Guest post by Silvano Levy, University of Hull

École de Paris beginnings

Gladys Dalla Husband arrived in Paris in 1924 at the age of 25 and worked in the studio of the Polish printmaker Józef Hecht, where she learnt the basics of printmaking. In 1927 she met Stanley William Hayter, following his exhibition at Le Sacre du Printemps gallery, and felt she could gain much from his expertise. With fellow artist Alice Carr de Creeft, she approached him for lessons in printmaking. Hayter was not keen on the proposal and attempted to deter the would-be students, saying he would only work with them if they brought two more. Bent on getting her way, Dalla did meet the conditions and Hayter, reluctantly perhaps, moved from his studio at 51, rue du Moulin Vert to larger premises, which allowed him to accommodate the enthusiastic printmakers. In 1933 he transferred the workshop to 17, rue Campagne-Première, near Montparnasse. It could be argued that Atelier 17, as it came to be known, came about as a result of Dalla’s determined initiative and may otherwise never have materialized.

Dalla exhibited in the 1929 Salon des Surindépendants and showed in Parisian, London, Prague and Canadian galleries. She is known to have exhibited at the Galerie Bonaparte in Paris, which specialized in prints. In addition to her artistic verve, Dalla was a committed and active socialist, as was Hayter, with whom she collaborated on politically-motivated projects. Like many of her contemporaries in artistic circles, she supported the Republican cause at the time of the Spanish Civil War and, in 1937, took the risk of travelling to Spain clandestinely, without papers, at the invitation of the Ministry of Arts of the Spanish Republican government. There she witnessed first-hand the havoc, misery and destruction wreaked by the conflict.

Solidarité and Fraternity

In response to her experiences, Dalla collaborated with Hayter to organize the printing of two fundraising publications. The first, Solidarité, was an edition of Éluard’s poem “Novembre 1936,” with a translation by the Irish poet Brian Coffey accompanied by signed, loosely-inserted illustrations by Joan Miró, Yves Tanguy, André Masson, John Buckland-Wright, Hayter, Husband and Picasso. The assortment of engravings and etchings was printed in Atelier 17; it was placed in portfolios printed and published on 15 April 1938 by the poet and publisher Guy Lévis Mano. The sale proceeds were intended to benefit the Republicans.

A year later, on 1 March 1939, a month before the end of the Spanish Civil War, Hayter and Husband produced Fraternity, another similar edition, this time in support of the Spanish Children’s Fund, which helped orphans of war. It featured the poem “Fall of a City” by the communist Stephen Spender, who had fought in Spain among the ranks of the International Brigades. The translation was by Aragon and the inserted 10 signed engravings were by Buckland-Wright, Hayter, Józef Hecht, Husband, Kandinsky, Roderick Mead, Miró, Dolf Rieser and Luis Vargas—the tenth being a second work by Hayter, an eau-forte, pasted on the cover.

Death in Mexico

At the outbreak of war Dalla left Paris for Canada and spent a year in West Vancouver. She missed the artistic vibrancy she had left behind and decided to join a group of Canadian artists working in Mexico. Dalla arrived there at the end of May 1940. Her sojourn of three years and two months in Mexico is undocumented, other than a plan for an exhibition in New York. The show never took place. Dalla developed septicaemia following an ear operation and died in hospital on 15 August 1943. The year of her death has also been documented as both 1944 and 1945. While in Mexico, she almost certainly met the surrealists who had escaped Europe after the invasion of Paris. No trace remains of Dalla’s Mexican work, which is currently totally unknown.

