauty, by Sarah Hardy

Anna Ancher’s Vaccination and Scientific Motherhood, by Alice Price

Dalla Husband’s Contribution to Atelier 17, by Silvano Levy

Anna Boberg: Artist, Wife, Polar Explorer, by Isabelle Gapp

Happy Birthday, Fidelia Bridges! by Katherine Manthorne

The Ongoing Revival of Matilda Browne, American Impressionist, by Alexandra Kiely

Esther Pressoir: Imagining the Modern Woman, by Suzanne Scanlan

The Abstract-Impressionism of Berthe Morisot and Joan Mitchell, by novelist Paula Butterfield

The Theatrical Wonders of Jeanne Paquin’s Belle Époque Parisienne, by Julia Westerman

Victorine Meurent, More than a Model, by novelist Drēma Drudge

The Cheerful Abstractions of Alma Thomas, by Alexandra Kiely

Trackbacks/Pingbacks