Two Generations of Bolognese Women Artists in the Museum Collection

Guest post by Danielle Carrabino, Curator of Painting and Sculpture, Smith College Museum of Art

Between 2019 and 2020, the Smith College Museum of Art (SCMA) acquired works by two Bolognese artists, Lavinia Fontana (1552–1614) and Elisabetta Sirani (1638–1665). It may be surprising to learn that Smith College, established in 1871 as one of the first colleges for women, does not have more art by women. This is a problem shared by most museums.

There are several reasons for this oversight. The collection at Smith, like so many others, is the result of gifts and purchases of mostly modern and contemporary American and European art. Consequently, there is a rather small number of historic works of art, and even fewer by women. As the years passed, it became increasingly more difficult to acquire pre-modern art. Additionally, the persistent preference for male artists and the misconception that there are no important works by women artists, even at a place like Smith College, has left a rather large hole in the collection. My fellow curators and I at the SCMA are among the many curators at museums in the US—and around the world—trying to rectify these oversights and misconceptions. My area of specialization in Renaissance and Baroque art (c. 1400–1700) led me to begin this process by adding these two remarkable artists to the collection.

Lavinia Fontana

Upon seeing the two miniature paintings by Lavinia Fontana, I was intrigued.

These are not traditional easel paintings, but are small in scale and fit together to form a kind of locket. Part material culture, part works of art, these miniatures are ideally suited to the SCMA’s teaching mission. The two small portraits of a man and a woman are portable and intimate. They portray an unidentified couple that is either engaged or soon to be married. Marriage marked an important milestone in the life of Renaissance women. At the time, a union could be based on love but it was more often a business transaction between two families. For an audience of primarily female students, it is valuable to learn about the lives of women in the past and understand the norms of their time. It was also important to purchase a work of art by a named woman artist who was celebrated during her own time but who male artists eventually overshadowed.

Lavinia Fontana was born in Bologna, a city that produced a remarkably large number of women artists. Fontana was the daughter of a painter, Prospero Fontana (1512–1597), who was her first teacher. It was common for women born to artistic families to be taught by their male relatives. This offered them the training otherwise unavailable to women, who were not typically admitted to art academies at the time. A main component of artistic training included working from the live male nude, deemed inappropriate for women.

Unlike many of her peers, Fontana studied art at the University of Bologna, where she earned a degree. She began her career as one of the most sought-after portraitists of the Bolognese elite.

She eventually took over the family workshop from her father, employing her husband as manager. Fontana’s art fetched high prices, enabling her to support her husband and eleven children entirely from her own income.

In 1604, she received the ultimate honor of painting at the court of Pope Urban VIII. Fontana is often considered to be the first woman artist in Renaissance Italy to be working on par with male artists of her day.

The double portrait of the man and woman is part of a larger group of round miniatures by Fontana. The woman wears red, the traditional color for Bolognese brides, and she is bedecked in jewelry. Fontana’s significantly larger portrait of a bride in the National Museum of Women in the Arts displays the costume and accoutrements of the Bolognese bride in greater detail.

The miniature portrait of the man, almost a mirror image of the woman, wears complimentary colors. The slightly larger dimensions of the male portrait, along with the raised decoration on the back of the panel, suggest that the two images originally would have fit together to form a locket or “portrait capsule,” symbolizing their union.

Little is known about the patronage of such portraits or how they were worn or carried. Though small in scale, the two miniature portraits are exquisitely detailed and possess a life-like presence.

