Guest post by Patricia Rocco, Hunter College, CUNY

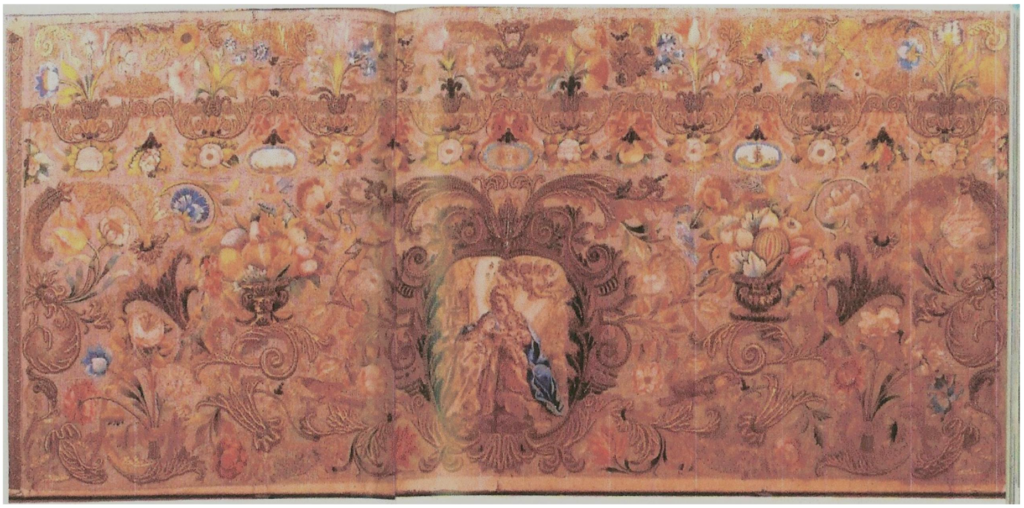

Although Lavinia Fontana and Elisabetta Sirani worked with paint rather than textiles, nevertheless their work intersected with Bologna’s thriving embroidery industry in the sixteenth and seventeenth century. Scholars often fail to give textiles (such as Figure 1) their due importance in art history in terms of the analysis of religious iconography, patronage, and reception studies.

In Bologna, however, young women worked in convents and conservatori, copying famous paintings of local artists, including those by women. The subject matter displayed the gendered iconography of Counter-Reformation models of feminine virtue as adapted for the use of the young girls living and working in these charitable Christian reform houses. Bolognese noblewomen or wealthy silk merchants commissioned visual imagery for these sites based on the church’s call for a maniera devota (devout manner) in sacred painting. This post examines how two such paintings by Fontana and Sirani became part of an important dialogue in the production of sacred visual culture between the maniera devota and the mano donnesca, or womanly hand.

Why Bologna?

The city of Bologna had an unprecedented large group of active women artists due to various factors, not least of which is the fact that it was a crucial site of Catholic reform after the Counter-Reformation. The city’s tireless reformer, the Archbishop Gabriele Paleotti (1522–97) wrote the definitive work on the reformation of images; he published the Discourse on Sacred and Profane Images in 1582. The Discorso was a mandate for artists to create clear visual imagery with a didactic purpose, promoting naturalism in reaction to the excessive ornamentation of the mannerist style (see Figures 2 and 3 for examples of Counter-Reformation art). In addition to contributions from the university’s scholars and scientists, Paleotti also called for women’s participation in religious reform. He thus endowed women in Bologna with greater agency than elsewhere, and facilitated the emergence of a successful group of women artists involved in various media, including painting, sculpture, print—and especially, embroidery.

Charitable organizations for the protection of young women’s honour flourished in the city by the sixteenth century. These institutions, which both merchants and the noblemen and women of the city patronized, were known as conservatori. They reinforced the reform efforts of the Council of Trent, and created sites that required their own uniquely tailored imagery, created for—and often by—the women of the city. Both Fontana and Sirani created religious paintings as part of the church’s visual campaign, and pious “womanly hands” then reproduced these images in embroidery for the conservatorio.

Conserving Virtue: Embroidery and the Social History of the Conservatori

The conservatori are important sites of religious imagery, often displaying the gendered iconography of Counter-Reformation models of virtue as adapted for the women living and working there. The very name of these institutions comes from the city’s intent to preserve the girls’ honour. A virtuous form of work, embroidery was the ideal way to occupy idle young hands in a pious fashion. The church saw women’s hands as most appropriate for the delicate work of embroidery. In the environment of the conservatori, the act of embroidery itself also became a vehicle for meditation, in line with its function as a virtuous task. The girls at the conservatori believed that they could maintain and restore their virtue through their prayers and pious handiwork.

