by Erika Gaffney with Cara Verona Viglucci

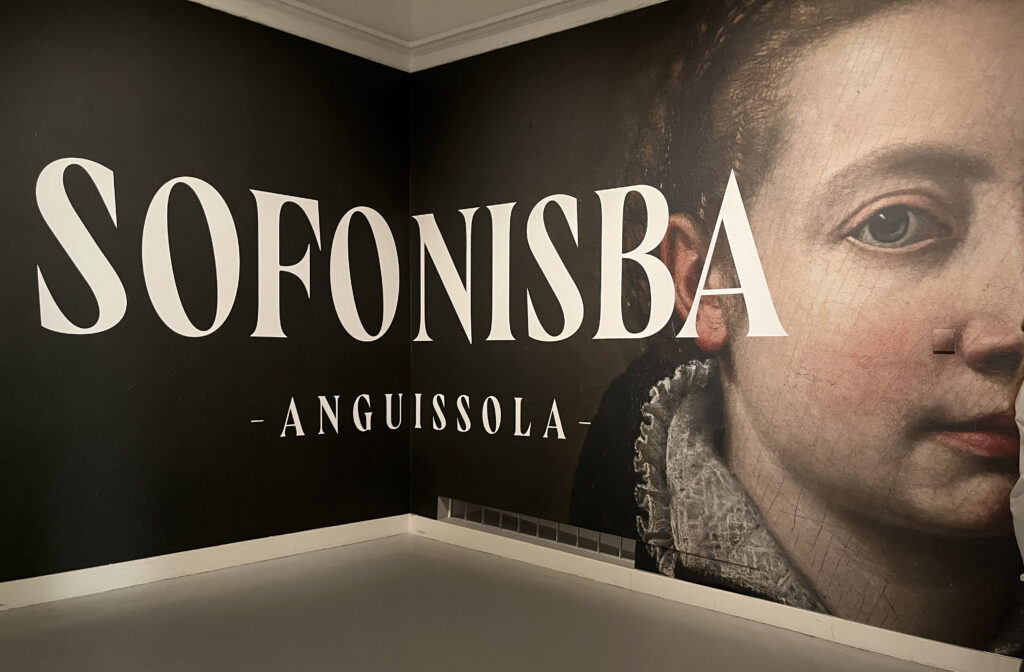

Of the twenty-one paintings on display at Rijksmuseum Twenthe in the exhibition Sofonisba Anguissola: Portraitist of the Renaissance, eighteen are by the featured artist, Sofonisba Anguissola (c. 1532–1625). The other three portraits are by the artist’s sisters: two are by Lucia Anguissola (c. 1536–c. 1565), and one is by Europa Anguissola (c. 1542–c. 1578). Almost all of the paintings are solo or group portraits. The exceptions are four paintings that focus on religious themes. Loaners include institutions and collectors from around Europe, including Italy, Denmark, Poland, the UK, France, Spain, and Hungary; there is also one painting on loan from a museum in the United States.

Exhibition format

The artworks are displayed in a single, large room. Many of the paintings are mounted on the room’s four walls. Additional wall surface is supplied in the form of room dividers. One advantage of the display space is that it is possible to see every painting from both far away, and up close. (In fact, it is possible to get quite close to each painting. In most cases, the only feature separating viewers from the art is a small, moat-like gap between the flooring and the wall. There are only two paintings that, at the request of the loaning institution, have spacers installed in front of the work. But even these spacers are unobtrusive.)

Another advantage is that the viewer is not a prisoner of flow from one gallery to another. If there’s a group of admirers in front of one particular work, one can easily migrate to a painting in a less populated section of the room. And then one can easily move back to the earlier painting, once the crowd around it has cleared.

Self-portraits

According to the Museum of Fine Arts Boston website, Sofonisba Anguissola “executed more self-portraits than any other artist in the period between Dürer and Rembrandt.” This show features five of about sixteen extant Sofonisba self-portraits, all dated within the period c. 1555–61, when the painter was in her 20s. Among them is Bernardino Campi Painting Sofonisba Anguissola, which has inspired considerable discussion and debate among art historians.

As Natasha Moura describes in a post in her Women’n Art blog, scholars are divided about whether this is a self-portrait in which the artist playfully honors her teacher, or a portrait by Campi of one of his most famous students. So, it may or may not qualify as a self-portrait; in the exhibition, the placard attributes the work to Campi.

