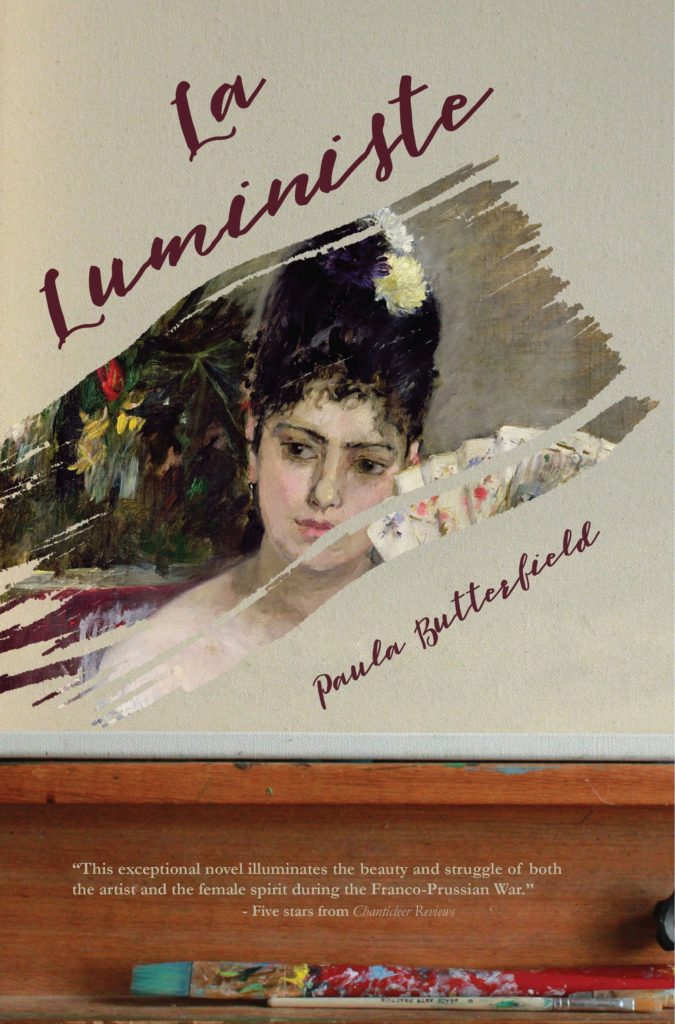

Guest post by Paula Butterfield, author of La Luministe and other works of historical fiction

Years after their brief affair, musician Evans Herman wrote a nostalgic poem for Joan Mitchell, A Gift of Violets. Mitchell reciprocated with a small drawing of violets. Not an earth-shaking exchange, except for how it parallels an event in Berthe Morisot’s life. After she modeled for a painting for Edouard Manet, he sent her a small painting of the violet nosegay she’d worn pinned to her dress that day. These minor episodes hint at how much Morisot and Mitchell, two women artists who lived and worked at a remove of one hundred years, had in common.

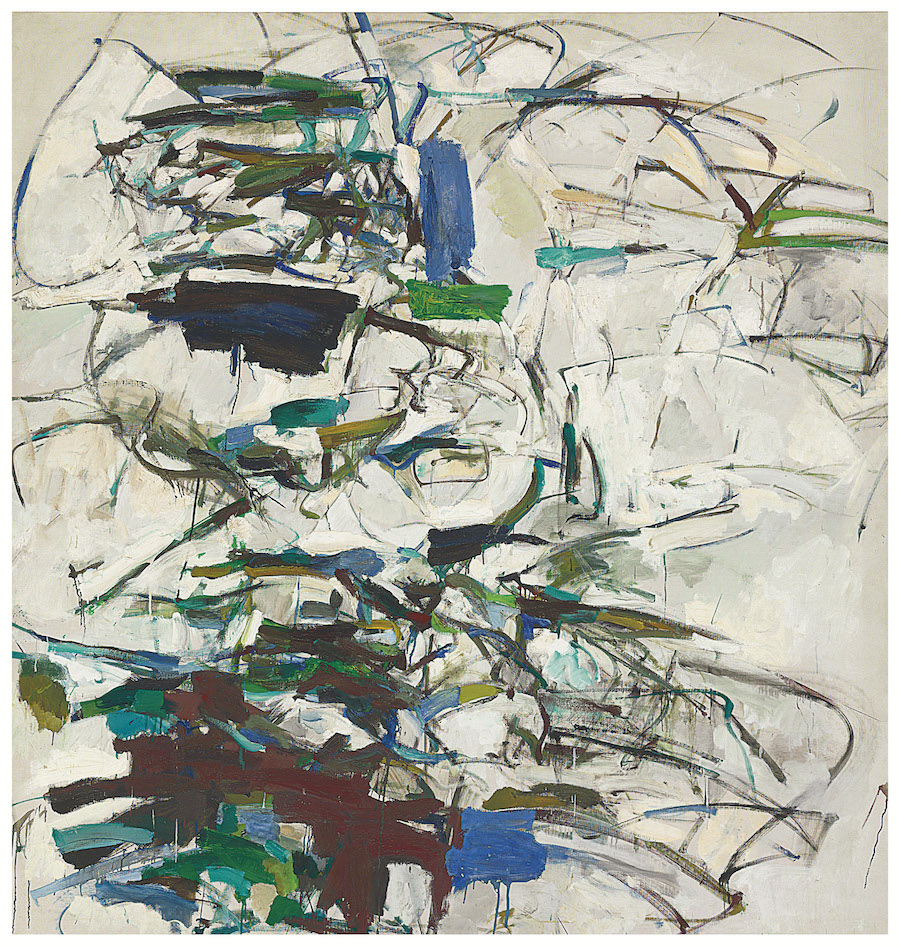

As I researched Berthe Morisot for my historical novel, La Luministe, I saw elements of this Impressionist artist’s work that hinted at Joan Mitchell’s future paintings. The brushstrokes on Morisot’s unfinished canvases, in particular, look like the work of the Abstract Expressionists of the 1950s. (See the right side of Woman at Her Toilette, above.) As art critic Sam Smee has written, “In the 1880s, Morisot experimented with unprimed canvases and a lack of finish that looks radical even today — closer at times to Joan Mitchell than Paul Cézanne.” (Washington Post, August 21, 2018)

