Guest post by Kathleen E. Kennedy, Associate Professor, Centre for Medieval Studies, University of Bristol

Susanna Horenbout (c. 1500–c. 1554) remains a shadowy figure for one simple reason: she was a woman. The daughter of the famous artist, Gerard Horenbout, she was probably born in Ghent, and trained as an artist in her father’s workshop. At some point in the 1520s, Susanna, her brother Lucas, and her father and mother all moved to England, where they lived and worked for the rest of their lives.

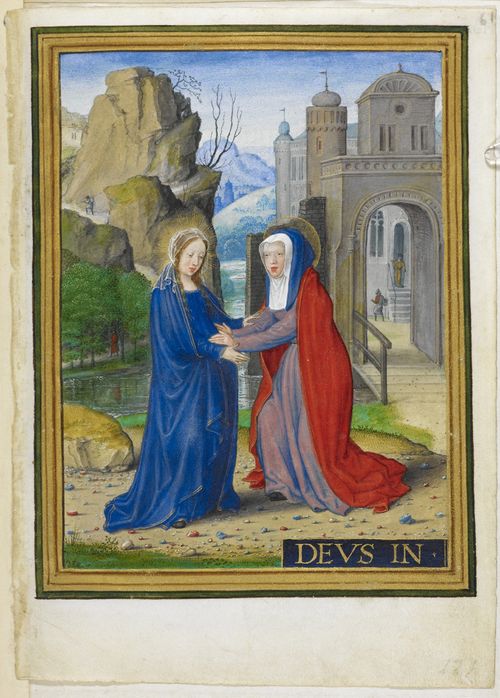

Susanna’s father, Gerard Horenbout, served both Margaret of Austria (who ruled in the Netherlands) and Henry VIII of England as a court artist. Perfecting the Flemish style of the Northern Renaissance, Gerard also adopted Italianate influences. Now identified as the Master of James IV of Scotland, Gerard can be connected to only one extant project through archival documentation: a selection of illuminations in the Sforza Hours made for Margaret. Artistically very close to the Sforza Hours are two illuminations completed for the English Percy family in a copy of John Lydgate’s Troy Book. But what was Gerard’s actual role? While there is no question that Gerard worked on the Sforza Hours, most critics also believe members of his workshop painted parts of these images, too. Despite their fame, today we cannot tell the work of Susanna, Lucas, or Gerard apart.

Artist

Albrecht Dürer purchased an image of Christ from Susanna in 1521, before she moved to England. He wrote of his wonder that a woman had painted it: “It is very wonderful that a woman’s picture should be so good (Ist ein gross Wunder, das ein Weibsbild also viel machen soll).” Yet, the great artist made several journeys to Italy, where we now know that women artists achieved contemporary fame. An explanation for Dürer’s surprise may lie in his own history. Dürer had already been well-known as an artist when not much older than Susanna. It’s possible that Dürer was less struck by Susanna’s gender than by her well-developed craft at such a young age. He knew precisely what that kind of skill required.

If Susanna was already an accomplished artist in 1521, she must have taken part in the illumination of the Sforza Hours. We must learn to read art criticism against the grain. When Gerard is mentioned painting these images, we must be willing to replace his name with Susanna’s. Comments like “the sixteen miniatures added to the Italian books by Horenbout are among the most beautiful in sixteenth-century Flemish illumination, the work of an artist of the first rank” can refer to Susanna’s work (Kren and McKendrick, 429). Likewise Susanna “Horenbout often gave [traditional iconography] new meaning and freshness” as did also her brother and father (Kren and McKendrick, 429).

We don’t know precisely how the Horenbout family arrived in England. Did they travel together, or emigrate one by one? We know that Lucas was in England by 1525, and Gerard by 1528. Gerard’s wife, and Lucas’ and Susanna’s mother, Margaret, died in England in 1529. Her mother’s death provides the earliest English record we have of Susanna, as she is named on her mother’s remarkable mortuary brass. Susanna buried her mother in All Saints, Fulham, the parish in which she and her husband John Parker resided.

Courtier

Therefore, Susanna must have arrived in England some time between 1521 and 1529. She then quickly met and married the Keeper of Westminster Palace and Yeoman of the Wardrobe, Parker. Susanna surfaces again in the historical record receiving New Year’s gifts from Henry VIII. She served in the welcoming train of Anne of Cleves, who hired Susanna as a gentlewoman of the Privy Chamber. A few years later, Susanna entered Catherine Parr’s household, and she may also have been attached to the household of Princess Mary. Susanna was able to successfully navigate the turbulent waters of the households of at least two of Henry’s wives. She maintained court connections before, during, and after these posts. Such an astonishingly successful career is no small testament to her savvy. Does this ability enable us to say anything about her skill as an artist, however?

