Guest post by Cathy Hall-van den Elsen, Independent scholar

Researching the life and work of the Spanish sculptor Luisa Roldán has been a lifelong endeavor. In 2020, as Covid set in and I waited for the publication of my book Luisa Roldán, I wondered about other early modern women artists in Iberia. Who were they? What were their lives like? How did they find their places in Spanish and Portuguese societies, as women and as artists? How did their experiences differ from those of their male peers? Before I could seek the answers to those questions my first task was to find them!

Visibility

One rarely finds contemporary accounts of early modern women artists in compendia of “famous artists.” Even when authors included them, they tended first to define them by their social connections and feminine attributes. Just a little attention was paid to their artistic production, which was mostly treated as a curiosity. In Spain and Portugal the biographers Palomino (Vidas, 1715–24) and Froes Perym (Theatro heroino, 1736) replicated the established, accepted approach. The critical perspectives that today’s readers might expect were far from their thoughts and from those of their peers.

Woman + Artist

With the unusual status of “woman + artist,” many of the artists I found shouldered responsibility for their domestic environments. Besides the procreation and care of children, or the support of their convent homes, some managed to navigate the challenges that lay in their paths. For others, career longevity proved to be elusive, and for a range of reasons they were unable to develop their early promise.

In Plain Sight

A small number of women artists in Iberia, including Sofonisba Anguissola, Josefa de Ayala (also known as Josefa de Óbidos) and Luisa Roldán were easily found. Palomino mentioned their names and they remain moderately well known.

Out Of Sight

Palomino identified other accomplished women artists in Iberia, including Mariana de la Cueva, whose star shone in Granada for a brief moment, but quickly faded (Fig. 4). The noblewomen Duquesa de Aveiro and the Duquesa de Villaumbrosa apparently left paintings that have now disappeared. Dorothea and Margarita Joanes, the daughters of the Valencian painter Joan de Joanes, were remarkably talented, but I have found no work that could reasonably be attributed to them.

In the Shadows / Invisible

We know of some women (for example Maria Josefa Sánchez, Fig. 5) through their signatures on art works. However, at present we have almost no details of their lives.

Wives and Daughters

Work by daughters and wives was often unsigned and incorporated into their male relatives’ output. While their work may still exist—perhaps even returning our gaze in churches or museums—we don’t recognize it. We know of just three sculptures by Luisa Roldán‘s sister María Roldán, dated when María was already a mature woman (Fig. 6). But the Virgin of the Snow and the two sculptures that accompanied it are unlikely to have been her only work.

Asserting Identity

By asserting their identity in various ways, these women let us know that they, and their work, were worthy of attention. Their signals reinforce the now-obvious fact that women artists were present, active, and valued in the early modern Iberian environments they inhabited.

The Mirroring Gaze

Sofonisba Anguissola’s self-portrait (Fig. 2) and Josefa de Ayala´s Saint Catherine (Fig. 3) directly look out of their space, fixing the viewer with self-aware, mirroring gazes.