One important institution for the poor was the Opera dei Poveri Vergognosi started in 1495 and dedicated to St. Nicholas, patron of wayward girls. By 1554 it was annexed to another charitable group especially for women, the Putte di Santa Marta, the site for the following images.

The Iconography of Women’s Virtue

The iconography of the religious imagery at these sites intrinsically relates to their function. Subjects such as Martha and Mary, St. Nicholas, the Sewing Madonna, and other holy Mother and Child imagery had special resonance with the audience of these images. The Conservatorio of the Putte di Santa Marta needed religious imagery that would illustrate the appropriate Christian behaviour for the virgins living therein. Two of these images are Lavinia Fontana’s Christ in the House of Martha and Mary (Figure 4), and her seventeenth-century successor Elisabetta Sirani’s Madonna and Child with St. Joseph and Teresa (Figure 5). Fontana executed her painting for the chapel of the Putte di Santa Marta; it is miraculously still in its original location. In 1678 her biographer Carlo Cesare Malvasia writes that this work served as the model for the embroidered copy at Santa Marta.

Sirani’s painting was commissioned for a local silk merchant and then translated into embroidery by the putte with some modifications. Unfortunately, Napoleon’s suppression of the orders in the 1790s caused tragic disruptions to religious life and many of these paintings and their archives are now lost. These paintings are particularly important for the study of women and the Counter-Reformation because they were re-created in embroidery by the virgins themselves, thus passing from one mano donnesca to another.

Lavinia Fontana and the Devout Style

By way of a brief introduction to her work, Lavinia Fontana’s (1552–1614) career marks the emergence of women artists during a complex period that is often misguidedly subsumed under the monolithic title of Mannerism. Fontana’s fame in her own day was such that Paleotti himself gave her the commission for an altarpiece of the Assumption for his own chapel in San Pietro. We can already sense her command of her craft in an early self-portrait, created for her fiancée (Figure 6).

For the young inhabitants of Santa Marta, Fontana’s painting of Martha and Mary is unique as a document that carries traces of collaboration between generations of women and the manifestation of their piety. The work is partly influenced by the style of her father, Prospero Fontana. However, Lavinia goes beyond her father’s characterizations when it comes to the female figures. Martha and Mary are shown as two young ladies (Mary seems the younger of the two), who may have been intended as role models for the viewers of this painting. In Counter-Reformation iconography, Martha and Mary respectively represent the active and contemplative life, a perfect set of role models for young women in the conservatorio whose lives would have mirrored these two spheres of devotion: pious work and pious thought.

Elisabetta Sirani and the Womanly Hands

Lavinia’s heir was the seventeenth-century Bolognese painter Elisabetta Sirani (1638–1665). She executed this self-portrait in the grand style, surrounded by her collection of important books and classical sculptures (Figure 7).

Sirani painted for only a short period—ten years or so—yet produced over 200 paintings, drawings, and etchings. She was noted for her pious Madonnas in the style of Guido Reni, with whom her father had worked, categorized as Bolognese classicism. Sirani was also famous for her school of painting, one of the first of its kind, of which many students were young women of Bologna.

Sirani’s work continued the rapport between the women of the city, visual imagery, and the convents and houses of reform. She created a Madonna and Child with Saints Joseph and Teresa for the silk merchant Rizzardi; it was this painting that the putte of Santa Marta copied in embroidery (Figures 5 and 6). However, rather than create a straight copy, the girls of the institution appropriated Sirani’s image with a few relevant changes. St. Joseph was eliminated and St. Martha, who was the patron saint of the reform institution, was substituted for St. Teresa. (St. Martha was a role model for the girls, as was Mary Magdalene.)

Thus the girls in the institution personalized the artist’s painting, creating a site-specific version using their patron in an example of textual and iconographic appropriation. In this way they fashioned a more intimate sacra conversazione (an image where the patron dialogues with the sacred figure) between the Madonna and Child and their patron saint.

