Guest post by Anastazja Buttitta, Curator, the U. Nahon Museum of Italian Jewish Art, Jerusalem

The life of Jewish women in Italy from the early modern period until World War II was uniquely complex. Though confined to traditional feminine roles in a patriarchal society, they managed to find a voice of their own and to establish an independent identity.

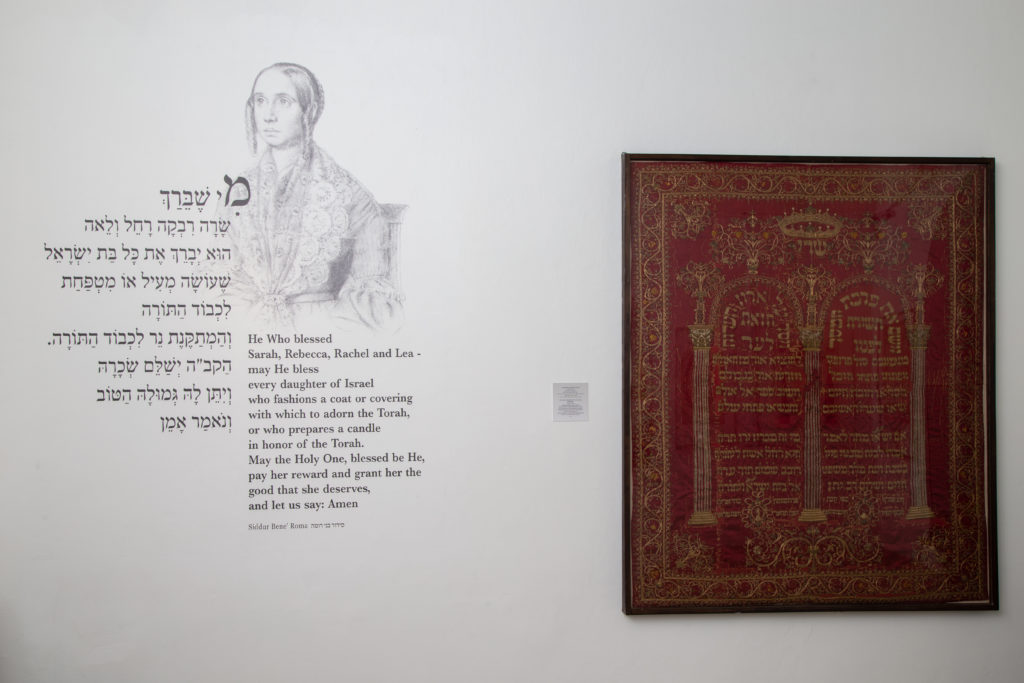

Italian-rite prayer books—among the most ancient Jewish religious writings—recognized women’s contributions with a special prayer recited during the Sabbath morning services, blessing “every daughter of Israel who makes a mantle or cover for the Torah.” (Image 1)

