Guest post by Elizabeth Lev, Duquesne in Rome

Caravaggio is now a household name; sometimes it seems that he was the sole artistic genus of the turn of the seventeenth century. As with any superstar player, though, there were dozens of hungry talents nipping at his heels. Guido Reni, Annibale Carracci and young Peter Paul Rubens were his most famous artistic rivals, studying his techniques and hunting the same commissions.

But there is one contender—whose fame, like Caravaggio’s, was international; whose work commanded similar prices; and whose patrons also included princes and prelates—whose name is all too frequently left out of the list. She was Lavinia Fontana, the first professional female painter in Italy, whose stratospheric success story remains to this day insufficiently appreciated.

Introducing Italy’s first professional woman artist

Lavinia was born on August 24, 1552 in Bologna, at the time the second city of the Papal States. Bologna had a history of remarkable woman. In the fourteenth century, Novella D’Andrea had lectured at the University of Bologna—albeit from behind a screen, to hide her beauty. The fifteenth-century artist Caterina Vigri, of the Poor Clares (also known as Saint Catherine of Bologna), was invoked as a patroness of painting. It was a fertile terrior to produce exceptional fruits.

Lavinia was the daughter of Prospero Fontana, an Italian Mannerist artist. He worked with Taddeo Zuccari and Giorgio Vasari, and counted among his patrons Pope Julius III and French sovereigns Henry II and Caterina de Medici. Prospero had two daughters, Emilia and Lavinia, whom he introduced to the family profession. He soon recognized that the pictorial talent lay with Lavinia, his youngest, and he lavished attention on her artistic formation.

An unconventional marriage agreement

In the years before Lavinia came of marriageable age, Prospero’s fortunes had waned. So when it came time to dower Lavinia, he had to get creative. Confident in Lavinia’s talents, he proposed a union between his daughter and the son of successful merchant from Imola, Paolo Zappi, himself an amateur artist. The marriage agreement stipulated that Lavinia’s potential for earning money through her art obviated any requirement for a dowry. Paolo accepted this novel proposal (including the awkward codicil that his father-in-law would live with them) and they were married on February 14, 1577.

Lavinia’s self-portrait, painted on the eve of her marriage, shows an elegant young woman playing the spinet, with an easel placed by the window in the background. She gazes at the viewer with quiet confidence in her talents, both musical and pictorial, as well as in her status.

The marriage was a tremendous success—her career soared, even as she bore 11 children. When she was overwhelmed with work, Paolo helped out as a studio assistant. Her second self-portrait, painted two years later, would privilege her husband’s last name alongside hers.

Lavinia as a portrait artist

Lavinia’s early clientele consisted of wealthy noble women looking for portraits, most often with their lap dogs. Under her father’s tutelage, she had honed her ability to produce excellent likenesses. But Lavinia’s eye also caught the splendor of Bolognese fashions: no gold stitching, lacy flourish, beaded design, or fine jewelry was neglected by her brush. In the same way that the paparazzi zero in on the gowns of movie stars at the Oscars, Lavinia captured the glamour of the most influential women of Bologna.

Her Portrait of a Noblewoman, painted shortly after her marriage, juxtaposes the stiff brocade—embellished in minute detail with pearls, chains and lace—with a playful puppy. With the inclusion of the dog, traditionally a symbol of fidelity in Renaissance art, she balances the status of the sitter with charming and humanizing touch.

Painting for the Church

But greater challenges called. The erudite prelate Cardinal Gabriele Paleotti, Archbishop of Bologna and a leader in Counter-Reformation Italy, took it upon himself to spearhead a call-to-arms of the visual arts. He recruited the best painters to produce works that would both delight and teach the Catholic faith to viewers in post-Reformation Italy. Religious commissions, demanding some kind of theological literacy, had always been the province of men. A few, rare, amateur female painters had made devotional images and pious decoration, but none had ever produced a work that would hang publicly above an altar in a church.

The Cardinal, in whose circles Lavinia’s father moved, took an interest in Prospero Fontana’s talented daughter. In 1584, Lavinia Fontana became the first woman to produce an altarpiece on commission. The Assumption of Ponte Santo, now in the Pinacoteca of Bologna, drew upon Raphael, as well as the innovative ideas of the new Carracci school.

The monumental saints kneeling in the lower section exemplify the expressive monumentality of the Renaissance, while the Virgin is one of the earliest examples of the iconography of the Immaculate Conception. In 1593, Paleotti personally commissioned an Assumption for San Petronio in Bologna, paying a whopping 300 scudi, the same amount the Giustiniani family would pay Caravaggio for his Love Victorious.