Friends and family

Family

Many of the portraits collected here are of family members. Among those by Sofonisba are:

- her now iconic painting of her sisters playing chess;

- a portrait of their father, Amilcare, with her sister Minerva and her brother Asdrubale;

- her sister Elena depicted in white nun’s garb; and

- a close-up painting of the face of a male relative called Archimede Anguissola

Also in this group is a small painting by Lucia of the head and shoulders of their sister Europa. There is another a painting by Europa, of her mother-in-law Bianca Schinchinelli. It is only during the course of this exhibition that Europa has been recognized as the author of the latter work. It was formerly attributed to “the circle of the Anguissola sisters.” This Art Daily article describes art historian Michael Cole’s detective work to identify the artist and the sitter.

Friends

Among the works painted in the 1550s are portraits of men—named and unnamed—by Sofonisba and Lucia Anguissola. The two named sitters are prominent citizens of the Anguissolas’ hometown, Cremona. Presumably, all four of them are friends of the family. The wall text explains that to preserve their reputations, the artists would have painted male subjects only in the presence of a chaperone. The inscriptions of at least two of these portraits indicate that the sisters’ father Amilcare served in this role.

The show includes portraits of the daughters of Philip II of Spain and Elisabeth of Valois, as children. Sofonisba portrayed them during her time as a lady-in-waiting at the Spanish court. While they are not quite friends or family members, Sofonisba did develop relationships with Isabella Clara Eugenia and Catalina Michaela. She connected with each of them with again later in life, after each had married.

Religious art

Of the four religious paintings, most date from the time of Sofonisba’s return to Italy, after she departed from the Spanish court. Two of these artworks took me by surprise: The Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine, and Holy Family with Saints John the Baptist and Francis of Assisi.

I had seen onscreen and/or read about many of the works in this exhibition. Some of them I’d even seen “in person” previously. But I had only ever seen these two paintings in the catalog for the Prado’s 2018 exhibition A Tale of Two Women Painters. The installation photo below conveys the small size and intimacy of the latter artwork.

What’s in a name? Signatures

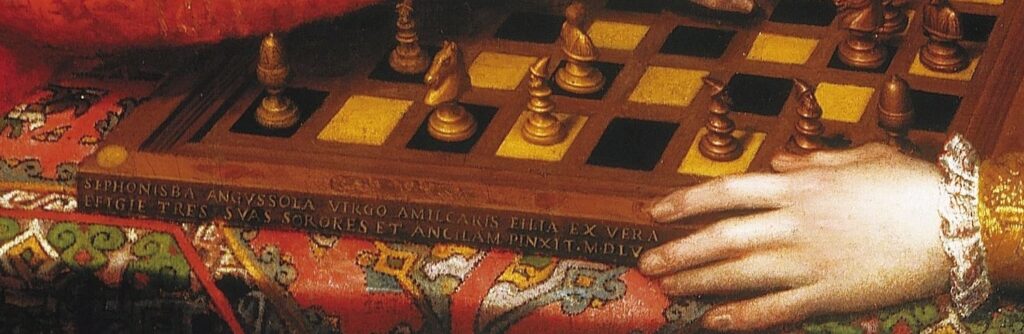

When walking through the exhibit, it is fascinating to observe the many ways in which Sofonisba signed her artworks. The variations include, but are not limited to: Sophonisba Anguissola, Sofonisba Anguissola, and Sephonisba Angvssola. Some signatures can be found just next to the figures whose portraits have been painted, while others are found in more creative spaces such as on a scroll beneath a dog’s paw or on the side of a chessboard.

A few paintings, however, lack any signature at all, which in at least some cases is because of the practices in the Spanish royal court. These alterations in form provide a kind of scavenger hunt for the viewer, if they are so inclined to participate.