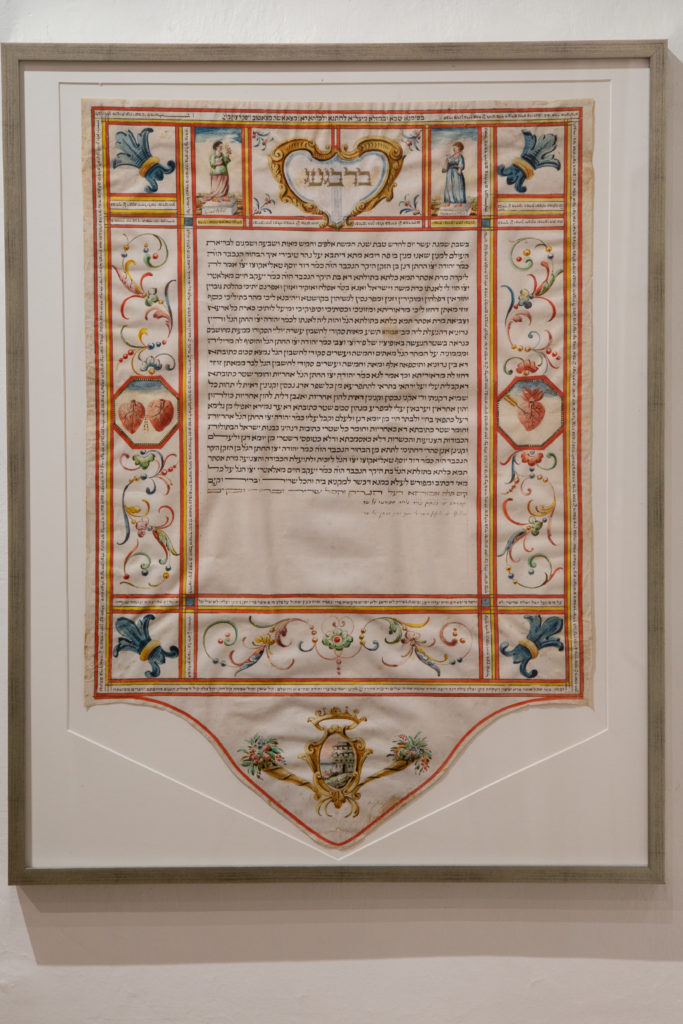

Jewish culture in the Diaspora was already firmly established in the Babylonian exile, when Queen Esther saved the Jews from annihilation. This event is celebrated annually during the Purim holiday, with the Book of Esther read in the synagogue. Similarly, one of the most ancient documents in Western civilization is the ketubbah—the Jewish marriage contract handed to the bride during the wedding ceremony, which protects the wife’s rights in the marriage. (Image 2)

However, Jewish social reality in the Italian peninsula was different than elsewhere in Europe. Since medieval times, the Italian Jewish community was a melting pot of Jewish populations arriving from Judea under Roman rule, and later from Sephardi and Ashkenazi communities in other countries.

In Renaissance Italy, influenced by humanist ideals, the status of women was significantly elevated, especially in the upper classes. We know of women who were poets, writers, physicians, and successful merchants. Italian Jewish women, the most elegantly and lavishly dressed in the Jewish world, were not only mothers and wives but also well-educated business managers. Many of them took part in their family’s business in the textile trade, contributing greatly to the arts of dressmaking, embroidery, the renewal of old fabrics, and bookmaking.

The traditional feminine role of the efficient housewife was enhanced by several religious concepts that are fundamental for Jewish art. One was the idea of הידור מצוות (hiddur mitzvoth), literally the “beautification of the precepts and commandments”.Another was the concept of לעלות בקודש (la’alot ba’kodesh), literally “elevation in holiness,” signifying the transformation of a mundane object into a ceremonial and sacred one. Both ideas were realized by creating beautiful, sumptuous, and colorful textile objects.