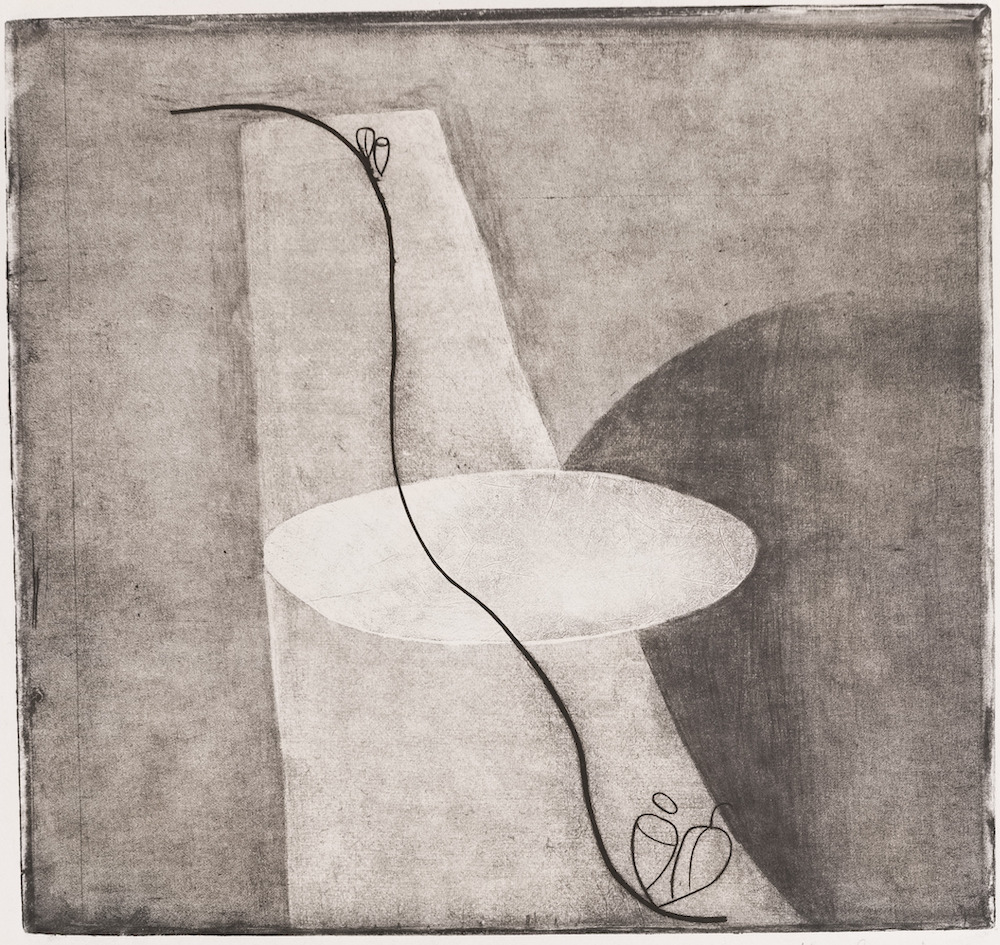

Etching for Solidarité

The studies for the Spain portfolios are a prime example of the emotional charge that exists in Dalla’s work. The five claustral compartments in her etching for Solidarité convey a sense of entrapment and incarceration. Groups of stylized biomorphic figures are confined within heavily delineated cuboid spaces.

In the lower right several forms seem to be looking to the right and upwards as though alarmed by something spotted or heard in the sky. Immediately above them, in another rectangle, a further gathering is busily interacting amongst itself: the suggestion is that of conversations or debates. The top right of the work may be taken to be a moment of realization that danger is looming. The protagonists appear to be in flight. They are all making a frantic dash to the right. As though to leave us in no doubt that the small troupe is running at full pelt, Dalla faithfully portrays the raised knee and upward-pointing foot of the runner on the far right. Given the context of the work, the allusion is clearly to the panicked and terrified civilians caught up in the fighting of the civil war.

On the left of the tableau a different story unfolds. There the compartments reveal barely any animation. The uppermost pair of characters is hunched-over and cowering in a confined space. The allusion is patently to the many civilians trapped and killed under the rubble of bombed buildings. Below them is what could be seen as the dénouement of this pictorial narrative sequence. The “figures” there are fragmented and hint at lacerated limbs and mangled, mutilated bodies. With her somewhat cryptic “storyboard,” Dalla maps out the horrific plight of the victims of the ongoing hostilities. At the time, her message would have needed little decoding.

