Guest post by Tori Champion, PhD Candidate, University of St. Andrews

It was a mid-winter’s gathering of friends in Paris, late in the year 1756. One of the guests, an erudite antiquarian and amateur artist, found himself startled by what he took to be a living moth, only to realise it was merely a painted one. In response to some playful derision from his host, the painting’s owner, who claimed he was “taken in just like the others,” the man demanded the name of the artist who had so successfully fooled his highly trained eye.

This inquiry was made by Anne-Claude-Philippe de Tubières, the Comte de Caylus (1692–1765), and the deceptive creature was by the hand of a young artist named Marie-Thérèse Reboul (1735–1806). Thus is the anecdote recounted by Reboul’s soon-to-be husband and life partner, fellow painter Joseph-Marie Vien (1716–1809), recalling what he deemed her discovery as an artist from fifty years on as he wrote his memoirs.

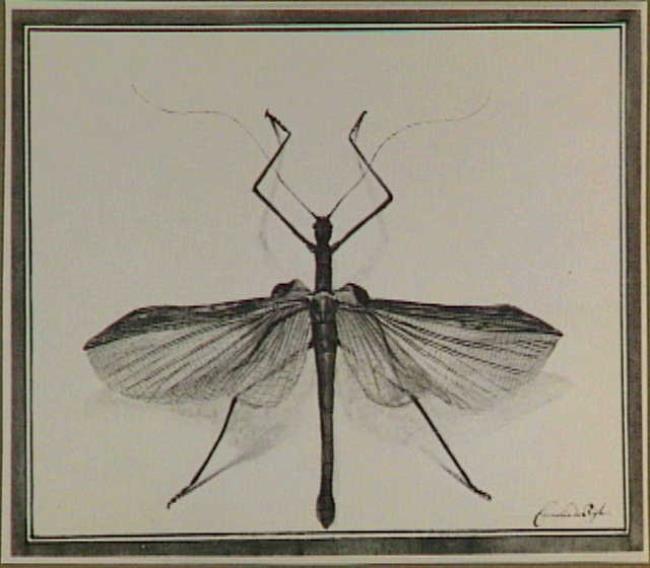

Though the work in question remains untraced, I imagine it to have been akin to one of Cornelia de Rijk’s astonishing insect studies in its trompe l’oeil potential to dupe the viewer. The spindly legs, exceedingly lifelike transparent wings, and faint, masterful articulation of shadow underneath the insect’s body, which seems to enter the space of the viewer, construct an image and enact a visual experience that, as Diderot said of one of Reboul Vien’s later paintings, does the same work as a specimen preserved to be scientifically examined in a collector’s cabinet.

A Vibrant Life Story

To suit Vien’s purposes, the direction of his story quickly veers away from the youthful femme artiste and towards the inevitability of their matrimony. The Comte de Caylus, dually inspired to promote the young lady’s career and end Vien’s prolonged bachelorhood, took it upon himself to play matchmaker between the two artists. The couple were married in the spring of 1757, a few months before Reboul Vien was at age 22 admitted as an académicienne to the French Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture. Over the course of their 49-year marriage, the Viens had three children, one of whom died in infancy, and another who died as a young adult. Their eldest son, Joseph-Marie Vien fils, followed in his parents’ footsteps and himself became a professional artist.

Reboul Vien was one amongst a group of artists who witnessed the end of the ancien régime in France and lived through the tumultuous revolutionary period, working into the early years of the nineteenth century. As such, her biography is rich, nuanced, and complex, but remains understudied. Here I will try only to capture some of the most captivating aspects of her story, and underscore her significant contribution to the history of art.

