Guest post by Sara Matthews-Grieco, Syracuse University in Florence

This guest post reviews the recent art exhibition, curated by Dr. Sheila Barker, presented by the Uffizi Galleries at Andito degli Angiolini, Palazzo Pitti, Florence, Italy, 28 May–28 June 2020 (originally scheduled 10 March–24 May 2020).

This was a jewel of a show. “Was” because it could only be open for a month after it had been originally scheduled, due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Yet while it ran only a few weeks, and despite torrential rains and a dearth of tourists in Florence, it was exceedingly well attended, to the extent that social distancing had to be enforced in the suite of rooms that made up the exhibition space.

Giovanna Garzoni (Ascoli Piceno 1600–Rome 1670) has been the object of increasing interest on the part of art historians, gender historians, historians of botanical illustration, and scholars of court life in seventeenth-century Italy. The entire show was organized thematically; each room explored another aspect of Garzoni’s life and career, with an emphasis on her versatility as an artist. Garzoni worked extensively within Italy, moving (as did most artists and musicians) between Venice, Florence, Rome, Naples and Turin. She even went to England with Artemisia Gentileschi, and on her return spent some time at the court of Louis XIII, whence her miniature portrait of Cardinal Richelieu. Like many women artists of her time, she had received an elite education—letters, music and art—that facilitated her entry into the highest courts in Europe.

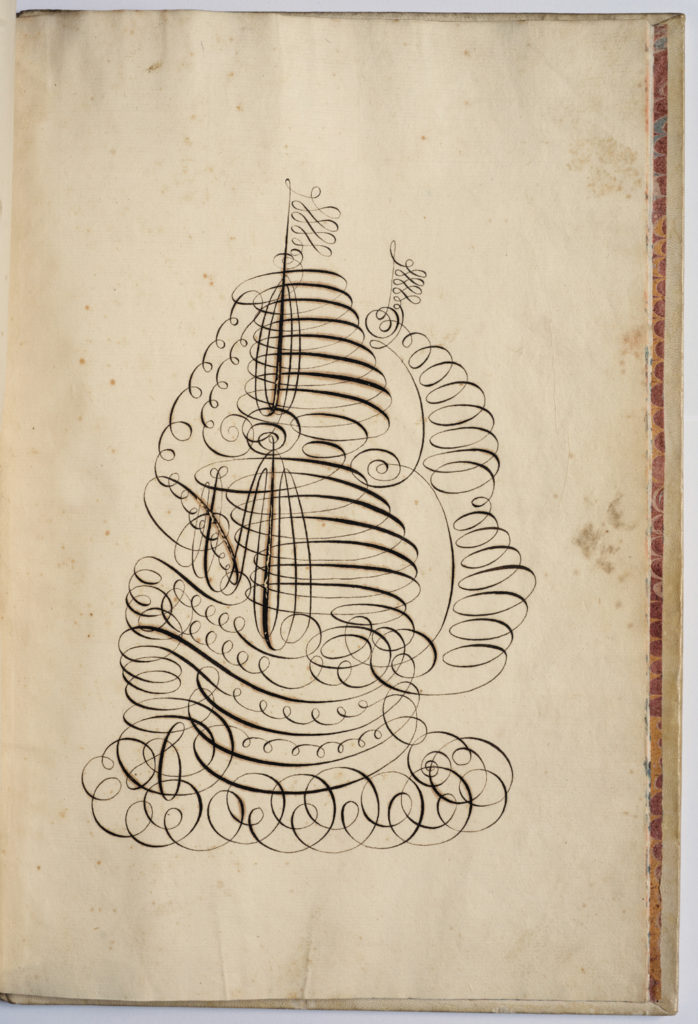

As a highly skilled female painter who excelled in calligraphy, portraiture, miniatures and botanical subjects (often with a touch of whimsy), she received the patronage of both aristocratic courts and powerful male artists, eventually becoming an honorary member of the prestigious Accademia di San Luca in Rome. Her brief marriage to a Venetian portrait artist, Tiberio Tinelli, was quickly annulled due to her vow of celibacy (attributed to a “prophecy” that she would die in childbirth) and purported magical practices on the part of Tinelli. Garzoni was never to remarry but would henceforth live and travel with her brother Mattio as a chaperone.

