Guest post by Mary Creed, The Morgan Library & Museum

Painter of the King’s Garden

This week—September 6, specifically—marks the 241st anniversary of the death of Madeleine Françoise Basseporte (1701–1780), one of the highest ranking botanical artists in France. She was born in Paris, and began her early artistic career in portraiture. She may have been taught by the Venetian Rococo painter Rosalba Carriera (1714–1757). Basseporte’s aptitude for pastel can be appreciated in the possible self-portrait shown above, which was once attributed to Carriera. (Fig.1)

She shifted from portraiture to natural history illustration in 1726, training with Claude Aubriet (1665–1742), the official painter of Louis XV’s garden. By 1735 she received the right to succeed Aubriet, becoming the first woman to hold the position, a post which she retained until her death. As part of her role as official painter of the King’s garden, Basseporte was obliged to contribute to Les Vélins du Roi (The King’s Vellums), a codex of plant and animal illustrations started in 1631 to document specimens from the royal collection. Basseporte also worked for the King’s official mistress, Madame de Pompadour, who influenced the King’s interest in supporting the science of horticulture.

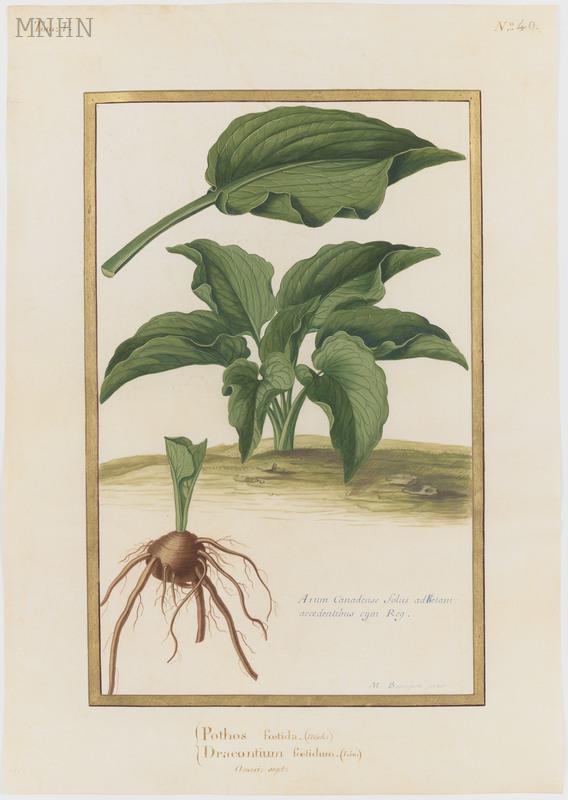

Many of Basseporte’s illustrations can be categorized by their function. Some drawings appear to have a higher degree of scientific intention. Her labeled illustration of wild ginger, for example, emphasizes structure and classification of a single specimen (Fig. 2). It seems that the more informal illustrations, containing multiple plants, ribbons, and insects, served as personal commissions from patrons such as Madame de Pompadour (Fig. 3; see also Fig. 6, below).

The Eclipse of “Tulipmania”

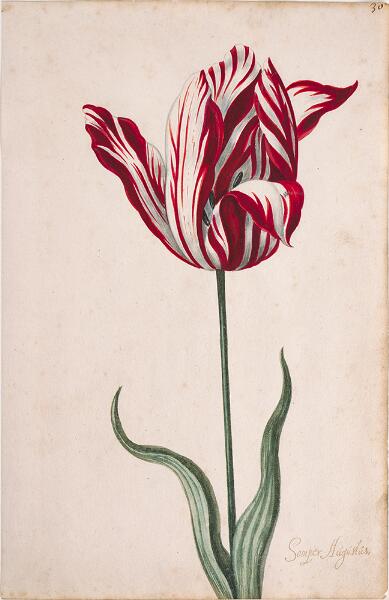

Basseporte secured her position at a time when the popularity of tulips had just begun to give way to the vogue for another bulbous plant—hyacinths. In the seventeenth century, enthusiasm for Dutch tulip bulbs skyrocketed. Prices for “broken” tulips, in which a virus caused color striations in the petals, were unprecedented. A single bulb of the Semper Augustus could cost the equivalent of a luxurious Dutch townhouse (Fig. 4).

