Guest post by Laura Gowing, Professor of Early Modern History, King’s College London

The exhibition Bright Souls: The Forgotten Story of Britain’s First Female Artists, just opened in London’s Connaught Street. The show puts together for the first time the works of three seventeenth-century English women painters: the best-known, Mary Beale; her predecessor, Joan Carlile; and the youngest, Anne Killigrew.

Portrait of an Unknown Lady, 1650–5, by Joan Carlile (c. 1606–79). Held at the Tate,

It’s an extraordinary sight, a reminder of how Carlile or Beale’s studio might have looked, with their works clustered together. Beale was renowned for her portraits of children and her still lives. Carlile painted women over and over in white silk gowns—some look like the same dress. All of them painted women more than men. Carlile and Beale made a living from their work, maintaining their families and moving around Soho, Richmond and Suffolk to make their careers. Many of their works do not survive, or have been misattributed. One of the pleasures of this exhibition is to note the additions of modest drapery or false attributions that have accrued to the paintings over the centuries.

To us, it is perhaps the self-portraits that are most arresting, casting a new light on the autobiographical writings and letters that survive from elite women in the seventeenth century. To depict a self that was so often constructed as ‘but half a person’ could be challenging. Here is Beale, her brushes and painting tools in hand, seemingly caught in the act of self-representation; Carlile, on a family outing in Richmond Park; Killigrew, Killigrew, reflective in a loose red gown and no stays.

Bendor Grosvenor’s invaluable and deeply-researched exhibition catalogue fills in some of the many gaps in our knowledge, piecing together the lives and connections of these startlingly well-established painters. References to contemporary sale catalogues, to letters describing their work and lives, and to Beale’s own text about platonic friendship, lead us back into the world they inhabited. Mary Beale’s career was well-chronicled by her husband, who described her working practices. He gave details of the female studio apprentices who mixed her paints, one of whom went on to paint herself. For Killigrew, an amateur rather than a professional, painting went hand in hand with virtuoso writing. It was also a practical craft that required substantial investment in raw materials, tools, and space, and that helped constitute networks of patronage.

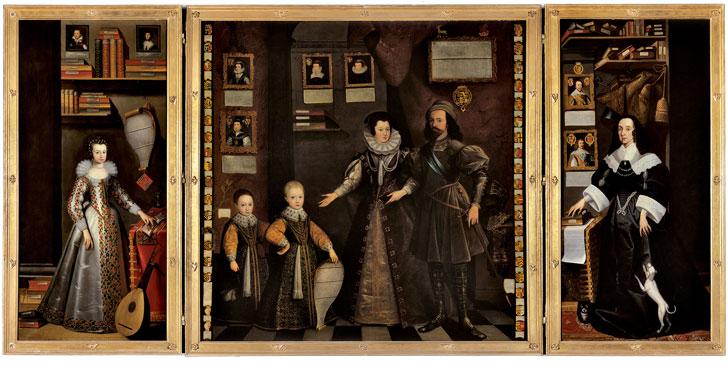

The catalogue and display cast female artistic achievement as something of a shock, in an era in which women were ‘peculiarly unfortunate’ to be born: believed by many to have no souls, deprived of all rights in common law, their marriages largely arranged, the merest eccentricities putting them at risk of witchcraft accusations. Beale, Carlile, and Killigrew stand out as exceptional. Yet they do not seem to have been so at the time, and part of the reason is the complex nature of women’s status in the seventeenth century. Women’s capacity to negotiate their place in law and in marriage was, we know from legal and personal records, considerable; arranged marriages were not common even amongst the elite. At home and in public the rhetoric of confinement and silence was challenged by assertion, autonomy and economic capacity. Anne Clifford commissioned her own portrait surrounded by her family, her favourite books, her tutors, and the evidence she had mustered of her property rights.

“This monumental painting presents the family history and accomplishments

of Lady Anne Clifford using a combination of portraiture, text and symbolism.”

Abbot Hall Art Gallery; source, ArtUK.

The ‘Bright Souls’ were, like many other early modern middling women, artisans working in a world where independent women’s work was common. Where and how they learned their trade is often obscure. Beale was apparently taught by her father and supported by her husband. Carlile was observed by a contemporary teaching at least one woman to paint, perhaps Killigrew. In the Painter-Stainers’ Company, a few women ran painters’ workshops, often working on household and coach painting, and took their own (male) apprentices. Rebecca Blackmore and her daughter-in-law petitioned in 1667 to complain they had not been paid for painting heraldic arms in the Royal Wardrobe. There was some overlap with the most common trade for women in seventeenth-century London, learning to sew: Daniel Savile, portraitist of Pepys, and his wife Dorothy took a series of girls as apprentices, working with Dorothy in her Royal Exchange stall. The market for appearance in late seventeenth-century London was sustained by quotidian female labour.

Bright Souls: The Forgotten Story of Britain’s First Female Artists is presented by Lyon & Turnbull. The exhibition is on at 22 Connaught Street, London, W2 2AF, June 24 to July 6, 2019. It is open to all, at no charge.

Dr. Laura Gowing is Professor of Early Modern History at King’s College, London. Her works on early modern women’s history include Domestic Dangers: Women, Words, and Sex in Early Modern London; Common Bodies: Women, Touch and Power in Seventeenth-Century England; and Gender Relations in Early Modern England. She is currently working on a book about women and apprenticeship in seventeenth-century London.

Work cited

Helen Draper, ‘Mary Beale and Art’s Lost Laborers: Women Painter Stainers’, Early Modern Women: An Interdisciplinary Journal10: 1 (2015)

More Art Herstory museum exhibition reviews:

A Room of Their Own: Now You See Us Exhibition at Tate Britain, by Kathryn Waters

Women Artists of the Dutch Golden Age at the National Museum of Women in the Arts

A Tale of Two Women Painters (Guest post by Natasha Moura)

Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists (guest post by Dr. Elizabeth Sutton)

More Art Herstory blog posts:

Susannah Penelope Rosse: Painting for Pleasure in Seventeenth-Century England, by Anna Pratley

Mary Beale (1633–1699) and the Hubris of Transcription, by Dr. Helen Draper

The Protofeminist Insects of Giovanna Garzoni and Maria Sibylla Merian (Guest post by Prof. Emma Steinkraus)

An Interview with Carrie Callaghan, Author of “A Light of Her Own”

The Priceless Legacy of Artemisia Gentileschi: A Curator’s Perspective (Guest post by Dr. Judith W. Mann)

New Adventures in Teaching Art Herstory (Guest post by Dr. Julia Dabbs)

Renaissance Women Painting Themselves (Guest Post by Dr. Katherine A. McIver)

Rachel Ruysch (1664–1750): A Birthday Post

An Interview with Joy McCullough, Author of “Blood Water Paint”

A Dozen Great Women Artists, Renaissance and Baroque

Why Do Old Mistresses Matter Today? (Guest Post by Dr. Merry Wiesner-Hanks)

Hello

How I wish I had seen this exhibition!

Is there a catalogue available for purchase?

I am writing a novel featuring 17th century artists in cameo roles;

Mary Beale in particular.

As I live in Adelaide, South Australia, it is difficult to access expert material.

Many thanks, Rae Hope

There is a catalogue, which you can view here, https://issuu.com/lyonandturnbullauctioneers/docs/bright_souls_britains_first_female_. I bought a print version a few months ago, which the Lyon & Turnbull staff kindly mailed to me. Perhaps they still have some for sale (for me, the cost with shipping was 10 pounds).

What a wonderful newsletter. This one is packed with so much information. Thanks for keeping it going! It’s much appreciated.