Guest post by Catherine Powell, University of Texas at Austin & Leiden University Centre for the Arts in Society

Alida Withoos thrived as still life painter and botanical illustrator during the late seventeenth century in the Dutch Republic. As a member of a family of artists, Withoos developed her own style and had a successful career. She became part of a significant network of artists and botanical experts and amateurs. Although today we know little about her life, Alida Withoos contributed to some of the most important botanical artistic projects of her time.

Many Withoos, only one Alida

Alida Withoos was born between 1659 and 1661, the second daughter and fourth child of the painter Matthias Withoos (1627–1703). When Alida was still young, the French invaded the Dutch Republic, during the so-called Year of Disaster of 1672 (Rampjaar). To escape the French troops, the family relocated from Amersfoort to Hoorn. Alida married in Amsterdam in 1701 to the painter Andries Cornelisz. Van Dalen (1672–?). He may have been related to the van Dalen family of engravers, although we know little about him. Alida continued living in Hoorn until her father’s death, in 1703. She then moved to Amsterdam. She and her husband had no children. Withoos was buried on 5 December 1730.

A notable father

Matthias Withoos, Alida’s father, was a well-known and respected painter. He was born and worked in Amersfoort, where he was a member of the Guild of Saint Luke. He worked in Hoorn from 1672 until the time of his death in 1703. Matthias apprenticed with Jacob van Campen (1596–1657), who designed the new town hall in Amsterdam.

Matthias painted landscapes and still lifes of various types, including garden and hunting still lifes and still lifes with a forest floor (sottobosco). He was particularly appreciated for the level of detail he achieved on the insects and animals that occupied the forefront of his compositions.

In the steps of Matthias

Five of the eight Withoos children trained as painters. In addition to Alida, these included the Withoos siblings Pieter (1654–1692), Johannes (1656–1688), Maria (1663–after 1699), and Frans (1665–1705). All of the children specialized in still life and in the representation of nature, animals, and insects. Many of the still lifes they painted shared a common aesthetic and compositional affinities with those of Matthias. We can see these similarities, for example, in the three paintings below, by Frans, Alida, and Maria.

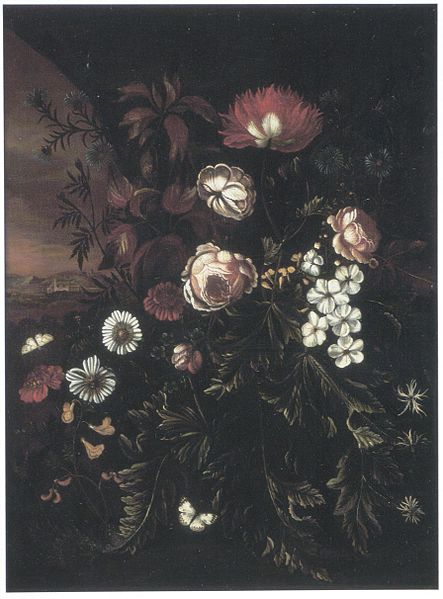

Figure 5. Alida Withoos, Flowers before an Italianate landscape, ca. 1690, oil on canvas, 110 x 94.5cm (43 5/16 x 37 3/16in). Private Collection. Image Bonhams.

Figure 6. Maria Withoos, Flowers before an Italianate landscape with evening sky, c. 1700, oil on canvas, 86.4 x 64.2 cm. Whereabouts unknown. Image RKD.

In each case, the artist has grouped flowers, almost as if in a bouquet. They are placed in the immediate foreground in front of a large tree. The dusk light bathes the landscape behind. In these aspects, the paintings clearly bear the heritage of Matthias’s style. Interestingly, Alida and Maria have situated their still lifes in an Italianate landscape, even though neither one of them traveled outside of the Dutch Republic. Matthias, however, spent time in Rome with the painters Otto Marseus van Schrieck (1619/20–1678) and Willem van Aelst (1627–1683). It is likely that the sisters were borrowing from the landscapes they had seen their father paint.

Imitating nature

Alida Withoos displayed enormous skill in illustrating highly detailed, life-like specimens of flowers and plants. Her illustrations were scientifically accurate and could be used for identification. They were also aesthetically pleasing and exceptional works of art in their own right. Study of a Hanekam, below, provides a representative example of her skills. In one shoot of the plant, Withoos has captured the different stages of growth and blooming, from budding to near-withering. This would have allowed botanists to identify the plant at various stages of growth. With micro-strokes of her brush and shading, she replicates the velvety texture of the flowers in a way that renders the drawing almost tactile.

