Guest post by Isabel Gilmour, Bachelor of Arts Candidate in Art History, Columbia University

The unabashed and open expression of one’s sexual desire is still taboo in American society. But with her male landscapes that communicate her erotic desire for the male body, artist Eunice Golden envisions a world in which expressions of female sexuality are normalized. At 93 years old, Golden continues to express erotic yearning for the male body in the age of the Anthropocene. Her current exhibition at SAPAR Contemporary, entitled Eunice Golden: Metamorphosis, speaks to her continued exploration of female sexuality.

Background

The New York School, a distinctively North American conglomeration of American artists that emerged from the rubble of the Second World War, asserted the importance of the United States in the art world. Artists such as Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko demanded the world’s attention with large canvases that enveloped viewers in their even larger egos. Dismantling European painting traditions, these artists reimagined calculated brush strokes and employed their whole bodies in a technique they called “action painting.” Abstract Expressionism was inextricably linked to performative displays of masculinity. As a result, women artists were present but largely unrecognized in this artistic movement.

In the 1960s and ‘70s, however, oppressed social groups in the United States began fighting for civil liberties possessed at the time only by white American men. Second Wave Feminists brought to the forefront of American politics the discrimination they faced in all realms of life. Under the leadership of women like Gloria Steinem and Betty Friedan, the Second Wave Feminist movement rejected the exclusion of women from the public sphere and protested their subjugation in the home. This activism led women artists to criticize art institutions that had long overlooked their contributions to art history; Eunice Golden was one of these women.

Eunice Golden’s unlikely path to art

Born in 1927 in Brooklyn, New York, Eunice Golden followed to a tee American cultural expectations for women. Marrying, settling down in the suburbs, and raising children, however, Golden felt confined in her role as a suburban-housewife. In experimenting with art, she was not content to create portraits of domestic bliss. Golden depicted instead the object of her own erotic desire: the male body. Through working on papers that rivaled the size of the enormous canvases of Pollock and Rothko, Golden demanded space for expression of female erotic desire in the New York art scene.

After years of developing her own creative practice, Golden enrolled in and graduated from the Fine Arts program at SUNY, Empire State College, New York in 1978. She later earned her Master of Fine Arts degree from Brooklyn College, New York, in 1980. Her works have featured in exhibitions in arts institutions around the world, including SoHo 20 (the women artists’ cooperative gallery, where she was a cofounding member in 1973), the Whitney Museum, the Brooklyn Museum, and most recently in the Stadtgalerie Saarbrücken.

Fighting Censorship

The censorship of nude male bodies in the works of women artists was not new; nor was it a uniquely American phenomenon. Men artists have celebrated and objectified the female body in art for centuries. But as recently as the eighteenth century, women artists working in Europe were forbidden from studying the nude male form in life study classes. Men artists, eager to protect their status as history painters, excluded women from their ranks. Citing women’s natural intellectual inferiority, these men encouraged women artists to instead paint genres considered less prestigious, such as still-lifes.

Women were systemically excluded from the membership of the French and British royal academies–Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture and the Royal Academy of Arts respectively. There were exceptions for extraordinarily talented women such as Angelica Kauffman and Élisabeth Vigée Lebrun whose fathers imparted their artistic craft upon their daughters. Even these women, however, struggled to be recognized for their artistic prowess. They had to navigate the complicated relationship between flaunting their incredible skills and maintaining modest, feminine personas.

20th-Century Women Artists and Eunice Golden’s Works

The patriarchal attitude of eighteenth-century men artists lingered long after the focus of the art world shifted from Paris to New York after World War II. The relative invisibility of female erotic desire in the art world inspired Golden brazenly to depict her own desire through painting. Driven by a need to demystify female sexuality and the male nude, Golden created works such as Rape #2 (1973) and Landscape #160 (1972). Abstract Expressionists like Willem de Kooning created grotesque defacements of the female nude, but few men artists were as interested in exploring the implications and potential eroticism of the male nude as Golden was. Her desires are not abstract, disguised in amorphous shapes lacking in meaning. They are tangible and tactile. The audience needs not to engage with complex theoretical literature to understand Golden’s yearning for the male body.

