A guest post by art historian Louisa Woodville

The Flemish-born miniaturist Levina Teerlinc (1510–1576) was a highly-paid member of the Tudor court. Monarchs Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary Tudor, and Elizabeth I commissioned works, including miniatures, from her. She was also Gentlewoman of the Privy Chamber.

We know this from sixteenth-century documentary records—warrants, Exchequer Accounts of the Treasurer of the Chamber, New Years Rolls, and Plea Rolls of the King’s Bench. (Plea rolls, uniquely British, record details of legal suits.)

Teerlinc’s father, Simon Bening of Bruges in Flanders, was a renowned illuminator. Did he teach his daughter the art of limning—painting in watercolor on fine calf skin, or vellum? Some historians have suggested that before her marriage, Teerlinc apprenticed with the Croatian artist Giulio Clovio for two years, when he lived in Rome. Sources indicate Teerlinc left for London around 1545 with her husband George. Upon their arrival, she was appointed as “paintrix, to have a fee of 40l. a year from the Annunciation of Our Lady last past during your Majesty’s pleasure.”

Teerlinc’s oeuvre

Art historians disagree about what Teerlinc painted. Some suggest that as a gentlewoman to the court, her painting duties were minimal. This suggestion, however, prompts the question: then why was she paid 40l per annum?

Five historians do agree that she limned a small illumination of Queen Mary Tudor, Mary with Figures in a Landscape,Michaelmas (autumn), 1553 (Fig. 1).

This illumination is located at the top of a plea roll, a scroll of parchment that records details of legal suits or actions in the Court of Kings Bench, the highest court of common law at the time. (Pleas were to be delivered in the “presence” of the monarch, who rarely attended. Artists compensated for this absence by decorating the initial letter “P” with a small drawing of the monarch, usually enthroned.)

Teerlinc painted this illumination after Mary, the daughter of Henry VIII and Katherine of Aragon, had raised an army against the young Lady Jane Grey, queen for nine days. Grey had been crowned after Edward VI, pressured by his Protector the Duke of Northumberland, willed his crown to his Protestant teenage cousin.

The image makes clear, in no uncertain terms, who is queen. The monarch is secure in her throne. Two attending angels practically hold her down. Behind her a cloth of estate bears the royal arms, encircled by a green wreath. A dove hovers. The vertical column of dove, royal arms and a crowned Mary, sword in hand, visually triggers reassurance of the Trinity.

On the left middle ground, further back, two angels escort Mary by her elbows as she gazes heavenward. She looks up at a ribboned scroll empty of words. On the top right of the illumination is an army set against a landscape of receding blue hills. Closer, under a blank white rectangle, four horsemen, some raising their arms, beckon to the cavalry. These are soldiers, no doubt, who valiantly fought in the skirmish between the Protestant forces of the Duke of Northumberland and those of Mary Tudor.

Visual echoes of Simon Bening’s illuminations are found in this plea roll. Specifically, a book of hours that Levina herself could have worked on—the Hennessy Hours, executed around 1530—shares some imagery. The white horse to Mary’s right, just above abandoned weapons, is strikingly similar to one in the Hennessy St. John on Patmos (Fig. 2).

Artists in both illuminations depict a grey horse sitting slightly back on its haunches. Paint is applied in loose strokes with soft cross-hatching defining shadows and contours.

A portrait type is established

Six historians ascribe another image to Teerlinc, Indenture between the Queen and the Dean and Canons of St. George’s Chapel (Fig. 3a and Fig. 3b), dated 30 August 1559. An illumination is included in this legal agreement between Elizabeth and the dean and canons of St. George in Windsor. It made sure that “thirteen poor men, decayed in Wars, and such like the service of the Realm”—in other words, thirteen soldiers—could enjoy a financially secure retirement at Windsor (fig 3a).

In this detail of this indenture (fig 3b), 26-year-old Elizabeth is enthroned in the ornamental splendor of a capital “E” enclosed in a rectangle. Tudor symbols abound: the Tudor crown—the same her father Henry VIII wore—sits atop her golden hair, loose around her shoulders. Strokes made by a thin-pointed brush define the strands. A fleur-de-lis on top of her scepter is echoed by one in a blue triangle, to the left of her person. It refers to the English claim of French soil.