New clients, new influences, new subjects to portray

Lavinia made her first trip to Rome in 1586, where her works caught the eye of Spanish Cardinal Francisco Pacheco. Before long, she had commissions for paintings for the King of Spain.

Lavinia’s subject matter changed during her Roman sojourn. Perhaps the shift was due to her absorbing the grandeur of Michelangelo and the ancient monuments. Perhaps it was due to the abundance of female saints honored in Rome’s hundreds of churches. Or perhaps it had to do with the influence of her contemporary Torquato Tasso, the celebrated poet whose book on heroic women had been published three years earlier. Whatever the cause, Lavinia’s works began to feature powerful women, from her stirring Judith with the Head of Holofernes, to the massive Queen of Sheba Meeting Solomon—both heroines noted by Tasso.

Lavinia’s Christ and the Woman at the Well stands out for its iconic representation of the Samaritan woman speaking to Jesus. They occupy the entire canvas: Christ, calm, head resting on his palm, talks to the attractive lady in seductive attire that cinches her waist and reveals her calves. The startled apostles are relegated to the distance, staring as Christ dedicates his attention this second-class citizen of the desert.

The woman, whose intemperate life has just been described by Jesus, is chosen to announce the coming of the Savior to her people. He has picked the least likely vessel to convey the news of salvation. For a woman painting scripture in a city of prelates, this work must have had special resonance. Lavinia’s maiden name, Fontana, means fountain, so perhaps the prominence of the well between the two central figures took on personal meaning.

The Roman years

Jubilee year 1600 saw a record number of pilgrims to the Eternal City. It was the year that launched Caravaggio’s career, and the year that Lavinia attained another first. The Dominican order, which had built a new chapel in honor of St. Hyacinth of Poland (canonized in 1594), commissioned Lavinia to produce the altarpiece. This was a moment of triumph: Lavinia had broken through the bastions of Rome’s artistic boys’ club to leave her mark in one of its oldest and venerated churches.

In 1603, she settled in Rome, where she was inducted into the all-male Academy of St Luke for painters, an honor that eluded Caravaggio. Shortly thereafter, she would produce her largest work, another altarpiece for the Basilica of St Paul Outside the Walls, the site of the tomb of the Apostle to the Gentiles. Tragically, the painting was destroyed along with the basilica during a fire in 1823.

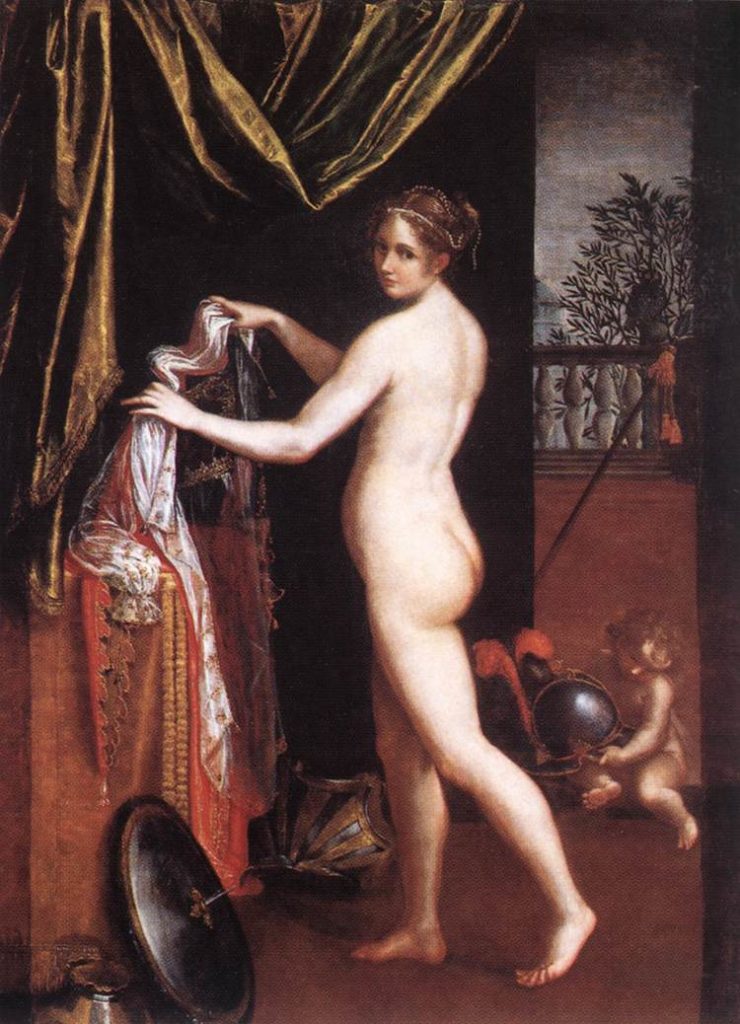

Clearly, Lavinia thrived in the ecclesiastical world. But she also delved into secular subjects, producing images based on classical mythology for private clients. Drawn from Ovid, among other sources, many of the works were erotic in nature, showing her mastery of the nude. For Cardinal Scipione Borghese, nephew to Pope Paul V, art collector extraordinaire and protector of Caravaggio, she painted Minerva Dressing, the first female nude executed by a woman in Italy.

