Guest post by Jessica L. Fripp, Texas Christian University

On the value of women

In 1876, the heirs of the French painter Adélaïde Labille-Guiard donated two works, the Self-Portrait with Two Pupils, Marie-Gabrielle Capet and Marie Marguerite Carreaux de Rosemond (1785) and the Portrait of Madame Adélaïde (c. 1787) to the Louvre. The director of the national museums of France ultimately declined the generous gift in 1878, writing “it would be difficult to find a place in the national collections for these canvases of no artistic value” (quoted in Melissa Lee Hyde, “Femmes-Artistes and America from the Early Republic to the Gilded Age,” America Collects Eighteenth-Century Painting).

The Louvre’s loss became the Metropolitan Museum’s and the Speed Art Museum’s gain. One might assume the rejection was related to the then-prevalent belief that women artists’ works were “lesser” than those of their male counterparts.

But the Louvre had accepted a number of key works by Labille-Guiard’s contemporary, Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun, over the course of the century, including her Portrait of the painter Hubert Robert and her Self Portrait with daughter Julie in 1843, and a Portrait of Madame Molé-Reymond of the Comédie italienne in 1865. Perhaps the Louvre felt they had reached their quota of women painters-ironic, as when Labille-Guiard and Vigée-Lebrun were accepted into the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture on the same day in 1783, they fulfilled the Old Regime institution’s own quota of women artists, which was then limited to four.

Whatever the reason, Labille-Guiard has historically been overshadowed by Vigée-Lebrun, often relegated to a mere passing mention of their supposed rivalry. This was a rumor probably created by their status as women in an almost entirely male institution, rather than an actual hostility. Labille-Guiard is slowly but surely getting the attention she deserves, thanks to the scholarship of art historians Anne-Marie Passez, Laura Auricchio, and others. Without their foundational work, this essay and my own scholarship on Labille-Guiard would not be possible. Here, I briefly highlight her success as an artist on the eve of the French Revolution, her participation in a network of prominent artists, and her commitment to training a new generation of women painters.

Painting Community

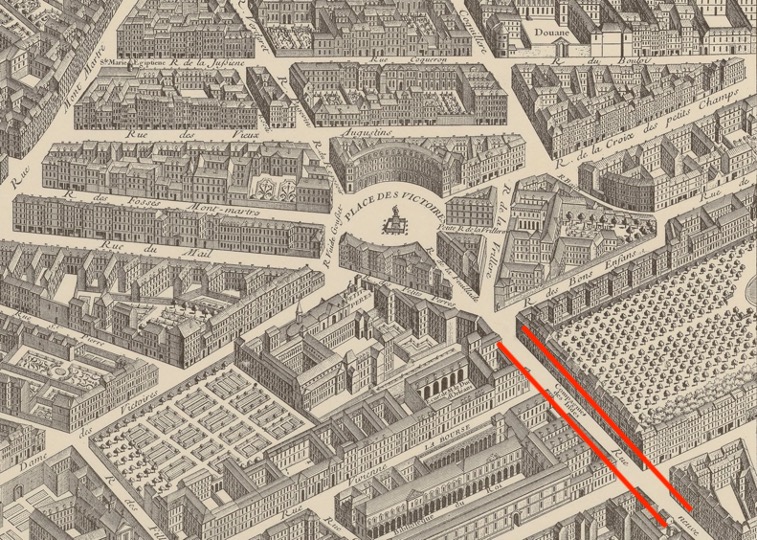

Born on April 11, 1749 on the rue Neuve des Petits Champs—a bustling neighborhood of artists right behind the Palais Royal—Labille-Guiard was the daughter of a marchand mercier (purveyor of fashionable objects) who owned a boutique called La Toilette.

As Clare Haru Crowston has demonstrated, fashion was a risky business, and it was common for shops like La Toilette to fold under the accumulation of debt inherent to the eighteenth-century fashion system. This is perhaps why, in 1761, Labille-Guiard’s father sold the contents of his shop three years after becoming a receveur (seller of tickets) for the new and highly profitable lottery: the lotérie de l’École militaire. The profit from the boutique’s sale, coupled with the consistent income from her father’s new career, may have factored into the start of Labille-Guiard’s career.