Beyond paintings

Contextual materials

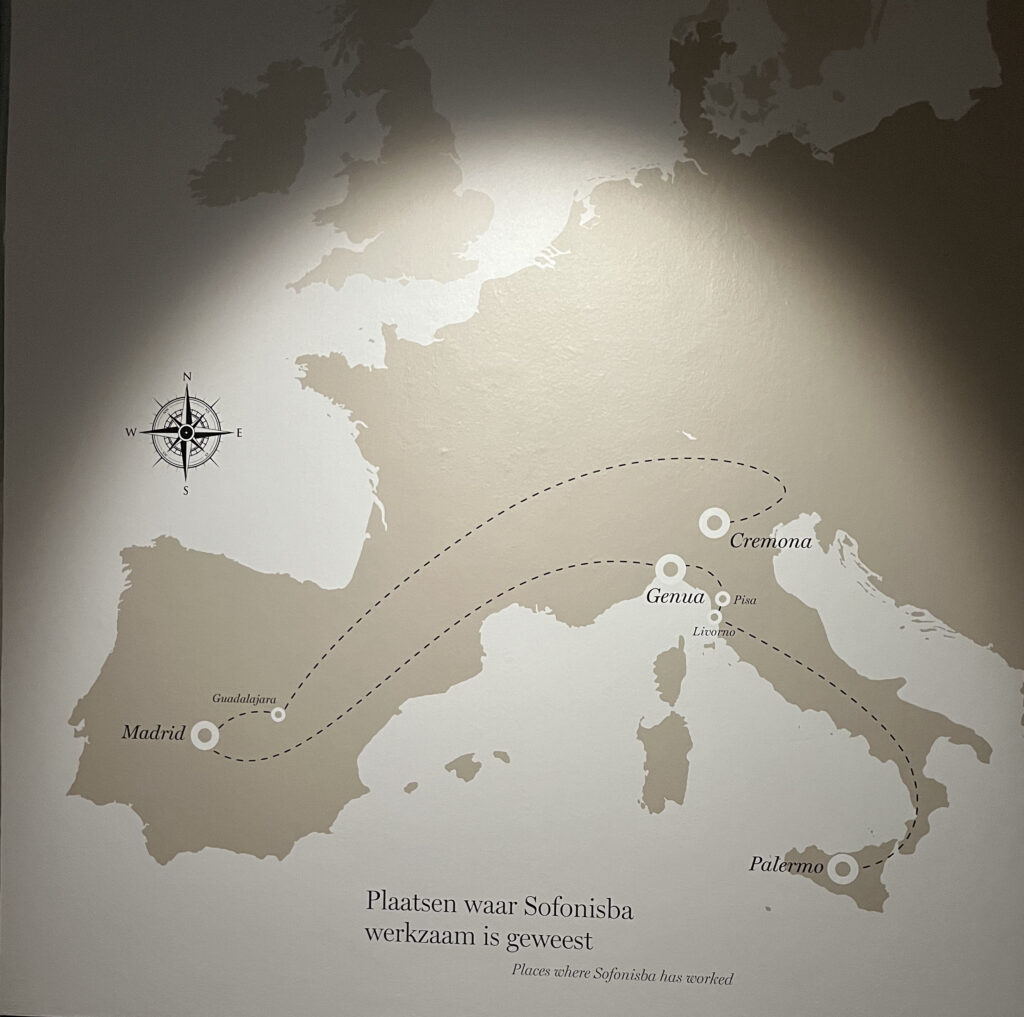

The organizers of Sofonisba Anguissola: Portraitist of the Renaissance thoughtfully include objects and murals to provide context for the art. Examples of material culture include a spinet and a musical instrument that might be a lute. There is also a copy of Baldassare’s The Book of the Courtier (1538). An oversized wall mural reproduces Sofonisba’s drawing of a crying boy bitten by a crawfish or lobster.

And there is a large-scale map depicting the scope of the artist’s travels: from her youth in Cremona; to her service in Madrid; to Palermo, where she lived with her first husband, Fabrizio Moncada; to the home in Genoa where she lived for some thirty-five years with her second husband, Orazio Lomellini; and finally back to Palermo, where she and Orazio moved together, and where she is likely buried.

Collateral to the display

At the practical level, the lighting seemed especially good. One could view the paintings from almost any distance or angle without too much glare. While I did not elect to use headphones, there were audio guides available in at least half a dozen languages. In the gift shop, there’s a Sofonisba wine on offer! This is a form in which I’ve never before seen an artist celebrated.