The first of the exhibition’s six rooms displayed some of her remarkable portraits, including a miniature of the self-proclaimed Prince, Saga Chrestos, a pretender to the throne of Ethiopia who converted to Christianity and toured the courts of Europe. Garzoni was in the service of the Duchess of Savoy at that time, and presumably painted this portrait in the winter of 1634–35, when Chrestos was given hospitality at the court of Turin in order to recover from an illness.

In sixteenth-century Italy, women artists (notably Sofonisba Anguissola and Lavinia Fontana) had created a new genre in portraiture: the self-portrait of the woman artist with a musical instrument. Such self-portraits were a visual tour de force that testified simultaneously to the skill of the painter as a portraitist, to her accomplishment as a musician, and to her unusual status as a female in a profession that was largely held by men. Thus the early self-portrait of Giovanna Garzoni, executed when she was between 18 and 20 years old, depicts her as a laurel-wreathed Muse or androgynous Apollo, holding a stringed viol. Female self-portraits were often given as gifts to aristocratic patrons of the arts in order to make a young artist known, and to stimulate curiosity about her work.

circa 1639, by Giovanna Garzoni. Rome, Accademia Nazionale di San Luca.

Like many artists of her time, Giovanna Garzoni copied drawings and paintings by other artists, but often added a little touch of originality in the subject’s gesture or expression. Thus Garzoni’s copy of a sheet of sketches of animals and landscapes by Albrecht Dürer—presumably in the collection of Inigo Jones and copied when Giovanna was in England—provides one of the signature details of the exhibition. A sleeping lioness depicted in the Dürer drawings was exactly copied by Garzoni, with small but amusing variants: Garzoni emphasizes the lioness’s one open eye, and deepens the lines of her mouth into a quasi-smile. Miniature copies of paintings by Raphael were commissioned by her Medici patrons, who even permitted her to borrow the large tondo of the Madonna della Seggiola (Madonna of the Chair) in order to copy it—and noted later that it was returned a bit damaged!

Contact with the new scientific academies in Rome, with Cassiano dal Pozzo, and Florence, with Jacopo Ligozzi, gave Garzoni exposure to the period enthusiasm for gardens and plants, and the widespread production of botanical images commissioned by enthusiasts. Giovanna produced her own, meticulously executed collection known as “Piante Varie,” but it would be the botanical still-life, with fruits and flowers and insects, that was to become one of her most successful subjects. Here too, Garzoni would presumably have seen the innovative still-lifes by Fede Galizia that belonged to the court of Savoy, but Garzoni created a much lighter, brighter genre. Her small, beautifully executed paintings of fruits, insects, and shells or exotic objects were especially appreciated by her Medici patrons, who continued to support her throughout her life.

The Medici passion for collecting flower varieties are at the root of some of Garzoni’s larger paintings of bouquets. A breath-taking tempera-on-parchment depiction of a bunch of exotic flowers arranged in a Yixing porcelain vase, flanked by two exotic shells and surmounted by butterflies, evokes the four elements (shells = water, ceramic vase = fire[d], flowers = earth, butterflies = air). At the same time, it makes a statement about the global reach of the Medici collections of “curiosities,” here ranging from Asian porcelain to the seashells of Central America. This kind of visual global statement was intended to intrigue the viewer and stimulate their imagination, triggered by the geographic compass of the Granducal collections.

