Guest post by Georgianna Ziegler, Folger Shakespeare Library (Emerita)

The Franco-Scottish calligrapher Esther Inglis (c.1569–1624) is known for her jewel-like manuscripts rendered in meticulous black and white line or in color. But she also created the earliest known self-portrait of a woman artist in Britain. It is possible that miniaturists Susanna Horenbout (c.1500–1554) and Levina Teerlinc (1510–1576), both connected to the English court, painted portraits of themselves, but those have not yet been identified. Calligraphy and limning, or painting in small, were related skills in the sixteenth century, growing out of the tradition of illuminated manuscripts. Both Horenbout and Teerlinc came from families of Flemish illuminators. Esther Inglis, the daughter of French Huguenot refugees to Scotland, was trained by her mother Marie Presot, who was herself a skilled calligrapher. Inglis was initially more influenced by the printed book than the illuminated manuscript tradition, though both played a role in her self-fashioning.

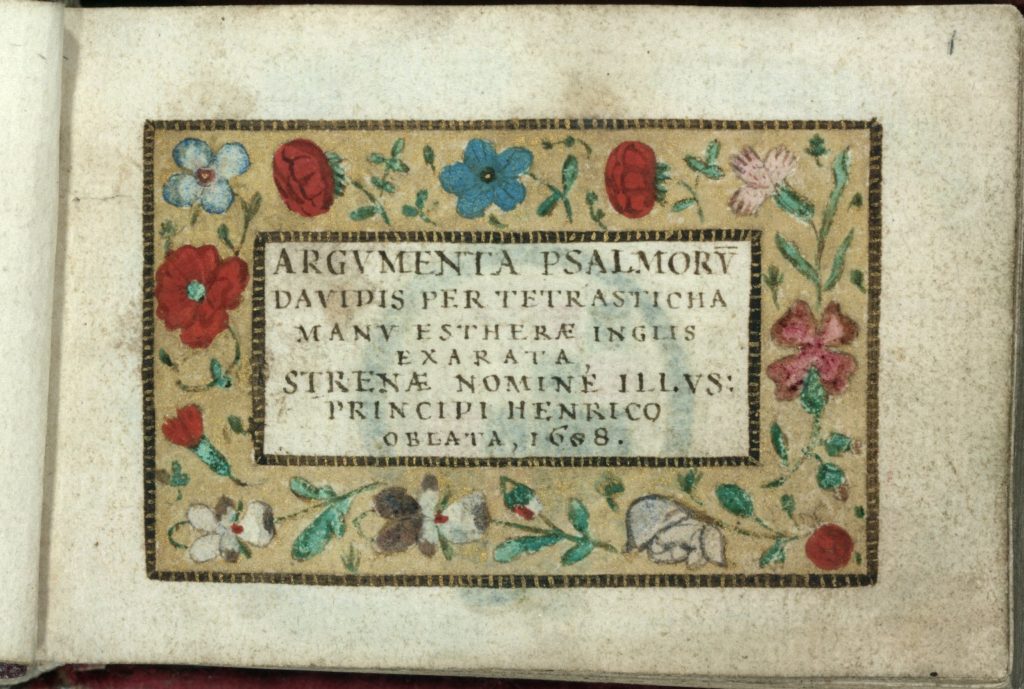

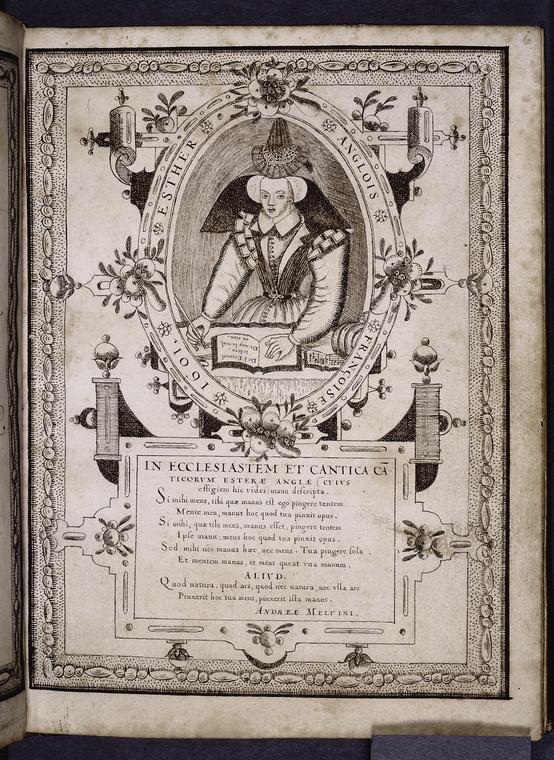

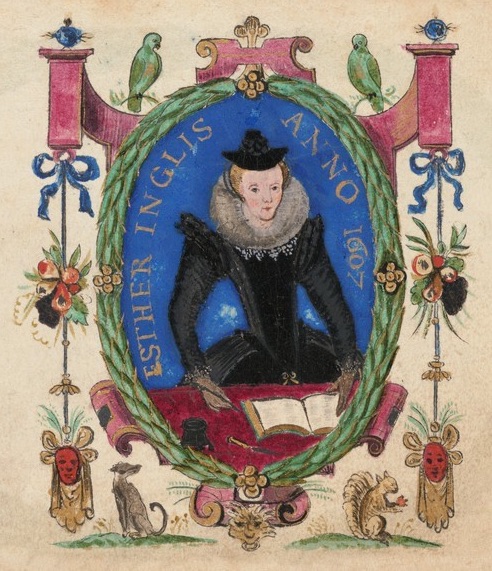

For a time, Inglis worked with her husband, Bartholomew Kello, who was in charge of diplomatic correspondence for James VI of Scotland. Many of her manuscripts were used as part of the diplomatic exchange with those who had influence in the court of Elizabeth I and the wider Protestant movement, including the Queen herself, the Earl of Essex, the Duc de Rohan and Prince Maurice of Nassau. Inglis created her first important group of manuscripts in 1599 when she also began including a self-portrait. Her bibliographers, Scott-Elliot and Yeo, identified four main types of self-portraits, ranging from three-quarter length in black or brown line, or color, to small busts against a blue background. Here I focus on her early line portraits and their relationship to the printed tradition of author portraits.

Inglis’s initial influence was the portrait of Georgette de Montenay which appears in her Emblemes ou divises chrestiennes (Lyons, 1567). Following Alciati and others, Renaissance emblems were generally based on the classical tradition, but Montenay repurposed the genre for Protestant religious instruction. She worked closely with Pierre Woeriot, artist and engraver, who made her portrait and worked with her on the designs for the engravings.