A Scientific Artist on a Global Scale

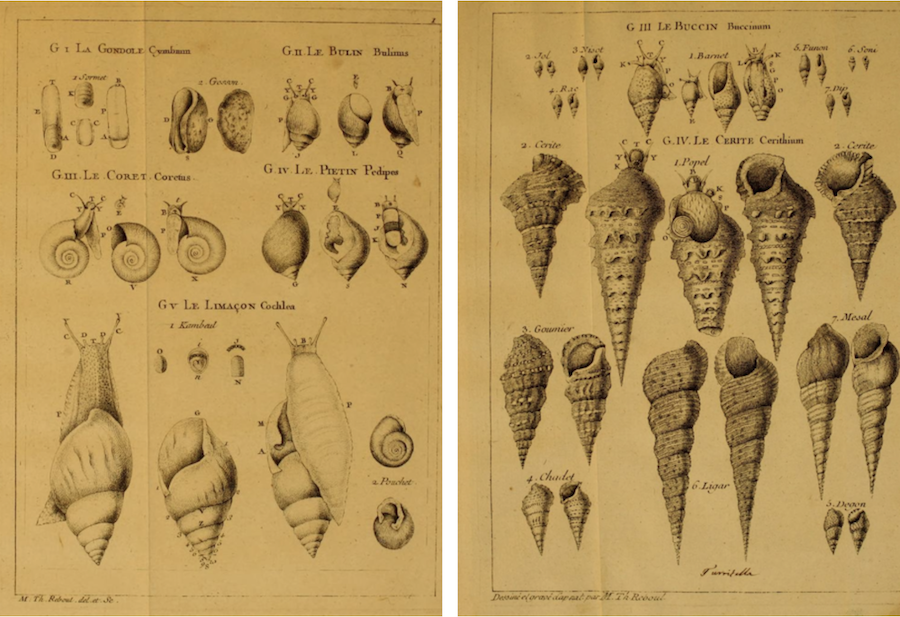

By the time of the encounter narrated by Vien, Marie-Thérèse had already begun working on her first commission as a professional artist. This project was an ambitious series of strikingly fastidious shell illustrations which she drafted and engraved for the leading naturalist Michel Adanson’s 1757 Histoire naturelle du Sénégal, coquillages.

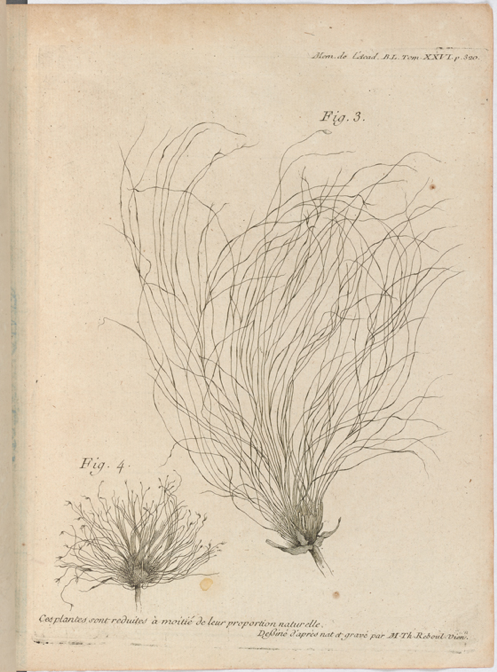

The artist’s name appears at the bottom of each of the nineteen plates, written “M. Th. Reboul.” Some of the drawings were executed d’après nature (from life), in the presence of her shell subjects in the studio, and others were adapted from sketches made in the field. Each shell species is rendered often in two or three views, in some cases with the inclusion of their living inhabitant. The following year Reboul Vien produced illustrations of Sicilian and Madagascan papyrus specimens for Caylus’ Dissertation sur le Papyrus. Her expressive lines imbue even these rather straightforward scientific plant diagrams with a mirthful esprit that is similarly performed in the swirling curves and protruding heads of snails in her shell engravings for Adanson.

Flourishing on the Public Stage

Reboul Vien exhibited work at five out of the six biennial Salons from the years 1757–1767, her subject matter ranging from birds and butterflies to flower and fruit arrangements. Due to their small scale, her entries were displayed on tables at the center of the room with other cabinet pictures and sculptures for up-close examination. With each exhibition she received increasingly more attention in both the Salon programs and critical publications. Diderot’s imaginative responses to her work often act as (fittingly) miniature versions of the ekphrastic tales he was known to spin in front of Salon paintings, particularly large landscapes, before which he was prompted to narrate whole scenes and experiences from a single image. Her 1765 submissions inspired the following words from an ardent critic: “It is remarkable that it is a woman who has extended the limits of this genre, and who has come to give men the example of a more masculine and bold style.”

