Guest post by Christina K. Lindeman, University of South Alabama

Anna Dorothea Therbusch, born Anna Dorothea Lisiewska on July 23, 1721, is not a household name. However, her work has been recognized and inserted into the art historical canon by the previous generation of feminist art historians: Ann Sutherland Harris, Linda Nochlin, Rozsika Parker, and Griselda Pollock. These scholars introduced Therbusch to an English-speaking audience, noting the challenges Therbusch faced to become a history painter, due to her lack of academic training. In Parker and Pollock’s Old Mistresses: Women, Art and Ideology, published in 1981, the caption next to Therbusch’s stunning self-portrait with monocle stated “Her oeuvre contains few major subject pictures; she concentrated on portraiture, for she never had the opportunity to study anatomy sufficiently to fulfil her ambitions as a history painter.”

Yet, during her lifetime Therbusch had a reputation of being a history painter. We should remember that in 1767, on her admission into the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture in Paris, the French journal the Mecure de France announced that she was “a famous painter of history”—not a portraitist.

Early Life and Training

Although we know few details about Therbusch’s early life, we can surmise that she was trained by her father Georg Lisiewsky a portraitist for the Prussian court. The eighteenth-century writer and publisher Friedrich Nicolai described Lisiewsky as “a good portrait painter whose talent had to thank for his own diligence….” One could assume that he imparted his training as a portraitist to his artist children: Christian Friedrich Reinhold Lisiewsky, Barbara (Anna) Rosina de Gasc, and Anna Dorothea. Both Christian Friedrich Reinhold and Barbara Rosina held positions at German-speaking courts as portraitists.

Barbara Rosina’s first husband David Matthieu was a portrait painter with whom she had two children, Leopold Matthieu (a portrait painter) and Rosina Christiane Matthieu (a genre painter). It was within this family network that Therbusch’s artistic education began and flourished.

The Artist’s Professional Career

Unlike the majority of known eighteenth-century female painters, Therbusch began her professional career at the age of forty, after raising her children. In the twenty-one years from that point in time until her death, she completed an extensive oeuvre of 200 paintings, of which a majority are now lost.

Her re-engagement with painting began during the flowering of the arts under Friedrich II, called the Great. In 1740, he ascended the Prussian throne, and immediately began transforming the cultural landscape of Berlin. It was under the young king’s influence, and under the tutelage of painter Antione Pesne, a Frenchman who immigrated to Prussia, that German painters studied the French Rococo style. Although Therbusch was not listed as one of Pesne’s forty-five students (all of them male), she was acquainted with the artist, whose painterly style she imitated and whose portraits she is known to have copied.

Like her siblings, Therbusch painted numerous portraits, including members of the German-speaking aristocracy and notable members of Enlightenment society.

Honors and Later Life

She gained acclaim, becoming one of few female painters who were granted membership in the Académie des Arts in Stuttgart, the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture in Paris, and the Akademie der bildenden Künste in Vienna—a feat that also distinguished her from most of her male artistic colleagues. In 1770, the artist returned to Berlin, the city of her birth. Later in life she shared a studio with her brother, and also collaborated with him on portraits of the Prussian royal family for Catherine the Great of Russia.