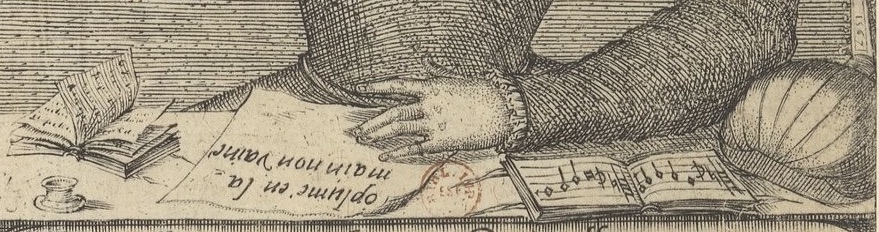

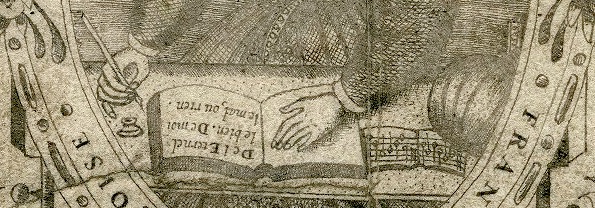

Inglis copied much of Montenay’s book as a gift for Prince Charles in 1624, but as early as 1599 she had been inspired to adopt the iconography of Montenay’s portrait for her own. Following Montenay, Inglis depicts herself at a desk, writing, pen in right hand, a small book held open by her left hand (Montenay uses a sheet of paper). Both show ink wells on the desk and both have a lute and music by their left arm. Both women wear contemporary garb, though Montenay’s brocaded dress denotes her noble family ties and closeness to the court of Jeanne d’Albret, while Inglis’s peaked hat and veil are stylishly middle-class of the period. Montenay’s image has a simple cartouche below with a poem by herself, while Inglis places herself in an elaborate oval frame with laudatory poems by humanist Andrew Melville beneath.