A round-faced Elizabeth is wrapped in royal ermine. Curly gold lines dance on the page, enlivening the seated figure of the queen. Transparent paint is loosely applied; the brushstrokes around the drapery that folds around Elizabeth’s knees is particularly agitated. Wavy black lines likewise define Elizabeth’s close-fitting ruff lifting her neck and resting on her wrists. A ground of Lapis lazuli enlivened by arabesque lines of gold embellish the Cloth of Estate behind her. The same expensive pigment is echoed in cushions underneath her arms.

Elizabeth holds, as did Mary, the golden orb and scepter that reinforce her God-appointed right to rule (Fig. 4).

The orb symbolizes Godly power; the cross above a globe, Christ’s dominion over the world; and the monarch as God’s-appointed representative on earth.

The rendition of fingers and hands in the Teerlinc attribution is far from realistic, suggesting that perhaps this artist—Teerlinc or whoever—was simply not as proficient as Simon Bening.

Whatever its limitations, this portrait type became the trope by which a monarch was represented in patents, plea rolls, and other official documents. It harked back to earlier representations of kings found in English indentures and statutes, and it also looked to the future.

Teerlinc and Hilliard

A Black and White Miniature of Queen Elizabeth (Fig. 5), dated 1576 (when the queen was 43), is currently attributed to Nicholas Hilliard (1547–1619), who began limning for the queen in 1572. Eighteenth-century over-painting in this work, however, makes it difficult to ascertain the original strokes without infrared reflectography or x-radiographic analyses.

Both Roy Strong and Jim Murrell, experts in the field of sixteenth-century miniatures, suggest that Teerlinc taught Hilliard the art of limning. Could these two artists have collaborated on a work such as this? We don’t know whether Teerlinc ever met Hilliard, let alone worked with him. Experts, however, date Hilliard’s first miniature of Elizabeth to 1572—and Teerlinc was at the queen’s court until 1576.

The Ghent-Bruges school in which Teerlinc trained was inherently collaborative. One spectacular Flemish codex, the Grimani Breviary (1490–1520, Cod. Lat. I, 99 2138 Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, Venice) had the leading artists of the day illuminating its pages, including Teerlinc’s father, grandfather and uncle (Simon Bening, Alexander Bening, and Gerard Horenbout respectively). This collaborative tradition is the one from which Teerlinc emerged.

Hilliard himself was trained as a goldsmith, apprenticed to Robert Brandon, one of Queen Elizabeth’s two royal goldsmiths. Hilliard’s works of the 1570s pose particular challenges, as this was when he transitioned from jeweler to limner. Experts say he painted his first miniature of Elizabeth in 1572. Curators, in an effort to keep up with recent technological discoveries, attribute, de-attribute, and re-attribute works between the court’s new upstart, Hilliard, and the aging gentlewoman, Teerlinc.

In this particular miniature the queen, her gaze direct and countenance calm, is spectacularly dressed in her black and white colors. She wears a St. George and the Dragon pendant. The lapis lazuli background sets off her pale heart-shaped face, held up by an Elizabethan collar. Delicate white netting rests against her pale shoulders, with a black velvet ribbon creating a lively contrast. Black spikes of silk protrude from her bodice and sleeves.

The artist here has used linear strokes to define forms—Elizabeth’s eyes and eyelids are drawn with conscientiously-placed strokes, not forms created by nuanced shadowing. In a manner characteristic of Bening, individual strokes define Elizabeth’s wiry red hair.

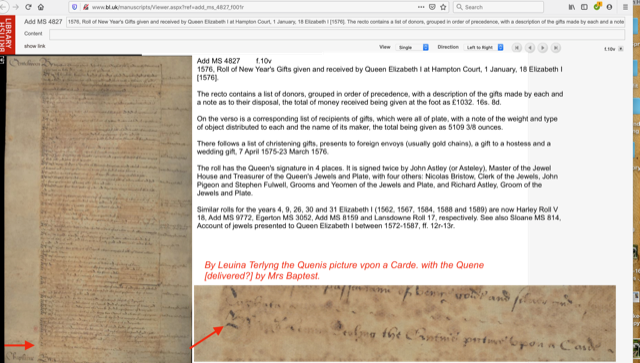

We do know Teerlinc’s final New Year’s gift to Elizabeth, as it is recorded in New Years Rolls at the British Library: “the Quenes picture upon a Carde” (Fig. 6, B.L., Addit. Ms 4827).

By Leuina Terlyng the Quenis picture vpon a Carde.

with the Quene by Mrs Baptest. 76.168

To Lauina Terling thre guilt Spones Brandon poz – vj oz di di qtr.