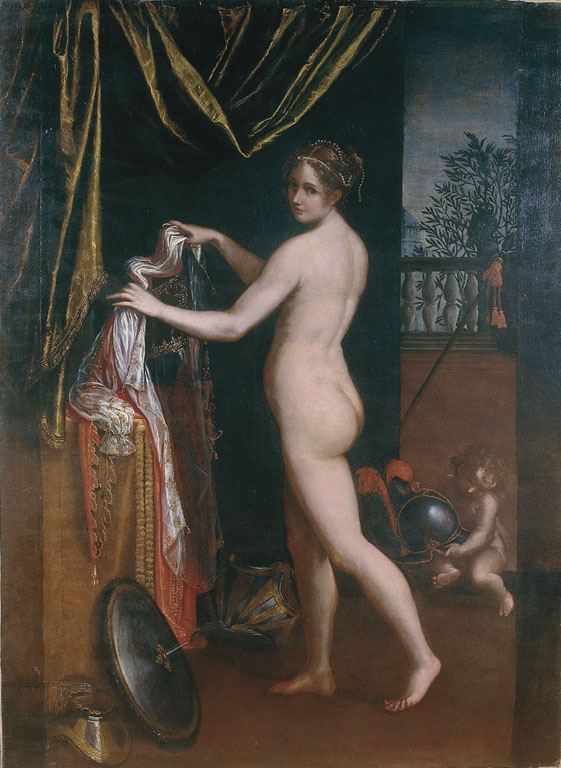

Elisabetta Sirani

A member of our Museum Visiting Committee first brought the drawing by Elisabetta Sirani to my attention.

It was soon to be sold at auction and he inquired whether it may be of interest. Although I am not the curator responsible for the vast collection of the SCMA’s works on paper, I often work closely with my curator colleagues to help acquire prints and drawings of historic art. Before I knew it, I had booked a trip to New York City to view the drawing in person.

Like Fontana, Sirani was born in Bologna to an artistic family. Her father, Giovanni Andrea Sirani (1610–70) was her first teacher. By the time she was seventeen, Sirani was already working as a professional artist. Tragically, she died suddenly only a decade later at the age of twenty-seven. Despite her short career, Sirani was extremely prolific. Despite the fact that she signed her work, she was accused of not being capable of producing so many paintings in so little time. To set the record straight, she invited people to visit her studio to witness the speed with which she painted.

Sirani made a name for herself in her native Bologna painting portraits, larger narrative scenes and public altarpieces, and smaller religious paintings for private use.

She was also skilled in drawing and printmaking. In addition to her many artistic accomplishments, Sirani was a teacher and founded an art academy that admitted both men and women. Her school was among the first in Europe to train aspiring women artists. A biographic account of Sirani by Carlo Cesare Malvasia stated that she was “the glory of the female sex, the gem of Italy, the sun of Europe.”

The drawn self-portrait by Sirani was probably created around 1658, when the artist was about twenty years old. The drawing does not appear to be related to any of Sirani’s painted self-portraits but does bear some resemblance to them.

Its small scale and the direct expression on Sirani’s face render it more immediate and less formal than her paintings. This drawing was probably not intended for the art market. As such, the self-portrait may have been deeply personal. The artist conveys a sense of self-assuredness that provides an intimate view into her character. Subtle details such as the curls framing her face, the lace in her dress, and the flush in her cheeks display her skillful draftsmanship.

This drawing appealed to me not only because it is by an exceptional woman artist, but also because it is a self-portrait. The artist portrayed herself at the same age as many Smith students. Of the many self-portraits in SCMA’s collection, few are by women. This genre provides insight into how the artist wishes the world to see her. In addition to providing the opportunity to compare this self-portrait to those by male artists in the SCMA collection, it also allows us to consider Sirani alongside Fontana.

Fontana and Sirani at Smith

The Fontana paintings and self-portrait by Sirani hold the distinction of being the earliest works of art by named women to enter the SCMA collection. The two paintings by Fontana are on display in the second-floor permanent galleries and the drawing is available by request through the Cunningham Center, also on the second floor.

Together, these two acquisitions begin to tell the story of two generations of women artists working in the same artistic center. (For more on the topic of women artists in Bologna, see Babette Bohn, Women Artists: Their Patrons, and their Publics in Early Modern Bologna.) They help to dispel the myth that there were no women artists before the modern era. They also debunk the idea that women in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Italy were beholden to their fathers and husbands, and reaffirm that women could forge a profession for themselves. Especially for Smith students, these are two very important lessons.

While it may be difficult to find historic works by women to add to the collection, it is not impossible. My colleagues and I do not exclusively collect art by women, but we are committed to adding works to the collection by artists who have been historically overlooked. Our overall aim is for a collection with a more equitable distribution of different types of artists. Personally, it is also important to me to spark interest in historic works of art. Smith students often take note when they learn about women, past or present, who have broken the mold or worked against societal expectations. As such, these two artists are decidedly modern. Indeed, Fontana and Sirani are not unlike Smith students in their aim for excellence and sense of ambition.