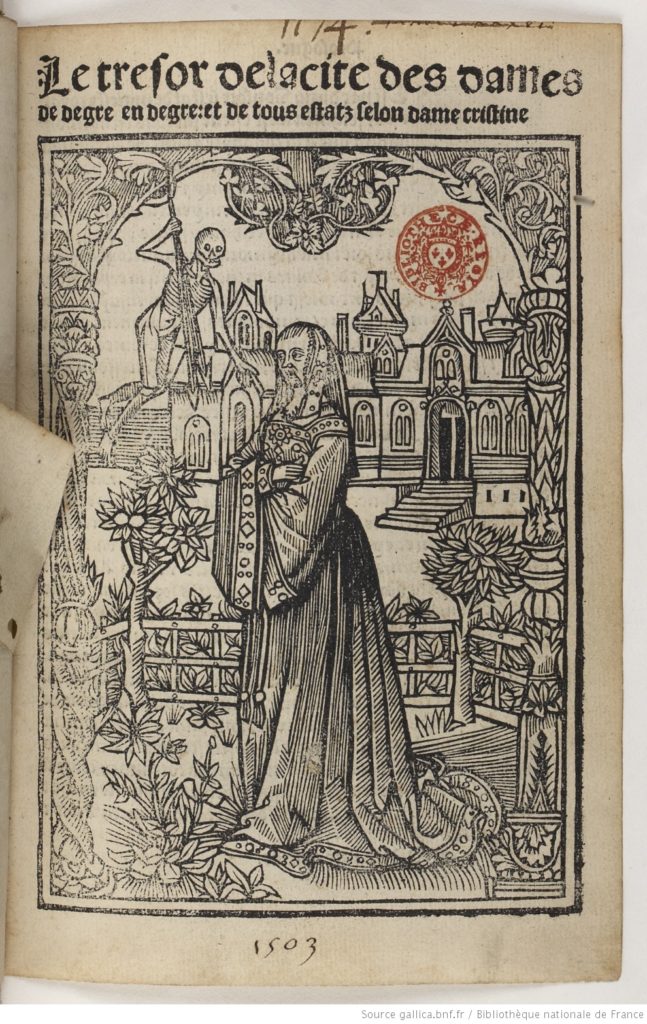

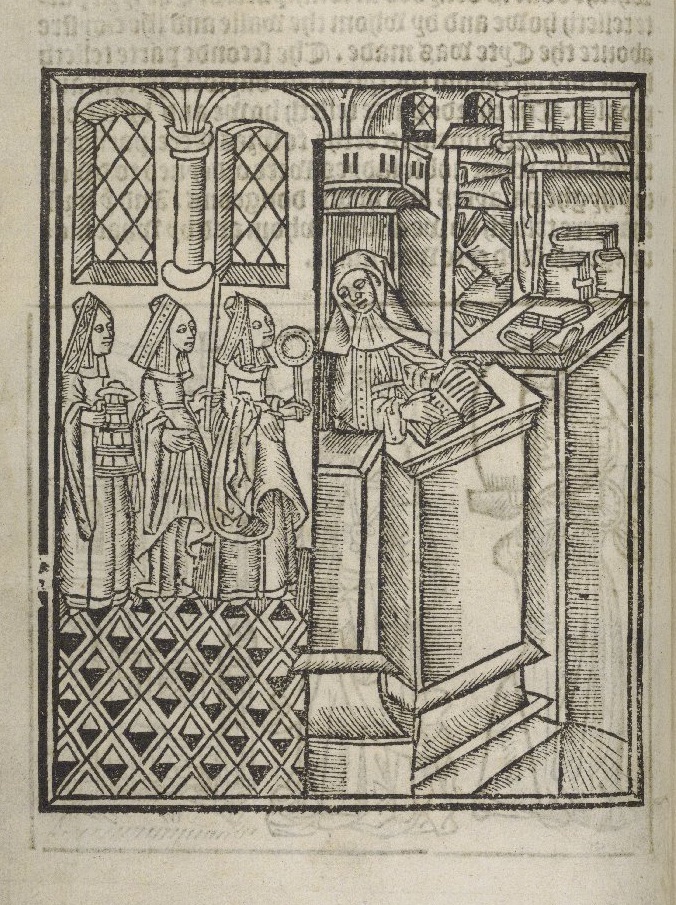

There were few models for depicting women writers, although precursors may be found in the medieval manuscript tradition illustrating works by Marie de France and Christine de Pisan. As far as I have found, Woeriot’s portrait of Montenay is the first in print in France or England to show a recognizable woman writer. Early printed depictions of Christine de Pisan in both France and England fall between what Martha Driver has called “everywoman” and a full-blown portrait study. That is, they are not cuts of