In 1763, when she was fourteen, she began her artistic training with a neighbor, the miniaturist François-Élie Vincent. By 1769, she was a member of the Académie de Saint-Luc, and married to a man she separated from in 1779. She then became a student of Vincent’s son, François-André Vincent, after he returned from Rome in 1775. The friendship between François-André Vincent and Labille-Guiard was lifelong, and the two would marry in 1800.

Her relationship with the younger Vincent provided an introduction to Vincent’s teacher, Joseph-Marie Vien, husband of the academician Marie-Thérèse Réboul, and his active studio of up-and-coming young artists. In May of 1783, she was presented for acceptance into the Royal Academy by Alexandre Roslin, husband of the recently deceased academician Marie-Suzanne Giroust.

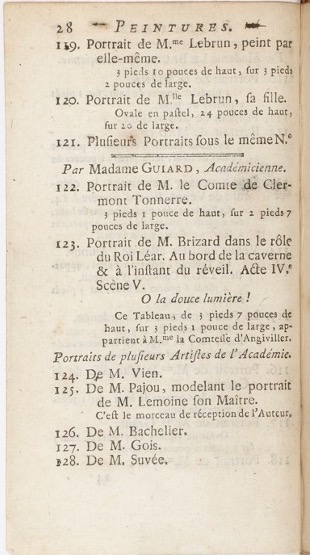

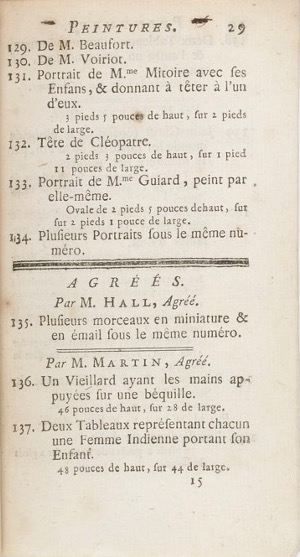

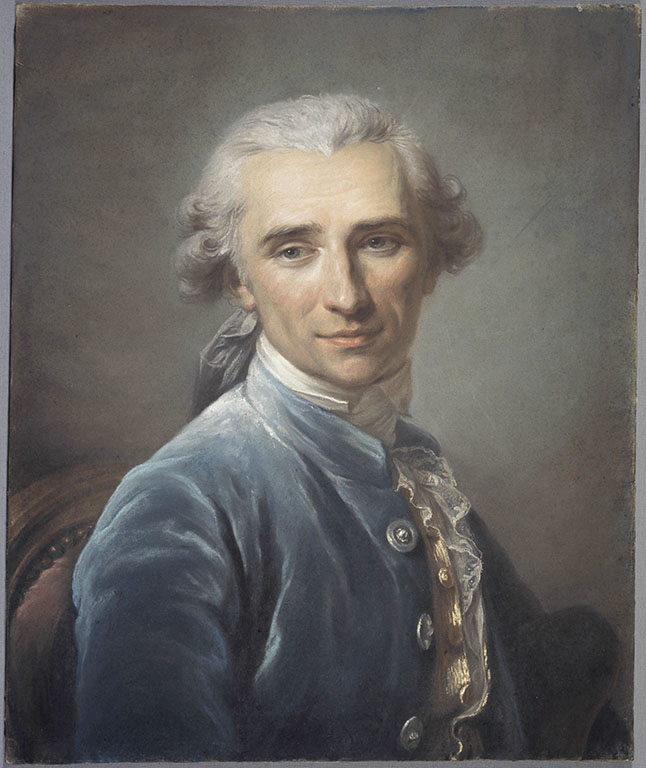

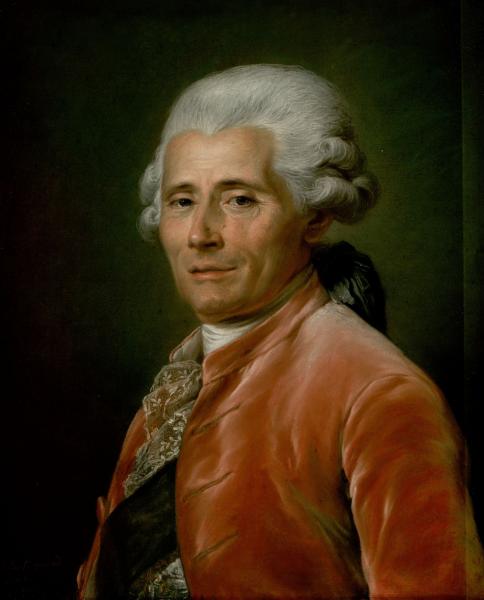

The community of artists she met through Vien and Vincent was very important to Labille-Guiard, which was demonstrated at her first official Salon appearance in 1783. Her submissions included seven pastel portraits of artists: Vien, Jean-Jacques Bachelier, Guillaume Voiriot, Jacques-Antoine Beaufort, Étienne-Pierre-Adrien Gois, and Joseph-Benoît Suvée, Augustin Pajou, as well as her own self portrait in pastel.

The portraits were well-received, described in the Année Littéraire as allowing the viewer to “imagine they are conversing with the faithful image of the person she offers, by the easy manner and their noticeable facility: one can sense as it were the spirit and character of each of her models: the soul appears painted on their face.”

Prior to her acceptance into the Academy, she had displayed most of these portraits at an unofficial exhibition known as the Salon de la Correspondance, organized by the entrepreneur Pahin de la Blancherie. These portraits are evidence that she was part of a group of artists made up of both student/teacher and student/student relationships, and some of them were exchanged amongst the sitters.

Suvée was Bachelier’s student, who lived with Bachelier before winning the Prix de Rome in 1771. Labille-Guiard’s portrait of Vincent (displayed at Salon de la Correspondance but not at her début Salon) ended up in Suvée’s collection. Suvée’s portrait was likewise destined for Vincent. Suvée and Vincent had become close during their stay at the Palais Mancini in Rome as Prix de Rome winners. Both artists signed the wedding contract of one of Labille-Guiard’s students, Jeanne Bernard, in Labille-Guiard’s home.

“A portrait composed in the genre of history”