In Two Pigeons, one of only a few of her paintings to survive, Reboul Vien captures liveliness not only in accurate portrayals of feathers and anatomical pose, but in the glint of each pigeon’s dark, diminutive eyes. It serves as an excellent example of the exactitude Reboul Vien employed to vivify and dynamize her ornithological subjects. Her delicate brushwork carries the weight of scientific precision in her attention to detail and in the reproduction of the birds’ soft, ruffled plumage.

A Fruitful Collaboration

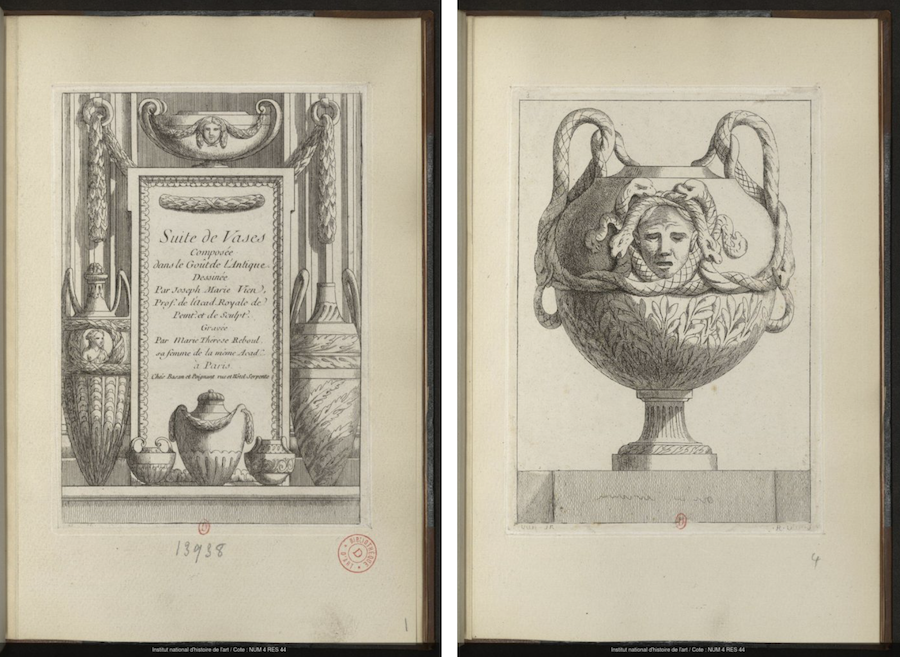

From early on in their relationship Marie-Thérèse and Joseph-Marie engaged in an abundantly collaborative studio practice. In 1760 the duo produced a series of thirteen engravings titled Suite de Vases Composée dans le Goût de l’Antique (Suite of Vases Composed in the Style of Antiquity), which were drafted by Vien and engraved by Reboul Vien.

The asymmetry, rounded forms, swooping garlands, and swirling arabesques of the vases gesture towards mid-century rococo aesthetics. But the emphasis on motifs of classical architecture temple ritual signals both the new directions taken by Vien in his practice and society’s burgeoning interest in antiquity surrounding the recent and ongoing archaeological discoveries at Pompeii and Herculaneum. The Suite, strengthened by Reboul Vien’s confident command of the burin, is intriguing for its reverent and even dark fantasizing upon antique themes.

More than a Muse: Reboul Vien’s Extensive Influence

Reboul Vien served as a model for a number of her husband’s paintings. A portrait completed in 1760, in which the artist-sitter is shown in the act of preparing the materials for a still life, marks an early manifestation of a theme that would continue to reappear in Vien’s oeuvre. Reboul Vien’s head is crowned with a sumptuous silk turban, accented by electric blue feathers and shimmering pearls. The wrapping of fabric, both in the turban and in the shape of the gown, also of silk, in a deep, muted magenta patterned with painterly golden amber flowers, bespeaks a blended influence of the exotic Near East and classical antiquity.

A Turn Towards Antiquity

Previous to the final few years of the 1750s, when he first met Marie-Thérèse, much of Vien’s work was of religious subject matter, with a primary focus on the depiction of the male body, in settings largely denuded and devoid of natural elements. Beginning in the years 1756 and 1757, there is a conspicuous iconographic shift in Vien’s work, which suddenly expands to include expressions of femininity and motifs from both the natural world and antiquity.