It is tempting to match extant miniatures to the ten gifts, cited in New Year’s rolls, that Teerlinc limned. In the absence of a specifically signed work or any documents proving authorship, however, it is impossible to match a given miniature to a specific record.

Teerlinc’s oeuvre revisited

So how can we confidently attribute any painting, let alone these, to Teerlinc?

Until we find more documentary sources that leave no doubt, we cannot. What we can do, however, is examine the now-available magnified details of illuminations and miniatures of works associated with her—her father Simon Bening, her uncle Gerard Horenbout and his children, her Antwerp cousins Lucas and Susanna Horenbout, and the renowned Hans Holbein who spent a dozen years in the court of Henry VIII. What colors did these artists use? How were these colors manufactured? Did a given artist use bold, confident strokes, or hesitant, weak ones? Who were the patrons, what subjects were depicted, and what fashions showcased? If they wrote treatises, what did they say? Who influenced them, and whom did they inspire?

When we stick to the facts, we do know that:

• Teerlinc came from a family steeped in the illuminating tradition. Her father, Simon Bening, was the foremost illuminator of sixteenth-century Flanders. He probably taught his daughter the art of limning. Teerlinc’s grandfather, Alexander Bening, also illuminated for monarchs and church elites. His patrons included Eleanor of Portugal and members of the Burgundian ducal household.

• Teerlinc was paid a hefty 40l from the royal accounts from 1545 until her death in 1576 (except during Mary’s reign, though she was later reimbursed 150l, under Elizabeth, for this unpaid annuity).

• Teerlinc’s contemporaries were impressed by her work. The sixteenth-century Florentine historian Lodovico Guicciardini heralds Teerlinc as the best of the women painters practicing at the time. Seventy-five years later, Flemish historian Antonius Sanderus assured his readers that she was “very capable in the two specialties of art.”

• Teerlinc is recorded as both an artist and a gentlewoman of the Privy Chamber, having been recruited to the court of Henry VIII by his last wife, Katherine Parr (perhaps at the instigation of her sister Anne Herbert). Teerlinc’s status was far more than that of an artisan.

• Teerlinc limned works that she gave to queens Mary and Elizabeth are recorded in the New Years Rolls of 1559, 1562, 1563, 1564, 1565, 1567, 1568, 1571, 1575 and 1576. We read that Teerlinc gave Elizabeth, for example, “the Quenis personne and other personages in a boxe fynely paynted. with her said majestie” (1562); “a Carde wheron is painted the Quene with many other personages” (1571); “a paper paynted with Quenis Matie and the knightes of thorder. Delyuerid to the said Blaunch Pary” (1568); and, the year of Teerlinc’s death, “the Quenis picture vpon a Carde” (1576).

Some historians suspect that Teerlinc has been overlooked because many twentieth-century experts preferred to focus on the artists Hans Holbein and Nicholas Hilliard. Their attributions are less tenuous and their skill more pronounced.

Twenty-first century art historians have the advantage of increasingly sophisticated technology to help date paintings and uncover underlying strokes to identify a given hand. In addition, many primary documents are accessible online, which makes locating records specific to a given artist easier than ever.

Paintings by Levina Teerlinc are still out there, somewhere—perhaps in private collections, perhaps wrongly attributed to Nicholas Hilliard or some other artist. The task at hand is to keep looking at paintings. Use evolving technology to accurately date them. Assess how they were painted. Continue to peruse the pages of sixteenth-century annals for clues about where these artists lived and worked, how much they were paid, with whom they collaborated, and who their patrons were. Like the Ghent-Bruges school of illumination, collaboration is also key among today’s educators, historians, and curators. Working in tandem with literary, social, economic, musical, and political experts can help us recreate the world in which these artists lived and, in the process, identify the works that they created.

Prior to her retirement, Louisa Woodville taught medieval art history at George Mason University. She was also an adjunct professor at the University of Maryland, Trinity College in Washington DC, and at Northern Virginia Community Colleges. In the past decade she has lectured on medieval art for Smithsonian Associates including: the socio-economic agenda of rulers’ artistic programs in twelfth- and thirteenth-century Norman Sicily; sacred texts, the literature of art and faith; and a four-session lecture on pilgrimages that covered Santiago de Compostella, Rome, Jerusalem, and Canterbury. She is writing a book about Simon Bening of Bruges and his family. The study covers the life and career of his daughter Levina Teerlinc, a highly-paid member of the Tudor court and a gentlewoman of the Privy Chamber, from whom monarchs Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary Tudor, and Elizabeth I all commissioned miniatures, manuscripts, and designs.