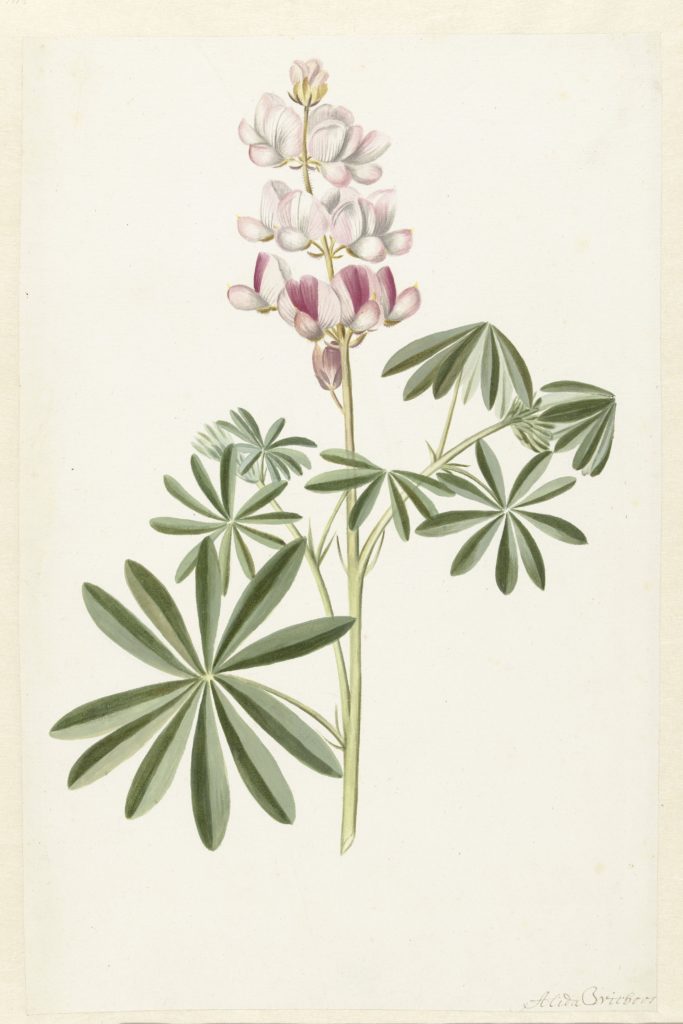

Similarly, the careful application and layering of color to this watercolor of a lupine conveys the delicy of its flowers. Withoos arranged the leaves of the plant along a diagonal and foreshortened the cluster of leaves in the bottom left to create the impression of depth.

Part of an important network

Alida was the most productive of the siblings. Not only did she paint in oil, but she also excelled at portraying plants and flowers in watercolor. She was in high demand amongst the best known botanical experts and amateurs (liefhebbers, in Dutch or Curieux, in French). One such amateur botanist was the patron and collector Agnes Block (1629–1704). Block owned and developed the country estate of Vijverhof, southwest of Amsterdam. There, she grew rare and exotic plants, even contributing several species to the public gardens of Amsterdam and Leiden.

Block was enormously wealthy and commissioned the best artists of her time to immortalize her garden. These artists included Otto Marseus van Schrieck, Maria Sibylla Merian (1647–1717) and her daughter Johanna Helena Herolt (1668–after 1723), Maria Moninckx (1676–1757), and Alida Withoos, amongst others. When Block succeeded in growing a pineapple in her hot house—the first person in the Dutch Republic to do so—it was to Alida she turned for a “portrait.” Although this illustration no longer survives, it might have looked like this pineapple from Surinam, illustrated by Maria Sibylla Merian.

Another liefhebber who retained the services of Alida Withoos was Simon Schijnvoet (1653–1727). Schijnvoet was an architect, a landscape architect, an engraver, a draftsman, a poet, a playwright, and a collector or art and naturalia. Alida contributed six drawings to his collection of watercolors, or Konstboek. (Her brother Pieter contributed one drawing.) Alida’s impact on the Konstboek, however, was much greater than her six drawings. The greatest contributor to Schijnvoet’s album was Catharina Lintheimer, who was a follower of Alida.

A monumental project

Alida participated in the creation of an atlas of the rare and exotic plants of the Amsterdam hortus, a massive undertaking which would take two decades and four hundred and twenty watercolors to complete. This atlas is now known as the Moninckx Atlas, in honor of the artist in charge of the project, Jan Moninckx. It was one of the most (if not the most) ambitious botanical artistic project of the time. Alida was one of four women to contribute to the atlas. The others were Maria Moninckx, Johanna Helena Herolt, and Dorothea Storm-Kreps (1734–1772).