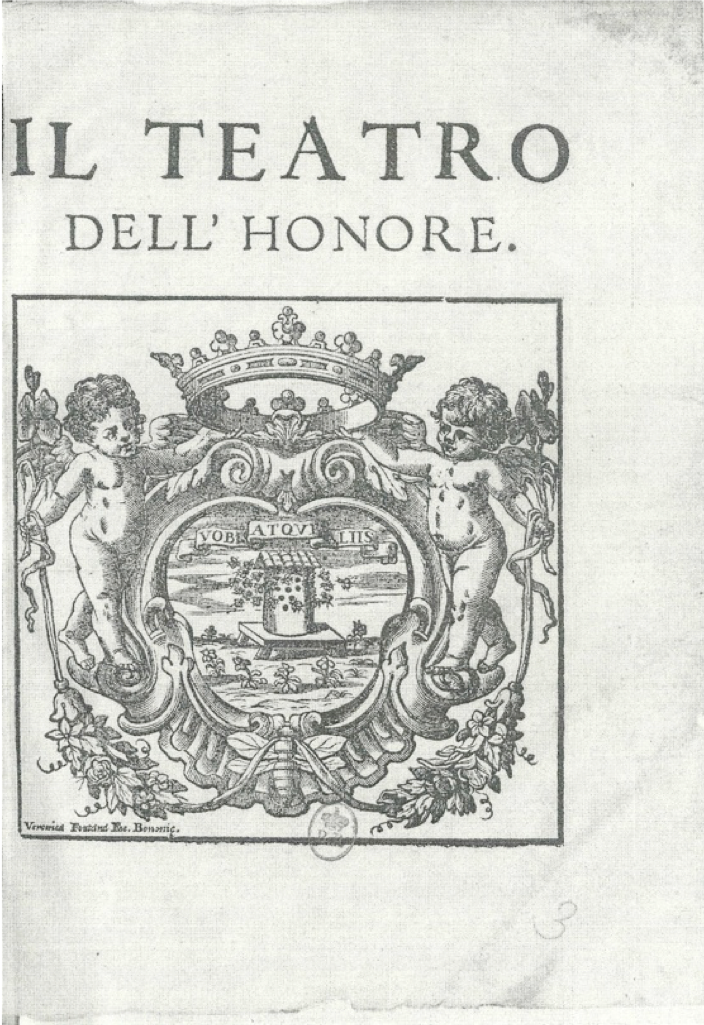

In addition, the framing device is very similar to that used in book illustration, for frontispieces. More specifically, the embroidery of Sirani’s painting is framed in an almost identical fashion to the frontispiece woodcut for the volume Teatro dell’Honore from Parma by Veronica Fontana, one of Elisabetta Sirani’s students (Figure 8).

Veronica Fontana set the image within a border created by the same type of decorative scroll device. Since the girls often worked from a print copy of the original painting, this addition is a further level of appropriation. Their repetition of this framing motif, originally found in books, in the medium of embroidery gives evidence of the close connection between these different media during the seventeenth century, as well as of the possible collaboration between the women artists of the city.

Conclusion: the Embroidery and the Ecstasy

The last piece of the puzzle is the reception of the embroidered imagery, including its use as a meditative tool in the daily rituals of women’s hands. The Council of Trent encouraged the communal pious work of embroidery, and thus instituted a direct relationship between work and prayer in the task of embroidery. The writings of nuns from the period provide written evidence for these practices. For example, Diomira del Verbo Incarnato, from the convent of Fanano, supposedly went into religious ecstasy while working on the loom. She stated that “this work, because of its beauty and nobility, raised my spirit to contemplate the beauties of my God.”

