Guest post by Adelina Modesti, Honorary Senior Fellow, University of Melbourne

Introduction: a life devoted to art

A significant and influential artist of the Bolognese School of painting, Elisabetta Sirani (fig. 1) was born on Friday 8 January 1638 in Bologna in Northern Italy, the most important city of the Papal States after Rome. She was one of the most learned, innovative and successful artists of the period. She gained many public and private commissions, as well as critical acclaim and respect in a male-dominated profession. Extremely popular, she quickly became one of the most requested and collected Bolognese artists in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, with the value of her work above the norm.

The eldest of five children, Elisabetta was the daughter of the established Bolognese artist and art merchant, Giovanni Andrea Sirani (1610–1670) and Margherita Masini della Mano. Sirani, one of the best art professors and appraisers in the city, trained Elisabetta in painting, drawing, and printmaking, with a solid grounding also in art theory. Giovanni Andrea himself had been apprenticed to Guido Reni (1575–1642), the most important painter of Italy at the time, and he was Reni’s closest collaborator.

Giovanni Andrea, who ran a successful painting and printmaking studio, initially taught Elisabetta in Reni’s idealizing classical style, before she developed her own personal expressive and dynamic manner, considered by her contemporaries as “like a grand master” (Malvasia). At the same time her works, especially the Madonnas and Child, are intimate expressions full of human emotions played out in affectionate gestures and warm gazes (fig. 2). Elisabetta’s mentor and biographer Count Carlo Cesare Malvasia, who was a close family friend, stated that her many and varied Madonnas were the “most beautiful to be seen since those of the great Guido.”

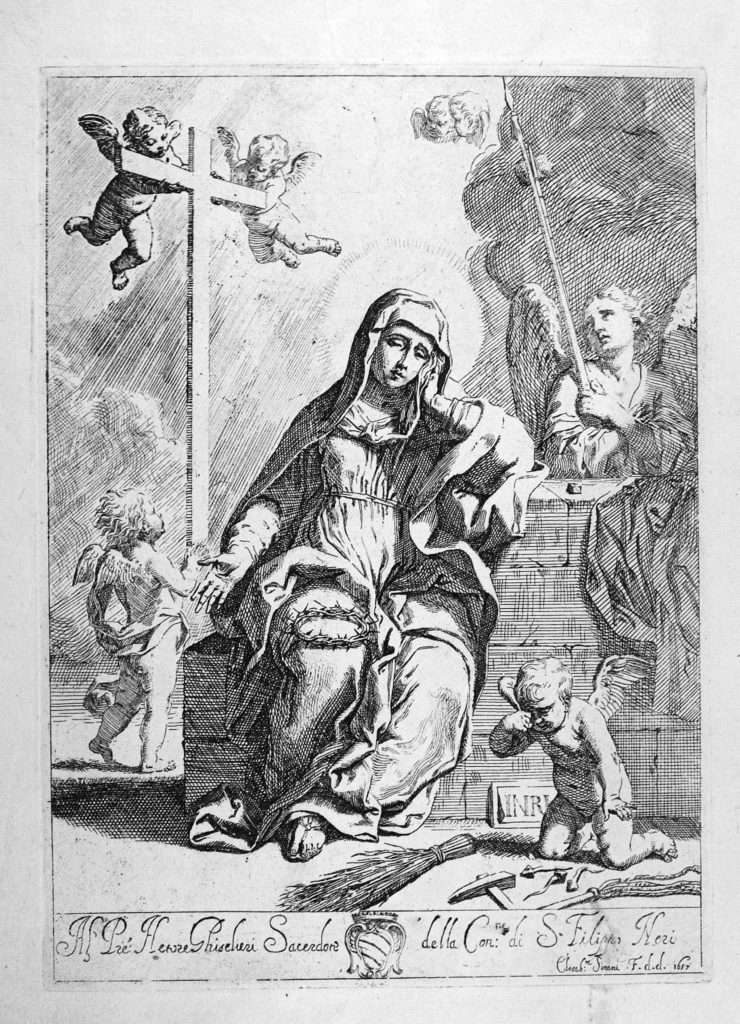

Elisabetta was also one of the first women to practice printmaking (see fig.12, below). By 1654, she was already an independent professional peintre-graveur. She became master of the Sirani workshop in her mid twenties, after her father had to stop painting due to arthritic gout that distorted his hands. She took on his apprentices, at the same time teaching in her female art school, supporting her extended family with the economic proceeds of her work. As her patron-agent Marchese Ferdinando Cospi noted, Elisabetta “is considered here [Bologna] a maestra, and it is she who maintains her large family with her work” (letter to Prince Leopoldo de’ Medici, 19 August 1662).

