Guest post by Babette Bohn, Texas Christian University

Why Bologna?

The north Italian city of Bologna produced the largest and most successful group of women artists in early modern Italy. Bologna is the real protagonist of my new book, Women Artists, Their Patrons, and Their Publics in Early Modern Bologna (Pennsylvania State University Press, 2021; fig. 1). Founded on extensive archival research, the book examines sixty-eight women who were painters, sculptors, printmakers, embroiderers, and disegnatrici (draftswomen) from the fifteenth through the eighteenth centuries.

No other city comes close to these numbers, and none matches the diverse specializations and impressive public record of this accomplished group. I investigate individual artists, from well-known painters such as Lavinia Fontana (1552–1614) and Elisabetta Sirani (1638–1665) to more obscure figures such as the etcher Maria Elisabetta Macchiavelli (1692–1727) and the sculptor Clarice Fortunata Pellegrini Vasini (1732–1823). The book explores the reasons for women’s unusual success in Bologna. Key factors included

- exceptional local biographers;

- unusually diverse patrons and collectors;

- earlier accomplished women in literature, academic fields, and religion;

- Bologna’s venerable university and reform-minded archbishops; and

- the unprecedented celebration of women’s drawings.

How to Measure Success

The sixty-eight Bolognese women artists recorded by early writers or documents provide a striking barometer of success. During the seventeenth century, the forty-four women artists in the city far exceed the numbers recorded elsewhere, even in the much larger cities of Venice, Naples, and Rome. This discrepancy suggests an environment that was unusually receptive to female agency.

Bolognese women’s many public commissions also confirm their accomplishments. During the seventeenth century, twenty-five women received commissions for prestigious and lucrative public works such as altarpieces. Even earlier, around 1525, Properzia de’ Rossi, the first woman to receive a public commission in Bologna, created marble sculptures for the Basilica of San Petronio (fig. 2). Properzia was also the sole woman to receive a biography in the first edition of Giorgio Vasari’s Lives of the Artists (1550). Lavinia Fontana, whose achievements were described by more writers than any other woman artist of the sixteenth century, earned an unprecedented twenty-four public commissions for paintings. And Elisabetta Sirani produced even more: some thirty-five public pictures between 1655 and 1665. Her altarpiece of The Christ Child appearing to Saint Anthony (fig. 3, 1662), painted for the Church of Saints Leonardo and Ursula, brings a characteristic sense of tenderness and intimacy to her devotional figures.

Context and Patronage

Bologna housed the oldest university in Europe, and many women artists came from academic families or worked for university scholars. The city was also a center for book publishing and religious reform, which both yielded opportunities for women. Moreover, Bologna celebrated its accomplished women writers, scholars, and religious figures, dating back to the thirteenth century. Caterina Vigri (1413–1463), a nun who founded the Corpus Domini convent, was also the first recorded woman painter in Bologna. Her example sanitized the painter’s profession for women, particularly after her beatification in 1592 and canonization in 1712. She became the patron saint of Bologna’s Accademia Clementina in 1710.

Although Vigri worked exclusively within her convent, later women benefited from the growing socioeconomic diversity of patrons and collectors in the city. Unlike some cities, Bologna was not a court, and patronage was not dominated by one ruling family after the fifteenth century. As Raffaella Morselli has shown, patrons and collectors from varied income levels promoted artistic production. They included fishmongers, jewelers, bankers, cloth merchants, ecclesiastics, and nobles, among others. I suggest that Bolognese women produced some of their most original works for middle-income patrons who were receptive to iconographic innovations.

Training

The painter Elisabetta Sirani was a pivotal figure, achieving great success and inspiring many other women to pursue artistic careers. Earlier studies exaggerated her influence, hypothesizing that most of her successors were her students. My archival research uncovered new dates for many women, confirming that most of them could not have studied directly with Sirani. Instead, they were evidently inspired by her example. One consequence of this discovery is the realization that many women studied with men who were not family members. The widespread character of this phenomenon began in the later seventeenth century, when more than half of recorded women artists studied with male non-relatives. This suggests that social and professional conventions were changing, enabling more women to become artists.

Bolognese Biographers and Signing Practices

One chapter examines how local writers contributed to the appreciation of their female compatriots. Most early modern biographies of women artists emphasize their beauty, virtue, and personal lives at the expense of their work. I argue that Bolognese biographers, beginning with Carlo Cesare Malvasia in 1678, treated women as professionals, focusing instead on their artistic production and promoting a fuller appreciation of their works. These biographies have contributed significantly to larger extant oeuvres for many women, a situation also promoted by numerous signed paintings and sculptures. Most extant paintings by Sirani and most extant sculptures by Vasini (fig. 4) are signed, facilitating recognition of their works today. Since male artists in Bologna rarely signed, this method of claiming authorship is a distinctive feature of Bolognese women’s artistic practices.