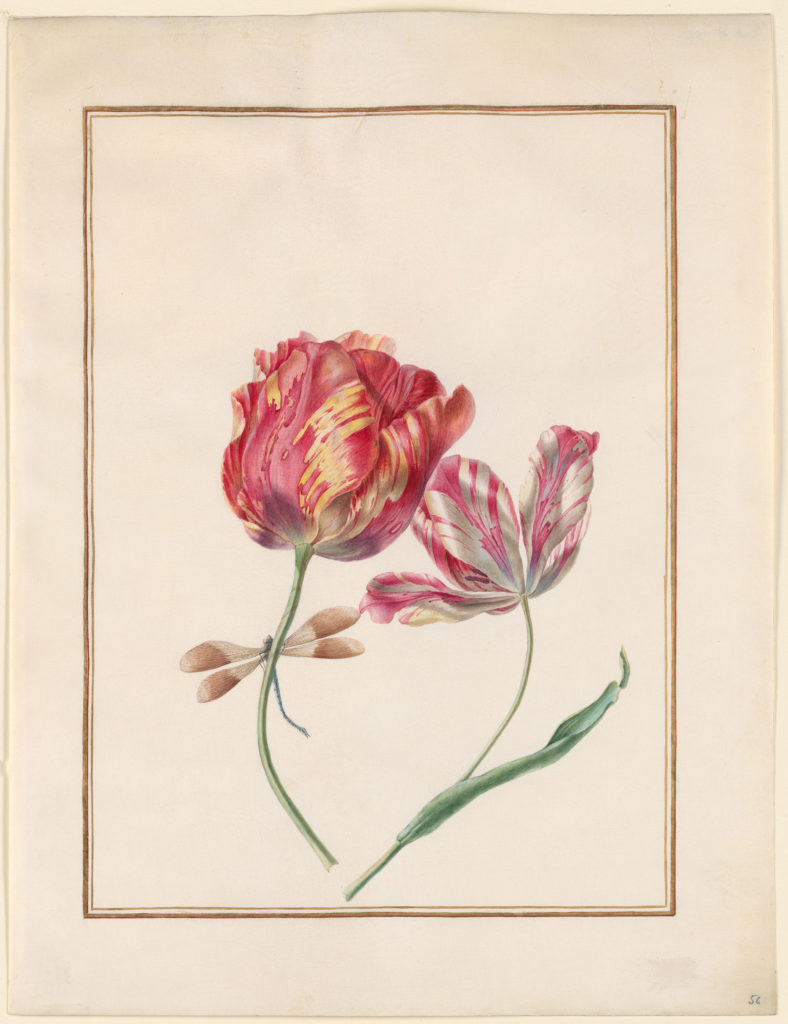

During his reign, Louis XIV had filled the Grand Trianon at Versailles with tulips. A planting plan of 1693 shows three times as many tulips as hyacinths. When Louis XV ascended, tulips remained in the gardens but lost their preeminent place in the display. Basseporte executed several watercolors on vellum of tulips, especially the rare “bizarres,” cultivated to imitate the influential Dutch tulips (Fig. 5).

Basseporte’s Hyacinths

Hyacinths replaced tulips as the object of a flower craze. A record from 1746 documents that the king’s gardeners ordered 403 bulbs of hyacinths of twenty-five varieties for the extensive hyacinth garden. The fashionable heights hyacinths reached can be attributed in large part to Madame de Pompadour. Her preference for the flower encouraged the king to order these extensive plantings of them in the royal gardens. Madame de Pompadour also likely commissioned Basseporte to illustrate her favored flowers.