Elisabetta’s paintings in the main were paid for in kind—that is, in the form of expensive jewelry or gold, which was proudly displayed in a glass case in the Sirani reception room, contributing “to the common benefit of the household” (Malvasia).

Context

Elisabetta Sirani practiced her art right in the middle of the seventeenth century—the High Baroque, with its theatrical style and rhetorical visual language. Historically, it was the period of the Counter-Reformation, when the Catholic Church employed many artists in its theological and pastoral mission to bring the people back to the “true” faith. Artists could count on continual work from not only the Church, but also from private patrons who sought devotional pictures for their homes. Elisabetta was renowned for her sacred quadretti da letto (cabinet pictures) depicting the Madonna (fig. 2), Holy Family (fig. 3), or the Saints and Doctors of the Church such as John the Baptist, Mary Magdalen (fig. 4) and Jerome, in front of which her patrons could pray.

It was also a period when women did not have many opportunities to pursue a profession or career. They were usually denied an education or training, and so a young woman’s only options were to marry or enter a convent. Elisabetta was fortunate, however, in that she lived in a very progressive city with a liberal attitude towards female education and creativity. Bologna was renowned for its humanist tradition of learned women who taught and published. It was also the center of the largest school of female artists in Italy, mostly active between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries. Having an artist-father also helped Elisabetta establish herself as a successful painter and printmaker in a male-dominated profession. Most women at this time who pursued a professional career in the arts had a male relative who taught them in the family workshop.

Elisabetta then developed a matrilineal pedagogic model whereby girls were taught to draw and paint by a woman, rather than by their husbands, brothers, or fathers (as she had been). She opened her studio to female students, which included her two younger sisters Barbara and Anna Maria; the noblewoman Ginevra Cantofoli; and perhaps also Lucrezia Scarfaglia. Elisabetta was thus influential as a pioneering role model for subsequent generations of Bolognese women artists. As Malvasia wrote in 1678, there “have been, and still are numerous women and young girls who follow the example of this most worthy painter,” mentioning 11 in total. Whether daughters of artists or nobility, all of these women worked as professional artists—not only in Bologna but throughout Italy.

Moreover, Elisabetta never married nor had children, so was able to pursue her passion for art without the encumbrance of family responsibilities that befell most women. Elisabetta thus was a single professional woman, a newly emerging social category outside that of mother, wife, or nun, the usual roles assigned to women during this period.

Professional life

Elisabetta was recorded in the later seventeenth century as a member (“pittrice accademica”) of the painters’ Academy of St Luke, Rome, an indication of her professional standing and acceptance by the male art establishment. However, while women had been accepted as academicians since 1607, unlike their male counterparts they were not permitted to attend the meetings and theoretical classes. Hence there was still an uneven playing field when it came to access to academic training, especially drawing from the nude, which women could not do for reasons of propriety and decorum.

Notwithstanding these obstacles, in a career that barely spanned more than a decade (1654–65), Elisabetta went on to complete circa 200 canvases, of which 130 are extant; 15 prints; and innumerable drawings and wash sketches. Averaging about twenty canvases a year, this was a remarkable number for any artist. Thus not only was Elisabetta extremely productive, she demonstrated an extraordinary speed of execution. She was renowned for being able to finish a portrait bust in one sitting.

Elisabetta was much admired for this technical bravura and artistic virtuosity. The Florentine painter Baldassare Franceschini (Il Volterrano) who observed Elisabetta at work in 1662 claimed that she was “the best brush now in Bologna.” Her elegant canvases reveal an expressive and broad brushwork, fluid impasto, rich colouring and deep shadows. Contemporaries gendered Elisabetta’s painterly style as “masculine”: Malvasia claimed that her manner was “virile and grand,” while Padre Bonaventura Bisi wrote that she “painted like a man with much boldness and invention” (in a 1658 letter to Prince Leopoldo de’ Medici). Elisabetta was thus one of the first women artists to be publicly acknowledged by colleagues and critics as a female “virtuoso,” possessing artistic genius and invention, which usually was considered beyond women’s capabilities.