Artists

In 1976, Ann Sutherland Harris first recognized Lavinia Fontana as the earliest professional woman artist in Italy. She worked in the marketplace rather than a court or convent, receiving commissions from different patrons. She was especially famous for her portraits (fig. 5),

which constitute over half of her oeuvre, and she also painted many public and private religious pictures (fig. 6).

Sirani died at the age of twenty-seven, so her short career lasted scarcely more than a decade. But thanks to her list of some 200 paintings that Malvasia published in his biography, we know that she was productive nevertheless. Unlike Fontana, most of Sirani’s paintings portrayed religious subjects, and her privately commissioned paintings of the Madonna and Child were especially popular (fig. 7).

Like her two famous predecessors, Lucia Casalini Torelli (c. 1680–1762) painted both portraits and altarpieces. And like them, she produced several remarkable self-portraits (fig. 8). Casalini was one of fifteen Bolognese women to receive an honorary membership in Bologna’s new artist’s academy, the Accademia Clementina, founded in 1709.

As in other cities, most of Bologna’s female artists were painters, although uniquely, it also boasted three sculptors. Anna Morandi Manzolini (fig. 9) was the most famous, winning memberships in more academies than any other woman artist to date.

But despite her international reputation, prestigious commissions, and position at the university, she was never financially secure. Tragically, she was forced to relinquish one of her two children and to sell her entire collection of wax sculptures to make ends meet. In contrast, top painters like Fontana and Sirani were financially successful. Malvasia remarks on the high prices Fontana commanded for her portraits of noblewomen, comparing them to the compensation earned by such eminent portraitists as Anthony van Dyck. Perhaps it was easier for painters to obtain generous compensation than for women in other specializations. My rediscovery of the woodcutter Veronica Fontana’s will confirms that despite her many commissions, she died in poverty.

Drawings

One frustration of studying women artists in early modern Italy is the paucity of drawings that can be reliably credited to them. This limits our understanding, since drawings for most Italian artists were crucial in both education and pictorial preparation. Elsewhere in Italy, only a few drawings by women artists such as Sofonisba Anguissola are still identifiable. Thus the existence of drawings by a number of Bolognese women offers a rare opportunity. About thirty drawings can be reliably ascribed to Lavinia Fontana, including several that prepared paintings.

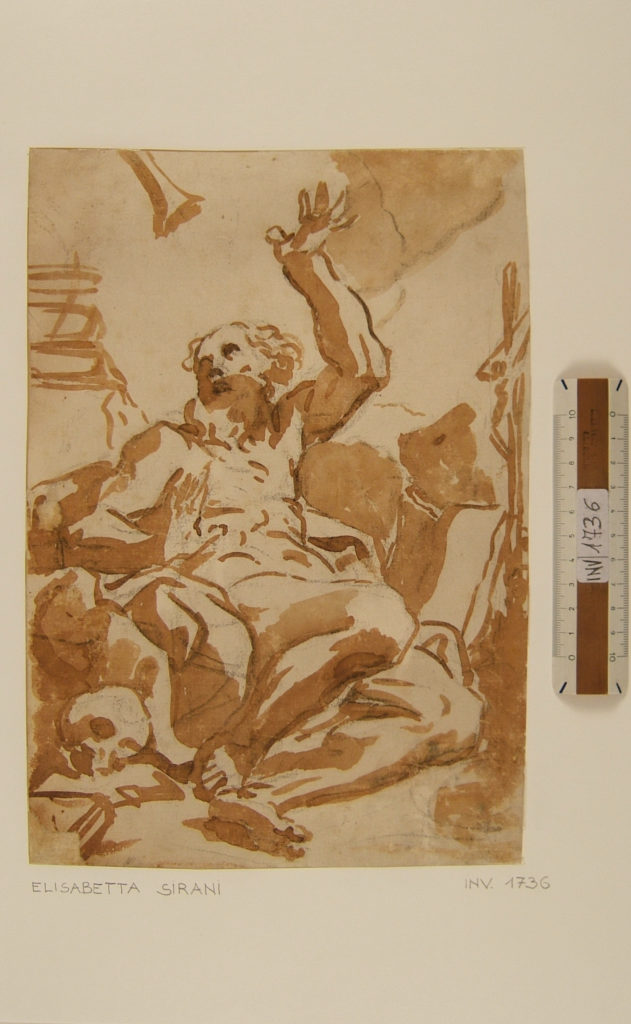

But the first Italian woman to be famous explicitly for her drawings was Elisabetta Sirani, by whom some 150 drawings are identifiable. Malvasia collected Sirani’s drawings and especially admired her facility with wash, which he thought reflected her consummate skill. The Saint Jerome (fig. 10), a study for a painting, illustrates the dynamic, expressive quality of the artist’s wash drawings. My book also presents some red chalk drawings that are newly connected to Sirani’s paintings. Only a few later women produced drawings that are still identifiable, so more work remains do be done on this important subject.