What if Susanna’s abilities as a courtier developed as a teen while she assisted her father as Margaret of Austria’s court painter? A precocious daughter with exceptional artistic ability could have been an especially useful assistant to Gerard, beyond the usual labor journeyman artists performed in large workshops. Facility in Anne of Cleves’ Dutch language aside, one did not simply accidentally become attached to royal privy chambers. As an immigrant from a skilled artisanal family, however wealthy, Susanna’s marriage into the English gentry is another step that demands explanation. If Susanna arrived in England with courtly skills already in hand, her marriage to a lifelong courtier such as Parker, and her own entry into multiple royal households, forms a complete picture.

Designer?

We may underestimate the range of art produced by English courtiers, and this limits our understanding of early modern women. We take for granted that many courtiers, men and women both, wrote and circulated poetry in the Tudor and Stuart eras. Yet we rarely consider painting as an art that may also have been practiced in courtly circles. Further, while we do associate painting with portrait miniatures, and therefore with jewelry, we seldom consider how painting was also linked to fiber arts such as embroidery. Yet, Flemish artists designed the cartoons used in weaving tapestries. Gerard Horenbout himself designed at least one tapestry, for the Confraternity of St. Barbara in Ghent. Moreover, Gerard also created embroidery designs. While little needlework produced by the women in Tudor royal circles remains extant, we know that this was one of the arts they practiced. Susanna’s design skills may have been in high demand for fine smallwork.

Scribe?

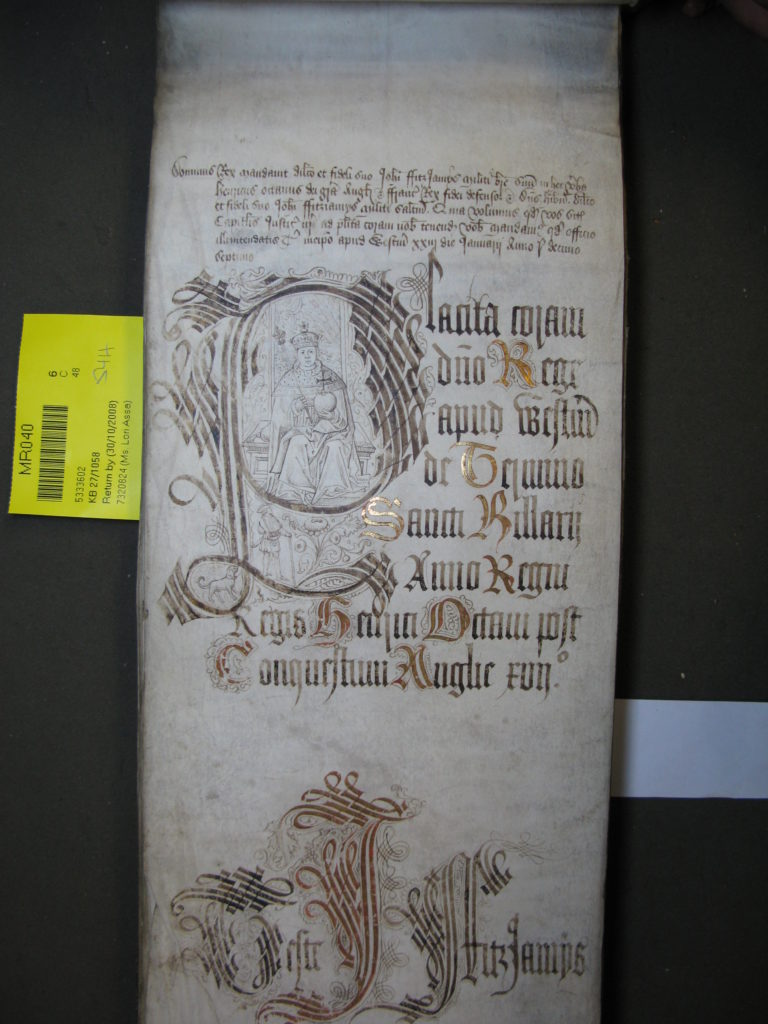

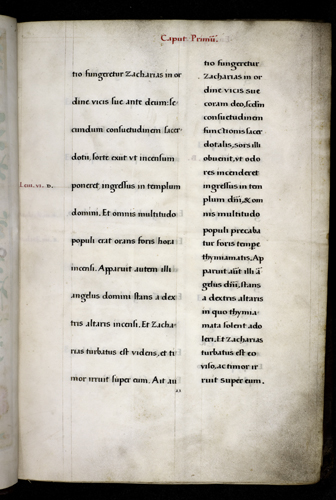

Another overlooked aspect of her father’s skillset may provide even more insight into Susanna’s career: she may have served as a household secretary and scribe. Gerard was not only an artist, but a copyist, paid for his skill at the elaborate texturas and the humanist script increasingly popular for devotional works in the early sixteenth century. Art historians recognize Gerard’s unusual interest in painting incipits directly into his miniatures. This artistic quirk makes more sense when he is viewed as both a fine artist and quality scribe. Margaret of Austria reimbursed Gerard not only for art, but also for script. He hired a copyist for leaves of the Sforza Hours “which he had not had time to write himself” (Campbell and Foister, 720). This account suggests that Horenbout copied part of the Sforza Hours himself.

