Guest post by Alessandra Masu, author, journalist and art historian

Following the pioneering studies of Consuelo Lollobrigida, which culminated in the first monograph on Plautilla Bricci. Pictura et Architectura Celebris. The architect of the Roman Baroque, the first solo show dedicated to the first professional female architect in Italy (and perhaps in Europe) has just been inaugurated at Palazzo Corsini in: Plautilla Bricci painter and architect. A silent revolution. It is an exhibition that sums up several firsts, even more necessary given that the artist had already been brought to the attention of the general public in the fictionalized biography of Melania Mazzucco (L’architettrice), and that Plautilla Bricci (Rome, 13 August 1616–post 6 September 1690), and Roman women artists in general, were under-represented (and also, frankly, misrepresented, as in the case of Claudia del Bufalo) in the recent anthological show Le Signore dell’Arte/The Ladies of Art in Milan.

Portraits and Self Portraits

In a newly renovated Galleria Corsini with a wi-fi network, an app to support the visit, and new lighting, the exhibition, curated by Yuri Primarosa, brings together for the first time the entire graphic and pictorial production of the artist, with a section on her unfortunately now demolished architectural masterpiece: Villa Benedetta-Il Vascello. In the entrance hall, a “wall of the talented women” (a reinterpretation of the concept of the Room of the Beauties?) juxtaposes the Portrait (or Self-portrait) of Faustina Maratta (Corsini) and the Self–portrait of Artemisia Gentileschi from Palazzo Barberini to the Girl with a Compass (an Allegory of Architecture or Astronomy) of the Spada Gallery, already on the cover of Mazzucco’s book, with Portrait of an architect, likely an effigy of Bricci, from a Californian private collection. In the picture below, the identification of the sitter as Plautilla was proposed in recently by Clovis Whitfield, and the attribution of the painting to Antonio Gherardi was proposed by Francesco Petrucci.

Artist active in Rome, mid-17th century, Portrait of an architecturess (Plautilla Bricci?), oil on canvas, 66.1 x 52.7 cm. Private collection, Los Angeles.

An artistic family

Like almost all of her woman artist colleagues, Plautilla was the daughter of an artist. In the workshop of her father Giovanni (son of a Ligurian mattress-junk dealer who emigrated to Rome in the 1560s) she acquired much more than the rudiments of drawing and colouring. In addition to being a painter from the circle of Arpino, Giovanni Bricci was also a polygraph and poet, actor and comedian, musician and composer. Plautilla’s mother, Chiara Recupiti, of Neapolitan origins, may have been a relative of Ippolita, the virtuous singer in the service of Cardinal Montalto.

Like Orazio Gentileschi for Artemisia, Giovanni not only provided his daughter’s apprenticeship but also created her first network of contacts and professional opportunities.

Plautilla’s debut: The miraculous icon of Santa Maria in Montesanto

He must have directed Plautilla’s debut with the Madonna and Child of Santa Maria in Montesanto (1640 ca.). While Orazio chose to promote Artemisia as a “miracle in painting,” Bricci launches Plautilla as a miracle of virtue: on the back of the canvas the signature of the young artist (“depicted about the year 1640 by Plautilla Bricci a Roman spinster”) is accompanied by the report of a prodigious event: the work had been finished by the Madonna herself! This debut guaranteed her a favorable position in the mass production industry of devotional images and must have attracted the attention of the man who was to become her mentor and main patron: Abbot Elpidio Benedetti.

Plautilla Bricci and Elpidio Benedetti: a story of parallel lives

Elpidio was the son of the Bolognese Lucia Paltrinieri and Andrea, an embroiderer native of Poggio Mirteto whose “paonazza” planet and the corporal bag (1622), donated by Gregorio XV Boncompagni to the Bolognese archdiocese he had held for nine years before rising to the papal throne, are included in the exhibition. Andrea Benedetti also led a parallel life as an art dealer in his workshop in Banchi in the Ponte district, dealing with works by the most sought-after names of the moment: from Guido Reni to Rutilio Manetti.