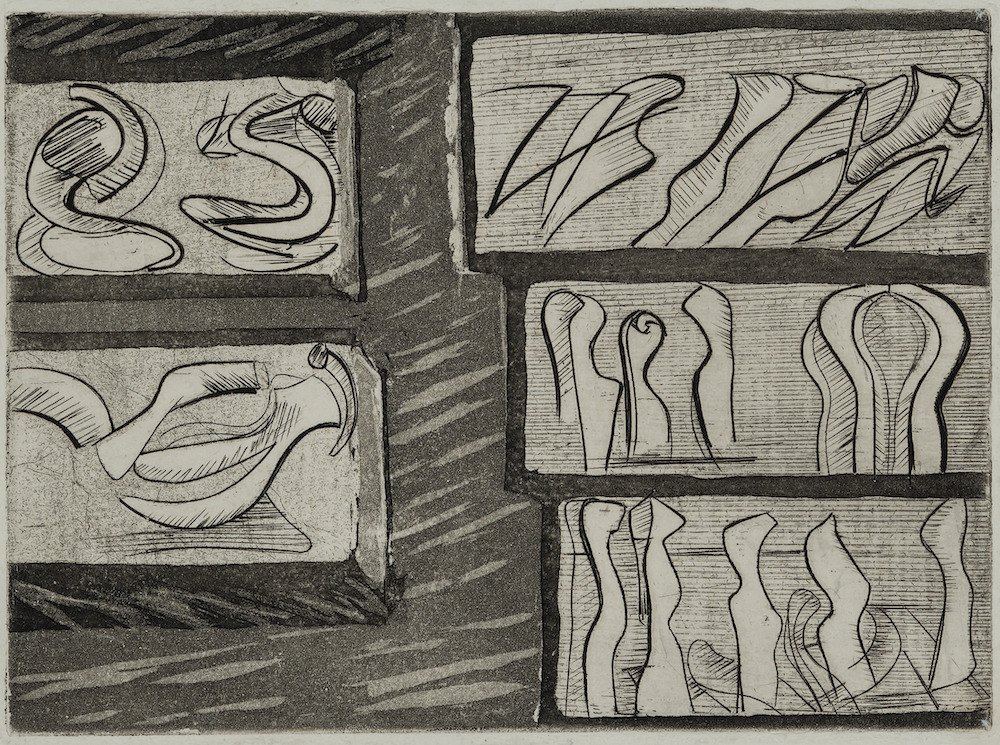

Etching for Fraternity

The etching for the 1939 portfolio depicts aggressors as well as victims. The work transparently focuses on the Nationalists’ aerial bombing campaign, which was marked by the unprecedented targeting of civilians. A particularly infamous raid was the one made on 26 April 1937 on the Basque town of Guernica by the Luftwaffe and the Aviazione Legionaria. Picasso had been outraged at the time and expressed his feelings in his anti-war painting Guernica (1937). Dalla’s work is in the same vein.

In the foreground large slabs resembling fallen masonry lie strewn on what could be a city street. In the middle distance anthropomorphic forms cram together in a panicked throng. They are seen making a mad dash through narrow passages. Among them is a child. These are clearly not combatants, but the vulnerable and the weak. Above them the hostile aircraft are about to wreak havoc. As though to emphasize the malevolence of the attackers, Dalla gives the bombers huge black eyes, like those of birds of prey. This is a work of extreme and contrasting emotions. The terror of the defenceless civilians is coupled with the callousness of their assailants. The moment depicted is that immediately before a holocaust. To add to the drama, Dalla’s composition conjures up a cacophony of noise—the crashing of falling buildings, the scuttling and screams of the crowds scrambling for safely, the roar of propellers, the booming of exploding bombs, the clangour of scattering shrapnel.