Other Art Herstory blog posts you might enjoy:

The Lost Works of Susanna Horenbout, Female Artist at the Tudor Court, by Sylvia Barbara Soberton

Susannah Penelope Rosse: Painting for Pleasure in Seventeenth-Century England, by Anna Pratley

A Room of Their Own: Now You See Us Exhibition at Tate Britain, by Kathryn Waters

Mary Beale (1633–1699) and the Hubris of Transcription, by Dr. Helen Draper

Anna Maria van Schurman: Brains, Arts and Feminist avant la lettre, by Maryse Dekker

Books, Blooms, Backer: The Life and Work of Catharina Backer, by Nina Reid

From a Project on Women Artists: The Calendar and the Cat Lady, by Dr. Lisa Kirch

Alida Withoos: Creator of beauty and of visual knowledge, by Catherine Powell

Paper Portraits: The Self-Fashioning of Esther Inglis, by Dr. Georgianna Ziegler

Finding Luisa Roldán: A North American road trip, by Dr. Catherine Hall van den Elsen

“Black-works, white-works, colours all”: Finding Susanna Perwich in her Seventeenth-Century Embroidered Cabinet, by Isabella Rosner

Susanna Horenbout, Courtier and Artist, by Dr. Kathleen E. Kennedy

Gesina ter Borch: Artist, not Amateur, by Dr. Nicole E. Cook

A Clara Peeters for the Mauritshuis, by Dr. Quentin Buvelot

Floral Still Life, 1726—A Masterpiece by Rachel Ruysch, by Dr. Lawrence W. Nichols

Women Artists of the Dutch Golden Age at the National Museum of Women in the Arts

The Protofeminist Insects of Giovanna Garzoni and Maria Sibylla Merian, by Prof. Emma Steinkraus

Brilliant, both substantively and conceptually.

Brava, and thank you.

While I respect any effort to elevate the contributions of female painters in Early Modern England, I feel obliged to point out that many of the contentions in this undocumented piece have been challenged in recent scholarship to the point where they no longer stand. Not the least of such works has been Elizabeth Goldring’s brilliant 2019 biography of Nicholas Hilliard, which explodes for all time the putative connection between Levina Teerlinc and Hilliard. Other works, by, e.g., Katherine Coombs, Graham Reynolds, and myself have further, and I had hoped, definitively, undermined the claims for Teerlinc’s putative oeuvre. It is vital to understand the role of women painters in this and other periods of history, but such an appreciation must surely rest on more secure scholarly footing than we have here.

Robert Tittler, PhD, FRSC, FSA, FRhistS

‘Distinguished Professor of History Emeritus’

Concordia University

Montreal, Qc.

Canada

Dr. Tittler,

I appreciate your comments and agree with of many your points—especially that Elizabeth Golding’s book, which sits here on my lap, is brilliant—as is your Early Modern British Painters Data Base c. 1500-1640. Thank you for this indispensable resource!

But back to Golding, my head nodded last month when got to p. 77, “The reality is that there will probably always be substantial gaps in our knowledge of Teerlinc and others active in producing miniatures in London in the 1560s.” (btw, I did write in my article, “We don’t know whether Teerlinc ever met Hilliard, let alone worked with him.”)

Katherine Coombs, whom you mention, ironically was one of the experts who helped and encouraged me when I met her ten years ago at the Victoria & Albert. Derek Adlam was another, at the time curator at the Portland Collection.

Other curators and experts … well, not so much. To the extent that I set aside this Teerlinc research aside for ten years as it was impossible to definitely ascribe any painting as by her hand. Then—drum roll—I realized, attributing paintings doesn’t have to be set in cement. I did write, “So how can we confidently attribute any painting, let alone these, to Teerlinc? Until we find more documentary sources that leave no doubt, we cannot.”

Does that mean abandon ship? No, it means change course. What I set out to do, and succeeded in that you responded, is to encourage dialogue among experts and scholars—to keep looking together, reading, assessing, and especially sharing knowledge with across disciplines and oceans.

~ Louisa Woodville

Well, there’s always hope of new discoveries! Keep plugging, and good luck!

Robert Tittler

My MA thesis on the topic of Levinia Teerlinc and Queen Elizabeth I if you are interested. https://etd.ohiolink.edu/apexprod/rws_olink/r/1501/10?clear=10&p10_accession_num=ucin1116614443