Guest post by Cathy Hall-van den Elsen

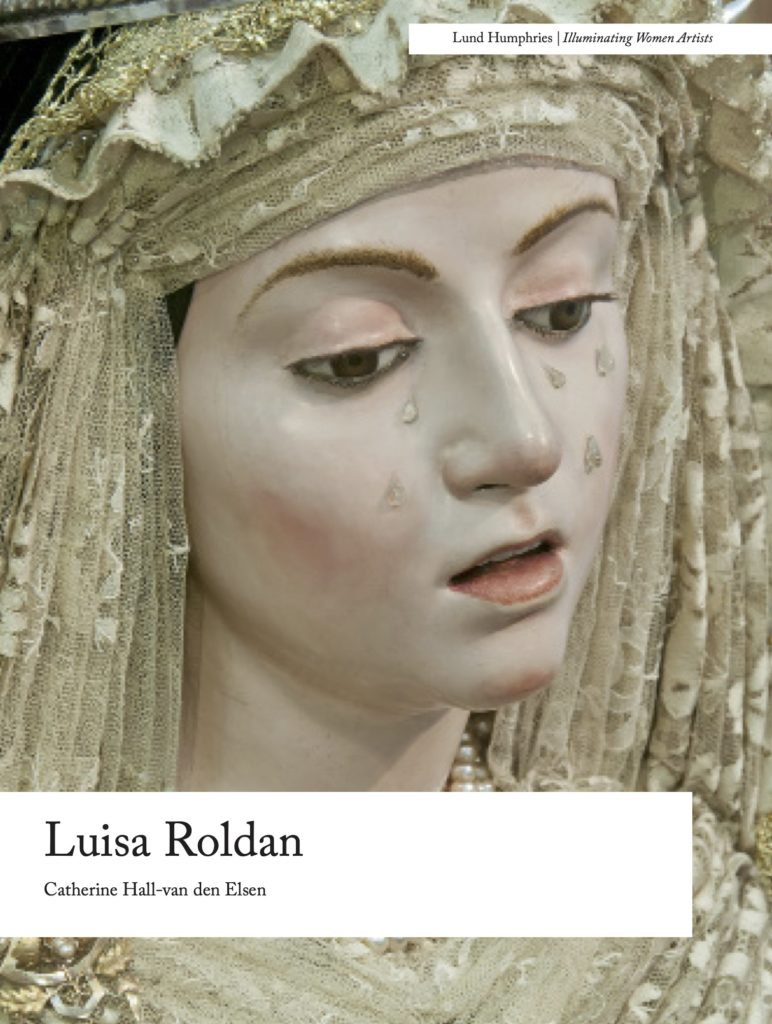

The Spanish sculptor Luisa Roldán (1652–1706) was recognised in her lifetime as an artist of considerable talent. Luisa was born in Seville, the daughter of Pedro Roldán, a prominent sculptor.

Early in her career she carved life-sized wooden figures of Christ and (predominantly male) saints. These statues were painted, and sometimes gilded, to produce strikingly realistic images for altarpieces and processional floats. Many of these can still be seen in the Andalucían convents, chapels and churches for which she made them.

As she matured, Luisa expanded her repertoire to include work in terracotta, from which she created small groups depicting the Holy Family and the saints. After moving to Madrid, she spent seventeen years producing work in wood and terracotta for two Spanish kings and for members of the aristocracy. By the time she died in 1706, she was acknowledged as one of Spain’s finest sculptors. In subsequent centuries her memory lingered as one of Seville’s favorite daughters, but her name was rarely mentioned in the art historical literature.

The easy exchange of photographs and opinions facilitated by the internet has enabled comparisons between signed and unsigned pieces, which has contributed to a re-awakening of appreciation of Luisa’s talent and an enhanced understanding of her style. An exhibition in Seville in 2007 brought together examples of her work to the public gaze for the first time. Scholars began to pay more attention to the artist, and there was an increase in the number of sculptures persuasively attributed to her.

After my first encounter with one of Luisa’s terracotta sculptures more than thirty years ago, I began the process of reconstructing her life and her artistic production. I have followed her trail through archives, museums, churches, convents, and private houses across Europe, the United Kingdom and North America. My visits from Australia to one or another continent usually involved zig-zagging across borders and time zones, for the opportunity to meet curators and to study each sculpture, absorbing what I could for the short time that I had.