In Dreamscape #9, Golden depicts a nude, sexually-aroused man in psychedelic colors. By paying little attention to the model’s face and endowing his phallus with ochre pubic hair, Golden calls attention to his sex organs and renders the identity of her model completely anonymous and irrelevant. His name completely absent from the title, Golden files the memory of his body away and serializes him as one of many compositions. Any viewer can project their own desired partner onto the otherworldly body Golden eroticizes. In this way, Golden mimics the historical idealization of the female nude by men painters who strip their models of their uniqueness.

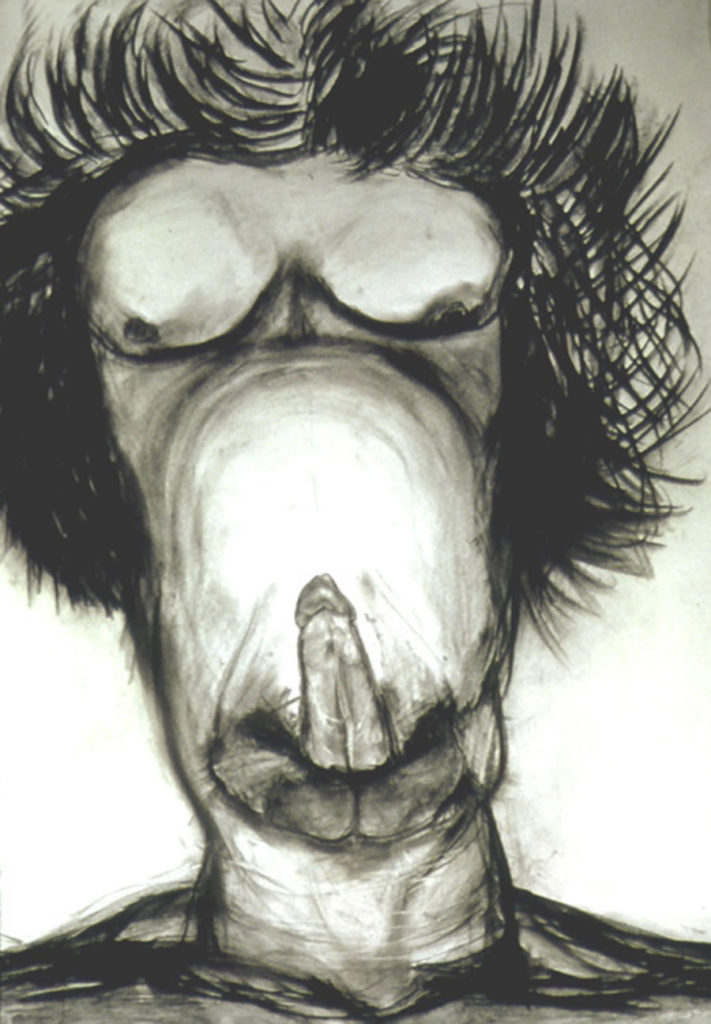

While Dreamscape #9 is undeniably lusty, as the phallus’s bright coloration draws the viewer’s gaze immediately, Rape #2 is more complex in exploring the relationship between the phallus, representative of the ills of patriarchal society, and aconcurrent desire for the male body. Aggressive and violent, Golden renders the male torso like a demonic face capable of lethal violence. It is the male-dominated art institution that rejects Golden’s valuable contributions, that strips Golden of her self-worth and confidence in her works. The work’s title could refer to the societal deprivation of women’s rights.