In turn, painter Joan Mitchell was labeled an “Abstract Impressionist.” It was a term coined by Elaine de Kooning, who conflated the Impressionists’ interest in the optical effects of nature with the Abstract Expressionists’ interest in the visual representations of emotional or spiritual states. De Kooning compared Mitchell to Monet in her use of watery surfaces and reflections of the sky. From the 1970s until the end of her life, Mitchell even lived in a house next to Monet’s former home in Vetheuil.

Morisot and Mitchell both lived in France, both came from well-off upper-class families, and both were involved in difficult relationships with well-known artists—Morisot with Edouard Manet and Mitchell with Jean-Paul Riopelle. And each artist had great feeling for landscape, especially trees. Morisot, as one of the founding Impressionists, painted en plein air. She felt sustained by trees.The Bois de Boulogne, “the lungs of the city”, was her refuge from modern Paris, and the forested park provided the setting for many of her paintings. Mitchell felt an affinity for trees, as well. When she was in the hospital recovering from hip surgery late in her life,

… they moved me to a room with a window and suddenly … I saw two fir trees in a park … and I was so happy. It had to do with being alive, I could see the pine trees, and I felt I could paint. (from an interview with Yves Michaud for catalog, Joan Mitchell: New Paintings, 1986)

Green blotches traverse a neutral background in both fauna-filled canvases, below. The pink figure on the right in Harvest à Bougival serves as an accent comparable to Mitchell’s perfect fuchsia-colored accent in roughly the same position in My Plant.

Private collection; source, Artsviewer.

Do you see what I mean? In the paintings below, there are similarities in composition (emphasis in lower-left corner), brush strokes (as scumbled and breezy as the wind at the English seaside), and palette (muted blue-grays with accents of red in Morisot’s painting, with green and blue accents in Mitchell’s painting).

(also known as Harbor Scene, Isle of Wight), 1875.

Newark Museum(?); source, The Athenaeum.

Private collection; source, Christie’s.

In 2014, an untitled work of Joan Mitchell’s brought $11.9 million at auction, the highest price garnered by a woman artist to date—supplanting the $10.9 million brought by Berthe Morisot’s After the Luncheon in 2013. It’s appropriate that Morisot and Mitchell topped the list of most valued women artists in two consecutive years. Separated by a century, the artists shared not only lives lived in France and devotion to their art, but also a way of seeing.

I hope you’ll now be looking for similarities in paintings you see by these Abstract Impressionists. Show me what you find—contact me, @pbutterwriter or at paula-butterfield.com.

After developing and teaching college courses about women artists for many years, Paula Butterfield turned to writing about them. La Luministe, her debut novel (Regal House, 2019) about Impressionist Berthe Morisot, won a first place Chanticleer Reviews Chaucer Award for historical fiction. Paula lives with her husband and daughter in Portland, Oregon, where she is working on her next book about two rival American artists.

Order this book from the publisher, Regal House.

More Art Herstory blog posts you might enjoy:

Blanche Hoschedé-Monet: An Artist in Her Own Right, by Rebekah Hoke Brown

Unpacking the Exhibition: Blanche Hoschedé-Monet in the Light, by Haley S. Pierce

The Cheerful Abstractions of Alma Thomas, by Alexandra Kiely

Material Re-Enchantments: A Review of Remedios Varo: Science Fictions, by Suzanne Karr Schmidt

Marie Spartali Stillman’s The Last Sight of Fiammetta, by Margaretta S. Frederick

Visual Feasts: The Art of Sarah Mapps Douglass, by Erika Piola

Evelyn De Morgan: Painting Truth and Beauty, by Sarah Hardy

Anna Ancher’s Vaccination and Scientific Motherhood, by Alice Price

Marie Laurencin and the Autonomy of Self-Representation, by Mary Creed

The Many Faces of Suzanne Valadon, by Suzanne Singletary

Dalla Husband’s Contribution to Atelier 17, by Silvano Levy

Anna Boberg: Artist, Wife, Polar Explorer, by Isabelle Gapp

Happy Birthday, Fidelia Bridges! by Katherine Manthorne

The Ongoing Revival of Matilda Browne, American Impressionist, by Alexandra Kiely

Esther Pressoir: Imagining the Modern Woman, by Suzanne Scanlan

From a Project on Women Artists: The Calendar and the Cat Lady, by Lisa Kirch

Marie-Guillemine Benoist, Revolutionary Painter, by Paris Spies-Gans

The Life and Art of Dorothea Tanning, by Victoria Carruthers

Victorine Meurent, More than a Model, by Drēma Drudge

Talking Artemisia Gentileschi with Joy McCullough, Author of “Blood Water Paint”

Gesina ter Borch: Artist, Not Amateur, by Nicole Cook)

The Protofeminist Insects of Giovanna Garzoni and Maria Sibylla Merian, by Emma Steinkraus)

For the complete list of Art Herstory blog posts, visit this link