In a sheet from an album at the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Basseporte expertly renders the rare double hyacinth. The periwinkle hyacinth stalk is illustrated on the right (Fig 6). The densely packed bell-shaped blooms contain an extra layer of petals, hence the name double hyacinth, a new cultivation prized in the eighteenth century.

While her rendition is scientifically precise, she prioritizes aesthetic considerations. Basseporte experiments with the color combination of the two flowers, and adds decorative elements such as the pink ribbon. A butterfly takes up residence in the lower left of the frame, and the observant viewer will notice the barely discernible spider, who is suspended by ultra-thin strands from the flower. The tiny trompe l’oeil spider is a jocular detail Basseporte repeats in other compositions of this kind (Figs. 7, 8).

Fig. 8 (right). Madeleine Françoise Basseporte, Detail of Bizarre carnations, ca. 1750. Watercolor on vellum. The Morgan Library & Museum.

There is a similar sheet in a disassembled album held at The Morgan Library & Museum. Basseporte illustrates the pink variety of the double hyacinth with its illustrious green leaf that extends down, as if still attached to its bulb, just out of frame (see Figure 4 above). The multiple angles and meticulous details of the plant demonstrate Basseporte’s ingenuity in delivering a scientifically accurate illustration while also producing a drawing that is exquisite to behold. However, Madame de Pompadour’s interest in the structure and hidden components of plants should not be discounted.

Madame de Pompadour’s Interior Botanicals

Madame de Pompadour became fascinated with the practice of “forcing” hyacinth bulbs to bloom indoors. This could be achieved by planting the bulb in a stemmed vase above water so that the roots would develop in it (Fig. 9).

In effect, the translucent glass allowed the viewer to witness the growing roots, much like the scientific botanical illustrations by Basseporte (see Fig. 4 above). In 1759, Madame de Pompadour had as many as 200 hyacinths on display indoors in this manner. Growing bulbs soon became fashionable with the elite in, and outside of, France.

Backed by the support of Louis XV and Madame de Pompadour, the Sèvres porcelain manufacturer moved near Madame de Pompadour’s Bellevue Palace in 1756. In that same year, Sèvres began making ceramic bulb pots with hollow bases that were to be filled with water and topped with fitted circular bulb holders with pierced collars. It was likely Madame de Pompadour’s specific interest in growing hyacinth bulbs indoors and her patronage of the factory that spurred production of these pots.

This pair of Sèvres porcelain vases with holes on the base intended for hyacinth bulbs was displayed on the mantelpiece in her bedroom (Fig. 10). Madame de Pompadour was perhaps drawn to this particular form of display as a result of her exposure to the botanical illustrations from artists such as Basseporte.

Basseporte’s ‘objets de luxe’

Basseporte also decorated ‘objets de luxe’, or, objects of luxury, which included textiles and porcelain. This was a common practice among many of the royal court painters, although many of these ornamentations were unsigned. It is unknown which, if any, of the ceramics were painted by Basseporte. On the other hand, many artists of the Sèvres factory made designs based on botanical illustrations by royal court painters. For example, Sèvres artist Moïse Jacobber (1818–48) made copies from Gérard van Spaendonck (1746–1822), Basseporte’s successor as official painter of the king’s garden. Spaendonck’s hyacinths show an indebtedness to Basseporte’s legacy (Figs.11, 12).

Fig. 12 (right). Gerard Van Spaendonck, Jacinthe double (Double hyacinth), 1800. Watercolor on vellum. Private collection.

It is not unreasonable to assume that some of Basseporte’s botanical illustrations would have also been used to decorate ceramics. It is also believed that Basseporte worked for a period as Madame de Pompadour’s interior decorator. Basseporte occupied an esteemed position as both a scientific illustrator and decorator. She contributed to the decorative arts and strengthened the connection between the fluid boundaries that separate botanical illustration and ornament.

The demand for hyacinths prevailed throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The preference shifted from double to single hyacinths, which are depicted here by Basseporte and her possible student Vallayer-Coster (Figs. 13, 14).