Thus, in addition to being a gifted painter of still lifes, Alida Withoos belonged to a circle of highly talented and sought-after botanical artists. Collectors acquired her works, and experts turned to her when they needed high-end, scientifically accurate illustrations. Through that work, Alida contributed to the creation and dissemination of botanical knowledge, a contribution from which we still benefit.

Catherine Powell is a PhD candidate in art history at the University of Texas at Austin. She is currently a Kress Institutional Fellow at the Leiden University Centre for the Arts in Society. Her research focuses on the role of early modern women in the creation, production, and patronage of art in the Low Countries. Her dissertation concerns the patron, collector, and amateur botanist Agnes Block (1629–1704). In particular, Powell examines Block’s use of and reliance upon networks of artists and expert and amateur botanists in the establishment of her reputation as a knowledgeable botanist and her identity as Flora Batava.

Visit Art Herstory’s Alida Withoos resource page.

Other Art Herstory blog posts about Dutch or Flemish women artists:

Dutch and Flemish Women Artists—A Major Exhibition at the National Museum of Women in the Arts, by Erika Gaffney

A Year for Dutch and Flemish Women Artists

Rachel Ruysch: The Art of Nature, by Stephanie Dickey

Rachel Ruysch’s Vase of Flowers with an Ear of Corn, by Lizzie Marx

Women and the Art of Flower Painting, by Ariane van Suchtelen

Thérèse Schwartze (1851–1918), by Ien G.M. van der Pol

Anna Maria van Schurman: Brains, Arts and Feminist avant la lettre, by Maryse Dekker

Curiosity and the Caterpillar: Maria Sibylla Merian’s Artistic Entomology, by Kay Etheridge

Books, Blooms, Backer: The Life and Work of Catharina Backer, by Nina Reid

From a Project on Women Artists: The Calendar and the Cat Lady, by Lisa Kirch

Levina Teerlinc, Illuminator at the Tudor Court, by Louisa Woodville

Gesina ter Borch: Artist, not Amateur, by Nicole E. Cook

A Clara Peeters for the Mauritshuis, by Quentin Buvelot

Floral Still Life, 1726—A Masterpiece by Rachel Ruysch, by Lawrence W. Nichols

Women Artists of the Dutch Golden Age at the National Museum of Women in the Arts

The Protofeminist Insects of Giovanna Garzoni and Maria Sibylla Merian, by Prof. Emma Steinkraus

Susanna Horenbout, Courtier and Artist, by Dr. Kathleen E. Kennedy

More Art Herstory blog posts you might enjoy:

Historic Women Artists and Still Life at The Hyde Collection, by Erika Gaffney

Louise Moillon: A pioneering painter of still life, by Lesley Stevenson

Marie-Thérèse Reboul Vien: Finding the Natural in the Neoclassical, by Tori Champion

Barbara Regina Dietzsch: Enlightened Flower Painter, by Andaleeb Badiee Banta

Madeleine Françoise Basseporte’s Hyacinths at the French Court, by Mary Creed

Women in Zoological Art and Illustration, by Ann Sylph, Librarian of the Zoological Society of London

Orsola Maddalena Caccia (1596–1676), Convent Artist, by Dr. Angela Ghirardi

Two of a Kind: Giovanna Garzoni and Artemisia Gentileschi, by Dr. Mary D. Garrard

“La grandezza del universo” nell’arte di Giovanna Garzoni / “The grandeur of the universe” in the art of Giovanna Garzoni, by Dr. Sara Matthews-Grieco

I like Alida’s nature illustrations and would love to see them on cards, bookmarks, and magnets!

Thank you very much for the information. I have done some research on Alida. I am a bibliophile and collector in beaux-arts, mainly early modern European. I am the happy owner of a flower painting by Alida.

I doubt I’ll find in my research files (dates from a while ago) anything more about Alida following your wonderful presentation, but I will look and see if there is anything I can contribute.

Best, L.G. Paris

Thank you so much for the very interesting article on Alida Withoos! I am writing a book on Dutch paintresses in the 17th century, and make a point of including some of the lesser known women painters of that time, like Aleijda Wolfsen and Alida Withoos.

One tiny correction: the Dutch for ‘year of disaster’ is ‘Rampjaar’ (not: Raampjaar).

Thank you!