Dr. Danielle Carrabino was born in the US and spent her formative years attending middle and high school in Florence, Italy. She is an historian of Italian Renaissance and Baroque art and a curator at the Smith College Museum of Art (SCMA), where she oversees works from antiquity to 1950. She has worked at several museums, including the National Museum of Women in the Arts, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Harvard Art Museums. She also has an extensive record of teaching art history in the United States, England, and Italy at both the university and graduate levels. In 2018, she took up her position at the SCMA. Her projects there have included exhibitions, research, and teaching from the collection. She has acquired several works of art through gifts and purchases, several by women artists. She continues to conduct research, attend conferences, and publish in her field of interest.

More Art Herstory blog posts about Lavinia Fontana or Elisabetta Sirani:

Elisabetta Sirani’s Studio Visits as Self-Preservation: Protecting an Artistic Career, by Victor Sande-Aneiros

Stitching for Virtue: Lavinia Fontana, Elisabetta Sirani, and Textiles in Early Modern Bologna, by Dr. Patricia Rocco

The Restoration of Royalty: Lavinia Fontana’s Queen of Sheba and King Solomon, by Dr. Aoife Brady

Elisabetta Sirani: Self-Portraits, Guest post by Jacqueline Thalmann

Drawings by Bolognese Women Artists at Christ Church, Oxford, Guest post by Jacqueline Thalmann

Elisabetta Sirani of Bologna (1638–1665), Guest post by Dr. Adelina Modesti

Lavinia Fontana: Italy’s First Female Professional Artist, Guest post by Dr. Elizabeth Lev

Renaissance Women Painting Themselves, Guest post by Dr. Katherine McIver

Art Herstory Resource Page: Lavinia Fontana

Art Herstory Resource Page: Elisabetta Sirani

More Art Herstory blog posts about Italian women artists:

Maddalena Corvina’s Saint Catherine of Alexandria, by Kali Schliewenz

Judith’s Challenge, from Lavinia Fontana to Artemisia Gentileschi, by Alessandra Masu

Thoughts on By Her Hand, the Hartford Iteration, by Erika Gaffney

Plautilla Bricci: A Painter & “Architettrice” in Seventeenth-century Rome, by Alessandra Masu

By Her Hand: Personal Thoughts and Reflections on an Exhibition, by Oliver Tostmann

Sister Eufrasia Burlamacchi (Lucca, 1478–1548), by Dr. Loretta Vandi

Giovanna Garzoni’s Portrait of Zaga Christ (Ṣägga Krǝstos), by Dr. Alexandra Letvin

Celebrating Bologna’s Women Artists, Guest post by Dr. Babette Bohn

Artemisia Gentileschi: What Wasn’t in the London Exhibition and Why it Matters, Guest post by Dr. Jesse Locker

“La grandezza del universo” nell’arte di Giovanna Garzoni / “The grandeur of the universe” in the art of Giovanna Garzoni (Guest post/review by Dr. Sara Matthews-Grieco)

Plautilla Bricci (1616–1705): A Talented Woman Architect in Baroque Rome, Guest post by Dr. Consuelo Lollobrigida

Sister Caterina Vigri (St. Catherine of Bologna) and “Drawing for Devotion,” Guest post by Dr. Kathleen G. Arthur

Orsola Maddalena Caccia (1596–1676), Convent Artist, Guest post by Dr. Angela Ghirardi

“Artemisia” at the National Gallery: A Review, Guest post by Dr. Sheila McTighe

Two of a Kind: Giovanna Garzoni and Artemisia Gentileschi, Guest post by Dr. Mary D. Garrard

The Priceless Legacy of Artemisia Gentileschi: A Curator’s Perspective, Guest post by Dr. Judith W. Mann

Talking Artemisia Gentileschi with Joy McCullough, Author of “Blood Water Paint”

New from Art Herstory: The Artemisia Gentileschi Christmas Card

Art Herstory Resource Page: Artemisia Gentileschi

Art Herstory Resource Page: Giovanna Garzoni

Art Herstory Resource Page: Orsola Maddalena Caccia

Art Herstory Resource Page: Sofonisba Anguissola

Trackbacks/Pingbacks