Scholars largely agree that Vien’s fascination with the antique came from his mentor Caylus, not to mention the general fervor in mid-century France surrounding the recent and ongoing archeological discoveries. However, I believe that Reboul Vien, in addition to acting as model and muse for Vien’s depiction of classical female figures, may have contributed to the execution of birds and flowers that began to appear in her partner’s canvases.

Marie-Thérèse’s presence is felt most strongly in a series of compositions by Vien from the years 1756–1788. These works depict young women in antique settings and guises, or à la grecque, often accompanied by birds and copious flowers. Starting with Sweet Melancholy, signed and dated in the year of their meeting, we begin to see an infusion of birds and flowers of species and characteristics that abound in Reboul Vien’s work. La Jeune Athénienne, The Sale of Cupids, and A young woman, dressed à la Grecque, holding a canary on her outstretched finger, below, are further examples of Vien’s works that seem to reflect her influence.

The Roman Years…

The Vien family spent the years 1775–1780 in Italy, after Joseph-Marie was named Director of the French Academy in Rome. Whilst there, both artists were honoured with appointments as academicians of the Accademia di San Luca. In his memoirs, Vien recollects the lavish countryside dinner parties attended by himself and Marie-Thérèse. Reboul Vien not only managed the household but oversaw the administration of the Academy when Vien fell gravely ill in the autumn of 1780. On one occasion, when Vien was unable to write, Marie-Thérèse responded to recent correspondence from Paris. The letter, sent to the Comte d’Angiviller on 20 September 1780, is the only known document in her hand. She signed it simply, Reboul-Vien.

…and the Revolutionary Years

In December 1788 the couple’s youngest son died at the age of 23, after he and Marie-Thérèse both caught smallpox. Though she survived, the disease ravaged her body, leaving her with severe scarring, not to mention the indescribable anguish of losing a child for the second time. In the succeeding years, Reboul Vien tended to avoid society because of the disfiguration to her skin, preferring to stay at home or make occasional visits.

The Viens showed sympathy for the French revolutionary movement in its early days. On 7 September 1789, Marie-Thérèse was part of a delegation of wives and daughters of artists who, dressed in white and adorned with the revolutionary cockade, appeared before the National Assembly to offer up their jewelry for the payment of the public debt. The prolonged period of political upheaval brought austerity and hardship, especially after the 1793 closure of the Académie.

A Life-Long Pursuit

A pair of late still lifes, Partridges, Fruits, and Three Bulbs on a Table and Basket of Fruit with Peacock Feathers and Anemones on a Table (1798) testify to Reboul Vien’s maintenance of an active individual artistic practice. With a subtle and subdued colour palette, Reboul Vien displays a connoisseurial eye for the selection of objects, which she arranges, as if in continuation of her early studies of exotic seashells and papyrus in a manner that is equally decorative and conducive to scientific examination. Reboul Vien would live another eight years following the completion of these two works.

New Perspectives on an Extraordinary Career

We must consider the divergent career paths taken by a couple who, at the start of their relationship, were both established professional artists. Between the ages of 22 to 32, Marie-Thérèse produced work commercially, in her own name. She stopped exhibiting publicly shortly after the birth of her third child. While Joseph-Marie rose steadily through the academic ranks across his lifetime, Reboul Vien was denied the possibility of such an ascension. A mystery surrounds a series of correspondence from the late 1760s which suggest that Reboul Vien was a candidate for the position of royal painter of plants, in which she would have succeeded Madeleine Françoise Basseporte. However, for a variety of reasons known and unknown, including competing interests in the successorship from powerful figures at the top of interrelated art and science institutions, this opportunity never came to fruition.

A Trained Portraitist?

Charles-Nicolas Cochin, academician and close personal friend of the Viens, remarked that Reboul Vien could have achieved great success as a portraitist, but dared not out of fear of displeasing the Comte de Caylus, who wished that she only practice natural history painting. This statement not only offers the tantalizing possibility that Reboul Vien possessed some measure of training in the genre of portraiture, but also raises the question as to whether the prospect of her earning a higher income was seen as a threat to propriety. In any case, Reboul Vien’s career and practice was clearly delimited by the demands and caprices of patriarchal societal norms. Having attained academic membership at a young age, Reboul Vien could progress no further professionally, at least not under her own name.