anonymous women reproduced in different contexts multiple times, but they are woodcuts showing a generic woman in a garden outside a city (Paris, Le Noir, 1503) and in her study (London, Henry Pepwell, 1521), both meant to represent Christine in editions of The City of Ladies. They are not, however, actual portraits of Christine.

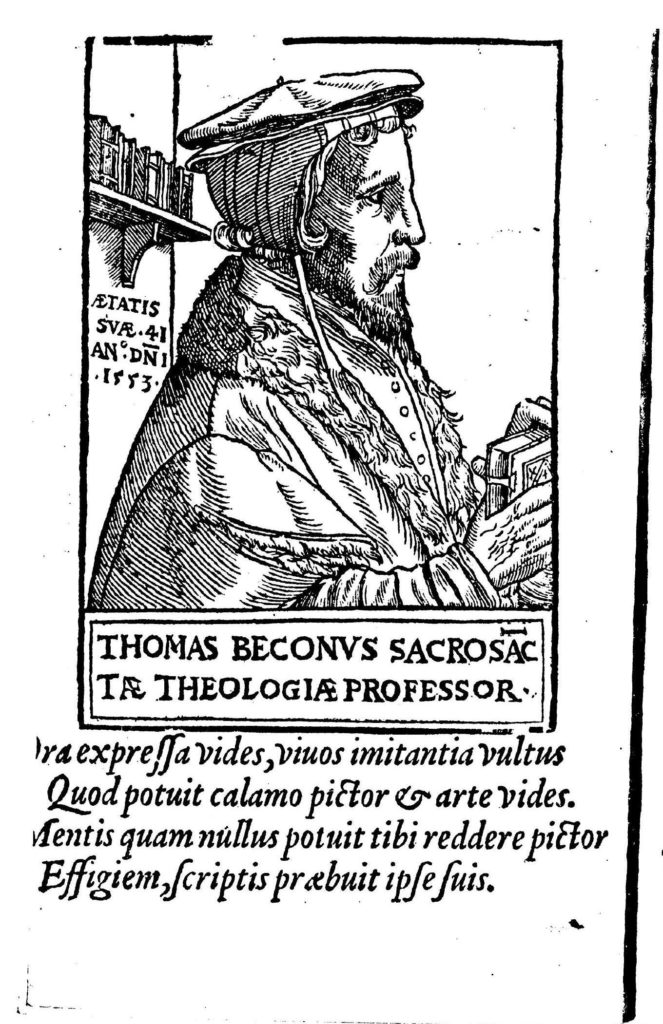

Earlier woodcut portraits of male writers and prominent people of both genders may be profile or full-face, with simple or elaborate frames. One example from 1560 (also used in 1558) is this portrait of Thomas Becon.