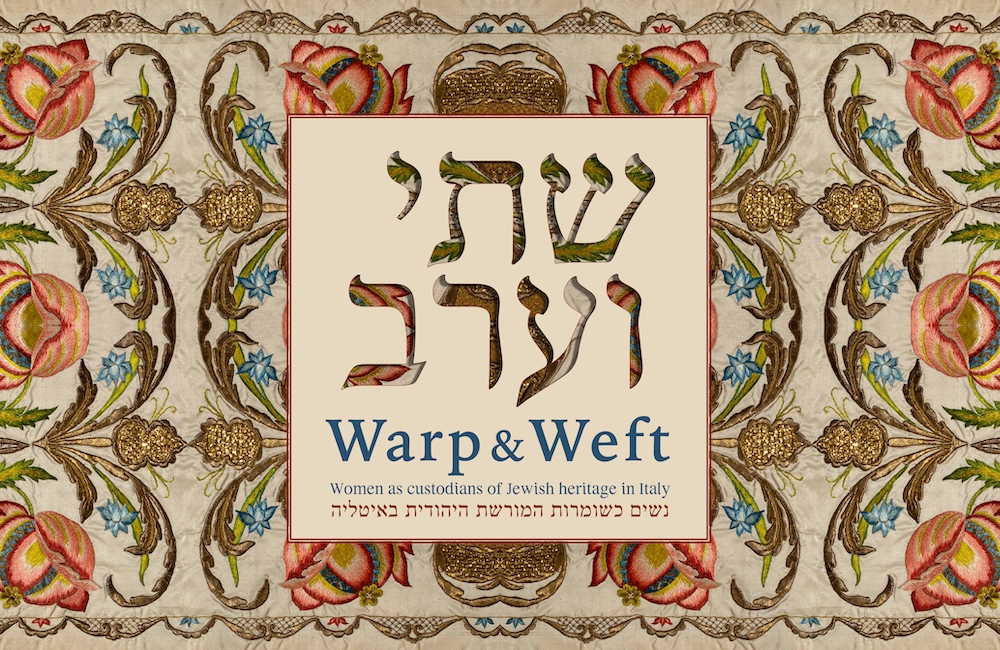

The exhibition Warp and Weft—Women as Custodians of Jewish Heritage in Italy, presented at the Umberto Nahon Museum of Italian Jewish Art in Jerusalem explored the role of the Italian Jewish woman in all its shades and textures, represented in the unique and precious textile collection of the Museum. The exhibition acquainted us with the names of a number of Italian Jewish women who sought to leave a lasting mark of their devotion, love, and labor, and whose voice found its best expression through fabrics and textiles.

Textiles and Ritual

The oldest Italian ceremonial synagogue textiles known to us are dated to the late sixteenth century, and all of them are signed by women. This attests to the active role women played in Jewish religious life and to their interest in contributing to the community. The Torah ark here presented (Image 3), was commissioned by a woman, Sara Consiglia Norsa, the well-educated wife of a rich banker living in Mantua in the mid-sixteenth century.

In Jewish tradition, the synagogue is perceived as a sanctuary and a symbolic substitute for the Temple of Jerusalem. Similarly, the Torah scroll is identified with the Tablets of the Law, and the Torah ark symbolizes the Ark of the Covenant.