Commitment to Fighting Censorship

Golden joined the Ad Hoc Women Artists’ Committee in 1970, an organization dedicated to protesting the continued exclusion of women artists’ works from the gallery spaces of New York’s cultural cornerstones. Alongside artists and curators such as Faith Ringgold and Lucy R. Lippard, the Committee responded to institutional gatekeeping and discrimination through sit ins and other demonstrations.

The Committee notably also sent letters to prominent arts organizations in New York City demanding the inclusion of women artists, including artists of color, in arts exhibitions. While institutions like the Whitney Museum failed to feature fifty women artists out of the total one hundred showcased in their 1970 Sculpture Annual, the museum featured twenty—a small step in the right direction. Notably, in their 2010 Biennial, the Whitney Museum included the works of many women artists associated with the Ad Hoc Women Artists’ Committee, finally acknowledging the contributions of feminist artists in efforts to make institutions more inclusive.

While certain institutions responded to the demands of women artists, institutional discrimination was deeply entrenched and difficult to eradicate completely. Censorship of Golden’s works continued and, in 1973, Golden was invited by Anita Steckel to join the Fight Censorship group with artists Louise Bourgeois, Martha Edelheit, Joan Semmel, Juanita McNeely, Anne Sharp, Joan Glueckman, and Hannah Wilke.

Currently on Display at SAPAR Contemporary – Eunice Golden: Metamorphosis

Golden continues to flip the artistic trope of the female nude on its head through her male landscapes. Her current exhibition at SAPAR Contemporary in Tribeca, New York City, continues to explore female sexuality in the age of the Anthropocene. Golden offered on her recent series, Metamorphosis, that through expressing her physiological and psychological desires, she operates “where there are no boundaries and where natural phenomena are blurred by processes of metamorphosis.” In other words, Golden’s erotic fantasies allow her to explore ambiguity; from curving and tactile tree branches she is able to imagine sexed beings.

Metamorphosis #16 anthropomorphizes flora, imagining tree branches to be male torsos, the phallus transposed onto a curving black branch that protrudes from another. Though Golden’s lust is perhaps disguised in these less direct expressions of female erotic desire, her choice to render branches like bodies shows her pervasive fantasization of the male body. Golden, through her Metamorphosis series, normalizes female erotic desire and challenges artistic tropes dictating the traditional symbolic association between women and the natural world by likening men to tree branches and other plants.

The Significance of Eunice Golden

Golden’s works celebrate unabashed female desire for the male body and, for this reason, are revolutionary in American feminist art. Though her contemporaries Louise Bourgeois and Carolee Schneemann are better remembered and documented for their similarly controversial paintings, sculptures, and in Schneemann’s case performances, Golden’s works also communicate the triumphs of women artists. By returning to figuration, Golden directly challenges the abstract methods of artmaking popularized by her male counterparts–and thus challenges their domination of the American artistic narrative.

Eunice Golden: Metamorphosis, curated by Aliza Edelman, is on view at SAPAR Contemporary through November 28, 2020 at 9 N. Moore St. New York, NY 10013.

Isabel Gilmour is currently an undergraduate student at Columbia University in the City of New York, studying art history.

If you liked this Art Herstory guest blog post, you might also enjoy:

Dalla Husband’s Contribution to Atelier 17, by Silvano Levy

Anna Boberg: Artist, Wife, Polar Explorer, by Isabelle Gapp

Happy Birthday, Fidelia Bridges! by Katherine Manthorne

Esther Pressoir: Imagining the Modern Woman, by Suzanne Scanlan

The Life and Art of Dorothea Tanning, by Victoria Carruthers

Do We Have Any Great Women Artists Yet? by Sheila ffolliott

The Politics of Exhibiting Female Old Masters, by Sheila Barker

Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists, by Elizabeth Sutton

Victorine Meurent, More than a Model, by Drēma Drudge

The Abstract-Impressionism of Berthe Morisot and Joan Mitchell, by Paula Butterfield

The Theatrical Wonders of Jeanne Paquin’s Belle Époque Parisienne, by Julia Westerman