Like Plautilla, Elpidio grew up in his father’s workshop attended by artists, intellectuals and clients. Elpidio became an amateur artist, in close relationship with masters such as Gian Lorenzo Bernini (his terracotta bust of Pope Alexander VII is in the show), Pietro da Cortona, Andrea Sacchi, Giovan Francesco Grimaldi and Giovan Francesco Romanelli, author of the Madonna del Rosario for the church of Santi Domenico e Sisto in Rome, restored for the occasion in the laboratory of the National Galleries. But Elpidio aspired to an ecclesiastical-diplomatic career, first serving Cardinal Giulio Mazzarino (evoked in the exhibition by a powerful Portrait of Cardinal Giulio Mazarino, attributed to Pietro da Cortona), and later Jean-Baptiste Colbert, as an agent of Louis XIV in Rome, thus becoming a key figure in the political and artistic dialogue between Paris and the Holy See.

Plautilla instead devoted her entire life to art, never marrying and living first with her family and that of her sister Albina, then (from 1678 certainly to 1690) with her brother and collaborator Basilio in the house opposite the church of St. Francesco a Ripa which the abbot had granted her the usufruct for life. The partnership with Benedetti was decisive for Plautilla who, thanks to his support, was able to engage in public works of great prestige and visibility. An example of such work is the chapel and the altarpiece of St. Louis IX in the Chiesa di San Luigi dei Francesi (the church of the French Nation in Rome) (1676–1680)—work financed by the abbot. She also had a hand in the design of monuments and urban interventions conceived by Benedetti. Since the projects are signed by Benedetti, the idea proposed by the curator is that Benedetti invented the concepts and Plautilla drew up the designs. See how in the altarpiece of San Luigi she underlines the fact that she “owns” both the invention and the execution of the painting (cenotaph of Cardinal Mazarin, 1657; staircase of Trinità dei Monti) and in the construction of complex buildings such as the villa of delights on the Janiculum, brainchild and spiritual testament of Benedetti.

Plautilla the Painter

To claim the full “motherhood” of the most important of her paintings Plautilla signs the altarpiece of the Holy King of France, not with a simple “fecit,” but with “IN [ VENIT].” And she signs the lunette with the Presentation of the Sacred Heart of Jesus to the Eternal Father (1669–1674) for the Lateran, today in the Vatican, with the formula “invenit et pinxit.”

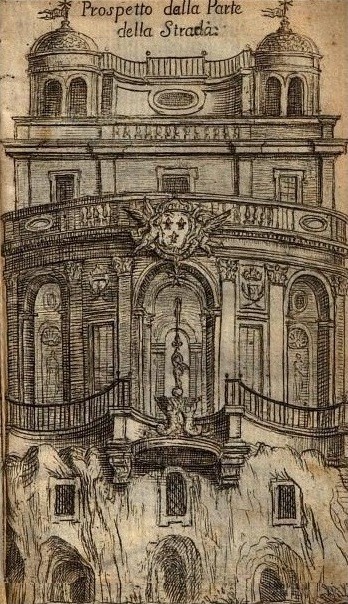

Plautilla the Architectress: Villa Benedetta—The “Ship” Villa

In 1662–1663 work began on her most ambitious and famous creation, the Villa Benedetta outside Porta San Pancrazio. Known as “il Vascello” from the mid-eighteenth century for its visionary facade towards the city in the shape of a ship stranded on the rocks, it was destroyed in 1849 during the French assaults against the Roman Republic. Artists of the caliber of Bernini and Cortona took part in that construction site, but it was Plautilla who directed the workers. This “silent revolution,” as the subtitle of the exhibition says, was made possible mainly by working with and for Benedetti, her enlightened patron.

The abbot evidently intended to import into the papal city that openness to female talent that had determined the success in France of Italian artists of the most diverse disciplines: from the actress, writer and poet Isabella Andreini to Virginia da Vezzo Vouet, appreciated painter at the court of Louis XIII and Anna of Austria.