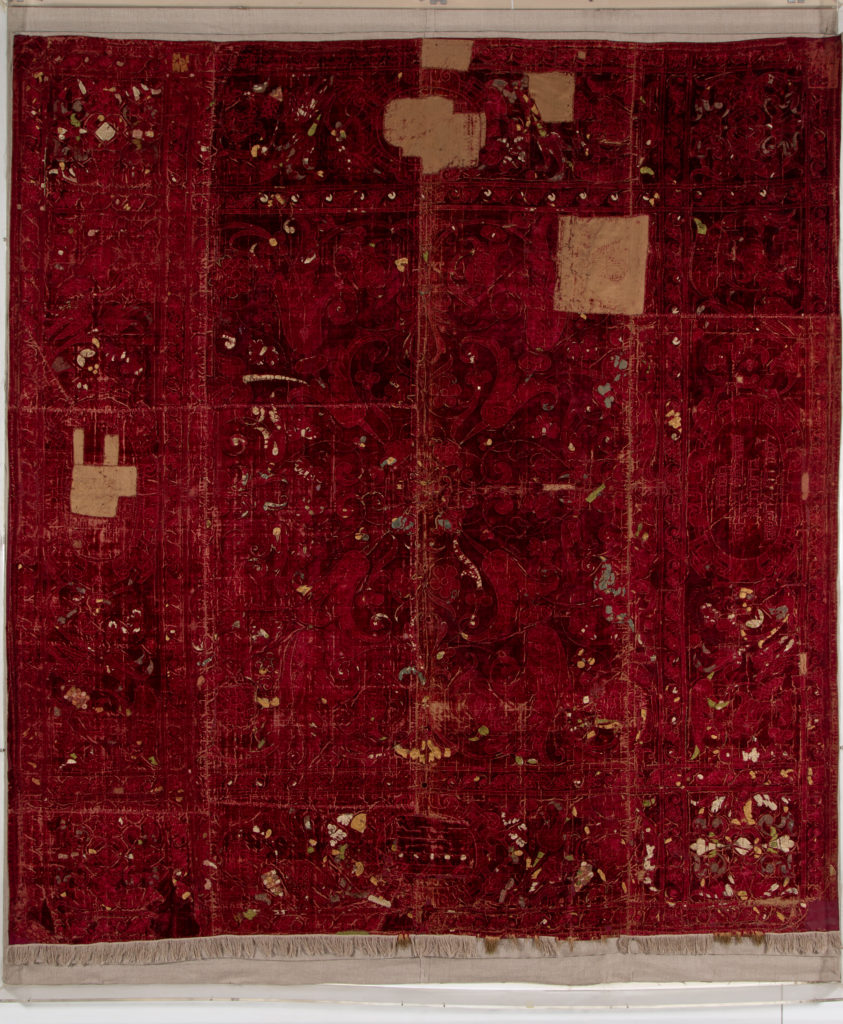

The Parokhet—the Torah Ark curtain—is a textile conveying the values represented by the ark and the Torah itself (Image 4).

The Meil—the mantle covering the Torah scroll – was often donated in order to protect the scroll, to give thanks to God, or to commemorate a departed loved one (Image 5).

Italian and Sephardi Jews also used a Mappah for wrapping the Torah scroll. The Mappah was made of simple fabrics such as cotton and linen, and its purpose was to protect the scroll from humidity (see image 3, above).

What strikes us in these textiles is the refined sense of fashion and decoration that women employed as a means of expressing their devotion.

Bride and Mother

The fundamental role of the Jewish Italian woman was, of course, in the household, as spouse and mother. Every important moment in a woman’s life cycle was enshrined in textiles, usually pieces embroidered by her. As future brides, women embroidered the tallit (prayer shawl) for their fiancé (Image 6).

On the wedding day they would usually wear a bridal veil passed down in the family from generation to generation. When a boy was born, women would sew an avnet, or fascia in Italian—the long, tight piece of cloth in which the baby was wrapped during the brit milah (circumcision ceremony), which would later be donated to the synagogue as a binder for the Torah scroll. This tradition is related to the manufacture of Torah binders—long pieces of textile created exclusively as ritual ceremonial objects. Interestingly, the embroidered and lace-work decoration of these textiles is rooted in the Italian Renaissance and Baroque styles. And, of course, women would sew and decorate children’s clothes (Images 7 and 8).

Sometimes these fabrics are inscribed with embroidered dedications, used to commemorate important events in the family’s life or to honor the memory of a family member, often the father or the husband.

Working Women

Beginning in the early modern period, Italy became the leading center for embroidery in Europe. Embroidery was a women’s art form and an important part of female education since the sixteenth century. Italian Jewish women figured prominently in the manufacture of embroidered textiles for use in the synagogue, as did their sisters in other countries.

This activity perfectly fit social expectations regarding women: they were to exhibit “feminine” traits such as patience, perseverance, precision, and tranquility. In addition, as in the case of Christian women, embroidery and lacework offered a way for women to increase the family income without leaving the home. (Image 9)

The principal Italian centers for textile production and decoration were Venice, Florence, and Livorno. Embroidery and lace were so integralI to contemporary styles and techniques that the women producing them could by no means be considered amateurs. Furthermore, these activities allowed women to consult pattern books for weaving, embroidery, and lacework circulating throughout Europe, affording them the opportunity to gain literacy skills and to acquaint themselves with international fashion trends.