My most recent trip to a few North American cities allowed me to re-acquaint myself with work I knew well, and to see some recently acquired Roldán sculptures. As covid-19 began its global assault I flew home, reflecting that the fourteen examples of Luisa’s work in eight North American cities represent a unique snapshot of her production in wood and terracotta. This sampling encompasses her early period through to her late works, incorporating the expected and the unexpected, the striking, the tender and the unsettling. My North American road trip from west to east, visiting museums both large and small, illuminates the breadth of Luisa Roldán’s creativity.

Los Angeles

Los Angeles hosts two works in wood, a material that Roldán mastered in her father’s workshop.

LACMA, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, has a little-known group in wood of 75cm in height, depicting Saint Anne and the Virgin Mary reading, which probably dates from the 1680s, her Cádiz period. This work reflects one side of the contemporary debate about girl’s education, which was discouraged by some writers and supported by others. Luisa depicted the subject in terracotta at least three times during the following decade, including one that is now in the Blanton Museum of Art in Austin, Texas.

The San Ginés de la Jara in the J. Paul Getty Museum is a masterful, almost life-sized work that demonstrates Luisa’s ability to convey the aging saint’s restrained emotion. Made during her time in Madrid, San Ginés’s facial features repeat those of the older men she sculpted in Cádiz. His robe’s estofado, created by layering gilt and paint is among finest known examples in all her output, probably painted by Luisa’s brother in law Tomás de los Arcos.

Mexico City

Mexico City’s Museo Nacional de Historia produced a catalogue in 1975 that included a black and white photograph of a Virgo Lactans by Luisa. Although I have not had the opportunity to study the original work, the image repeats the simple structure that she produced a number of times throughout her career, reflecting the tender relationship between the mother and the child on her lap.

Austin

The Blanton Museum of Art in the University of Texas at Austin has one of three known examples in terracotta of the Education of the Virgin that date from Luisa’s time at the Spanish court. Beautifully restored in 2018, the group reveals the sculptor’s delicate handling of clay to reproduce her characteristic facial features of youth and aging in male and female protagonists, as well as gentle folds of very fine drapery.

Dallas

Meadows Museum in Dallas, Texas holds a small Saint John the Baptist, a precious portrait of a healthy young boy. His rounded features, animal skin robe and unruly locks establish a model for other terracotta versions of the young saint that have been identified as Luisa’s work in Mostoles, Madrid, Spain’s National Sculpture Museum in Valladolid and the Loyola University Museum of Art (LUMA) in Chicago (see below).

Chicago

A similar figure can be found in the intimate group of the Virgin and Child with the Young Saint John in the Loyola University Museum of Art (LUMA). Rocks on the side of this group bear the date of execution 1692 and the names of both Luisa and the painter, her brother-in-law Tomás de los Arcos. The names and date are most useful in enabling scholars to establish this as an early piece from her Madrid period.

Detroit

While she is best known for her production of multi-figured, brightly coloured groups, the Detroit Institute of Art acquired in 2018 an important, unusual Roldán relief in terracotta of the Virgin of Atocha.

One of only four known relief sculptures by Luisa, this study of stillness in black, grey and silver reminds us of her versatility. Signed and dated 1705, it is likely to have been among the last works she completed before her death in January 1706.

Toronto

The Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto has a small Saint Michael and the Devil, Luisa’s earliest known work held in a North American collection.

This Saint Michael, made of polychromed wood probably in the 1670s, reflects her early training in her father’s workshop before she embraced a more dynamic style like that seen in the life-sized sculpture of the same saint in the monastery of El Escorial, Madrid. The figure’s features, hair and the gentle movement implied in the saint’s skirts are strongly reminiscent of the angels she sculpted for Andalucían brotherhoods and churches in the period 1678–1687.

New York City

Among Luisa’s work in New York is the Metropolitan Museum’s late piece in terracotta, depicting the Entombment of Christ. Probably presented to King Felipe V in 1701, this work reminds us of her father’s altarpiece of the same subject that she would have known—and may have worked on—in Seville thirty years prior.

Like the Virgin of Atocha, the solemn subject matter reminds us that rather than restricting herself to decorative depictions of maternal love and happy childhood, Roldán embraced the later, darker moments of Christ’s life on earth, as befitting an artist of the Spanish Counter-Reformation.