Reboul Vien’s Vital Presence

Restricted as she was to natural history painting in miniature, and likely also to the mediums of watercolour and pastel on paper, it is my supposition that she overcame these stifling limitations by taking on an active role in her husband’s practice. If I am correct in this hypothesis that she acted in the capacity of collaborator, furnishing the natural history elements of Vien’s pictures—as Frans Snyders had done for Peter Paul Rubens in the previous century—she would have found an outlet there for artistic growth, having the freedom to work in oils on large-scale canvases. This line of inquiry, which I hope to pursue further, may serve to provide a partial explanation for Marie-Thérèse Reboul Vien’s abbreviated career as an independently exhibiting artist, and reposition her in a place of prominence within the development of Neoclassicism.

Tori Champion is a PhD Candidate in the School of Art History at the University of St. Andrews. She holds an MA in Art History from the University of Washington and a BS in Public Policy Analysis and International Business from the Kelley School of Business at Indiana University. In the spring of 2021 she served as the Blakemore Intern for Japanese and Korean Art at the Seattle Asian Art Museum. Follow Tori on Instagram.

More Art Herstory posts to do with French women artists:

Blanche Hoschedé-Monet: An Artist in Her Own Right, by Rebekah Hoke Brown

Unpacking the Exhibition: Blanche Hoschedé-Monet in the Light, by Haley S. Pierce

Charlotte Eustache Sophie de Fuligny-Damas, Marquise de Grollier, by David Pullins

Louise Moillon: A pioneering painter of still life, by Lesley Stevenson

Exhibiting Women: The Art of Professionalism in London and Paris, 1760–1830, by Paris Spies-Gans

Marie Laurencin and the Autonomy of Self-Representation, by Mary Creed

The Many Faces of Suzanne Valadon, by Suzanne Singletary

Madeleine Françoise Basseporte’s Hyacinths at the French Court, by Mary Creed

Adélaïde Labille-Guiard: Artist, Friend, Teacher, by Jessica L. Fripp

Marie-Guillemine Benoist, Revolutionary Painter, by Paris Spies-Gans

Seductive Surfaces: Anne Vallayer-Coster’s Vase of Flowers and Conch Shell at the Met, by Kelsey Brosnan

The Theatrical Wonders of Jeanne Paquin’s Belle Époque Parisienne, by Julia Westerman

Victorine Meurent, More than a Model, by novelist Drēma Drudge

Paper Portraits: The Self-Fashioning of Esther Inglis, by Georgianna Ziegler

More Art Herstory posts to do with women natural history illustrators:

Madeleine Françoise Basseporte and the Ribbon as a Signifier of a “Woman’s Touch,” by Tori Champion

Barbara Regina Dietzsch: Enlightened Flower Painter, by Andaleeb Badiee Banta

Books, Blooms, Backer: The Life and Work of Catharina Backer, by Nina Reid

Curiosity and the Caterpillar: Maria Sibylla Merian’s Artistic Entomology, by Dr. Kay Etheridge

Alida Withoos: Creator of beauty and of visual knowledge, by Catherine Powell

Floral Still Life, 1726—A Masterpiece by Rachel Ruysch, by Lawrence W. Nichols

The Protofeminist Insects of Giovanna Garzoni and Maria Sibylla Merian, by Emma Steinkraus

Women in Zoological Art and Illustration, by Ann Sylph, Librarian of the Zoological Society of London

More Art Herstory posts to do with 18th-century women artists:

Mary Linwood’s Balancing Act, by Heidi A. Strobel

A Short Reintroduction to the Life of Anna Dorothea Therbusch (1721–1782), by Christina K. Lindeman

Rosalba Carriera at The Frick Collection, by Xavier F. Salomon

Angelica Kauffmann: Grace and Strength, by Anita V. Sganzerla

“I feel again the violence of a curious desire”: Rare client testimonies on Rosalba Carriera’s erotic art, by Angela Oberer

Rediscovering the Once Visible: Eighteenth-Century Florentine Artist Violante Ferroni, by Ann Golob