Thus, for example, in the late nineteenth century two Italian Jewish women founded professional textile workshops for the neighborhood’s impoverished Christian housewives. They were the philanthropists Virginia Nathan from Antella, near Florence, and Alice Franchetti from Città di Castello, in Umbria.

The Art of Recycling

Italian Jews were denied membership in guilds. Judging by the amount of textile works that have survived, we may presume they were mainly active in the fabric industry and as textile merchants.

Jewish ceremonial objects were always made from the finest materials. However, precious and beautiful fabrics were often reused to make ceremonial synagogue textiles. This was facilitated by the traditionally Jewish trade in second-hand clothing. In general, the secondary usage of old fabrics was very common in Europe between the sixteenth and the eighteenth centuries.

According to Jewish tradition, the renewal of textiles for ceremonial purposes was seen as “elevating the holiness” of the mundane object—a process in which women played an important role. (Image 10)

It is interesting to draw some comparisons between aristocratic women’s dresses, mostly of French production, and synagogue ritual textiles in similar patterns, probably made a few decades later using “recycled” fabrics. There is also a clear connection between the form of the Meil—the Torah mantle—and garment design (Image 11).

Dr. Anastazja Buttitta is the Curator of the U. Nahon Museum of Italian Jewish Art in Jerusalem. Since completing a BA and a master’s degree with honors in the Department of Art History at the University of Florence, she has been specializing in Applied Arts and Jewish Italian Art. In 2018 she submitted, at the Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, her doctoral research on jewelry as an expression of social and cultural values in Venice in the early modern period (1400-1600). Her doctoral thesis explores the jewels in terms of iconography, techniques and historical context and to look for their sources of artistic influence, ties and relationships with other traditions.

More Art Herstory exhibition reviews and/or blog posts about women’s textile art:

The Theatrical Wonders of Jeanne Paquin’s Belle Époque Parisienne, by Julia Westerman

“Black-works, white-works, colours all”: Finding Susanna Perwich in her Seventeenth-Century Embroidered Cabinet, by Isabella Rosner

Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists, by Dr. Elizabeth Sutton

‘Bright Souls’: A London Exhibition Celebrating Mary Beale, Joan Carlile, and Anne Killigrew, by Dr. Laura Gowing

More Art Herstory blog posts about Italian women artists:

“La grandezza del universo” nell’arte di Giovanna Garzoni / “The grandeur of the universe” in the art of Giovanna Garzoni (Guest post/review by Dr. Sara Matthews-Grieco)

A Tale of Two Women Painters, Guest post / exhibition review by Natasha Moura

In defense of monographic exhibitions of female artists: The case of Fede Galizia, by Camille Nouhant

The Ladies of Art are in Milan, by Dr. Cecilia Gamberini

“Artemisia” at the National Gallery: A Review, by Dr. Sheila McTighe

Elisabetta Sirani of Bologna (1638–1665), Guest post by Dr. Adelina Modesti

Plautilla Bricci (1616–1705): A Talented Woman Architect in Baroque Rome (Guest post by Dr. Consuelo Lollobrigida)

Two of a Kind: Giovanna Garzoni and Artemisia Gentileschi (Guest post by Dr. Mary D. Garrard)

Sister Caterina Vigri (St. Catherine of Bologna) and “Drawing for Devotion,” Guest post by Dr. Kathleen G. Arthur

Orsola Maddalena Caccia (1596-1676), Convent Artist, Guest post by Dr. Angela Ghirardi

Rediscovering the Once Visible: Eighteenth-Century Florentine Artist Violante Ferroni, Guest post by Dr. Ann Golob

Renaissance Women Painting Themselves, Guest post by Dr. Katherine McIver

The Priceless Legacy of Artemisia Gentileschi: A Curator’s Perspective, Guest post by Dr. Judith W. Mann

Bravo Anastazja, a wonderful exhibition.

Thank you so much, A.!

this looks like a wonderful exhibition. I wonder if there is a catalogue for it? Please let me know.