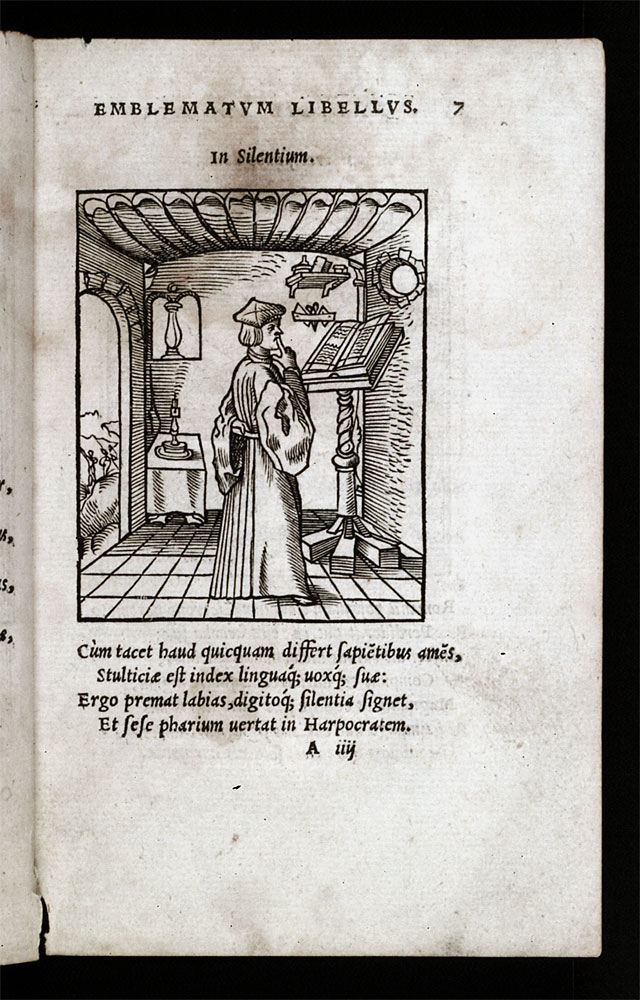

The three-part format—identifier, image, and text—is that used in Montenay’s portrait. It is directly related to the emblem format, dating to at least the early sixteenth century, as seen in this page from the Paris 1534 edition of Alciati’s Emblems.

SMAdd53, Glasgow University Library.