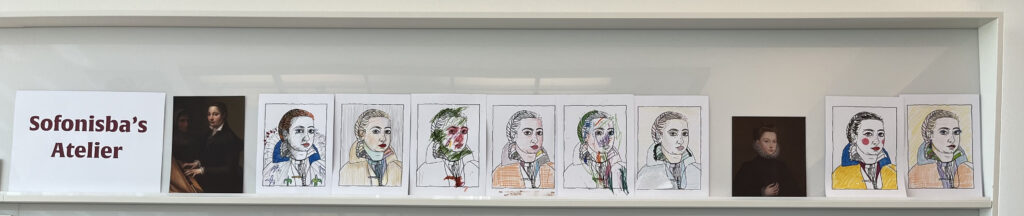

In the café, the museum displays Sofonisba portraits colored by visitors over the course of the show.

Conclusion

The art-going public has been fortunate in recent years to have access to a concentration of Anguissola paintings. When is it likely that so many works by Sofonisba Anguissola will be gathered together in one place again? This is a jewel of a show. It displays gorgeous 500-year-old paintings in a way that is accessible and enjoyable for non-specialists as well as historians. As one visitor observed, “There is so much publicity around the collection in one place of twenty-seven works by Vermeer. But the bringing together of twenty-one works by the Anguissola sisters is at least equally remarkable. Whoever organized this exhibition deserves a lot of credit.”

If you have the opportunity, do experience Sofonisba Anguissola: Portraitist of the Renaissance before it closes. (But for anyone who isn’t able to make it, there is this to look forward to: a terrific volume about the artist is due out in April 2024 in the book series Illuminating Women Artists!) The museum is within easy walking distance of the train station. And don’t leave Rijksmuseum Twenthe without visiting the Sottobosco Garden, designed by visual artist and photographer Elspeth Diederix.

Erika Gaffney is Founder of Art Herstory. Follow Erika on Twitter, LinkedIn and Facebook. Cara Viglucci is a student at McGill University, minoring in Art History. Follow Cara on LinkedIn.

Sofonisba Anguissola: Portraitist of the Renaissance is on at Rijksmuseum Twenthe through Sunday, June 11. The show is a collaboration between Rijksmuseum Twenthe and Nivaagaard Malerisamling. The Nivaagaard version of the exhibition ran from September 23, 2022 to January 15, 2023 under the title Sofonisba—History’s Forgotten Miracle.

Art Herstory has a Sofonisba Anguissola resource page. Scroll all the way down for a list of books (fiction and non-fiction) and articles about this artist!

More Art Herstory exhibition reviews:

Dutch and Flemish Women Artists—A Major Exhibition at the National Museum of Women in the Arts, by Erika Gaffney

Rachel Ruysch at Munich’s Alte Pinakothek, by Erika Gaffney

Female Artists and their Remarkable Careers: An Appeal to Rethink Art History, by Jenny Körber

Roma Pittrice: Women Artists at Work in Rome Between the Sixteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, by Alessandra Masu

Making Her Mark Leaves its Mark at the Art Gallery of Ontario, by Isabelle Hawkins

Early Modern European Women Artists at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, by Erika Gaffney

Making Her Mark, An Essential Corrective in the History of Art, by Chadd Scott

Masters and Sisters in Arts, by Jitske Jasperse

Reflections on Making Her Mark at the Baltimore Museum of Art, by Erika Gaffney

Sofonisba Anguissola: Portraitist of the Renaissance at Rijksmuseum Twenthe, by Nelleke de Vries

Rosa Bonheur—Practice Makes Perfect, by Ien G.M. van der Pol

Thoughts on Feminist Art History in the Wake of Artemisia: Vrouw & Macht at Rijksmuseum Twenthe, by Jitske Jasperse

Thoughts on By Her Hand, the Hartford Iteration, by Erika Gaffney

Plautilla Bricci: A Painter & “Architettrice” in Seventeenth-century Rome, by Alessandra Masu

“La grandezza del universo” nell’arte di Giovanna Garzoni / “The grandeur of the universe” in the art of Giovanna Garzoni, by Dr. Sara Matthews-Grieco

In defense of monographic exhibitions of female artists: The case of Fede Galizia, by Camille Nouhant

The Ladies of Art are in Milan, by Cecilia Gamberini

A Tale of Two Women Painters, by Natasha Moura

“Artemisia” at the National Gallery: A Review, by Sheila McTighe

Wonderful review Erika.

Just now I was able to visit the exhibition – just in time!