Script continued to be valued for its aesthetic qualities in the early sixteenth century. Dutch scribe Pieter Meghen famously worked in England for a range of high-profile patrons. His humanist script provides the usual English case study for early Tudor interest in fine handwriting. Meghen collaborated on books with a range of Dutch artists living in England, including the Masters of the Dark Eyes in England, one of the Horenbouts, and Hans Holbein. Susanna Horenbout moved in precisely these circles. Even when decorative script was not needed, nobles commonly employed secretaries, who often served as members of the household. If Susanna had learned to write from her father as she had learned to paint, then this is very likely to have been one of the roles that she filled. We ought then also to examine the papers of these queens’ households and the books that they owned, to see if any individual hands can be distinguished.

A Speculative Conclusion

Susanna’s success as a courtier-artist might be measured by the woman who was arguably her successor in England, Levina Teerlinc. Like Susanna, Levina’s father was a super-star Flemish artist, Simon Bening. Like Susanna, Levina learned her trade in her father’s workshop. Like Susanna, we have no works definitely by Levina, though several portrait miniatures may be her work. Importantly, Levina arrived in England in the mid-1540s, when Susanna served in Queen Catherine Parr’s and possibly Princess Mary’s households. Susanna died in the mid-1550s, while Levina continued to paint and design for Tudor royal and noblewomen into the 1570s. Like Susanna, Levina proved to be a remarkably successful gentlewoman of the privy chamber, serving both Mary I and Elizabeth I. Unlike Susanna, we have records of Levina painting portrait miniatures, as gifts rather than as commissions, for both Mary and Elizabeth.

Susanna’s artistic career must be weighed against her success as a courtier. She may not have been especially prolific in England. Alternately, the art she produced may not have been viewed as important to preserve. Even royal women’s household documents have been less frequently archived than their male counterparts. Over the centuries, scholars have less frequently edited and printed the archives of women than men. Physically fragile, fancy needlework also rarely survives from this period, even when stitched by royals. The possibility of Susanna’s scribal work has so far gone unexplored. Unlike her father, Susanna was not a jobbing artist, and had many other duties. Susanna Horenbout’s oeuvre, or apparent lack of it, may cause more frustration to scholars today than it did to her or to her family in the sixteenth century.

Bibliography:

Janet Backhouse, The Illuminated Page. Ten Centuries of Manuscript Painting in the British Library (British Library, 1997).

Lorne Campbell and Susan Foister, “Gerard, Lucas and Susanna Horenbout,” The Burlington Magazine 128 (1986): 719-27.

Sonja Drimmer, The Art of Allusion: Illuminators and the Making of English Literature, 1403-1476 (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018).

Thomas Kren and Scot McKendrick, Illuminating the Renaissance: The Triumph of Flemish Manuscript Painting in Europe (Getty Publications, 2003).

David Rundle, The Renaissance Reform of the Book and Britain: The English Quattrocento (Cambridge University Press, 2019).

Dr. Kathleen E. Kennedy is Associate Professor in the Centre for Medieval Studies at the University of Bristol, UK. She publishes across a wide range of disciplines. Her last scholarly monograph, The Courtly and Commercial Art of the Wycliffite Bible (Brepols, 2014) is the first monograph to consider the illumination of Wycliffite Bibles at length. She has also prepared the material for a monograph on early Tudor manuscript art and fifteenth-century English engagement with humanism and the Northern Renaissance. Kennedy has two pieces of interest to gender historians forthcoming in 2020, “The Coconut Cup as Material and Media: Extended Ecologies,” about colonial Latin American housewares as media, and an article in the Journal of Jewellery Research, “From Coque de Perle to Osmeña Pearl: A Short Documentary History.”

Other recent Art Herstory guest blog posts:

Finding Catherine Read, by Adam Busciakiewicz

The Lost Works of Susanna Horenbout, Female Artist at the Tudor Court, by Sylvia Barbara Soberton

Susannah Penelope Rosse: Painting for Pleasure in Seventeenth-Century England, by Anna Pratley

A Room of Their Own: Now You See Us Exhibition at Tate Britain, by Kathryn Waters

Mary Beale (1633–1699) and the Hubris of Transcription, by Helen Draper

Anna Maria van Schurman: Brains, Arts and Feminist avant la lettre, by Maryse Dekker

Books, Blooms, Backer: The Life and Work of Catharina Backer, by Nina Reid

“Black-works, white-works, colours all”: Finding Susanna Perwich in her Seventeenth-Century Embroidered Cabinet, by Isabella Rosner

Levina Teerlinc, Illuminator at the Tudor Court, by Louisa Woodville

Paper Portraits: The Self-Fashioning of Esther Inglis, by Georgianna Ziegler

Women Artists of the Dutch Golden Age at the National Museum of Women in the Arts

A Tale of Two Women Painters, exhibition review by Natasha Moura

Gesina ter Borch: Artist, not Amateur, by Nicole E. Cook

Trackbacks/Pingbacks