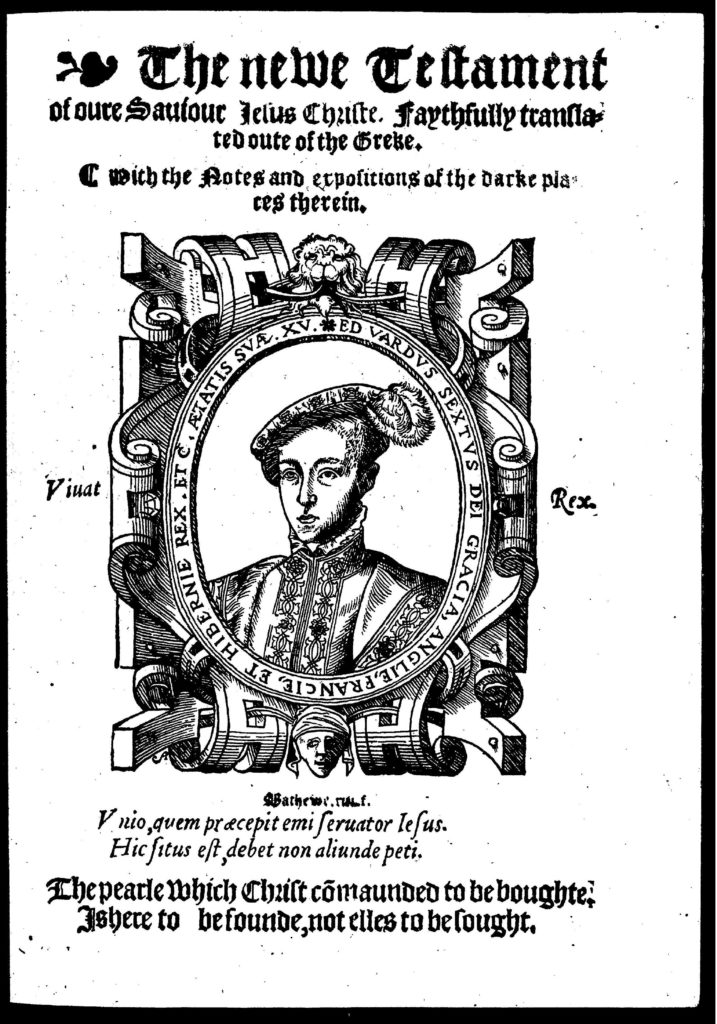

Inglis reworks this basic format for her early self-portraits by using more ornate models, such as the portrait head within an oval frame surrounded by text and a decorative border. An early example is the woodcut portrait of King Edward VI published in 1552.