In the specific field of architecture, the first ladies Jacquette de Montbron (1542–1598), in the service of Caterina de’ Medici from 1587, and Margherita of Austria (1522–1586), wife of Ottavio Farnese, Duke of Parma and Piacenza, the Madama of the homonymous Roman palace, were ladies of the high nobility who mainly engaged in building projects in their possessions. Montbron introduced the model of the Italian villa in Périgord. Margherita of Austria provided the architect Francesco Paciotto with the plans for the Palazzo Farnese in Piacenza, which was then completely redesigned by Vignola. This tradition of first ladies “architectress” was thus shared between France and Italy.

If, as a painter, Plautilla’s trajectory goes from the hyper-archaizing (even acheropita) icon of Santa Maria in Montesanto to the pre-Maratta classicism of the altarpiece of St. Luigi, as an architect active in Baroque Rome, she could only absorb Bernini’s idea of “The Grand Theater of the World.” It inspired both her scenographic stucco drape at the entrance of the chapel of San Luigi, and the elaboration of the first plans for the Villa (1663, preserved in the State Archives of Rome) into the Plan for the main floor (piano nobile) in a private collection (published by Carla Benocci in 2018 but exhibited for the first time at Palazzo Corsini), following the abbot’s trip to France in 1664.

On that occasion Benedetti was presented with the tricky task of acting as an intermediary between Colbert, who had launched the competition for the new Louvre, and the Italian artists invited to the competition, starting with Bernini. In the complex Louvre affair, Benedetti explicitly supported Bernini, consolidating a bond that was convenient for both: for Benedetti, who in that year reached the highest of esteem at the French court and therefore of his career, and for Bernini, animated by the usual determination to excel in competition with his fellow artists. Yet the model of the villa is French, precisely the Vaux-Le-Vicomte mansion designed by André Le Notre for the minister Nicolas Fouquet. Benedetti visited it in 1664, and was so fascinated by it that he sent a drawing to Rome to suggest how to modify the initial project of his villa after his return to Rome.

Plautilla Bricci: a woman artist disputed between Art History and Gender Studies

The archival research on Plautilla and her circle, the additions to the artist’s catalog set by Lollobrigida, the investigations into the personalities of Giovanni Bricci (in the essays by Riccardo Gandolfi and Maria Barbara Guerrieri Borsoi) and Andrea Benedetti (Magda Tassinari), and the restoration of several paintings (including the Banner of the Compagnia della Misericordia of Poggio Mirteto; see the paintings above and below), and the architectural projects of the State Archives of Rome, all contribute to the reconstruction of the salient features of a quietly revolutionary artist figure, and therefore different and alternative to a star made of Caravaggesque lights and shadows such as Artemisia Gentileschi.

The curators of the exhibition seem to have made a methodological choice and, I would say, the cultural choice, of not wanting to integrate art history with the most up-to-date research by “gender studies” international specialists. (I am thinking for example of the work that Simona Feci and Benedetta Borello have been carrying out for years on the legal status of women and female relationships inside and outside the family in modern Rome, or the contributions of the architectural historian Nicoletta Marconi on the presence of women in the construction sites of Rome and its province between the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.)

This leaves open questions—and answers—on crucial issues such as the very definition of “architectress” in the European context (particularly regarding semi-professional first lady architectresses in England such as Lady Anne Clifford and Lady Elizabeth Wilbraham); on working conditions and labor market for female artists in Baroque Rome; and on relationships between female artists, intellectuals and patrons who—in the exhibition in question—are only mentioned in the catalog in connection to a few female portraits and the collaboration of a fellow woman artist enrolled in the Academy of San Luca, the illustrator Teresa del Po, with the Roman publisher Francesco Tizzoni, sponsored by Plautilla and her brother Basilio.

Una rivoluzione silenziosa. Plautilla Bricci pittrice e architettrice is on at Rome’s Galleria Corsini through April 19, 2022.