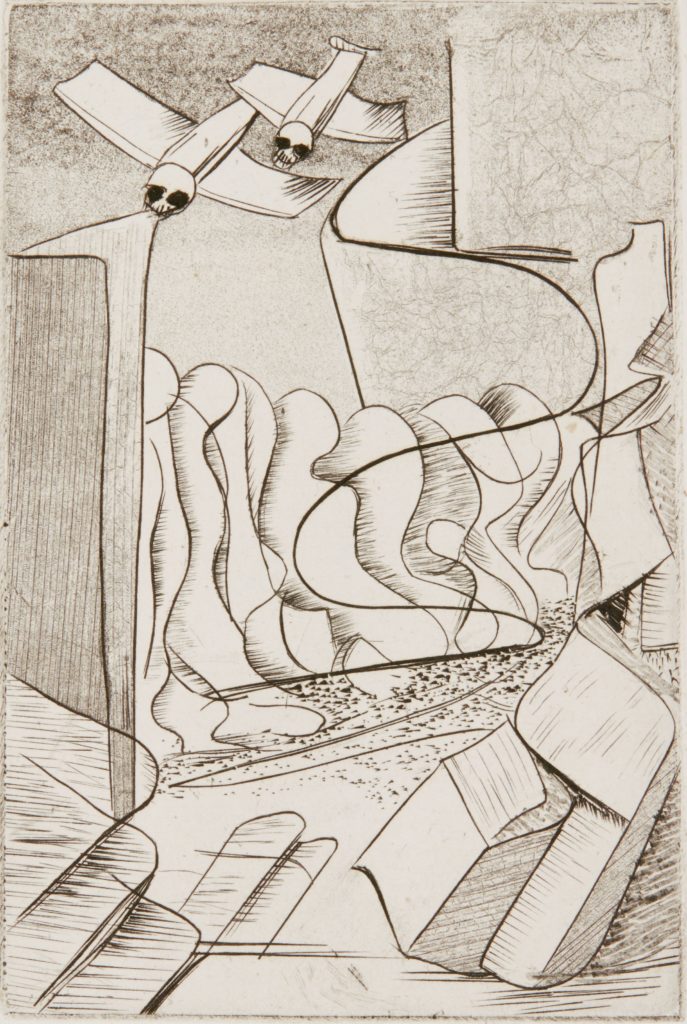

20.5 x 16.2 cm, image: 19.9 x 16 cm, Plate 8 from Dalla Husband & Langston Hughes, Madrid 1937 (Paris: Gonzalo More, 1939). Collection of the Winnipeg Art Gallery. Acquired with funds from The Winnipeg Foundation, G-86-393. Photo: Courtesy of the Winnipeg Art Gallery.