Subject matter

Elisabetta’s favourite subjects were women—whether sacred (figs. 2 & 4) or secular, mythological or allegorical. Her history painting celebrated their strength, dignity, intelligence, and courage, especially when pitted against male aggression. These femmes fortes,who Elisabetta depicted as independent historical agents, included the biblical Hebrew heroine Judith who slayed the enemy Holofernes (fig. 5); and classical ones like Timoclea who pushed her rapist down a well and stoned him to death (fig. 6), and Portia, the wife of Brutus (fig. 7). In this, her work bears comparison with Artemisia Gentileschi’s images of powerful, active women. The artist also painted the anti-heroines Delilah, Cleopatra, Circe (fig. 8) and Iole, highlighting their virtues rather than their vices.

An extremely erudite artist, Elisabetta learnt about these courageous historical women and prepared for her canvases by studying the ancient texts and handbooks in her father’s library, including the Old Testament, Plutarch’s Lives, and Ripa’s Iconologia. Church altarpieces (fig. 9), mythological allegories (fig. 10), and scenes from classical literature also feature in her repertoire, as do society and funerary portraits (fig. 11).

Patronage

Elisabetta’s many patrons included doctors, lawyers, priests and cardinals, scholars, noblewomen who wanted their portraits painted, senators, bankers, merchants, and artists. They came from all levels of Bolognese society: artisan, commercial, professional and intellectual circles, as well as the aristocratic, ecclesiastical and political elite. By the time Elisabetta reached her artistic maturity between 1662–64, she had become one of the most important and sought-after cultural figures in Bologna. The artist also boasted an international reputation. She was courted by royalty and by diplomatic leaders throughout Italy and Europe, such as the Medici, the Duchess of Bavaria and the King of Poland, who were eager to own a painting by her talented hand. Thus even within her own short lifetime, her work was represented in major European collections.

We know of her many patrons and the range and breadth of her artistic production through the multiple entries in her work diary, Note of the paintings made by me Elisabetta Sirani (1655–1665), later published by Malvasia in his Felsina Pittrice (Lives of the Bolognese painters) of 1678. Elisabetta here carefully documented each of her commissions, describing its subject matter and her often novel conceptualisation and interpretation, and identifying the 110 clients for whom her work was made.

Self-fashioning and Marketing

Elisabetta’s extensive patronage networks were developed through her own clever self-fashioning, display, and marketing strategies. One such strategy was to invite clients to watch her working in her studio. Another was the prominent use of her signature to fashion her own identity, independent from both Reni and her father, and to promote herself as a professional woman artist. She diplomatically gifted her paintings, drawings and prints (fig. 12) to patrons in order to cultivate future commissions.

Elisabetta also displayed her paintings and prints in temporary exhibitions, accompanied by published sonnets praising them and their creator. She sometimes used her own portrait in her images of heroic women (figs. 5 & 8), appealing to collectors who wished to own female artists’ self-portraits. Her father’s entrepreneurial management assisted Elisabetta in this, as did influential patrons and agents from Bologna’s aristocracy, like Malvasia, Cospi and Count Annibale Ranuzzi, who all enthusiastically promoted the young artist. Collectively, these strategems ensured Elisabetta’s professional and social success in a university city that actively encouraged women’s involvement in public and religious life, and valued female creativity, education and their intellectual achievements.

Epilogue

Elisabetta Sirani died suddenly on 28 August 1665 aged only 27, from the onset of peritonitis after a ruptured peptic ulcer. The elders of Bologna gave their “Painter Heroine” a public civic funeral to which the grief-stricken citizens, especially the women, flocked. The artist was laid to rest in the Chapel of the Rosary in San Domenico, next to the tomb of Guido Reni, Bologna’s other cultural hero.

This blog post is drawn from my article, “Maestra Elisabetta Sirani ‘Virtuosa del Pennello,’” Imagines, 2 (2018, August), 84–96.

Dr. Adelina Modesti is an Honorary Senior Fellow at the School of Culture and Communication (Art History), University of Melbourne. She is a former Lecturer in Art History at Monash University (1984–2002), ARC Fellow at La Trobe University (2008–2011), and AEUIFAI Fellow at the European University Institute, Florence (2008). Adelina is a recipient of many awards, and has published widely on women artists and female patronage of the early modern period. Adelina is the author of Elisabetta Sirani, published in the series Illuminating Women Artists (Lund Humphries, 2023; co-published in North America by Getty Publications). Her other publications include Elisabetta Sirani “Virtuosa.” Women’s Cultural Production in Early Modern Bologna (Turnhout: Brepols, 2014), and Women’s Patronage and Gendered Cultural Networks in Early Modern Europe. Vittoria della Rovere, Grand Duchess of Tuscany (London & New York: Routledge, 2020). She acts as consultant for international art auction houses, museums and cultural institutions, and is an AWA Advocate in Florence for the Advancing Women Artists Foundation, as well as an affiliated researcher on the ACIS and IDEA digital humanities project, Textiles, Trade and Meaning in the Courts of Early Modern Italy during the time of Isabella d’Este. .