Fig. 14 (right). Anne Vallayer-Coster, White hyacinth, ranunculus and anemones, n.d. Watercolor. Private collection.

The forcing of bulbs on water continued to be a popular way of having spring flowers indoors in the cold and dark winter period. The porcelain bulb pots continued to be manufactured in France and inspired many variations across the Channel in England.

Imperial Power and Exotic Horticulture

Hyacinths are indigenous to Asia Minor, and were imported to Europe in the 1680s. Their scientific name, Hyacinthus orientalis, references this origin. Many of the plants that sprouted in royal gardens were native to Asia, Africa, and the Americas. Botany has a complex historical relationship with colonialism. The systems of classification, cultivation, and marketing of plants from non-European countries occurred in conjunction with foreign conquests.

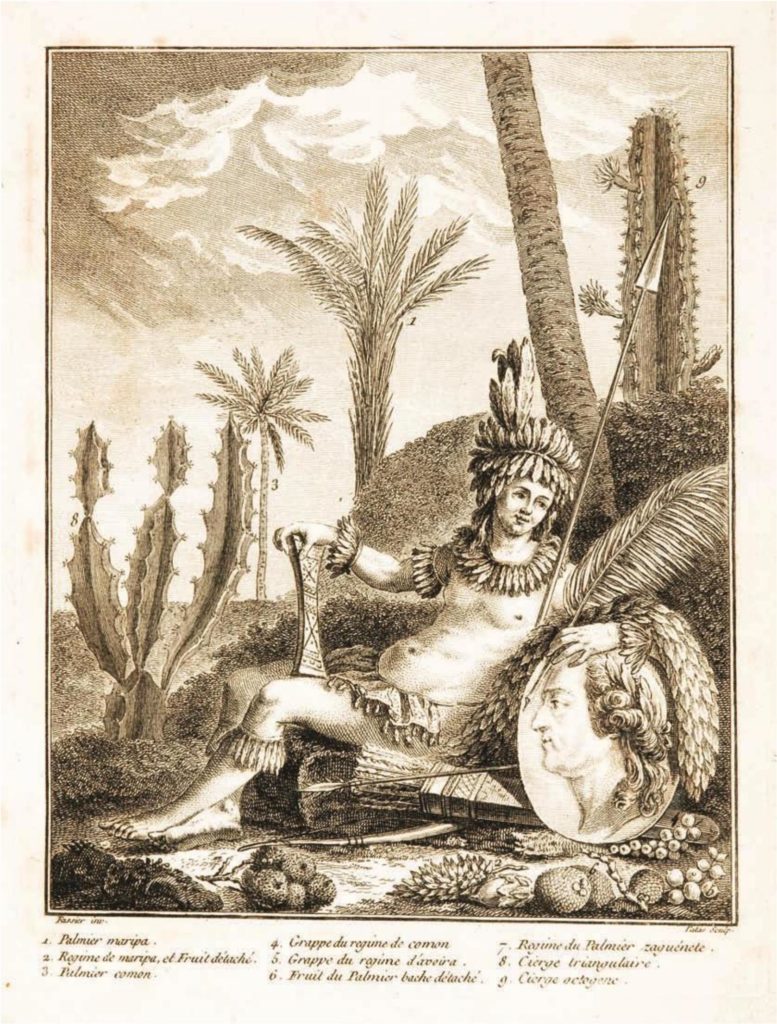

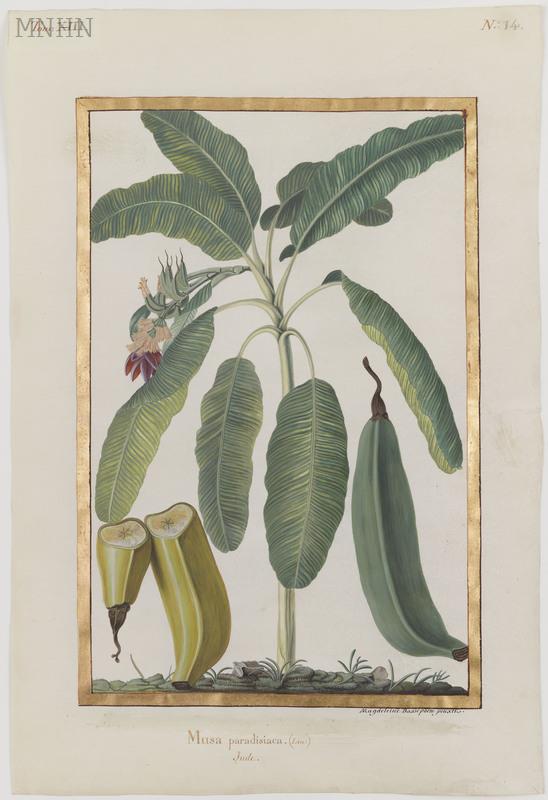

This engraving (Fig. 15) of the personification of America, cradling a medallion with the portrait of the botanist Jean Baptiste Fusée Aublet (1720–78), demonstrates the romanticized notion of expeditions in the eighteenth century. Precious spices, fruits, and herbal medicinal plants such as cinnamon, sugar, tea, bananas, and cloves were primary motivators for imperial expansion. Basseporte painted the Musa paradisiaca L. India plantain banana, which is native to Southeast Asia, especially in regions of India, as the given taxonomy indicates (Fig. 16). In reference to the forbidden fruit of paradise, “paradisiaca” means “belonging to paradise.”