The most beautiful and the most confronting of Roldán’s sculptures in North America can be found in the collection of the Hispanic Society of America (HSA). The incredibly accomplished representation of flesh, fabric, jewelry and natural materials, as well as the implied interactions between the protagonists in the Mystical Marriage of Saint Catherine suggests that Luisa must have produced this work for her royal patrons.

A similar quality is apparent in the figures Rest on the Flight into Egypt, in which the kneeling Saint Joseph presents a fig to the Christ Child, who sits on his mother’s lap under the protection of a pomegranate tree.

Contrasting these two scenes of beauty is the third group in the HSA collection, representing the Ecstasy of Mary Magdalene. Two angels attend the roughly clothed, penitent saint who lies on a bed of rocks. The iconography of the secondary details placed around the figure reinforce the importance of repentance and the rewards that await her in heaven.

The last two sculptures in this North American tour, the HSA’s severed heads of Saint Paul and Saint John the Baptist, challenge the popular image of Luisa as an artist whose best work is confined to the depiction of bouncing babies and rosy-cheeked mothers. The theme of the severed heads responds to a Spanish Counter-Reformation tradition that celebrated the martyrdom of saints as a reflection of their religious conviction. In these two challenging sculptures, Roldán reflected the acceptance of suffering and death as a vehicle for the affirmation of faith.

Conclusion

A North American road trip (perhaps better described here as an aeronautical expedition) would not normally be associated with the study of a Spanish female artist of the early modern period. In the case of Luisa Roldán, a tour of discovery across the continent yields a wealth of opportunities to appreciate the artistry with which she expressed the themes, the joys, and the challenges of Catholic Spain in the latter half of the seventeenth century.

Dr. Cathy Hall-van den Elsen studied Spanish art at La Trobe University in Melbourne, Australia. She completed her Ph.D (1992) on the life and work of Luisa Roldán. After a career outside art history Cathy returned to Roldán scholarship in 2005, contributing the introductory chapter to the exhibition catalogue Roldana, published by the Consejeria de Cultura in Seville in 2007. In 2018 Cathy published a monograph in Spanish: Fuerza e Intimismo: Luisa Roldán, escultora (1652-1706), (Madrid, CSIC). Her annotated bibliography “Luisa Roldán,” encompassing articles about the sculptor published in Spanish and English, has just been published in Oxford Bibliographies in Art History (ed. Thomas DaCosta Kauffman, New York: Oxford University Press, August 2020).

Cathy is the author of Luisa Roldán, the inaugural volume in the Lund Humphries English-language series Illuminating Women Artists. This book was published in September 2021; in November 2021, it was shortlisted for Apollo Magazine’s 2021 Book of the Year Award.

The book is available outside North America from Lund Humphries, and within North America from Getty Publications.

If you liked this Art Herstory guest blog post, you might also enjoy:

Luisa Roldán: Escultora Real Review, by Olivia Turner

Portrayals of Mary Magdalene by Early Modern Women Artists, by Diane Apostolos-Cappadona

Two of a Kind: Giovanna Garzoni and Artemisia Gentileschi (Guest post by Dr. Mary D. Garrard)

Lavinia Fontana: Italy’s First Female Professional Artist (Guest post by Dr. Elizabeth Lev)

“La grandezza del universo” nell’arte di Giovanna Garzoni / “The grandeur of the universe” in the art of Giovanna Garzoni (Guest post/review by Dr. Sara Matthews-Grieco)

Plautilla Bricci (1616–1705): A Talented Woman Architect in Baroque Rome (Guest post by Dr. Consuelo Lollobrigida)

Levina Teerlinc, Illuminator at the Tudor Court (Guest post by Louisa Woodville)

Susanna Horenbout, Courtier and Artist (Guest post by Dr. Kathleen E. Kennedy)

The Politics of Exhibiting Female Old Masters (Guest post by Dr. Sheila Barker)

Why Do Old Mistresses Matter Today? (Guest post by Dr. Merry Wiesner-Hanks)

Renaissance Women Painting Themselves (Guest post by Dr. Katherine A. McIver)

A Tale of Two Women Painters (Guest post by Natasha Moura)

The Priceless Legacy of Artemisia Gentileschi: A Curator’s Perspective (Guest post by Dr. Judith W. Mann)

Trackbacks/Pingbacks