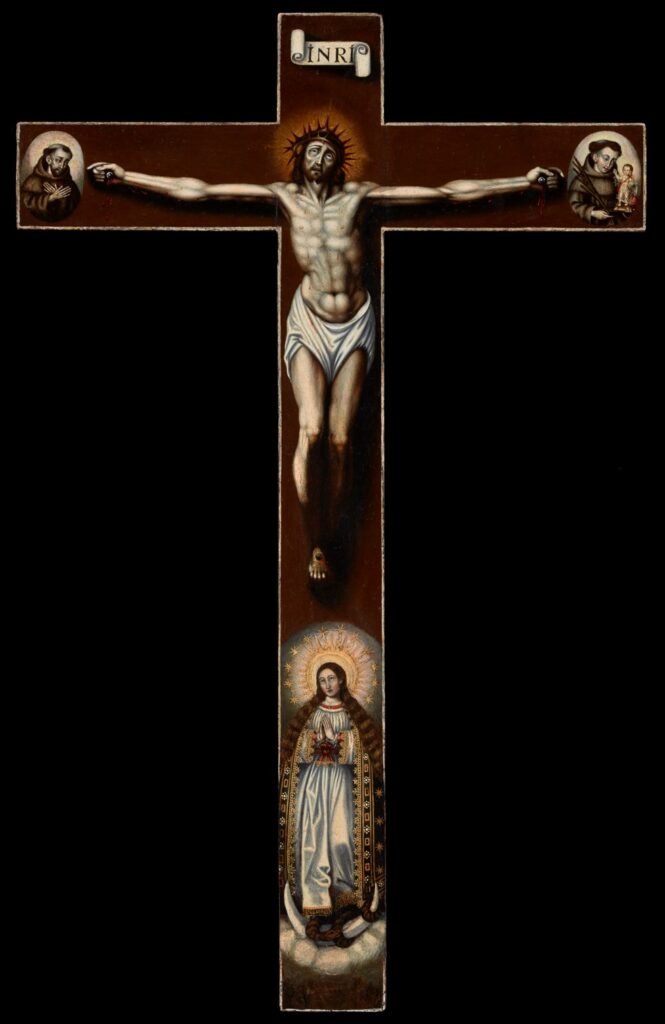

Claiming Space

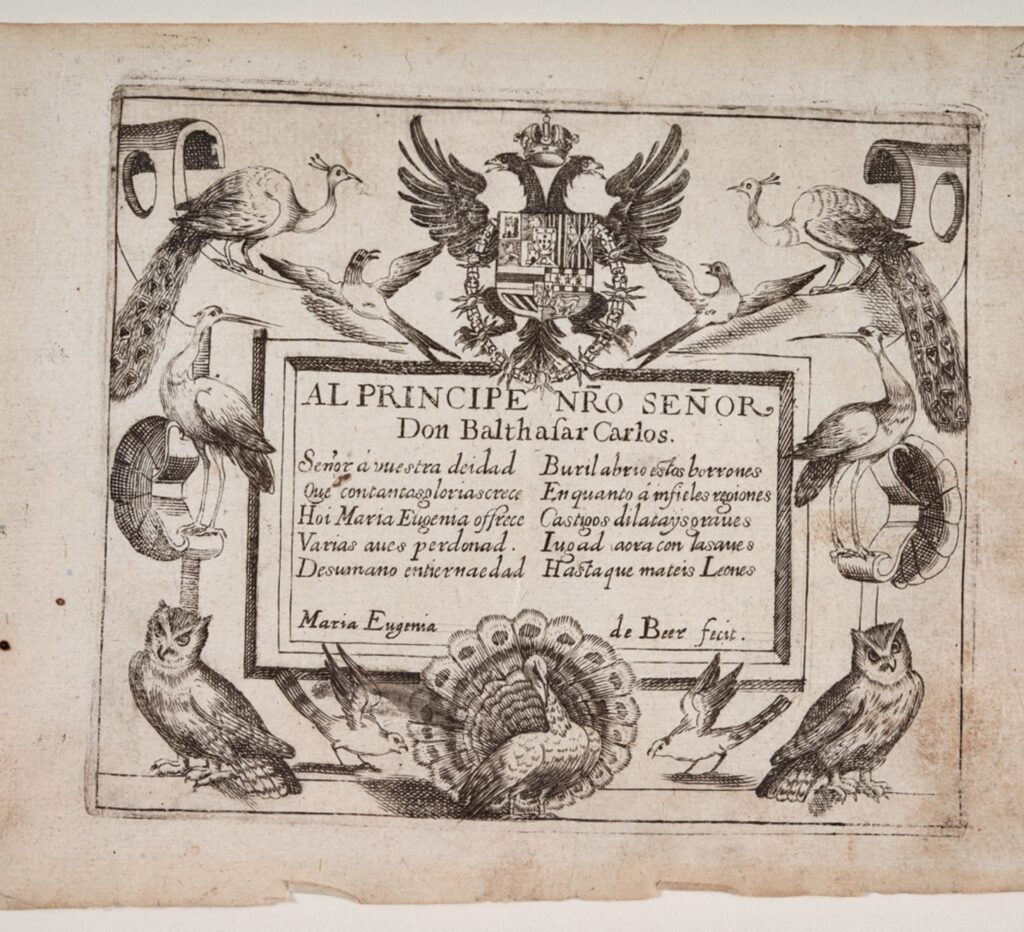

María Eugenia de Beer fondly addresses Crown Prince Balthasar Carlos on the front page of her book of engravings (Fig. 8). María Eugenia, Luisa Rafaela de Valdés and María Josefa Sánchez claim an elevated social status by including the honorific “Doña” in their signatures (Figs. 5, 7, and 9). Soror Joana Baptista (Fig. 10), and Sor Andrea de la Encarnacion (Fig. 11) left clearly visible signatures on their work. Luisa Roldán included her title, “Escultora de Cámara” on the work for which she is best known (Fig. 1).

Historiography and Environment

Few of the women I studied have ever been the subject of significant historiographical attention. Despite their absence from popular history, the artistic work that they left proclaims, even celebrates, their identities. Gendered roles for women in early modern Iberia carried responsibilities that, in favorable circumstances, and when carefully managed, could allow for continuing artistic practice. Despite their negligible presence in the historiography of past centuries, I found women who were confident in their practice, and unafraid to claim recognition of their talent. None set out to challenge the status quo or to disrupt their communities. Each one achieved what they could with their talent and their creative drive, while maintaining their socially constructed identities.

Stirring Women into History?

Joan Wallach Scott (in Gender and the Politics of History) and Merry Wiesner-Hanks (in Gender in History) both opined that we should do more than just “stir women into history.” We should also examine the circumstances surrounding their creative practice. These artists left silent pleas in their gaze and in their signatures. We can respond to their pleas by recognizing them, acknowledging their achievements, examining the factors that influenced their creative production, and exploring how gender and social status affected their practice and the reception of their work.