The French royal gardens acted as a hub to fulfill these royal colonial ambitions. Natural history illustrations can easily be perceived as an apolitical genre, with no narrative or moralizing intention. Yet the essential function of the king’s garden was to exploit the resources of foreign plants, and the classification, naming, and documentation of the received specimens from around the world represented the power of the monarchy to exert control over nature, and its geographical dominion. An appreciation of the cultural history of plants, and the complex relationship of science and colonial expansion, contributes to a deeper understanding of Basseporte’s botanical paintings as objects of rich historical and artistic importance.

A Lasting Legacy

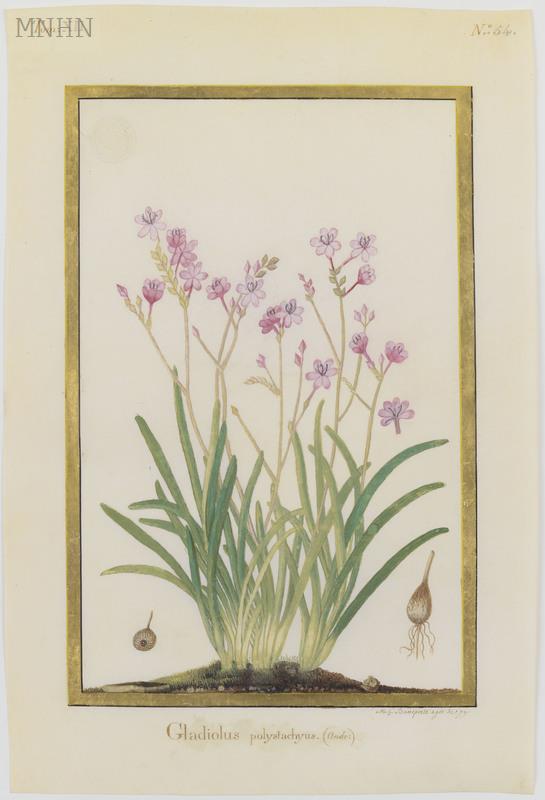

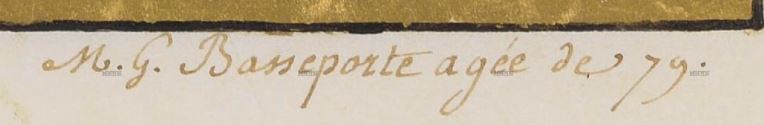

Basseporte taught several important women of science, including anatomist Marie Marguerite Biheron (1719–1795) and possibly the botanical illustrators Anne Vallayer-Coster (1744–1818) and Marie-Thérèse Reboul (1738–1806), in addition to both daughters of Louis XV. Basseporte enlisted orphaned women as assistants; she left art supplies to these women in her will. Age did not slow her down. By the time she was 77 years old Basseporte started signing her age alongside her signature, perhaps in a rejection of ageism and to mark her assiduous commitment to her craft.

