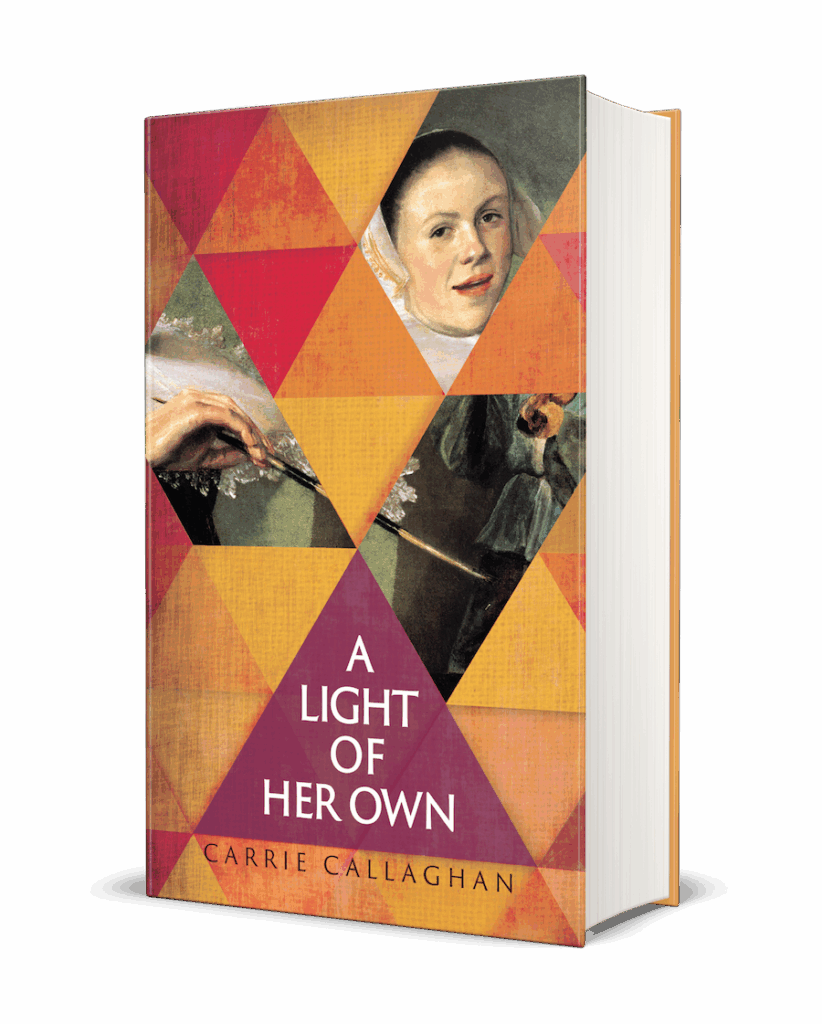

Q&A about Judith Leyster (1609–1660), the protagonist of Callaghan’s 2018 novel

We notice an exciting new trend in publishing: real women artists from the distant past feature as protagonists in new works of historical fiction, and as subjects of scholarly studies. This post is the second installment of an occasional feature on the Art Herstory blog: interviews with book authors, whether fiction or non-fiction, about female artists from past centuries.

Although A Light of Her Own is a work of fiction, its main character, Judith Leyster, was an actual painter during the Dutch Golden Age. Her works—many of which still exist today, and can be viewed in museums and/or online—include genre scenes, portraits, and at least one still life. She is documented as one of the first women ever to be admitted to the Saint Luke’s Guild of Haarlem.

Amberjack Publishing, 2018

Selected by the Washington Independent Review of Books

as one of 50 Favorite Books of 2018

The Publishers Weekly review (November 2018) offers this description and accolade of the novel: “Callaghan skillfully balances both the intricacies of the 17th-century Dutch art world and the religious persecution of the time, making this a dextrously woven and engrossing historical novel.”

Here, author Carrie Callaghan discusses aspects of working with this female Old Master as a character in her debut novel.

How did you come to write about Judith Leyster?

I live near downtown Washington, DC, and I love going to the National Gallery of Art for a dose of soul-restoration and joy. One day some years ago, I was wandering around the Dutch galleries there when I came upon an exhibit of paintings done by a woman. A woman painting at the time of Rembrandt—Judith Leyster. My jaw practically hit the floor, and I was enthralled. How had she managed to paint so much and so successfully? I use my writing as a way to explore my questions about today and the past, so I knew I had to write Judith’s story.

How did you go about researching Judith Leyster and her time period?

Naturally, I started with the paintings and the scholarly work done on the paintings. When I was eight months pregnant with my first child, I went to the Library of Congress and pulled all the books they had on her, including a collection of essays written by leading scholars to support an earlier exhibit of Judith’s paintings. After what I learned about Judith, and how she managed to continue painting even after she had children of her own to care for, that first research trip seems fitting. Of course, beyond that, I relied on books, more paintings, and interviews.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

What is your favorite painting by Judith Leyster, and why?