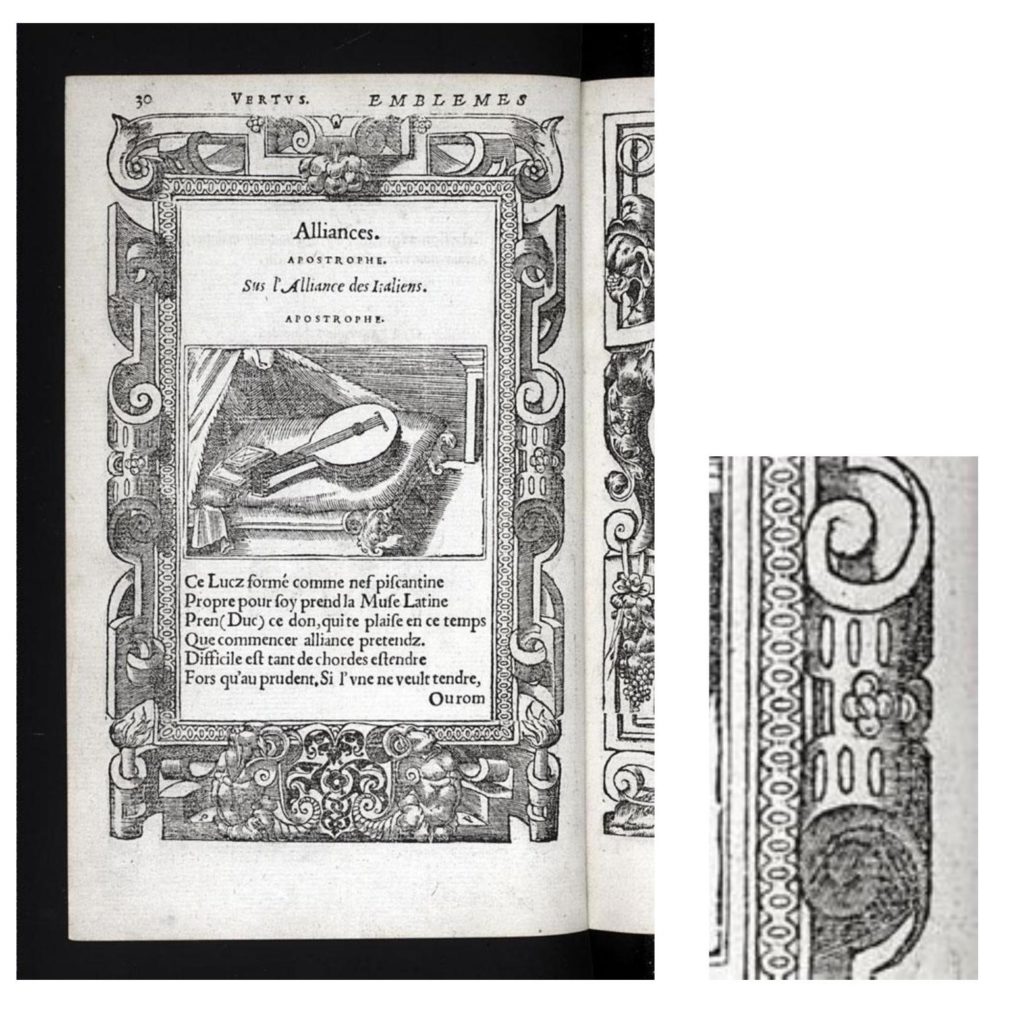

Inglis would have known some of the emblem books by Alciati, such as this one from Lyon, 1549.

Many of her decorative borders were copied from printed books. Indeed, the curled cylinders with piercings shown here are similar to those found in her 1599 self-portrait, while the bunches of fruits and flowers echo those seen here and on other pages.

Why did Woeriot and Montenay include a lute and music in her portrait? They may have been influenced by self-portraits of women artists, though where they would have seen these is unclear. Catharina van Hemessen (1548), Sofonisba Anguissola (c.1556), and Lavinia Fontana (1577)—three of the earliest—all depicted themselves painting and sometimes playing an instrument, or with books (I have given the accepted dates of their earliest self-portraits). Fontana here shows herself at the clavichord, but her easel is visible in the background.

Reading and playing an instrument were skills thought appropriate to women. In his treatise on education (London, 1581), Richard Mulcaster advised that young women learn “‘reading well, writing faire, singing sweete, playing fine,'” and the accepted instruments were keyboard or lute. Women artists, and limners, as Inglis referred to herself, might thus present themselves with music to raise their position from a “mere” artisan to someone skilled in female accomplishments. In choosing to add a lute to their portraits, Montenay and Inglis were showing that putting your poetry into print and engaging in calligraphy were acceptable pursuits for women.

Piety also plays an important role in these portraits. Montenay’s poem beneath her portrait says that with her instrument, books and pen she sings the excellence of God. On the paper in front of her she has written part of the poem which states that the pen in her hand is not in vain because she writes in praise of Christ. In her book, Inglis has written: “De l’Eternal le bien: de moi le mal, ou rien” (“From the Eternal, goodness, from myself, evil, or nothing”; i.e. “all good gifts come from God; of myself, I am nothing”).

These Protestant women write and draw in the service of God. Even more than the lute, dedicating their work to God gives it legitimacy. The attitude of Protestant Reformers to visual imagery was at best reluctant, as they decried the idolatry of images among Catholics. Nevertheless, some of the early Reformers allowed their portraits to be painted, usually book-in-hand, as commemoration of their history and of the importance of the written Word, and these circulated widely in woodcut or engraved copies.

Both Montenay and Inglis appear poised and confident in their portraits. Over the years, Inglis refined and simplified her self-portraits, first taking away the musical references. In this 1606 manuscript made for Thomas Egerton, Lord Chancellor to King James I, Inglis keeps the highly decorative frame which includes ornaments from designs in books, but has discarded the lute.

Along the way, the writing instruments also disappear, and she shows herself in three-quarter length, or focuses just on her face in an oval with a dark blue background. These portraits reflect the style made popular by miniaturists such as Lucas Horenbout, Levina Teerlinc (in works which have been attributed to her), and Nicholas Hilliard. They appear from about 1605 on when she turned to using color in most of her manuscripts. By that time she may have felt assured by the acceptance of her work, which was deployed on the international stage of diplomacy and gift-giving.

In the last year of her life, at the age of fifty-three, she reproduced with modifications the book of Montenay’s emblems for Prince Charles, soon to become Charles I. It is a glorious manuscript in black and white. She copied the portrait of Montenay and then on the next page added once more her own image, seated at a desk, with pen, ink, caliphers and ruler but no music. That’s how she wanted to be remembered—as a talented artist of the pen.