Author, journalist and art historian Alessandra Masu loves to unearth the stories of overlooked women and collects art created by women from the sixteenth to the twenty-first century. Alessandra’s writing has appeared in many places in print including D, la Repubblica’s weekly style magazine. As an art historian, she has contributed to several exhibitions and art publications and is the author of the historical novel Lena, che è donna di Caravaggio (EtGraphiae, 2013). In 2020, with Ginevra Bentivoglio Editoria, Alessandra published Perchè io non voglio star più a questa vita. La voce di Beatrice Cenci dai documenti conservati negli archivi romani. In 2016 Alessandra, in collaboration with art historians Consuelo Lollobrigida and Beatrice De Ruggieri, founded the cultural association “Artemisia Gentileschi,” which is based in Rome.

More Art Herstory posts about Plautilla Bricci:

Plautilla Bricci (1616–1705): A Talented Woman Architect in Baroque Rome, by Dr. Consuelo Lollobrigida

More Art Herstory exhibition reviews:

Roma Pittrice: Women Artists at Work in Rome Between the Sixteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, by Alessandra Masu

Early Modern European Women Artists at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, by Erika Gaffney

Carlotta Gargalli 1788–1840: “The Elisabetta Sirani of the Day,” by Alessandra Masu

Sofonisba Anguissola in Holland, an Exhibition Review, by Erika Gaffney with Cara Verona Viglucci

Rosa Bonheur—Practice Makes Perfect, by Ien G.M. van der Pol

Judith’s Challenge, from Lavinia Fontana to Artemisia Gentileschi, by Alessandra Masu

Thérèse Schwartze (1851–1918), by Ien G.M. van der Pol

Anna Dorothea Therbusch: A Woman Painting Against Eighteenth-century Odds, by Stephanie Pearson

Thoughts on By Her Hand, the Hartford Iteration, by Erika Gaffney

The Many Faces of Suzanne Valadon, by Dr. Suzanne Singletary

A Tale of Two Women Painters, Guest post / exhibition review by Natasha Moura

In defense of monographic exhibitions of female artists: The case of Fede Galizia, by Camille Nouhant

The Ladies of Art are in Milan, by Cecilia Gamberini

“Artemisia” at the National Gallery: A Review, by Sheila McTighe

Artemisia Gentileschi: What Wasn’t in the London Exhibition and Why it Matters, by Jesse Locker

“La grandezza del universo” nell’arte di Giovanna Garzoni / “The grandeur of the universe” in the art of Giovanna Garzoni, by Sara Matthews-Grieco

By Her Hand: Personal Thoughts and Reflections on an Exhibition, by Oliver Tostmann

Thoughts on Feminist Art History in the Wake of Artemisia: Vrouw & Macht at Rijksmuseum Twenthe, by Jitske Jasperse

More Art Herstory posts about Italian women artists:

A Home for Women Artists in Rome, by Alessandra Masu

Female Solidarity in Paintings of Judith and her Maidservant by Italian Women Artists, by Sivan Maoz

Plautilla Nelli and the Restoration of her Altarpiece Madonna del Rosario. by Jane Adams

Lavinia Fontana and Elisabetta Sirani at the Smith College Art Museum, by Dr. Danielle Carrabino

Lavinia Fontana: Italy’s First Female Professional Artist, Guest post by Dr. Elizabeth Lev

Renaissance Women Painting Themselves, Guest post by Dr. Katherine McIver

Sister Eufrasia Burlamacchi (Lucca, 1478–1548), by Dr. Loretta Vandi

Giovanna Garzoni’s Portrait of Zaga Christ (Ṣägga Krǝstos), by Dr. Alexandra Letvin

Sister Caterina Vigri (St. Catherine of Bologna) and “Drawing for Devotion,” Guest post by Dr. Kathleen G. Arthur

Two of a Kind: Giovanna Garzoni and Artemisia Gentileschi, by Dr. Mary D. Garrard

The Protofeminist Insects of Giovanna Garzoni and Maria Sibylla Merian, by Dr. Emma Steinkraus

The Priceless Legacy of Artemisia Gentileschi: A Curator’s Perspective, by Dr. Judith W. Mann

Thanks for finally talking about > The Silent Revolution of

Plautilla Bricci | Artist & Architect of C17th Rome < Loved it!

I’m sorry I missed this.