Judith has such wonderful, expressive paintings, and yet it’s easy for me to pick my favorite: her self-portrait, which hangs on the walls of the National Gallery of Art and graces the cover of my book. When I was writing the scene where Judith applies to the St Luke’s Guild, which she needs to join in order to work as a professional painter, I had to pick a painting for her to present as her “master piece.” The books noted that they didn’t know what she used, so I looked at her charming set pieces and genre paintings. None, however, had the bold spirit of her self-portrait, and that’s how I wrote the scene. Of course the bold Judith would choose her own face to present to this room full of men, sitting in judgment of her. Or so I imagined.

A year ago, I was chatting on the phone with the leading Judith Leyster scholar.

“You know,” she said. “We’ve recently identified which painting Judith presented for her Guild master work.”

I sucked in a breath. “Yes?”

“It was her self portrait.”

I had chills.

There’s a lot of description of painting technique in the novel. Are you a painter yourself?

No, though I miss the drawing I used to do in high school. My mother and grandmother are both painters, however, so I felt like I was honoring their legacy by writing about Judith. All three women struggled to balance motherhood, art, and livelihood, and I felt closer to my family after I tried to see the world through Judith’s eyes.

Since publication, has your book popped up in any exciting, artsy places?

I haven’t checked, but the book buyer at the National Gallery of Art said that A Light of Her Own is for sale there! That’s pretty much my dream spot. And I’ve been so thrilled to be embraced by the wonderful community of art-loving book readers. The enthusiasm has been a surprise, and so inspiring.

National Museum of Women in the Arts.

Have you had any interesting interactions with any of those art lovers?

Actually, yes. While the book was awaiting publication, I visited the National Museum of Women in the Arts with a friend. We walked up the stairs and the first painting I saw was, quite obviously, a Judith Leyster work. I ran over and stared. As I marveled, I noticed that another woman was equally enraptured.

“You must be a Judith Leyster fan,” I said.

“Oh yes,” she replied.

I mustered up all my courage, took a deep breath, and rushed out the words, “I wrote a book about her!” And then I blushed deep red.

“I wrote a story about her!” She grinned.

We both squealed, compared notes about our love for Judith Leyster, and then parted.

A few minutes later, she came up and tapped me on the shoulder.

“Carrie, I have to tell you,” she said. “I showed my friend the bookmark you gave me, and she had a confession. She had already pre-ordered your book for me.”

I blushed even deeper red, and told her I looked forward to seeing her writing on Judith published some day. And all the while, I felt like Judith was smiling down on us, this confederacy of her fans.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

Carrie Callaghan’s A Light of Her Own was issued in 2018 by Amberjack. Publishers Weekly called it “a riveting debut,” and it was one of the Washington Independent Review of Books “Favorite Books of 2018.” Her second novel, Salt the Snow, about the 20th century American journalist and firebrand Milly Bennett, comes out in 2020. Carrie lives in Maryland with her spouse, two children, and two ridiculous cats.

More blog posts by authors of historical fiction:

Talking Artemisia Gentileschi with Joy McCullough, Author of “Blood Water Paint”

The Abstract-Impressionism of Berthe Morisot and Joan Mitchell, a guest post by novelist Paula Butterfield

Victorine Meurent, More than a Model, by Drēma Drudge

More Art Herstory blog posts to do with Dutch/Flemish women artists:

Floral Still Life, 1726—A Masterpiece by Rachel Ruysch, by Dr. Lawrence W. Nichols

Women Artists of the Dutch Golden Age at the National Museum of Women in the Arts

Gesina ter Borch: Artist, not Amateur, by Dr. Nicole E. Cook

The Protofeminist Insects of Giovanna Garzoni and Maria Sibylla Merian, by Prof. Emma Steinkraus

Susanna Horenbout, Courtier and Artist, by Dr. Kathleen E. Kennedy

More Art Herstory blog posts:

Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists (guest post by Dr. Elizabeth Sutton)

The Priceless Legacy of Artemisia Gentileschi: A Curator’s Perspective (Guest post by Dr. Judith W. Mann)

‘Bright Souls’: A London Exhibition Celebrating Mary Beale, Joan Carlile, and Anne Killigrew (Guest post by Dr. Laura Gowing)

New Adventures in Teaching Art Herstory (Guest post by Dr. Julia Dabbs)

Renaissance Women Painting Themselves (Guest Post by Dr. Katherine A. McIver)

A Dozen Great Women Artists, Renaissance and Baroque

Why Do Old Mistresses Matter Today? (Guest Post by Dr. Merry Wiesner-Hanks)