References:

- A.H. Scott-Elliot and Elspeth Yeo, “Calligraphic Manuscripts of Esther Inglis (1571-1624): a Catalogue,” PBSA 84:1 (1990) 18-19.

- Cynthia J. Brown identifies the first printed French portrait of a male author in Maurice Scève, Délie, the 1544 edition of his poems. Poets, Patrons, and Printers: Crisis of Authority in Late Medieval France (Cornell: Cornell UP, 1995), 102.

- Martha W. Driver, Image in Print: Book Illustration in Late Medieval England and its Sources (London: British Library, 2004) 64. I am grateful to a conversation with Anne Coldiron on this subject.

- Linda P. Austern, “‘Sing Againe Syren’: The Female Musician and Sexual Enchantment in Elizabethan Life and Literature,” Renaissance Quarterly, 42:3 (1989) 429, 430.

- Margaret Aston, “Gods, Saints, and Reformers: Portraiture and Protestant England,” in Albion’s Classicism, ed. Lucy Gent (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995) 181-220.

Dr. Georgianna Ziegler is the Louis B. Thalheimer Assoc. Librarian and Head of Reference Emerita at the Folger Shakespeare Library. She has published widely on early modern women in literature and art, and curated major exhibitions at the Folger including: Shakespeare’s Unruly Women; and Elizabeth I: Then and Now (both with catalogs). She wrote the entry on Esther Inglis for The New Biographical Dictionary of Scottish Women (2018), and her essay on Inglis for the digital Routledge Encyclopedia of the Renaissance World is forthcoming. Currently she is working on essays on the self-portraits of Inglis and on the manuscripts Inglis prepared for French Protestants. Visit Georgianna’s website, Esther Inglis (c. 1570–1624): Calligrapher, Artist, Embroiderer, Writer.

More Art Herstory blog posts about women artists who worked in England:

The Lost Works of Susanna Horenbout, Female Artist at the Tudor Court, by Sylvia Barbara Soberton

Susannah Penelope Rosse: Painting for Pleasure in Seventeenth-Century England, by Anna Pratley

A Room of Their Own: Now You See Us Exhibition at Tate Britain, by Kathryn Waters

Angelica Kauffman: Art, Music and Poetry, by Ellice Wu

Mary Linwood’s Balancing Act, by Heidi A. Strobel

Levina Teerlinc, Illuminator at the Tudor Court, by Louisa Woodville

Angelica Kauffmann: Grace and Strength, by Anita V. Sganzerla

Mary Beale (1633–1699) and the Hubris of Transcription, by Helen Draper

“Black-works, white-works, colours all”: Finding Susanna Perwich in her Seventeenth-Century Embroidered Cabinet, by Isabella Rosner

Levina Teerlinc, Illuminator at the Tudor Court, by Louisa Woodville

Susanna Horenbout, Courtier and Artist, by Kathleen E. Kennedy

Angelica Kauffman and Mary Moser: Founding Women Artists of the Royal Academy

‘Bright Souls’: A London Exhibition Celebrating Mary Beale, Joan Carlile, and Anne Killigrew, by Laura Gowing

Other Art Herstory blog posts you might enjoy:

Renaissance Women Painting Themselves, by Dr. Katherine A. McIver

Two of a Kind: Giovanna Garzoni and Artemisia Gentileschi, by Dr. Mary D. Garrard

Do We Have Any Great Women Artists Yet?, by Dr. Sheila ffolliott

The Politics of Exhibiting Female Old Masters, by Dr. Sheila Barker

A Clara Peeters for the Mauritshuis, by Dr. Quentin Buvelot

Floral Still Life, 1726—A Masterpiece by Rachel Ruysch, by Dr. Lawrence W. Nichols

The Protofeminist Insects of Giovanna Garzoni and Maria Sibylla Merian, by Prof. Emma Steinkraus