Dr. Cathy Hall-van den Elsen studied Spanish art at La Trobe University in Melbourne, Australia, completing her Ph.D (1992) on the life and work of Luisa Roldán. After a period working outside art history Cathy returned to scholarship in 2005, contributing the introductory chapter to the 2007 exhibition catalogue Roldana. She is the author of the Spanish-language monograph Fuerza e Intimismo: Luisa Roldán, escultora (1652–1706). Oxford Bibliographies Online published her annotated bibliography on Luisa Roldán. Her book Luisa Roldán appeared in 2021 as the inaugural volume in the book series Illuminating Women Artists (it was shortlisted for Apollo Magazine Book of the Year, 2021 and Honorable Mention, GEMELA Book Awards 2022). Cathy’s study Gender and the Woman Artist in Early Modern Iberia won the 2024 GEMELA Best Book Award. A second edition of her Spanish monograph entitled Luisa Roldán, escultora: Fuerza e Intimismo is forthcoming in 2024. Follow Cathy on Academia.edu.

More Art Herstory guest blog posts you might enjoy:

Finding Luisa Roldán: A North American road trip, by Cathy Hall-van den Elsen

Sofonisba Anguissola: Portraitist of the Renaissance at Rijksmuseum Twenthe, by Nelleke de Vries

Why Do Old Mistresses Matter Today?, by Merry Wiesner-Hanks

New Adventures in Teaching Art Herstory, by Julia Dabbs

Renaissance Women Painting Themselves, by Katherine A. McIver

A Tale of Two Women Painters, by Natasha Moura

The Politics of Exhibiting Female Old Masters, by Sheila Barker

Do We Have Any Great Women Artists Yet?, by Sheila ffolliott