Beyond Portraits

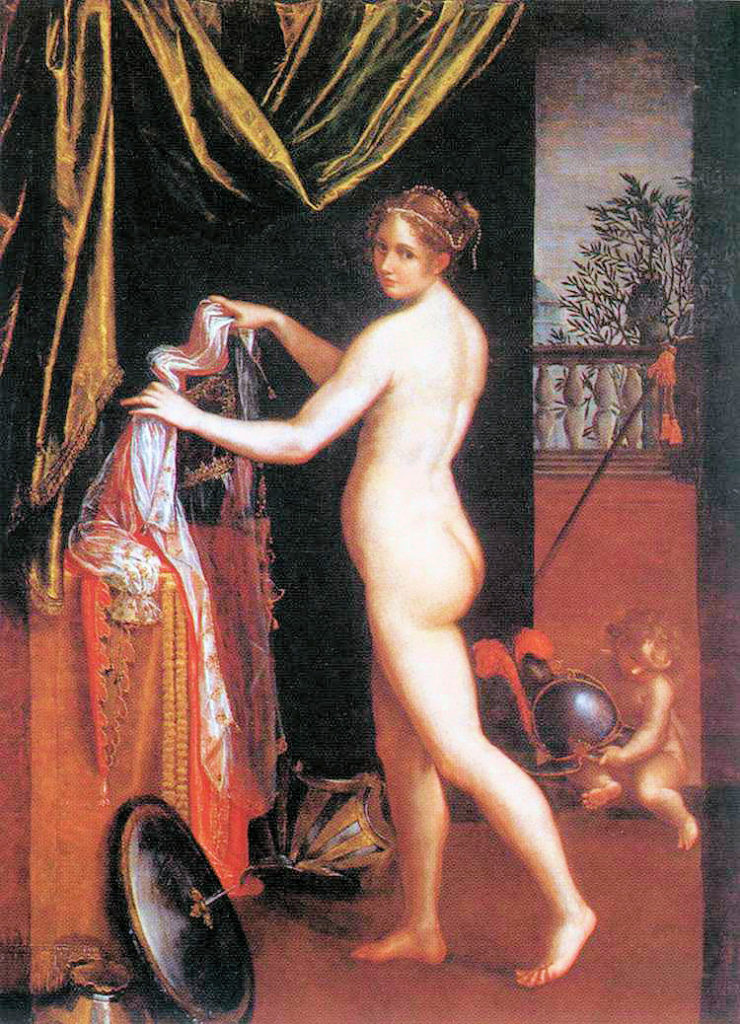

Throughout Therbusch’s professional career, she painted mythological and classical literary subjects for powerful men such Friedrich II; Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor; Duke Karl Eugen von Württemberg; and Karl Theodor von der Pfalz, Elector of Bavaria. Therbusch painted the nude and semi-nude figures of Venus, Ariadne, Syrinx, Cleopatra and Artemisia, as well as allegories of the arts, virtues, and four seasons.

Even after the Académie Royale rejected her painting Jupiter Transformed into Pan, Surprising the Sleeping Antiope, claiming that it was obscene, or when Denis Diderot published that the painting had “ignoble character” because she used “her chambermaid or her servant at the inn” as her model, she continued creating mythological paintings for the court in Prussia.

In 1772, she completed Diana with her Nymphs, commissioned by Friedrich II who paid a large sum of 600 Reichsthaler—the equivalent is a one year’s salary for a professor at the University of Leipzig. The painting is a wonderful representation of her mythological works and her study of the female nude. Therbusch followed a path set by Lavinia Fontana a century before, who was the first woman painter to break into the genre of mythology and the portrayal of the female nude.

When lexicographer and historian Johann Georg Meusel (1743–1820) noted in the journal Miscellaneen artistischen Innhalts that “it may be said that the training of her talent was like a Correggio,” the comparison in all likelihood referred to Therbusch’s paintings of erotic subjects from classical literature such as Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

A Final Accolade

In 1782, the year of her death, poet Johann Wilhelm Ludwig Gleim exclaimed that he wanted her portrait for his Temple of Friendship, to hang among the writers and intellectuals of his age. He added that he would have sold the work of Horace to commission a painting by Anna Dorothea Therbusch. One can assume that it is one of her mythological works for which he would have exchanged the work of the Roman author who penned the Ars Poetica.

Dr. Christina K. Lindeman specializes in the art and material culture of eighteenth-century German-speaking Europe. Her research was supported by numerous grants including a Stipendium Stiftung Weimarer Klassik und Kunstsammlungen, Samuel H. Kress Foundation Travel Fellowship, Francis Haskell Memorial Fund, and the Mahan-Brandon Research Fund for Research in Gender Studies and Women’s History. Her book Representing Duchess Anna Amalia’s Bildung: A Visual Metamorphosis from Personal to Political in Eighteenth-Century Germany was published with Routledge May 2017. She has presented several conference papers on Anna Dorothea Therbusch based on research trips to various archives, libraries and museums throughout Germany. Christina is currently working on a critical monograph of the artist’s work.

Berlin’s Gemäldegalerie pays tribute to the artist with the exhibition Anna Dorothea Therbusch: A Berlin Woman Artist of the Age of Enlightenment, which runs from December 3, 2021 to April 10, 2022.

More Art Herstory posts about 18th-century women artists:

Exhibiting Women: The Art of Professionalism in London and Paris, 1760–1830, by Paris Spies-Gans

Mary Linwood’s Balancing Act, by Heidi A. Strobel

Anna Dorothea Therbusch: A Woman Painting Against Eighteenth-century Odds, by Stephanie Pearson

Marie-Thérèse Reboul Vien: Finding the Natural in the Neoclassical, by Tori Champion

Adélaïde Labille-Guiard: Artist, Friend, Teacher, by Dr. Jessica L. Fripp

Rosalba Carriera at The Frick Collection, by Dr. Xavier F. Salomon

Seductive Surfaces: Anne Vallayer-Coster’s Vase of Flowers and Conch Shell at the Met, by Dr. Kelsey Brosnan

Marie-Guillemine Benoist, Revolutionary Painter, by Dr. Paris Spies-Gans

Angelica Kauffmann: Grace and Strength, by Dr. Anita V. Sganzerla

Angelica Kauffman and Mary Moser: Founding Women Artists of the Royal Academy

“I feel again the violence of a curious desire”: Rare client testimonies on Rosalba Carriera’s erotic art, by Dr. Angela Oberer

Rediscovering the Once Visible: Eighteenth-Century Florentine Artist Violante Ferroni, by Dr. Ann Golob

It’s exciting to see this overview–women artists at German courts are important but neglected–and I’m looking forward to the book!