Basseporte’s contributions to botanical illustration, decorative arts, and interior design merged at the intersection of science, art, and commerce. Basseporte’s biographer, the philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, said of her botanical illustrations that, “nature gave existence to plants, but… Mademoiselle Basseporte preserved it for them.” This sentiment remains applicable to our appreciation of Basseporte today: her illustrations serve as testament to her legacy of scientific, artistic, and material cultural history, as well as works of art to enjoy and reflect upon.

Mary Creed is The Morgan Library & Museum Zukerman Departmental Assistant in the Department of Drawings & Prints. She earned her master’s degree in Art History with a concentration in Museum Studies at the City College of New York. She specializes in women and LGBTQIA artists who have been historically under- or misrepresented, such as Marie Laurencin, Elisabeth Jerichau-Baumann, and Romaine Brooks. She has completed research internships at The Metropolitan Museum of Art and The Barnes Foundation.

Other Art Herstory posts to do with women natural history illustrators:

Rachel Ruysch: The Art of Nature, by Stephanie Dickey

Louise Moillon: A pioneering painter of still life, by Lesley Stevenson

Rachel Ruysch’s Vase of Flowers with an Ear of Corn, by Lizzie Marx

Madeleine Françoise Basseporte and the Ribbon as a Signifier of a “Woman’s Touch,” by Tori Champion

Women and the Art of Flower Painting, by Ariane van Suchtelen

Barbara Regina Dietzsch: Enlightened Flower Painter, by Andaleeb Badiee Banta

Books, Blooms, Backer: The Life and Work of Catharina Backer, by Nina Reid

Curiosity and the Caterpillar: Maria Sibylla Merian’s Artistic Entomology, by Kay Etheridge

Alida Withoos: Creator of beauty and of visual knowledge, by Catherine Powell

Floral Still Life, 1726—A Masterpiece by Rachel Ruysch, by Lawrence W. Nichols

The Protofeminist Insects of Giovanna Garzoni and Maria Sibylla Merian, by Emma Steinkraus

Women in Zoological Art and Illustration, by Ann Sylph, Librarian of the Zoological Society of London

Other Art Herstory posts to do with French women artists:

Blanche Hoschedé-Monet: An Artist in Her Own Right, by Rebekah Hoke Brown

Unpacking the Exhibition: Blanche Hoschedé-Monet in the Light, by Haley S. Pierce

Charlotte Eustache Sophie de Fuligny-Damas, Marquise de Grollier, by David Pullins

Exhibiting Women: The Art of Professionalism in London and Paris, 1760–1830, by Paris Spies-Gans

Marie Laurencin and the Autonomy of Self-Representation, by Mary Creed

The Many Faces of Suzanne Valadon, by Suzanne Singletary

Marie-Thérèse Reboul Vien: Finding the Natural in the Neoclassical, by Tori Champion

Adélaïde Labille-Guiard: Artist, Friend, Teacher, by Jessica L. Fripp

Marie-Guillemine Benoist, Revolutionary Painter, by Paris Spies-Gans

Seductive Surfaces: Anne Vallayer-Coster’s Vase of Flowers and Conch Shell at the Met, by Kelsey Brosnan

The Theatrical Wonders of Jeanne Paquin’s Belle Époque Parisienne, by Julia Westerman

Victorine Meurent, More than a Model, by novelist Drēma Drudge

Paper Portraits: The Self-Fashioning of Esther Inglis, by Georgianna Ziegler

Thank you for this! I liked Basseporte’s work, and this taught me even more interesting things.