Despite the relative success of her 1783 works, Labille-Guiard’s career began to stall. This is likely why she exhibited, at the Salon of 1785, the ambitious group portrait Self-Portrait with Two Pupils, Marie-Gabrielle Capet and Marie Marguerite Carreaux de Rosemond, a work today considered her masterpiece. It remained in her collection her entire life. With its large size and virtuoso treatment of silk, lace, and other luxurious materials, the work served as publicity for Labille-Guiard’s talent as a portrait painter. It also offered a demonstration of female friendship, and of Labille-Guiard’s commitment to training other women to follow in her footsteps.

The depiction of Capet and Carreaux de Rosemond, their arms wrapped around each other, eagerly crowding around their teacher to examine the large canvas she works upon, is a powerful counterpoint to the celebration of male friendship and education that she had displayed in her previous Salon. The author of the Observations critiques sur les Tableaux du Sallon described the Self-Portrait as a “portrait composed in the genre of history, and in which one recognizes a vigorous touch, demonstrating the talent of the artist.”

He was not the only person to take note of the painting; it caught the eyes of the aunts of King Louis XVI, Madame Adélaïde and Madame Victoire. In 1787, her Salon paintings included portraits of the Mesdames, as the aunts were collectively known (including the original version of the portrait today in the Speed Art Museum). Her new title was listed in the Salon catalogue: Painter to the Mesdames.

A Dedicated Teacher

While the large Self-Portrait helped Labille-Guiard’s career take off, it is more importantly a declaration of Labille-Guiard’s dedication to training women artists. According to a critic of the Exposition de la Jeunesse, an exhibition venue open to artists who were not part of the Royal Academy, Labille-Guiard’s students “number[ed] nine, all of them pretty and likable, constituting an assembly of nine muses in the cradle of which Mme Guyard is the teacher (institutrice).” Yet, this too had its pitfalls: her numerous female students prevented her from receiving lodging in the Louvre palace. There were concerns about what might happen if young men and women were allowed to mingle in the palace. (To quote Louis XVI’s art administrator, the Comte d’Angiviller: “…all the artists have their lodgings in the Louvre, and as one only gets to all these lodgings through vast corridors that are often dark, this mixing of young artists of different sexes would be very inconvenient for morals and for the decency of Your Majesty’s palace.”)

Notably, these slights left Labille-Guiard undeterred. During the debates about the future of the Academy in early years of the Revolution, Labille-Guiard was a staunch advocate of eliminating the limits on women members and fought for professional artistic training for women. One of the two students in the 1785 portrait, Marie-Gabrielle Capet, lived with Labille-Guiard and Vincent.