Conclusion

I’d like to conclude with some comments about my hopes for this new book. Because Bologna has so many, and such diverse, women artists, it provides an unusual opportunity to formulate some comprehensive hypotheses about women artists in early modern Italy. This broader scope may offer opportunities for understanding not just Bologna but also other cities where women worked. Three documentary appendices should provide useful starting points for scholars who wish to pursue little-known artists further. There are still quite a few with no identifiable works, so there are lots of opportunities for my successors. But most of the book is pitched to broader audiences, and I hope it will be engaging for anyone with an interest in women artists.

Babette Bohn, (Pennsylvania State University Press, 2021).

Dr. Babette Bohn is professor and graduate coordinator of art history at Texas Christian University. She has published numerous books and articles particularly on Bolognese women artists, drawings, and prints, and is the author of Ludovico Carracci and the Art of Drawing (2004) and Le “Stanze” di Guido Reni: Disegni del maestro e della scuola, an exhibition catalogue for the Uffizi Gallery, Florence. Her new book is Women Artists, Their Patrons, and Their Publics in Early Modern Bologna (Pennsylvania State University Press, 2021).

More Art Herstory guest posts about Bolognese women artists:

Plautilla Nelli and the Restoration of her Altarpiece Madonna del Rosario. by Jane Adams

Elisabetta Sirani’s Studio Visits as Self-Preservation: Protecting an Artistic Career, by Victor Sande-Aneiros

Stitching for Virtue: Lavinia Fontana, Elisabetta Sirani, and Textiles in Early Modern Bologna, by Dr. Patricia Rocco

The Restoration of Royalty: Lavinia Fontana’s Queen of Sheba and King Solomon, by Dr. Aoife Brady

Elisabetta Sirani: Self-Portraits, by Jacqueline Thalmann

Drawings by Bolognese Women Artists at Christ Church, Oxford, by Jacqueline Thalmann

Lavinia Fontana and Elisabetta Sirani at the Smith College Art Museum, by Dr. Danielle Carrabino

Elisabetta Sirani of Bologna (1638–1665), by Dr. Adelina Modesti

Lavinia Fontana: Italy’s First Female Professional Artist, by Dr. Elizabeth Lev

Sister Caterina Vigri (St. Catherine of Bologna) and “Drawing for Devotion,” by Dr. Kathleen G. Arthur

More Art Herstory guest posts about Italian women artists:

Three Historic Women Artists Exhibitions: A Dispatch from Italy, by Alessandra Masu

Roma Pittrice: Women Artists at Work in Rome Between the Sixteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, by Alessandra Masu

Maddalena Corvina’s Saint Catherine of Alexandria, by Kali Schliewenz

Judith’s Challenge, from Lavinia Fontana to Artemisia Gentileschi, by Alessandra Masu

By Her Hand: Personal Thoughts and Reflections on an Exhibition, by Oliver Tostmann

Sister Eufrasia Burlamacchi (Lucca, 1478–1548), by Dr. Loretta Vandi

Artemisia Gentileschi: What Wasn’t in the London Exhibition and Why it Matters, by Dr. Jesse Locker

“La grandezza del universo” nell’arte di Giovanna Garzoni / “The grandeur of the universe” in the art of Giovanna Garzoni (Guest post/review by Dr. Sara Matthews-Grieco)

Plautilla Bricci (1616–1705): A Talented Woman Architect in Baroque Rome, Guest post by Dr. Consuelo Lollobrigida

Renaissance Women Painting Themselves, Guest post by Dr. Katherine McIver

Orsola Maddalena Caccia (1596–1676), Convent Artist, Guest post by Dr. Angela Ghirardi

Two of a Kind: Giovanna Garzoni and Artemisia Gentileschi, by Dr. Mary D. Garrard

The Priceless Legacy of Artemisia Gentileschi: A Curator’s Perspective, by Dr. Judith W. Mann

Trackbacks/Pingbacks