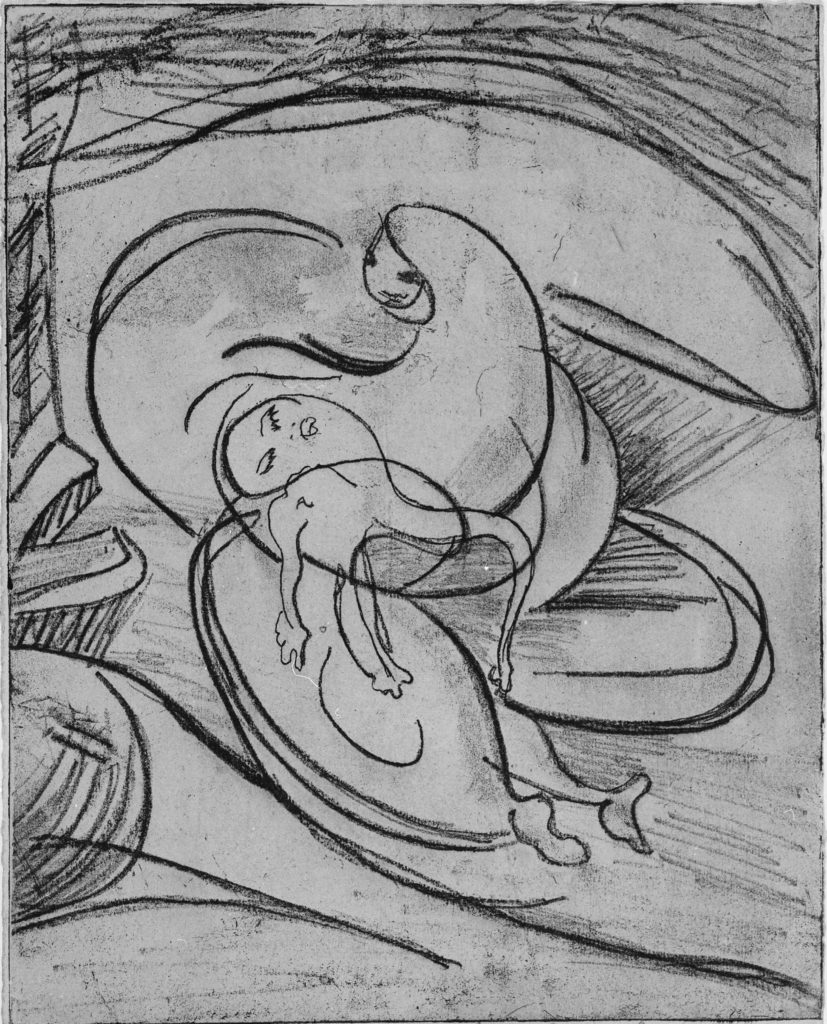

32.5 x 25 cm, image: 13.9 x 17.9 cm, Plate 5 from Dalla Husband & Langston Hughes, Madrid 1937 (Paris: Gonzalo More, 1939). Collection of the Winnipeg Art Gallery. Acquired with the assistance of a repatriation grant from the Government of Canada through the Cultural Property Export and Import Act, G-88-491. Photo: Ernest Mayer, courtesy of the Winnipeg Art Gallery.

Other Spanish Civil War Etchings

In addition to her Solidarité and Fraternity contributions, Dalla executed a moving series of nine works that focus not so much on combat as on its aftermath. The set of etchings was assembled into a hitherto unknown and undocumented portfolio made in collaboration with Missouri-born journalist Langston Hughes, who contributed his poem “Madrid” to the publication. Among his verses are the laments “Beneath the bullets! / Madrid! / Beneath the bombing planes! / Madrid! / In the fearful dark!” In June 1937 Hughes had been sent by his Baltimore Afro-American newspaper to write about Black Americans volunteering in the International Brigades. The Madrid portfolio, illustrated solely by Dalla, was printed by Gonzalo More in 1939 in Paris. It is significant that this publication venture was undertaken independently of Hayter.

In one of Dalla’s compositions we see a young woman kneeling amidst the rubble to cradle her dead infant. She stares at the lifeless, taciturn body of a young boy. His eyes are closed, his head is flopped back and his flaccid arms and legs dangle down inertly. Dalla poignantly puts a spotlight on the human cost of the war by depicting the despair of a single bereaved individual. Mothers grieving for their children appear in further plates, as do soldiers of the International Brigades. The ninth and final engraving may well be a self-portrait, in which case it marks Dalla’s personal and heartfelt identification with the portfolio’s overt condemnation of the civil war.

Husband vs. Hayter

The tenor of all these works on Spain could not be more dissimilar to that of Hayter’s contributions to both Solidarité and Fraternity. His etchings take a vastly different perspective, concentrating on the fracas of the fight, the action of battling itself. What is foregrounded by Hayter is the act of physical violence, as opposed to its consequences or its equally distressing preludes. He presents a quasi grandiloquent and certainly “masculine” take on fighting—muscular figures locked in altercation, severed limbs being flung from the affray, sweeping blows being dealt. Arguably, his scenarii are more swashbuckling than tragic. It could even be said that Hayter’s work is more engrossed in the bravado of its own technical acumen than in forging an appropriate response to its calamitous subject matter.

Dalla’s work has no such ambition. Through her unpretentious traces, she is able modestly to convey her core message—the suffering of ordinary people. Essentially, Dalla Husband brings an emotionally compassionate facet to the repertoire of Atelier 17, in which Hayter plays no part and to which he may well have been oblivious. He certainly never acknowledged the dimension that Dalla had contributed.

References

Essar, Gary, “Dalla Husband: Surrealist,” Winnipeg: Researching Local Art History, 3 November 1989, Universities Art Association of Canada Conference, School of Art, University of Manitoba, 1989.