During the heady years of the Revolution between 1792 and 1795, the trio moved to a house in Pontault-en-Brie, a town just outside of Paris. Vincent and Labille-Guiard married in 1800 (she was finally allowed to divorce her estranged husband when divorce became legal under the new Revolutionary government). After Labille-Guiard’s death in 1803, at the age of 54, Capet continued to take care of Vincent.

Capet paid homage to her teacher with her 1808 painting, A Painting representing the late Madame Vincent (student of her husband). She is busy making a portrait of M. Senator Vien, comte de l’Empire and member of the Institute of France, regenerator of the French school, and Vincent’s teacher. The artist, who is represented charging her palette, has put the principal students of M. Vincent into this painting. The painting shows Labille-Guiard at her easel in a well-appointed, crowded studio, porte-crayon in hand. Capet herself is seated at a miniature desk in the foreground, a reference to the medium for which she was best known.

She looks at the viewer, momentarily distracted from her task of preparing Labille-Guiard’s palette with color in anticipation of her teacher finishing the underdrawing for the portrait and switching to work in oil paint. Vincent stands behind his wife, gesturing to something on her canvas, which is turned away from the viewer. Vien, the subject of the work in progress, sits in his senatorial costume, with his son and daughter-in-law behind him. The rest of the crowd is made up of nine of Vincent’s students (perhaps a reference to Labille-Guiard’s “nine muses”).

By 1808, Vien was considered the grand patriarch of the French school of painting. He was also Capet’s artistic “great-grandfather,” so to speak. Vien had trained Vincent, who trained Labille-Guiard, who, in turn, taught Capet. The work asserted Capet’s place as one of Vien’s descendants while simultaneously honoring Labille-Guiard. The painting is a tribute to her friendship network, the greatness of the French school, and her teacher.

Jessica L. Fripp is Associate Professor of Art History at Texas Christian University, where she teaches European art from 1700 to 1945. Her research focuses on the intersection of visual culture and social relationships. She is the author of Portraiture and Friendship in Enlightenment France (University of Delaware Press, 2020), co-editor of Artistes, savants et amateurs: art et sociabilité au XVIIIe siècle (1715-1815) (Mare et Martin, 2016), and her work has appeared in Eighteenth-Century Studies and Eighteenth-Century Fiction. You can find her on twitter: @jlfripp

More Art Herstory blog posts about French women artists:

Charlotte Eustache Sophie de Fuligny-Damas, Marquise de Grollier, by David Pullins

Louise Moillon: A pioneering painter of still life, by Lesley Stevenson

Marie Laurencin and the Autonomy of Self-Representation, by Mary Creed

The Many Faces of Suzanne Valadon, by Suzanne Singletary

Marie-Thérèse Reboul Vien: Finding the Natural in the Neoclassical, by Tori Champion

Madeleine Françoise Basseporte’s Hyacinths at the French Court, by Mary Creed

Seductive Surfaces: Anne Vallayer-Coster’s Vase of Flowers and Conch Shell at the Met, by Kelsey Brosnan

Marie-Guillemine Benoist, Revolutionary Painter, by Paris Spies-Gans

The Theatrical Wonders of Jeanne Paquin’s Belle Époque Parisienne, by Julia Westerman

Victorine Meurent, More than a Model, by novelist Drēma Drudge

More Art Herstory blog posts about 18th-century women artists:

Exhibiting Women: The Art of Professionalism in London and Paris, 1760–1830, by Paris Spies-Gans

Mary Linwood’s Balancing Act, by Heidi A. Strobel

A Short Reintroduction to the Life of Anna Dorothea Therbusch (1721–1782), by Christina K. Lindeman

Rosalba Carriera at The Frick Collection, by Xavier F. Salomon

Angelica Kauffmann: Grace and Strength, by Anita V. Sganzerla

Angelica Kauffman and Mary Moser: Founding Women Artists of the Royal Academy

“I feel again the violence of a curious desire”: Rare client testimonies on Rosalba Carriera’s erotic art, by Angela Oberer

Rediscovering the Once Visible: Eighteenth-Century Florentine Artist Violante Ferroni, by Ann Golob

Trackbacks/Pingbacks