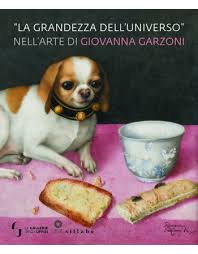

A delightful aspect of the exhibition is the juxtaposition of the objects depicted in the Garzoni still-lifes with the same (or practically identical) objects held in Florentine collections or other museums derived from the “curiosity cabinets” of early modern Italy (see picture of socially distanced visitor, above). A Wunderkammer was to be found in every European court, and Garzoni would have seen many in her travels. The exhibition thus displays real seashells from Central America, and porcelain plates and vases from China taken from the Medici and other historic collections, items that are similar or even identical to those which appear in Garzoni’s paintings along with more familiar fruits and vegetables. The charming portrait of a miniature English lapdog next to a Chinese cup (of the type used for drinking chocolate) a slice of bread and a (sweet?) biscuit with two lifelike flies also carries the viewer into an intimate world of aristocratic taste, while at the same time promoting an image of the “global” reach of the Medici household. The annoying flies on the biscuit add an amusing touch that is not unusual in Italian painting, and can be traced back to an anecdote about a fly painted by Giotto.

The lapdog was presumably a favorite of Vittoria della Rovere, Granduchess of Tuscany, whose personal “curiosity cabinet” has been partially reconstructed in the last room of the exhibition, thanks to an unpublished inventory. A special space was created in the Villa of Poggiolo Imperiale after Garzoni’s death to house her still-lifes and other paintings, small bronze and ivory sculptures, colourful porcelain from Asia, and exotic drinking goblets made of a nautilus shell, coconuts, and a special Mexican clay that cools liquids through evaporation.

The exhibition also put on display a little-known work by Garzoni that demonstrates her talent in textile arts, here put to service in a “paliotto” or front cover for an altar. Over 4 meters long, it features a varied floral motif with God the Creator at the center, and mixes flowers with religious connotations, such as the rose and the carnation, along with more exotic varieties that demonstrate the immensity of divine creation.

Sewn-together pieces of taffeta form the background for vibrantly coloured silk pasted on paper, cutout, glued and lightly painted in order to convey detail that could be seen at a distance. Commissioned as a gift for the church of Santa Maria Novella in Florence, this is the only known example of textile work by Garzoni, although records show that she was often engaged with such materials. The wonderful exhibition catalogue, edited by exhibition curator Sheila Barker, brings together a series of essays on different aspects of Garzoni’s life and career, and is dedicated to Jane Fortune, the late patroness of the arts and founder of the Advancing Women Artists organization in Florence.

Amongst the internationally recognized scholars Barker has united in this beautifully illustrated volume are three generations of female researchers whose work has put women artists (and their female patrons) prominently back into the narrative of European art history. Mary D. Garrard and Sheila ffolliott belong to a vanguard of American art historians whose work in the 1980s has remained pivotal for the study of women as artists in Renaissance and Baroque Europe. Sheila Barker herself belongs to the “next” generation of art historians who are focusing the spotlight on the lesser-known women artists whose work, in all media, has often been discounted as being “secondary” although they were highly regarded in their lifetime. The third and most recent generation of scholars working on women artists are talented graduate students, such as Dana Hogan, whose meticulous research is evidenced in many of the more developed commentaries on individual paintings.

Dr. Sara Matthews-Grieco is Professor of History & Women’s and Gender Studies, Syracuse University, Florence (1987–2017). Her work on Renaissance and early modern women and art ranges from the monograph Ange ou diablesse. La représentation de la femme au XVIe siècle, to editing/participating in collective volumes such as Picturing Women in Renaissance and Baroque Italy, and Erotic Cultures in Renaissance Italy. She is currently working on a book on Prints and the Codification of Visual Language in Europe (1450-1650).

The exhibition catalogue—”The Immensity of the universe” in the Art of Giovanna Garzoni, edited by Sheila Barker—is available for order through Casa Editrice Sillabe. Contributors include Aoife Cosgrove, Anatole Tchikine, Sheila ffolliott, Elena Fumagalli, Mary D. Garrard, Lucia Tongiorgi Tomasi, Francesco Morena, Peter M. Lukehart, and Pasquale Focarile.