Art Herstory now offers an Elisabetta Sirani note card, which reproduces Signora Ortensia Leoni Cordini as Saint Dorothy, the Chazen Museum’s painting by the artist. For more information about the card, visit the Art Herstory Shop. Don’t neglect to visit the Art Herstory Elisabetta Sirani resource page!

More Art Herstory blog posts about Italian women artists:

Three Historic Women Artists Exhibitions: A Dispatch from Italy, by Alessandra Masu

Plautilla Nelli and the Restoration of her Altarpiece Madonna del Rosario. by Jane Adams

Roma Pittrice: Women Artists at Work in Rome Between the Sixteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, by Alessandra Masu

Maddalena Corvina’s Saint Catherine of Alexandria, by Kali Schliewenz

Elisabetta Sirani’s Studio Visits as Self-Preservation: Protecting an Artistic Career, by Victor Sande-Aneiros

Judith’s Challenge, from Lavinia Fontana to Artemisia Gentileschi, by Alessandra Masu

Stitching for Virtue: Lavinia Fontana, Elisabetta Sirani, and Textiles in Early Modern Bologna, by Patricia Rocco

Thoughts on By Her Hand, the Hartford Iteration, by Erika Gaffney

By Her Hand: Personal Thoughts and Reflections on an Exhibition, by Oliver Tostmann

Giovanna Garzoni’s Portrait of Zaga Christ (Ṣägga Krǝstos), by Alexandra Letvin

In defense of monographic exhibitions of female artists: The case of Fede Galizia, by Camille Nouhant

The Ladies of Art are in Milan, by Cecilia Gamberini

“Artemisia” at the National Gallery: A Review, by Sheila McTighe

Elisabetta Sirani: Self-Portraits, Guest post by Jacqueline Thalmann

Celebrating Bologna’s Women Artists, by Babette Bohn

Drawings by Bolognese Women Artists at Christ Church, Oxford, by Jacqueline Thalmann

Lavinia Fontana and Elisabetta Sirani at the Smith College Art Museum, by Danielle Carrabino

Artemisia Gentileschi: What Wasn’t in the London Exhibition and Why it Matters, by Jesse Locker

Suor Orsola Maddalena Caccia (1596–1676), Convent Artist, Guest post by Angela Ghirardi

“Artemisia” at the National Gallery: A Review, Guest post by Sheila McTighe

Lavinia Fontana: Italy’s First Female Professional Artist, Guest post by Elizabeth Lev

“I feel again the violence of a curious desire”: Rare client testimonies on Rosalba Carriera’s erotic art, Guest post by Angela Oberer

“La grandezza del universo” nell’arte di Giovanna Garzoni / “The grandeur of the universe” in the art of Giovanna Garzoni (Guest post/review by Sara Matthews-Grieco)

Sister Caterina Vigri (St. Catherine of Bologna) and “Drawing for Devotion”, Guest post by Kathleen G. Arthur

Plautilla Bricci (1616–1705): A Talented Woman Architect in Baroque Rome, Guest post by Consuelo Lollobrigida

Two of a Kind: Giovanna Garzoni and Artemisia Gentileschi, Guest post by Mary D. Garrard

Suor Orsola Maddalena Caccia (1596–1676), Convent Artist, Guest post by Angela Ghirardi

Warp and Weft: Women as Custodians of Jewish Heritage in Italy, Guest post by Anastazja Buttitta

Rediscovering the Once Visible: Eighteenth-Century Florentine Artist Violante Ferroni, Guest post by Ann Golob

The Protofeminist Insects of Giovanna Garzoni and Maria Sibylla Merian, Guest post by Emma Steinkraus

A Tale of Two Women Painters, Guest post / exhibition review by Natasha Moura

Renaissance Women Painting Themselves, Guest post by Katherine McIver

The Priceless Legacy of Artemisia Gentileschi: A Curator’s Perspective, Guest post by Judith W. Mann

Trackbacks/Pingbacks