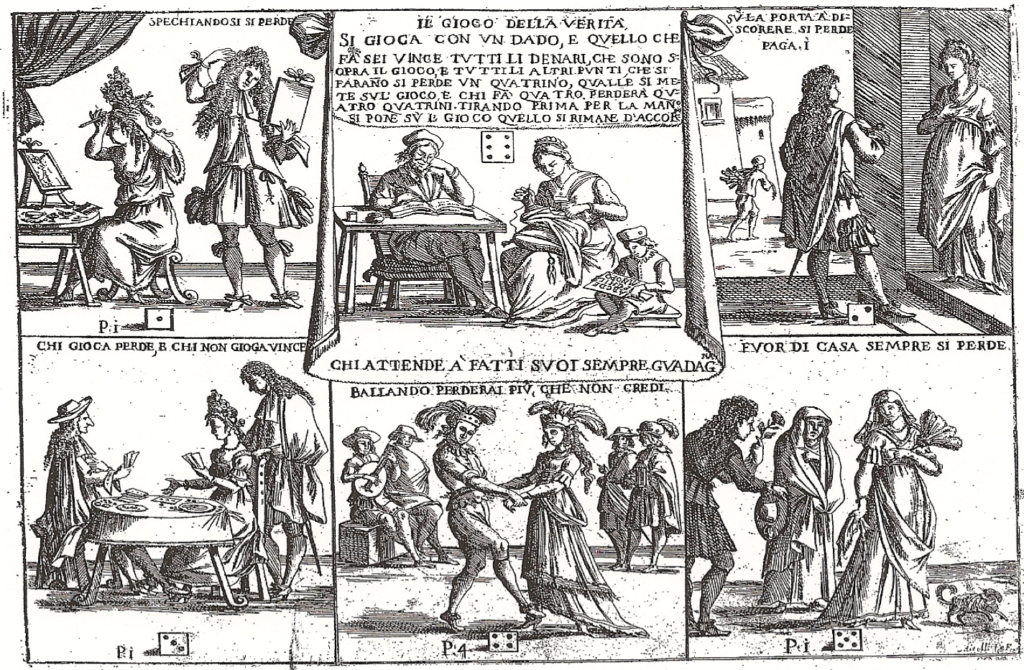

The visual culture of women’s work in the conservatorio, both literally and figuratively, had a hand in constructing its own models of sanctity. These sites became places where women could weave a sacred tapestry of feminine virtue. A final image serves as an example of how these Counter-Reformatory role models persisted long into the seventeenth century and beyond. Figure 9 is an etching of a game print by Giuseppe Maria Mitelli, the prolific Bolognese engraver of the city’s social mores. These boardgames were meant to be played with dice, but also had a moralistic meaning. In this example, the Game of Truth, the winning box shows the correct behaviour for pious young women, at the center we have a dutiful housewife engaged in the task of embroidery, still dutifully stitching her way to virtue.

Patricia Rocco received her PhD from the Graduate Center, CUNY, and is an Adjunct Professor of Art History at Hunter College, Manhattan School of Music, and Cooper Union. She has published articles on women artists, gender, and material culture, especially women’s work with textiles. Her book The Devout Hand: Women, Virtue, and Visual Culture in Early Modern Italy has recently been published by McGill-Queen’s University Press. Rocco has also published two chapters on popular prints and games in the early modern world: “Virtuous Vices: Giuseppe Maria Mitelli’s Gambling Prints and the Social Mapping of Leisure and Gender in Post-Tridentine Bologna,” in Playthings in Early Modernity, and “The World Upside Down: Giuseppe Maria Mitelli’s Games and the Performance of Identity in the Early Modern World,” in Games and Game Playing in Early Modern Art and Literature.

More Art Herstory guest posts about Bolognese women artists:

Elisabetta Sirani’s Studio Visits as Self-Preservation: Protecting an Artistic Career, by Victor Sande-Aneiros

The Restoration of Royalty: Lavinia Fontana’s Queen of Sheba and King Solomon, by Dr. Aoife Brady

Celebrating Bologna’s Women Artists, by Dr. Babette Bohn

Elisabetta Sirani: Self-Portraits, by Jacqueline Thalmann

Drawings by Bolognese Women Artists at Christ Church, Oxford, by Jacqueline Thalmann

Lavinia Fontana and Elisabetta Sirani at the Smith College Art Museum, by Dr. Danielle Carrabino

Elisabetta Sirani of Bologna (1638–1665), by Dr. Adelina Modesti

Lavinia Fontana: Italy’s First Female Professional Artist, by Dr. Elizabeth Lev

Sister Caterina Vigri (St. Catherine of Bologna) and “Drawing for Devotion,” by Dr. Kathleen G. Arthur

More Art Herstory guest posts about Italian women artists:

Plautilla Nelli and the Workshop of Santa Caterina in Cafaggio, by Alessia Motti

Female Solidarity in Paintings of Judith and her Maidservant by Italian Women Artists, by Sivan Maoz

Plautilla Nelli and the Restoration of her Altarpiece Madonna del Rosario. by Jane Adams

Judith’s Challenge, from Lavinia Fontana to Artemisia Gentileschi, by Alessandra Masu

Thoughts on By Her Hand, the Hartford Iteration, by Erika Gaffney

Plautilla Bricci: A Painter & “Architettrice” in Seventeenth-century Rome, by Alessandra Masu

Giovanna Garzoni’s Portrait of Zaga Christ (Ṣägga Krǝstos), by Alexandra Letvin

By Her Hand: Personal Thoughts and Reflections on an Exhibition, by Oliver Tostmann

Sister Eufrasia Burlamacchi (Lucca, 1478–1548), by Dr. Loretta Vandi

Artemisia Gentileschi: What Wasn’t in the London Exhibition and Why it Matters, by Jesse Locker

“La grandezza del universo” nell’arte di Giovanna Garzoni / “The grandeur of the universe” in the art of Giovanna Garzoni, by Sara Matthews-Grieco

Plautilla Bricci (1616–1705): A Talented Woman Architect in Baroque Rome, by Consuelo Lollobrigida

Renaissance Women Painting Themselves, by Katherine McIver

Orsola Maddalena Caccia (1596–1676), Convent Artist, by Angela Ghirardi

Two of a Kind: Giovanna Garzoni and Artemisia Gentileschi, by Mary D. Garrard

The Priceless Legacy of Artemisia Gentileschi: A Curator’s Perspective, by Judith W. Mann

Trackbacks/Pingbacks