Dalla Husband, exhibition catalogue, 13 December 1994–12 March 1995 (Winnipeg: Winnipeg Art Gallery, 1995).

Gravure Automatique: Dalla Husband at Atelier 17, exhibition catalogue, 28 May–21 June 2015 (Burnaby: Burnaby Art Gallery, 2015).

Husband, Dalla & Hughes, Langston, Madrid 1937 (Paris: Gonzalo More, 1939).

Weyl, Christina, The Women of Atelier 17: Modernist Printmaking in Midcentury New York (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2019).

Dr. Silvano Levy began his academic career as lecturer at the University of Liverpool. He subsequently held tenured posts at the University of Bath and Keele University, where he was promoted to Senior Lecturer and then to Reader. Levy’s research first focussed on the linguistic and semiotic analysis of art, with articles on words and images, metaphor, hysteria and psychoanalysis. This thread culminated in the major work Decoding Magritte, which argues that the language impairment of aphasia reveals the cryptic mechanism underlying the artist’s oeuvre. In a second line of research, Levy pushes the boundaries of extant knowledge with studies on artists hitherto at the periphery of surrealism, such as Conroy Maddox, Paul Nougé, Toni del Renzio and Sheila Legge. In his new book Mary Wykeham: Surrealist Out of the Shadows, Levy significantly extends the roll call of female surrealists.

Other Art Herstory blog posts you might enjoy:

Sculpture or Suffrage: Alice Morgan Wright, by Jennifer Dasal

Modern Women Artists in Copenhagen 2024–2025: Three Exhibitions, by Alice M. Rudy Price

Frida: Beyond the Myth at the Dallas Museum of Art, by Olivia Turner

A Quiet Eye—The Unique Achievement of Sylvia Shaw Judson, by Rowena Loverance

Deirdre Burnett: A Significant British Ceramic Artist Remembered, by Jo Lloyd

Nancy Sharp: An Undeservedly Forgotten Exemplar of Modern British Painting, by Christopher Fauske

Reflections on the Audacious Art Activist and Trailblazer Augusta Savage, by Sandy Rattley

Women Artists from Savannah at the Telfair Academy Museum, by Julie Allen

The Cheerful Abstractions of Alma Thomas, by Alexandra Kiely

Material Re-Enchantments: A Review of Remedios Varo: Science Fictions, by Suzanne Karr Schmidt

Anna Ancher’s Vaccination and Scientific Motherhood, by Alice Price

Celebrating Eliza Pratt Greatorex, an Irish-American Artist, by Katherine Manthorne

Esther Pressoir: Imagining the Modern Woman, by Suzanne Scanlan

Anna Boberg: Artist, Wife, Polar Explorer, by Isabelle Gapp

The Life and Art of Dorothea Tanning, by Victoria Carruthers

The Abstract-Impressionism of Berthe Morisot and Joan Mitchell, by Paula Butterfield

The Ongoing Revival of Matilda Browne, American Impressionist, by Alexandra Kiely

The Theatrical Wonders of Jeanne Paquin’s Belle Époque Parisienne, by Julia Westerman

Eunice Golden: Making Space for Female Eroticism in the Art Institution, by Isabel Gilmour

Do We Have Any Great Women Artists Yet? by Sheila ffolliott

The Politics of Exhibiting Female Old Masters, by Sheila Barker

I am the niece of Dalla Husband, born 1937 in Vernon, B.C. I repatriated a large painting by Dalla from a Paris Gallery. I loaned it to the Winnipeg Gallery for the Exhibition in 1995. It was the year I met Sister Mary Wykeham, a friend of my Aunt when they were artists in Paris. I am so surprised to learn of her accomplishments. I was only 7 when she died in Mexico. I am now living in Bedford, Nova Scotia

Hi June. Could you post a photo of her? I just read of her collaboration with Langston Hughes and am dying to know what she looked like.

Hi June, I am the author on the book on Mary Wykeham and would be fascinated to hear more about your meeting with Mary. I would also be glad to see the work by Dalla that you have.

Kind regards, Silvano

PS I’m on Facebook