A life well lived

Celebrated and honored, Lavinia died in 1614 and was buried in Santa Maria sopra Minerva, a Dominican basilica. How fitting that this church, built upon a temple and dedicated to the wisdom of women, became the resting place of the woman artist who had it all: fame, family and faith.

Dr. Elizabeth Lev is a Rome-based art historian who teaches Baroque art at Duquesne University’s Italian campus. Her latest book is How Catholic Art Saved the Faith. Visit her website here (www.elizabeth-lev.com).

**

Don’t neglect to visit the Art Herstory Lavinia Fontana resource page!

More Art Herstory blog posts about Italian women artists:

Three Historic Women Artists Exhibitions: A Dispatch from Italy, by Alessandra Masu

Female Solidarity in Paintings of Judith and her Maidservant by Italian Women Artists, by Sivan Maoz

Plautilla Nelli and the Restoration of her Altarpiece Madonna del Rosario. by Jane Adams

Roma Pittrice: Women Artists at Work in Rome Between the Sixteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, by Alessandra Masu

Judith’s Challenge, from Lavinia Fontana to Artemisia Gentileschi, by Alessandra Masu

Stitching for Virtue: Lavinia Fontana, Elisabetta Sirani, and Textiles in Early Modern Bologna, by Dr. Patricia Rocco

Thoughts on By Her Hand, the Hartford Iteration, by Erika Gaffney

Plautilla Bricci: A Painter & “Architettrice” in Seventeenth-century Rome, by Alessandra Masu

The Restoration of Royalty: Lavinia Fontana’s Queen of Sheba and King Solomon, by Dr. Aoife Brady

By Her Hand: Personal Thoughts and Reflections on an Exhibition, by Oliver Tostmann

Sister Eufrasia Burlamacchi (Lucca, 1478–1548), by Dr. Loretta Vandi

Giovanna Garzoni’s Portrait of Zaga Christ (Ṣägga Krǝstos), by Dr. Alexandra Letvin

In defense of monographic exhibitions of female artists: The case of Fede Galizia, by Camille Nouhant

The Ladies of Art are in Milan, by Dr. Cecilia Gamberini

Elisabetta Sirani: Self-Portraits, by Jacqueline Thalmann

Celebrating Bologna’s Women Artists, by Dr. Babette Bohn

Drawings by Bolognese Women Artists at Christ Church, Oxford, by Jacqueline Thalmann

Lavinia Fontana and Elisabetta Sirani at the Smith College Art Museum, by Dr. Danielle Carrabino

Artemisia Gentileschi: What Wasn’t in the London Exhibition and Why it Matters, by Dr. Jesse Locker

Suor Orsola Maddalena Caccia (1596–1676), Convent Artist, Guest post by Dr. Angela Ghirardi

Elisabetta Sirani of Bologna (1638–1665), Guest post by Dr. Adelina Modesti

“Artemisia” at the National Gallery: A Review, Guest post by Dr. Sheila McTighe

“I feel again the violence of a curious desire”: Rare client testimonies on Rosalba Carriera’s erotic art, Guest post by Dr. Angela Oberer

Sister Caterina Vigri (St. Catherine of Bologna) and “Drawing for Devotion”, Guest post by Dr. Kathleen G. Arthur

Plautilla Bricci (1616–1705): A Talented Woman Architect in Baroque Rome, Guest post by Dr. Consuelo Lollobrigida

Two of a Kind: Giovanna Garzoni and Artemisia Gentileschi, Guest post by Dr. Mary D. Garrard

Warp and Weft: Women as Custodians of Jewish Heritage in Italy, Guest post by Dr. Anastazja Buttitta

Rediscovering the Once Visible: Eighteenth-Century Florentine Artist Violante Ferroni, Guest post by Dr. Ann Golob

The Protofeminist Insects of Giovanna Garzoni and Maria Sibylla Merian, Guest post by Prof. Emma Steinkraus

A Tale of Two Women Painters, Guest post / exhibition review by Natasha Moura

Renaissance Women Painting Themselves, Guest post by Dr. Katherine McIver

The Priceless Legacy of Artemisia Gentileschi: A Curator’s Perspective, Guest post by Dr. Judith W. Mann

Trackbacks/Pingbacks