**

As of November 2020, Art Herstory offers a Giovanna Garzoni note card! Visit the shop for details. See also the Art Herstory Giovanna Garzoni resource page.

More Art Herstory blog posts about Giovanna Garzoni:

Giovanna Garzoni’s Portrait of Zaga Christ (Ṣägga Krǝstos), by Dr. Alexandra Letvin

Two of a Kind: Giovanna Garzoni and Artemisia Gentileschi, by Dr. Mary D. Garrard

The Protofeminist Insects of Giovanna Garzoni and Maria Sibylla Merian, by Dr. Emma Steinkraus

More Art Herstory museum exhibition reviews:

Roma Pittrice: Women Artists at Work in Rome Between the Sixteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, by Alessandra Masu

Making Her Mark Leaves its Mark at the Art Gallery of Ontario, by Isabelle Hawkins

Early Modern European Women Artists at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, by Erika Gaffney

Sofonisba Anguissola in Holland, an Exhibition Review, by Erika Gaffney with Cara Verona Viglucci

Judith’s Challenge, from Lavinia Fontana to Artemisia Gentileschi, by Alessandra Masu

Anna Dorothea Therbusch: A Woman Painting Against Eighteenth-century Odds, by Stephanie Pearson

Thoughts on By Her Hand, the Hartford Iteration, by Erika Gaffney

Plautilla Bricci: A Painter & “Architettrice” in Seventeenth-century Rome, by Alessandra Masu

Thoughts on Feminist Art History in the Wake of Artemisia: Vrouw & Macht at Rijksmuseum Twenthe, by Dr. Jitske Jasperse

By Her Hand: Personal Thoughts and Reflections on an Exhibition, by Oliver Tostmann

In defense of monographic exhibitions of female artists: The case of Fede Galizia, by Camille Nouhant

The Ladies of Art are in Milan, by Cecilia Gamberini

A Tale of Two Women Painters, by Natasha Moura

Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists, by Dr. Elizabeth Sutton

‘Bright Souls’: A London Exhibition Celebrating Mary Beale, Joan Carlile, and Anne Killigrew, by Dr. Laura Gowing

More Art Herstory posts about Italian women artists:

The Restoration of Royalty: Lavinia Fontana’s Queen of Sheba and King Solomon, by Dr. Aoife Brady

Artemisia Gentileschi: What Wasn’t in the London Exhibition and Why it Matters, by Dr. Jesse Locker

“I feel again the violence of a curious desire”: Rare client testimonies on Rosalba Carriera’s erotic art, Guest post by Dr. Angela Oberer

Plautilla Bricci (1616–1705): A Talented Woman Architect in Baroque Rome, by Dr. Consuelo Lollobrigida

Sister Caterina Vigri (St. Catherine of Bologna) and “Drawing for Devotion,” by Dr. Kathleen G. Arthur

Orsola Maddalena Caccia (1596–1676), Convent Artist, by Dr. Angela Ghirardi

Rediscovering the Once Visible: Eighteenth-Century Florentine Artist Violante Ferroni, by Dr. Ann Golob

Renaissance Women Painting Themselves, by Dr. Katherine McIver

The Priceless Legacy of Artemisia Gentileschi: A Curator’s Perspective, by Dr. Judith W. Mann

Thanks for really bringing it to life for those of us who could not attend.

Having missed this wonderful exhibition, where is the best museum now to see Giovanna Garzonis work?

Thankyou

Great question! The museums most likely to have a body of work by Garzoni are in/around Florence: the Uffizi Galleries, and the Museo della Natura Morta at Poggio a Caiano (the latter is apparently temporarily closed). But it would be worth checking before you make a trip to establish whether the works by her that the museums hold are currently on display.